CIMSEC is committed to keeping our content FREE FOREVER. Please consider donating to our annual campaign now so we can continue to provide free content.

By Dave Andre

“Intelligence means every sort of information about the enemy and his country.” –Clausewitz, On War, 1832

Though it often goes unrecognized, history shows publicly available information (PAI) consistently plays an integral part in the development of the intelligence picture. With the advent of the Information Age, a rapid evolution of technological innovations democratized and decentralized information, creating a digital universe and a surfeit of open source intelligence, or OSINT. In the past decade alone, the world produced more information than it had in the rest of human history. This diffusion of information holds significant promise for the Naval Intelligence community, whose own rich history is replete with examples of OSINT being an integral part of the analytic picture.

From the Age of Sail to the Global War on Terror and beyond, OSINT has proven valuable across the range of maritime operations. Despite this history, Naval Intelligence treats OSINT as an oxymoron, relying on an analytic culture biased against unclassified data. This bias is a mistake. To maintain maritime superiority the Naval Intelligence community needs to orient its collection and analysis toward a truly all-source effort and harness the full potential of OSINT as an intelligence discipline on par with the classified disciplines or it risks ceding the advantage to adversaries and competitors.

OSINT in the Information Age: Problems and Promise

Since the end of the Cold War, the democratization and decentralization of the information landscape resulted in a sharp rise in information quantities, altering the intelligence community. As “publicly available information“ that anyone can lawfully obtain proliferated, the advancements of the Information Age affected OSINT more than any other intelligence discipline. The Internet and cellular technology means individuals enjoy unprecedented access to information, particularly in otherwise underdeveloped regions. Meanwhile, social media makes individuals active participants in the production of information.

