By Scott A. Humr

Technical talent is critical to the Department of the Navy’s bid for technological overmatch in modern warfare. More emphatically, Vice Admiral Loren Selby stated in the Navy’s Naval STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) Strategic Plan, “Strong Naval STEM efforts are critical to America’s future, and are a matter of national security.”1 While technologies are crucial to enabling systems and processes such as Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2), technical talent that informs the development and employment of algorithmic warfare systems is equally important.2

However, the naval services – the Navy and Marine Corps – lack an implementation plan for how they will cultivate STEM talent. To succeed in 21st century naval warfare, the naval services must take a holistic approach to recruiting, education, and retention if they are to effectively compete with today’s advanced threats and the multitude of adversaries. Without clear actions and the right personnel, the naval services’ efforts to improve warfare today will remain, at best, aspirational.

Improving the Foundation

The foundation of a 21st century naval warfare workforce begins with recruiting. Recruiting a technically competent workforce lays the keel of future success. However, the naval services will likely need to improve recruitment of STEM degrees from their largest accession pool for officers such as Navy Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) and other commissioning sources. For instance, the US Navy and the Marine Corps only obtain 19.9 percent and 15.89 of their officer accessions from the Service academies, respectively. Fortunately, all these officers graduate with a Bachelor of Science degree.3 Therefore, with majority of officer accessions deriving from non-military academy sources, the naval services need to do a great deal more for targeting their largest commissioning populations.

The demand for STEM degrees throughout the world is currently outstripping supply. The World Economic Forum reported that there is a global STEM crisis, causing many advanced countries to sound the alarm.4 In the US, a March 2024 brief published by National Science Board reported “We [the United States] are not producing STEM workers in either sufficient numbers or diversity to meet the workforce needs of the 21st century knowledge economy, especially if STEM talent demand grows as projected.”5 Joseph McGettigan, the Director of the United States Naval Academy STEM Center recently stated:

“In 2017 there were 2.4 million positions in the US workforce that went unfilled because there were not enough people with STEM degrees to fill them. It is expected that in 2027 that number will increase by ten percent.”6

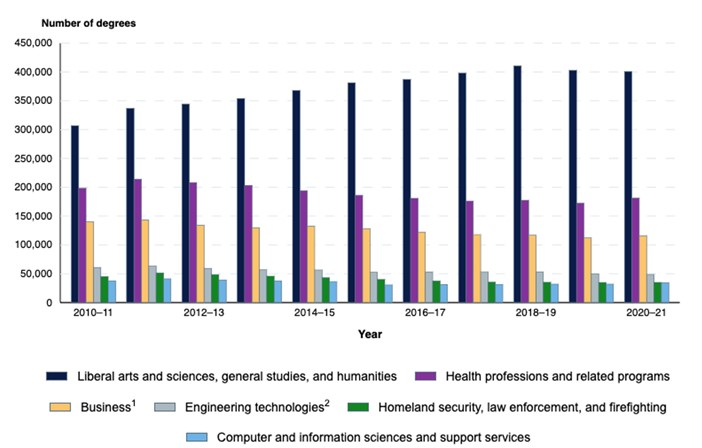

Not surprisingly, the US National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) shows that engineering and related degrees, along with computer and information sciences and support services, only make up a small percentage of all the degrees conferred as shown in Figure 1.7 Hence, these statistics do not bode well for the naval services recruiting and diversity goals for STEM education to support modern warfare. With a growing shortage of STEM talent, the naval services will have to increasingly compete for a smaller portion of this skilled population. Still, the naval services can improve their ability to recruit in a number of different ways.

One way the naval services can improve their recruiting efforts is to influence and increase the pool of eligible candidates sooner. Specifically, the naval services should vector more resources towards their Junior ROTC (JROTC) programs.

Established in 1916, JROTC programs were established to inculcate citizenship and leadership for secondary school students.8 Currently, the JROTC programs are not explicitly designed for military recruitment.9 However in the 2015 Armed Forces Appropriations Bill, Congress voiced its concerns about JROTC’s connections to recruitment by stating:

“The Committee is concerned about the shrinking number of American youth eligible for military service. For nearly 100 years, the Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps [JROTC] has promoted citizenship and community service amongst America’s youth and has been an important means through which youth can learn about military service in the United States. But evidence suggests that some high school JROTC programs face closure due to funding tied to program enrollment levels, adversely impacting certain, particularly rural, populations.”10

While recruitment is not an explicit end-state of JROTC programs, it nonetheless has implications for recruitment.11 For these reasons, the naval services are missing out on an important source of potential recruitment and greater influence over the types of skills needed to support the naval services.

