By Lieutenant Commander Michael S. Silver, USN, and Lieutenant Commander James J. Moore, USN

With contributions from Lieutenant Commander Loren M. Jacobi, USN, and Lieutenant Robert J. Dalton, USN

Introduction

The future of the Helicopter Sea Combat Community (HSC) community is at risk. HSC, which is made up of both carrier air wing (CVW) and expeditionary (EXP)squadrons that employ MH60S helicopters, struggles with its purpose to the fleet. Platform capabilities fail to keep pace with technological advancements and HSC warfighting relevancy is diminishing. A focused vision, careful risk mitigation, rebalanced mission priorities, and thoughtful platform acquisitions are needed in order to strengthen the fleet and secure the future of the HSC community.

What Does an HSC Vision for 2026 Look Like?

What is needed is will—the fortitude to recognize that we have to change the way we currently operate. –VADM Thomas Rowden, “Distributed Lethality.”1

The HSC community of 2026 has a renewed focus on maritime employment and a customer-focused concept of operations based on the needs of warfare commanders. This means pivoting to become the maritime mission experts, integrating into a Carrier Strike Group (CSG), Amphibious Ready Group (ARG), or Independent Deployer via the Distributed Lethality (DL) model:

“Distributed lethality is the condition gained by increasing the offensive power of individual components of the surface force (cruisers, destroyers, littoral combat ships [LCSs], amphibious ships, and logistics ships) and then employing them in dispersed offensive formations.”2

A pivot to distributed lethality requires alignment with warfighting requirements, focused funding along a revised community Roadmap/Flight Plan, and leveraging of existing naval aviation programs of record. The Mid-Life Upgrade (MLU) is a Naval Aviation Enterprise requirement that reviews and improves resources throughout the lifespan of platforms. The forthcoming MH-60S MLU presents a watershed opportunity for the HSC community. It offers the clearest path to match capabilities with warfighting requirements outlined in the CNO’s Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority while meeting the demands of an environment increasingly shaped by the need for network-enabled technology in constrained budgets.3 Assuming the current Service Life Extension Plan (SLEP) will deliver the first MH-60S in 2028, the MLU opportunities for warfighting upgrades, guided by HSC Roadmaps and aligned with a maritime pivot to DL, will enable the HSC community to provide warfare commanders with the capabilities they require to meet future maritime security challenges.

President Trump is calling for more ships in the Fleet and the Navy’s revised force structure assessment will likely drive an increase in demand for MH-60S missions. Now is the time for the HSC community to make the most of the MLU in order to recast itself in the mold of DL. Doing so will create a future comprised of more powerful, networked platforms combined with innovative tactics that enhance naval warfare capability and support developing requirements generated from national strategy.

Limiting Risk

HSC has assumed an injurious level of risk training to a broad range of specialized warfare competencies. The battle to maintain currency and proficiency in specialized overland missions has increased risk, resulted in mishaps, and has made warfare commanders reluctant to rely on the HSC community for overland personnel recovery (PR), special operations forces (SOF) missions, and direct action (DA) missions. Historical HSC community data reveals that over 50 percent of HSC mishaps occurred during controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), with the majority occurring during training in a degraded visual environment (DVE) or executing unprepared landings (UPLs), resulting in four Class A mishaps, three Class B mishaps, 22 Class C mishaps, and one Class D mishap.4

Compounding this data, the HSC community has relied on Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Instructors (SWTIs) as subject matter experts to teach the most challenging missions, but SWTIs have struggled to maintain minimum flight hour requirements themselves.5 The CNO’s direction to “guide our behaviors and investments, both this year and in the years to come” demands that the community’s plan for the future adheres to responsible risk/benefit analysis. To do so, the HSC community should consider tailoring Defense Readiness Reporting System-Navy (DRRS-N) requirements to focus on maritime missions that contribute to a DL model.6

Rebalancing Mission Priorities

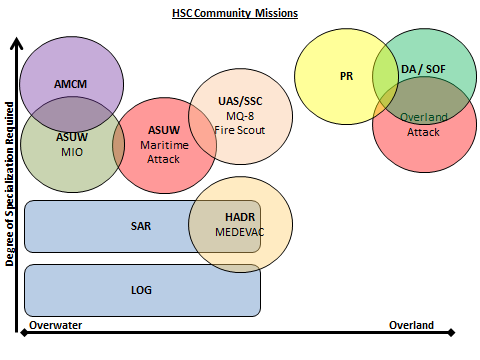

Fleet Carrier Air Wing HSC Squadrons maintain 10 primary mission areas and four secondary mission areas encompassing 210 required operational capabilities.7 A visual depiction of HSC missions can be seen in the figure below.

