The recent near-collision of a PLA Navy tank landing ship and the missile-guided cruiser USS Cowpens in the South China Sea represents yet another incident in a long line of instances of Chinese gamesmanship with the US Navy extending back to the March 2009 harassment of the USNS Impeccable and the 2001 downing of an EP-3. In each of these cases, the Chinese took issue with the United State conducting surveillance of Chinese military targets at sea or on the Chinese mainland (in this case, the Cowpens was conducting surveillance of the PLAN aircraft carrier Liaoning, which was for the first time conducting exercises in the South China Sea).

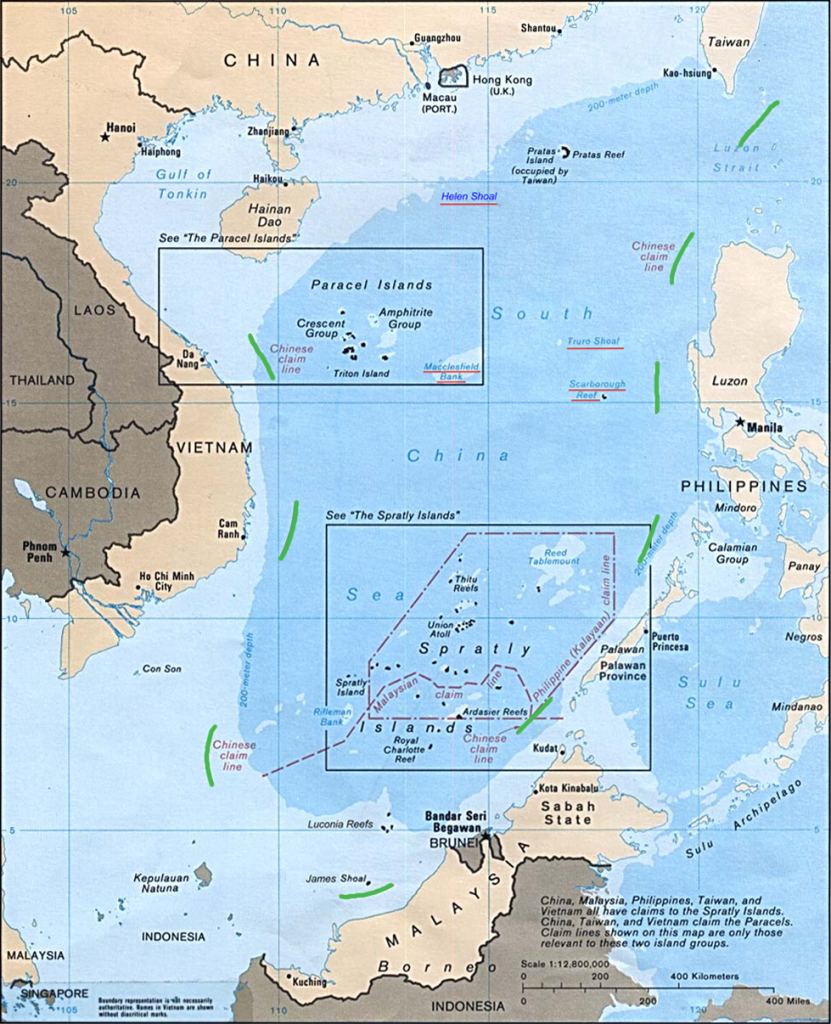

All three occurred in the South China Sea, although it is not currently clear from media reports where exactly the most recent confrontation took place. This could prove to be an important distinction. Previously, Beijing justified its escalatory responses to US actions by saying that they interpreted U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to mean that military activities within the Chinese exclusive economic zone (EEZ) were prohibited without the consent of China. The EP-3 and Impeccable incidents both occurred near Hainan Island, inside the Chinese EEZ. If this most recent escalatory move occurred outside the EEZ, it will be particularly interesting to see how China justifies itself. Are they expanding their legal interpretation further by claiming that all military activities conducted in waters within the so-called “nine-dash line” must receive Chinese approval? This of course is conjecture—especially given that as of this writing it also appears from a cursory glance of Chinese-language news websites that neither the PLA nor the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has yet made a statement. At that point this issue will require the analysis of individuals better trained in the vagaries of Chinese territorial legal disputes than I.

Also pertinent to this debate is the recent admission at this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue (by a Chinese military officer no less!) that the PLAN was itself already conducting surveillance of U.S. military installations on Guam and Hawaii within U.S. EEZs around those islands. As Rory Medcalf points out, this clearly contradicts the Chinese legal position on the matter. At what point will this hypocrisy actually catch up with the PLA and necessitate a change in China’s legal position?

Last week at an event at the Wilson Center, Oriana Skylar Mastro suggested that China’s recent announcement of the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) fits into a pattern of Chinese “coercive diplomacy,” in which China manipulates risk and intentionally raises the risk of an accident, a view echoed by other analysts in an approach known as salami tactics. In this way, China stops just short of further escalation, and achieves its objectives of slowly chipping away at opposing territorial positions and international legal norms. This analysis is clearly simpatico with her earlier published work regarding the Impeccable incident and the most recent confrontation involving the USS Cowpens. In her paper, Dr. Mastro identified a coordinated Chinese media campaign and legal challenge that accompanied the PLA’s military provocation. She also recommended that in order to prevent further Chinese attempts at escalation, the United States should publicize these events, directly challenge the Chinese legal position, and maintain a strong presence in the area, all things which the United States is now doing (specifically in the Cowpens case, the Department of Defense broke the story).

These are sound responses to Chinese attempts to delegitimize lawful operations in international waters. What should the United States not do? In an article published by the Washington Free Beacon, Bill Gertz quotes a senior fellow at the International Assessment and Strategy Center, Rick Fisher, who suggests that China in this incident is intentionally “looking for a fight” that will “cow the Americans,” and that the United States and Japan should heavily fortify the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in response. Aside from the fact that China certainly is not “looking for a fight,” fortifying the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands would be a terrible idea. The U.S. government does not even take an official position on the islands’ sovereignty! The U.S. response should certainly be firm in insisting that surveillance within foreign EEZs is completely legitimate and lawful; but turning this issue into about something other than surveillance in international waters would be blowing it out of all proportion. The United States should, in contrast to the ways in which China’s behavior is perceived, proceed carefully but resolutely and stick to its guns.

William Yale is a graduate student at Johns Hopkins SAIS. He has lived in China for two years, and worked at the Naval War College and the U.S. State Department. He tweets @wayale and blogs at williamyale.com.