One way the naval services could improve the JROTC program is by making it a more attractive and viable place to grow the next generation of technical leaders. For instance, JROTC programs should place less emphasis on traditional programs of drill and ceremonial activities that the rising generation may consider anachronistic. Rather, JROTC units could structure their programs around more of an Ender’s Game approach:12 creating opportunities such as drone racing leagues, robot building, hackathon coding camps, and E-sports. A more modern conceptualization of JROTC could help shed the stodgy drill and ceremony competitions and create more interest in STEM fields. Such a change would make the military more appealing while also cultivating the skills needed in modern warfare. As a result, the naval services would benefit by increasing the potentially pool for recruitment of this talent.

If the Navy and Marine Corps are to recruit capable citizens to meet the demands of 2030 and beyond, the services need to also address their public-facing social media presence used for their JROTC recruitment. In fact, both Navy and Marine Corps recruitment platforms for their respective JROTC programs require a complete overhaul. The web presence found for these organizations are woefully uninspiring and uninformative. From webpages to social media, the NJROTC and Marine Corps ROTC (MCJROTC) media does not tell a compelling story of service to one’s country or anything remotely intriguing that would drive potential recruits to click, scroll, or swipe deeper into the content. For instance, the Navy’s own NJROTC webpage is a throwback to the way webpages were formatted in the mid-2000s with the content being almost completely text based. Furthermore, NJROTC content on such sites as YouTube is equally uninspiring along with no official Navy presence to speak of on Instagram or TikTok.

If the naval services are going to battle other narratives that compete for attention and tell a compelling story, they must do battle on the same cyber terrain. Warfare knows no bounds and extends to the arena of recruiting the next generation of talent. If the Navy and Marine Corps do not recognize this, then they have already ceded the field of battle to other competing narratives, or worse, the enemy.

Educating for Decision-Making

To compete effectively with modern warfare technologies over the next decade, the naval services must educate and promote continuous learning for better decision-making. Decision-making at the pace of artificial intelligence (AI) is anticipated to be measured in seconds in future war. For instance, the US Army’s Project Convergence which is already testing many AI-enabled applications, advertised they were able to achieve target acquisition to target engagement within 20 seconds.13 Commenting on the challenges Navy destroyer captains face in the Red Sea against Iranian-back Houthis, Admiral Brad Cooper stated they only had nine to 15 seconds to make a decision in an intense environment.14 Therefore, reducing the amount of time to close the kill chains to seconds portends a significant increase in the pace of warfare in the foreseeable future, and by extension, the need for faster human judgments when humans are an integral part of the decision-making process.15 For these reasons, future leaders will not only need to have the best education but will require continuing education to ensure their skills are kept current and relevant to meet such demands.

The naval services must educate to adapt to the changing realities of the Cognitive Age,16 otherwise risk falling behind. However, educating personnel and not placing them in follow-on billets to use their skills and hone their education further through real-world application risks reducing the service’s return on investment in these critical skills. For instance, most US Navy personnel who graduate from the Naval Postgraduate School are not placed in billets that maximizes the use of their degree.17 This is problematic because it demonstrates that the Navy, as publicized in the comprehensive Education for Sea Power (E4S) report, does not have a rigorous selection process for assigning personnel to NPS.

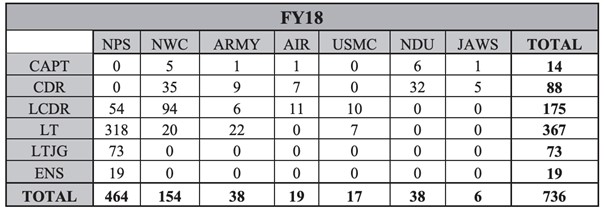

This is clear from the E4S report that the Navy, in particular, is missing the mark on education in at least two ways. First, the E4S showed that the Navy has consistently selected personnel who were either already approved for retirement when entering school or retired from active duty immediately after graduation (p. 331). Figure 2, from the E4S, shows that in FY18 alone the Navy had 736 sailors who fit that description. Second, the E4S stated that, “The variances in training requirements/career progression/sea-shore rotation for each URL (Unrestricted Line) community do not support directly associating a career milestone with graduate education. Communities do not require post-graduation education at the same time within each respective career path” (p. 339). What’s worse is this practice was identified in a 1998 Center for Naval Analysis report, stating that only 37 percent of graduates were sent to utilization tours in relevant coded billets.18 Once again, this demonstrates that the Navy’s system of selection and employment of its most critical asset, its people, falls woefully short and requires an immediate course correction if it is to properly educate and subsequently employ its human talent.

To correct these shortcomings, the Navy should employ a more deliberate board process. For instance, they could adopt a similar approach to the Marine Corps’ graduate education board process.19 Next, both naval services need to identify all billets requiring Master’s-level education that are steppingstones to greater responsibility and promotability. For instance, the Marine Corps should zero-baseline its technical talent in order to realign billets to where they are needed the most.20 Under the Marine Corps’ current policy, units must identify three billets to compensate for a single technically educated service member.21 For this reason, periodically assessing where technical talent needs to reside is crucial for managing this critical talent.