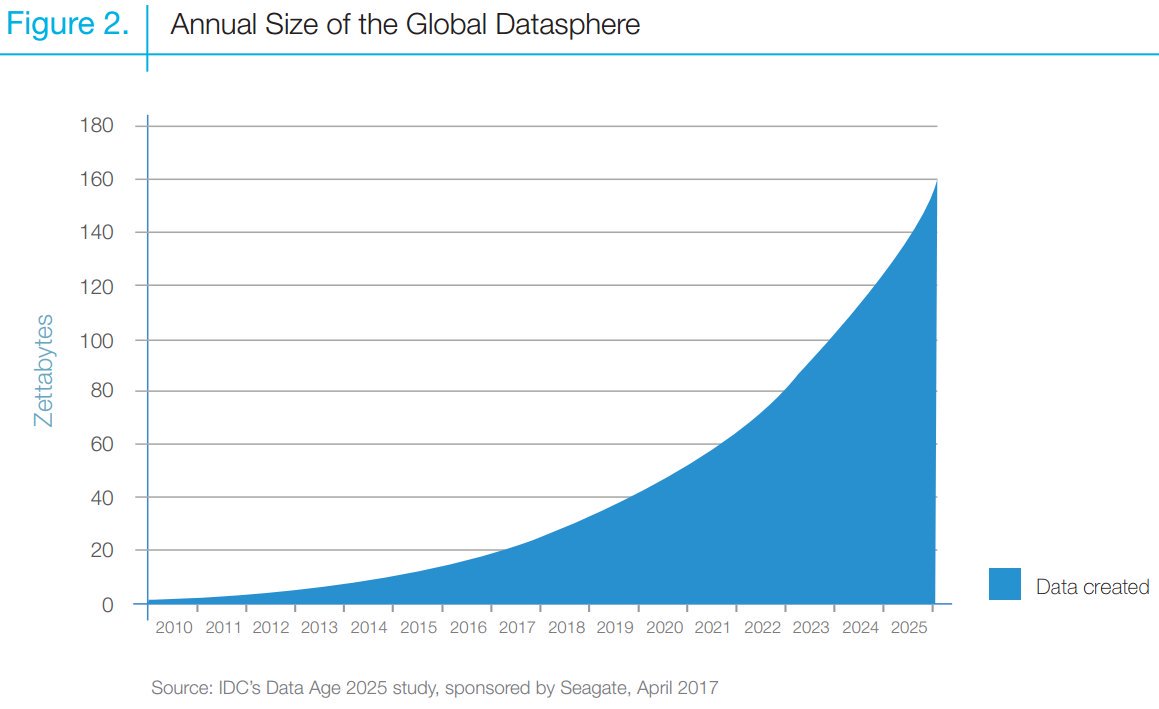

Studies estimate that this digital universe is doubling in size every two years. Globally, an estimated 50 percent of the population has Internet connectivity; 34 percent are active on social media; and there are enough mobile subscriptions that every person on earth could have one. Gone are the halcyon days where OSINT was local papers, television, and radio broadcasts. With each passing year, OSINT expands further past those conventional means and now includes information from the deep web, commercial imagery, technical data, social media, and gray literature with more sources inevitably to follow.

The changes to the information environment affected more than individuals; government agencies and militaries embrace these information platforms, readily divulging information, pictures, budgets, and material status of platforms to the public to champion causes and promote transparency. It is no wonder some experts estimate that 80-90 percent of intelligence originates from OSINT. There is no reason to think these trends will abate soon.

The Naval Intelligence community has been slow to recognize and adapt to these changes in society’s relationship with information. In 1992, speaking at the First International Symposium on Open Source Solutions, Admiral William Studeman discussed the importance of OSINT and the associated challenges that accompanied its acceptance on par with Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), Human Intelligence (HUMINT), and Imagery Intelligence (IMINT). Twenty-five years after Admiral Studeman’s speech, the Naval Intelligence community still treats OSINT at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the established intelligence disciplines, viewing it as unclassified “low-hanging fruit.” This second tier status is shortsighted and history shows it is detrimental to the analytic process.

In a world that moves increasingly faster, OSINT holds a competitive advantage over the traditional intelligence disciplines in terms of speed, quantity, and usability. Sensors, signals, and human sources take time to collect and exploit. In addition, classified means tend to be resource constrained—there simply are not enough assets to cover everything everywhere.

In contrast, PAI, by its very nature, is everywhere and does not require significant resources to exploit. These strengths are why OSINT is “the outer pieces of a jigsaw puzzle” and why it is useful in framing a problem. This framing allows an analyst to focus on effective use of the technical disciplines, thereby acting as a resource multiplier. Acknowledging these factors underscores the important roles that PAI and the resulting OSINT play in the analytic process.

Reliance on the technical disciplines has traditionally come at the detriment of OSINT, but this is unnecessary. Learning how to exploit PAI as an organization necessitates a paradigm shift that begins with training and doctrinal inclusion. This shift needs to occur today. Resource constraints will continue to hamper classified collection methods and as information continues to increase, it will become easier to hide information in plain sight—a real boon for adversaries. The U.S. Navy acknowledged as much in 2013, describing nations that were “simply using the Internet and the commercial global information grid as their own C4ISR system for networking their low-technology military forces.” To buoy this change the Naval Intelligence Community needs to take stock of its history with OSINT.

OSINT Lessons from Naval History: An Important Resource

Naval Intelligence history is replete with successful stories of monitoring, filtering, transcribing, translating, and archiving PAI to produce OSINT. Indeed open source maritime intelligence is as old as the U.S. Navy itself. In Nelson’s ‘old lady’: Merchant news as a source of intelligence, Jane Knight details how, in 1796, intelligence derived through the analysis of a merchant woman’s correspondence with her husband proved useful.1 As the story goes, Frances Caffarena, an Englishwoman married to a Genoese merchant, supplied Admiral Jervis and Lord Nelson’s Mediterranean campaign with a steady stream of information gleaned from open sources. These reports filled a critical gap in intelligence, informing the decision-making of both men as they waged war against Napoleonic France and her allies. This episode marks the beginning chapter of a long history of OSINT supporting and defining the maritime intelligence picture.