Given constrained resources, the number of specialized mission areas (seen at the top of the figure) is inversely proportional to the ability to perform those missions well. When considering where to allocate future resources, the HSC community must prioritize the maritime domain. The current MH-60S, which makes up 275 of the 555 aircraft in the Navy’s MH-60R/S inventory, lacks adequate sensors, sensor integration, and long-range weapons systems that warfare commanders require. As a result, decision makers mainly rely on the MH-60R to perform anti-surface warfare (ASUW) and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) missions focused on maritime dominance. The HSC community must obtain the systems that warfare commanders desire and focus training on the missions that utilize them.

According to the Master Aviation Plan (MAP), there will be an increase in HSC employment as more LCS enter the fleet. This will be a major driver for requirements and is consistent with the DL concept. Since USN units are expected to be lethal against a broad range of threats, the HSC community must use existing opportunities to ensure that MH-60S integrated sensors are absolute requirements in order to provide situational awareness for warfare commanders, augment networked targeting platforms, and become a relevant sea control platform.

“The more capable platforms the adversary has to account for, the more thinly distributed his surveillance assets will be and the more diluted will his attack densities become. The more distributed our combat power becomes, the more targets we hold at risk and the higher the costs of defense to the adversary.”8

Rebalanced HSC mission sets should prioritize SAR/LOG/HADR, AMCM, UAS & SSC, and ASUW, while carefully tailoring overland PR/SOF DRRS-N requirements.

SAR/LOG/HADR. Warfare commanders have historically demanded force-enabling mission sets from the rotary wing community and they will continue to be necessary core competencies operating aboard any surface platform. In addition to supporting daily operations, the HSC community has made significant strategic contributions executing SAR/LOG/HADR mission sets in times of crisis (e.g. tsunami relief operations, non-combatant evacuation operations, etc.). With the Trump administration demanding an increase in fleet size and publicly supporting a 350 ship Navy, it is logical to assume that there will be additional demand for force-enabling missions that require rotary support. The MH-60S is the platform of choice to meet increased demand for these mission sets and the HSC community should position itself accordingly.

AMCM. According to the Naval Aviation Vision 2016-2025, “effective mine warfare is a key tenet of the Navy’s anti-access/area-denial (A2AD) strategy, and AMCM plays an important role in executing that strategy,” yet the HSC community has fundamentally marginalized and underdeveloped this important capability.9 Already a Navy program of record, focusing on AMCM will address a significant challenge to U.S. maritime superiority. The MH-53E brings significant capability to heavy-lift contingency logistics requirements, while being a proven AMCM platform. With several MH-60S AMCM systems failing to meet requirements, a heavy lift replacement like the MH-53K would provide a baseline for LOG and AMCM missions. The MH-60S and unmanned HSC platforms like Fire Scout need to augment AMCM capabilities as soon as possible in order to counter this powerful asymmetric threat and contribute to the success of DL.

UAS & SSC. HSC is the first Naval Aviation community to significantly develop and integrate unmanned systems, which purports to be a force multiplier in DL operations. Becoming UAS experts positions the HSC community to become leaders in the SSC mission, providing greater range, sensor capability, and distributed lethality than manned rotary-wing assets, while simultaneously reducing human risk, cost, and impact to routine events such as CVN cyclic operations. Currently, UAS is a secondary requirement on FRS and Expeditionary squadrons. Flight crews and maintainers are required to maintain separate currency and qualification on diverse platforms. Unmanned systems are integral to the future of warfare and the HSC community should explore resourcing commands and crews that are devoted to unmanned platforms.