Raising the educational bar and the prestige of such billets will pressurize the system to demand the education and performance necessary to place such billets on par with other career-enhancing positions. This is necessary to ensure only the best and brightest remain in critical leadership roles across all warfare communities.

Retention Requires an Idiosyncratic Approach

It’s no secret that retention is a major concern for the naval services. From the Marine Corps’ efforts to mature the force under Force Design 2030 to the Navy’s own efforts to keep top talent, the naval services will likely continue to struggle given the additional pressures operating under the current recruiting crisis.22 Therefore, all warfare communities should consider several measures that could help with retention. First, all communities should have a clear path to the admiral and general officer levels. For instance, it has been noted that the Navy fills top-level leadership posts in the information warfare communities with unrestricted line officers and not information warfare personnel.23 Such practices not only demonstrate that information warfare leaders may not get to command at the highest levels, but it also demoralizes the community as a whole because it signals technical competence and intimate community understanding are not required to excel.

Second, retention should become more appealing the longer one stays within their community while making meaningful contributions. For instance, bonuses could follow a more tiered system in which the longer one stays, the larger the bonus becomes. This approach can be further incentivized by structuring choices around loss aversion rather than simple lump sum bonuses. This would potentially increase the incentives for receiving a larger bonus the longer one stays.

While there are many additional incentives the services could offer to retain their technical talent, retention still remains idiosyncratic and inducements are not a one-size fits all. Rather, the services need to have the flexibility to provide a range of more bespoke incentives that can be aligned with individual interests. Combinations of geographic preference, additional leave, and bonuses should merit consideration. In short, retention is an important leadership issue that commanders are in a position to positively influence and help shape on a case-by-case basis. Anything short of this will not provide the flexibility needed to help retain the service’s technical talent.

Conclusion

Warfare in the 21st century will demand new approaches for recruiting, education, and retention for the naval services to excel and prevail in battle. As more technologies incorporate AI, autonomy, and even quantum computing, leaders will need to hold the line on sustained investment in technical talent to reap the benefits of both a technologically competent and mature force. Furthermore, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence states that, “the human talent deficit is the government’s most conspicuous AI deficit and the single greatest inhibitor to buying, building, and fielding AI-enabled technologies for national security purposes.”24 Moreover, as the pace of warfare increases, technical talent will have to equally keep apace to ensure the domains they operate in are not ceded to the enemy.

Technically demanding fields require the resources and manpower to have a true force in readiness. Without a clear implementation strategy to address these issues, technical talent will likely exit their service for greener pastures.25 To maintain the United States’ competitive advantage throughout the spectrum of armed conflict, the naval services need to recognize that talent management is a continuous fight and that its people will remain the key driver for winning now and in the future.

Scott Humr, Ph.D. is an active-duty Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Marine Corps with more than 26 years of service. He has worked at every level of the Marine Air-Ground Task Force and has multiple deployments spanning the spectrum of operations. He currently serves as the Deputy for the Intelligent Robotics and Autonomous Systems office under the Capabilities Development Directorate in Quantico, VA.

Endnotes

1. Department of the Navy, Naval STEM Strategic Plan, https://navalstem.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/C31_43-10535-22_Naval-STEM_Strategic-Plan_Final.pdf.

2. Allen, Gregory C. “Six Questions Every DOD AI and Autonomy Program Manager Needs to Be Prepared to Answer.” Washington, DC: 2023. https://www.csis.org/analysis/six-questions-every-dod-ai-and-autonomy-program-manager-needs-be-prepared-answer.

3. “Active Component Enlisted Accessions, Enlisted Force, Officer Accessions, and Officer Corps Tables.” Accessed November 25, 2023. https://prhome.defense.gov/Portals/52/Documents/MRA_Docs/MPP/AP/poprep/2017/Appendix%20B%20-%20(Active%20Component).pdf.

4. Timo Lehne, What can employers do to combat STEM talent shortages?, World Economic Forum, May 21, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/05/what-can-employers-do-to-combat-stem-talent-shortages.

5. National Science Board, Talent is the treasure, March 2024, https://www.nsf.gov/nsb/publications/2024/2024_policy_brief.pdf.

6. Jennifer Bowman, Investing in Future Generations: SSP Receives Hands-On STEM Outreach Training at the US Naval Academy, December 6, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3609182/investing-in-future-generations-ssp-receives-hands-on-stem-outreach-training-at.

7. “Undergraduate Degree Fields.” Accessed November 25, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cta/undergrad-degree-fields.