Since these early years, OSINT has played a vital role in a wide range of naval operations from Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HA/DR) and Non-Combatant Evacuation Operations (NEOs) to combat on land and sea. During the Second World War, analysts pored over enemy magazines and newspapers and monitored radio broadcasts. These open-source efforts yielded valuable intelligence. One notable example of specific value to Naval Intelligence was the first mention of German submarine tenders through a newspaper article.2

Another integral OSINT lesson from that era was the importance of a distributed network that leverages partner nations’ ability to exploit information with knowledge of local sources and local languages. Such cooperation produced significant results during the Second World War as the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) monitored foreign radio broadcasts across many theaters, sharing the information with the United States. This distributed network is not limited to international partners; it has application across the services as well. One enduring example of an OSINT network is the U.S. Army’s Asian Studies Detachment, which has collected and analyzed PAI on Asian topics since 1947. Developed for U.S. Army tactical units throughout the Pacific, the Asian Studies Detachment has relevance for host of consumers throughout the Pacific region.

Recently, OSINT has been particularly useful in areas—both functional and geographical—that do not typically use classified assets. The 2010 earthquake in Haiti is a good example of how important OSINT can be to U.S. Navy operations. During OPERATION UNIFIED RESPONSE analysts from United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) used social networking sites, blogs, clergy, non-governmental organizations, and the Haitian diaspora to supplement traditional ISR capabilities with firsthand accounts of the situation that focused humanitarian response efforts. This shaped the picture in a way that classified, technical sources could not because of sharing limitations and processing and exploitation timelines.

OSINT’s utility is not limited to non-kinetic operations. The Arab Spring and OPERATION ODYSSEY DAWN exemplify OSINT’s effectiveness in providing intelligence during kinetic operations, especially without “boots on the ground” to provide tactical updates. Throughout ODYSSEY DAWN the Joint Task Force J2 derived valuable intelligence from social media sources such as Facebook and Twitter, with NATO specifically acknowledging that Twitter had become a leading source in developing the intelligence picture and assisted analysts in target development. Additionally, during NEO planning in Libya and Egypt, OSINT was a significant factor in answering intelligence requirements for the 26th MEU embarked on the USS Kearsarge. Meanwhile, OPERATION ATALANTA, the European Union Naval Force’s response to Somali piracy, overcame the dearth of intelligence and the resulting lack of situational awareness by working primarily off PAI; in this case, local newspapers. This proved to be a double-edged sword, as local Somali news sources were heavily biased or censored, oftentimes resulting in “corkscrew journalism” where uncorroborated statements, repeated often enough, turned into truths. These operations illustrate how OSINT may sometimes be the most accurate and timely intelligence available to analysts; and in the case of Somalia, underscore the importance of training and corroboration while using OSINT.

Despite changes over the years, the communal and commercial nature of PAI proves to be its most pertinent contribution to the intelligence picture. OSINT is different from the other intelligence disciplines by virtue of its accessibility. Unlike national sensors, sources, and satellites, a private individual or company usually owns the production method and dissemination of PAI. More often than not, these individuals and companies derive more benefit from making the information available than they do restricting it.

A 2017 Janes IHS article highlighted this relationship, describing how public webcams that overlooked Severomorsk Naval base confirmed the departure of the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov. This episode also highlights the difficulty in determining the veracity of PAI as these webcams were contradicting what news networks were reporting. In a similar manner, Google Earth offers a great example of how PAI can provide valuable OSINT for analysts. A 2013 TIME magazine article covered how Google Earth imagery provided analysts with a wealth of information as they examined China’s construction of its first indigenous aircraft carrier.

Unfortunately, history is also replete with examples of military planners neglecting OSINT to their detriment. In their history on the Battle of Gallipoli, Peter Chasseaud and Peter Doyle detail how a private geological survey omitted from military planning held the key to vital terrain intelligence, which may have mitigated or prevented the ANZAC force’s defeat.3

In one of the most well-known cases of intelligence failure, the aftermath of Pearl Harbor illustrated just how important OSINT could be in the realm of indications and warnings. As the recently established Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) was listening to and translating broadcasts from Japan, they noted increasing hostility towards the United States; the attack on Pearl Harbor commenced before the intelligence could yield value.