ASUW. Whether operating as part of a CSG, ARG, or Independent Deployers; offensive and defensive anti-surface capabilities offer warfare commanders a wide range of options while simultaneously adding complexity to the calculus of potential maritime adversaries. An HSC DL model can protect a high value unit (HVU), hold enemies at risk at range with a wide variety of unguided or precision guided munitions, and employ the MH-60S in conjunction with the MH-60R when required, all in the interest of defending Sea Lines of Communication and ensuring maritime security and superiority.

PR/SOF. Despite an increased focus on overwater missions, overland mission capability must still exist organically within the Navy Rotary Wing community. Overland capability must be maintained in a resource-constrained environment while implementing ways to mitigate risk. This could be accomplished by carefully tailoring training requirements for specific AORs beyond the current HSC Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Program 3502.6. Commands that are not projected to operate overland while deployed should be expected and even encouraged to report “yellow” or “red” in DRRS-N, reducing the risk associated with specialized overland mission sets and freeing up resources for other mission areas. This will permit the HSC community to “demonstrate predictable excellence in the execution of our maritime missions” and increase tactical relevance by seeking missions that are desired by warfare commanders.

While accepting some risk in the overland power-projection/PR missions, the HSC community needs to link squadrons to relevant NSW and other SOF units to be the customer of choice when doing SOF missions in the maritime domain. Missions should be trained to and executed on a sound risk/reward level to give SOF the reach needed to execute their effects from traditional and non-traditional surface platforms. A ship takedown executed from a Military Sealift Command (MSC) ship or LCS may be an emerging counter terrorism requirement in the globalized threat domain.

Technology/Acquisitions Recommendations

DoN budget challenges (Columbia-class SSBN, shipbuilding, TACAIR Inventory Management, etc.) will continue to pressure naval rotary wing funding. The MH-60 Service Life Assessment Plan (SLAP), beginning in FY17 and transitioning into SLEP in the early 2020s, provides a unique opportunity to incorporate key mission upgrades and capabilities in conjunction with MH-60 MLU. While MLU is still unfunded and currently outside the Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP), the HSC community should work with OPNAV N98 and the Naval Aviation Enterprise (NAE) to support upgraded MH-60S capabilities that enhance Fleet DL.

Obtain RADAR capability. The HSC community is the aviation asset for LCS, but it has virtually no networked sensor capability. In a distributed threat environment, the MH-60S needs to be able to contribute additional sensor information to decision makers and shooters. The logical solution is a phased planar array RADAR, which gives HSC the ability to positive hostile identify (PHID) at range and use RADAR designation for the Joint Air to Ground Missile (JAGM). An LCS based SAG needs air-based sensor coverage, all-weather PHID capability, and the ability to hold the enemy at risk, at range. JAGM Block III (another Navy program of record), will virtually double the range of the HELLFIRE missile. Due to limitations of the current MH-60S MTS sensor at long ranges in humid overwater environments, the HSC community will face significant limitations in utilizing JAGM at ranges beyond legacy HELLFIRE capabilities. The MH-60R, with RADAR-based designation capability will be able to utilize the full range envelope of JAGM. Until this gap is bridged, only the 280 MH-60R helicopters out of the Navy’s 555 MH-60R/S inventory will be able to leverage the full capability of this weapon. Obtaining RADAR imaging and designation will enable the MH-60S to integrate into the overwater joint fires world of DL.

Approve the MH-60S “Torpedo Truck” concept for the Pacific Fleet. The “Torpedo Truck” concept multiplies warfighting effectiveness for any battle group by permitting HSC platforms to carry torpedoes that can be employed in conjunction with an MH-60R. Time on station is primarily determined by fuel load and aircraft weight limitations necessitate a choice of either additional fuel or expendables such as torpedoes. Outfitting an MH-60S “shooter” platform with torpedoes permits an MH-60R platform to take off with more fuel (instead of torpedoes) and remain on-station as the “designator” for longer periods of time. The MH-60S “Torpedo Truck” significantly increases ASW warfighting capability (particularly on LCS) and enhances DL. Additionally, to bring ASW capability to a broad range of Independent Deployers, the “Torpedo Truck” directly supports DL requirements. No matter what the ASW threat, a threat submarine needs to be close in to launch a torpedo against a ship. The DL concept applied to ASW in a non-traditional LCS SAG is only possible with the ability to employ organic weapons that can hold the enemy at risk, at range. The “Torpedo Truck” concept has already been endorsed by Carrier Air Wing FIVE (CVW 5) and requires further review from higher Pacific Fleet echelons. Commander DESRON 15, Commander NAWDC, Commander CTF 70, and Commander SEVENTH Fleet should consider generating an urgent operational needs statement based on current and projected submarine threats, and work with OPNAV for immediate approval.11