8. Goldman, Charles A., Jonathan Schweig, Maya Buenaventura, and Cameron Wright, Geographic and Demographic Representativeness of the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1712.html, p.ix.

9. Ibid.

10. US Congress, S. Rept. 113-211 – Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2015, 113th Congress (2013-2014), https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/113th-congress/senate-report/211.

11. Goldman, Charles A., Jonathan Schweig, Maya Buenaventura, and Cameron Wright, Geographic and Demographic Representativeness of the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1712.html, p.x.

12. Bryant, Susan F., and Andrew Harrison. Finding Ender: Exploring the Intersections of Creativity, Innovation, and Talent Management in the US Armed Forces. National Defense University Press, 2019.

13. Freedberg Jr., Sydney J. “Kill Chain In The Sky With Data: Army’s Project Convergence.” Breaking Defense (blog), September 14, 2020. https://breakingdefense.sites.breakingmedia.com/2020/09/kill-chain-in-the-sky-with-data-armys-project-convergence.

14. Norah O’Donnell, Navy counters Houthi Red Sea attacks in its first major battle at sea of the 21st century, June 23, 2024, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/navy-counters-houthi-red-sea-attacks-in-its-first-major-battle-at-sea-of-21st-century-60-minutes-transcript.

15. “Autonomy In Weapon Systems.” https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/dd/issuances/dodd/300009p.pdf.

16. Vice Admiral Ann E. Rondeau, “Technological Leadership: Combining Research and Education for Advantage at Sea,” USNI Proceedings, accessed on March 22, 2021, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/february/technological-leadership-combining-research-and-education.

17. “Education for Sea Power Report.” https://media.defense.gov/2020/May/18/2002302021/-1/-1/1/E4SFINALREPORT.PDF.

18. Gates, William R., Maruyama, Xavier K., Powers, John P., Rosenthal, Richard E., and Cooper, Alfred W. M. “A Bottom-Up Assessment of Navy Flagship Schools: The NFS Faculty Critique of CNA’s Report.” Monterey, 1998. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA358184.pdf#:~:text=there%20is%20a%20low%20utilization%20rate%20(approximately,highest%20per%2Dstudent%20expenditure%20relative%20to%20other%20%22.

19. “Marine Corps Graduate Education Program (MCGEP).” Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201524.1.pdf?ver=2019-06-03-083458-743.

20. Scott Humr and Emily Hastings, Old Wine in New Wine Skins: Marine Corps technical talent requires a new approach, Marine Corps Gazette, June 2024.

21. “Total Force Structure Process.” https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/MCO%205311.1E%20z.pdf.

22. Novelly, Thomas, Beynon, Steve, Lawrence, Drew F., and Toropin, Konstantin.” Big Bonuses, Relaxed Policies, New Slogan: None of It Saved the Military from a Recruiting Crisis in 2023.” Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2023/10/13/big-bonuses-relaxed-policies-new-slogan-none-of-it-saved-military-recruiting-crisis-2023.html.

23. Bray, Bill. “The Navy information warfare communities’ road to serfdom.” Accessed October 23, 2023. https://cimsec.org/navy-information-warfares-road-to-serfdom.

24. “National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence.” Washington, DC, 2021. https://www.nscai.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Full-Report-Digital-1.pdf, p. 3.

25. Nissen, Mark E., Simona L. Tick, and Naval Postgraduate School Monterey United States. “Understanding and retaining talent in the Information Warfare Community.” Technical Report NPS-17-002. Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA (February 2017), 2017. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1060196.pdf.

Featured Image: ATLANTIC OCEAN (Dec. 13, 2021) An unmanned MQ-25 aircraft rests aboard the flight deck aboard the aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Brandon Roberson)

A business can hire-in at every level, shifting employment for new projects and products. The milieu can be fun and exciting! Too bad! The military HR machine is driven by a more concrete, inflexible requirement: to-fill seats of operators and planners necessary to man the defenses. The military cannot hire-in at every level, it needs to develop people from start to finish, designing in flexibility for future changes but without so much as to demotivate personnel floating in endless holding patterns. The needs of the force are precariously balanced with the space to hone the warfighter and the warfighter’s own envisioned personal path. In this naturally messy and un-artful system, retention becomes a critical issue.

A business can hire-in at every level, shifting employment for new projects and products. The milieu can be fun and exciting! Too bad! The military HR machine is driven by a more concrete, inflexible requirement: to-fill seats of operators and planners necessary to man the defenses. The military cannot hire-in at every level, it needs to develop people from start to finish, designing in flexibility for future changes but without so much as to demotivate personnel floating in endless holding patterns. The needs of the force are precariously balanced with the space to hone the warfighter and the warfighter’s own envisioned personal path. In this naturally messy and un-artful system, retention becomes a critical issue. To coincide with this retention push,

To coincide with this retention push,