Obtain Ku-band HAWKLINK capability. The HSC community needs to connect HAWKLINK to warfighting requirements as they are currently written. HAWKLINK permits full motion multi-spectral targeting sensor (MTS) video feeds that are demanded by warfare commanders who desire real-time evaluation of potential ASUW threats. Additionally, the “Torpedo Truck” concept could drive the ASW requirement for HAWKLINK (in SEVENTH Fleet in particular). It is not possible to have pervasive, wide-area sensor coverage over the entire Pacific. It is possible, however, to use distributed sensors to localize threats in the form of ship-based towed arrays, submarine-based networking, and P-8 buoy brickwork. Having HSC detachment-based, LCS-organic capability to launch weapons allows networked sensor systems to continue search and localization without coming off-station to launch a weapon for both ASUW and ASW missions.

Procure MH-53K Heavy-Lift and AMCM capabilities. CSG logistics requirements are immense when operating continuous flight operations, particularly during a contingency that prevents or delays pulling into port. Sea basing for this environment without heavy lift support remains untested with smaller platforms like the MH-60S. With the growing asymmetric mine threat and unproven/failed MCM technology for smaller platforms, a heavy-lift replacement for the Helicopter Sea Combat HM squadrons would provide a sound baseline for both MCM and LOG warfighter capability while the MH-60S and Fire Scout augment via a more distributed model.

Conclusion

Now is the time to chart the future of the HSC community. Dogged adherence to the current HSC model may have negative implications for HSC aircrews and will likely result in the same warfighting triviality that has frustrated the community for years. However, if the HSC community is confident enough in its vision to adjust course and take advantage of existing opportunities with a renewed focus on maritime missions and well-planned, achievable warfighting enhancements that strengthen Fleet DL, it can and will be dedicated to safely executing mission sets that warfare commanders demand on a regular basis.

Michael Silver is a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy and an MH-60S pilot with more than 2,600 flight hours. He most recently served as the Operations Officer for Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron Twelve as part of Carrier Air Wing Five, based in Atsugi, Japan.

Jake Moore is a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy and an MH-60S pilot with more than 2,800 flight hours. He most recently served as the Maintenance Officer for Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron Twelve as part of Carrier Air Wing Five, based in Atsugi, Japan.

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

References

1. VADM Thomas Rowden, RADM Peter Gumataotao, and RADM Peter Fanta, U.S. Navy, “Distributed Lethality,” Proceedings Magazine, Jan 2015 Vol. 141/1/1,343, pp. 4

2. “Distributed Lethality,” pp. 1

3. ADM John M. Richardson, U.S. Navy, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority 1.0, 2016

4. FY11-FY16 HSC Community Mishap Data

5. HSC Weapon School SWTIs struggled to maintain a tactical hard deck of 10 flight hours per pilot per month during FY16

6. CNO ADM John M. Richardson, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority 1.0, 2016, pp. 4

7. OPNAV Instruction C3501.384, 17 May 2011

8. “Distributed Lethality,” pp. 1

9. VADM Mike Shoemaker, U.S. Navy, LtGen Jon Davis, U.S. Marine Corps, VADM Paul Grosklags, U.S. Navy, RADM Michael Manazir, U.S. Navy, RADM Nancy Norton, U.S. Navy, Naval Aviation Vision 2016-2025, pp. 44

10. CAPT B. G. Reynolds and CAPT M. S. Leavitt, U.S. Navy, 2016 HSC Strategy, 11 Jul 2016

11. CDR Jeffrey Holzer, U.S. Navy, MH-60S Torpedo Truck Point Paper, 18 Sep 2014

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (April 30, 2013) An MH-60S Sea Hawk helicopter from Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC) 21approaches the flight deck of the amphibious transport dock ship USS New Orleans (LPD 18) during night flight operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Gary Granger Jr./Released