The Intelligence Community re-learned the importance of OSINT six decades later as classified data failed to predict, let alone prevent, the Sept. 11th attacks. In the aftermath of the attacks, it became clear there were open source resources that may have offered insight into the attackers plans. A similar assessment was made after the bombing of the USS Cole a year before.4 In each of these examples, the lack of OSINT was just one of many failures, but it is a failure that the Naval Intelligence community perpetuates and one that is relatively easy to fix.

OSINT Tech for the Future Navy

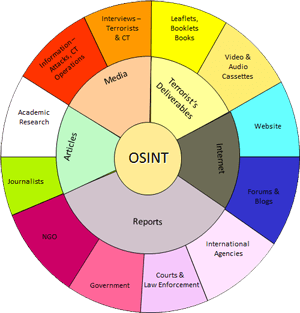

The technological advances of the Information Age are germane to the future of OSINT within the Naval Intelligence enterprise. Across all levels of warfare, PAI represents an opportunity and a challenge to naval intelligence analysts. From the fight against violent extremist organizations (VEOs), which use social media for recruitment and propaganda dissemination, to the understanding of national strategies as world leaders increasingly employ the media to make the case for military operations, OSINT can enable or enfeeble analysis. Irrespective of geography or subject, the Information Age has virtually guaranteed the proliferation of PAI.

Every intelligence discipline has limitations and OSINT’s biggest limitations are the volume and veracity of information. Fortunately, technology continually provides tools to assist in overcoming these obstacles. Some are technical and require training, while others are simple and low-tech, merely requiring familiarization and practice; yet others involve incorporating government technology or commercial subscription services. Regardless of their particular details, these tools are all available to assist the analyst in filtering the overwhelming amount of data available today. These technological advancements also indicate that OSINT is rapidly becoming as technical a discipline as SIGINT or IMINT and Naval Intelligence needs to treat it as such.

There are processes that assist in categorizing useful information versus distracting and irrelevant information and procedures that help determine reliability and credibility. There are increasingly effective ways to use search parameters to cut through the large swaths of information. The Open Source Indicators (OSI) program is one such initiative. A program run by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) under the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), OSI aims at automated and continuous analysis of PAI in an effort to predict societal events.

Additionally, the proliferation of foreign language media will pose a challenge for analysts, though there are promising tools such as the U.S. Army’s Machine Foreign Language Translation Software (MFLTS), which allows analysts to understand foreign language documents and digital media across a variety of platforms. In a similar vein, initiatives like Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA’s) Deep Exploration and Filtering of Text (DEFT) program and Natural Language Processing (NLP) technology aim to help analysts collect, collate, and process information. In addition to these Intelligence Community initiatives, there are commercial programs like Google’s Knowledge Graph that hold promise for intelligence analysts. Using a semantic search, a Knowledge Graph query returns results that determine the intent and context of a searched item, allowing an analyst to avoid the irrelevant responses a traditional keyword search returns and establish relationships between people, places, and events.

Even the socio-technical aspect of social media lends itself to optimization, with Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) now championed, despite privacy concerns, as an emerging intelligence discipline in its own right. Reputable blogs, forums, and chat-rooms – operated by individuals with a strong interest in a subject – act as a form of crowdsourcing where these philes compile large amounts of data for their own interest while simultaneously filling intelligence gaps.

Technically savvy and unencumbered by corporate or government constraints, the individual citizen has proven to be a remarkable source of information for analysts. Whether it is pictures on Instagram of their latest work trip to a naval installation or their Facebook comments about government policies, individuals routinely expose important information to the public. Acknowledging OSINTs role in counterintelligence is at the core of the U.S. Navy’s stringent OPSEC program.

Mainstreaming OSINT Analysis

Whether it is traditional media, social media, or any other element of PAI, the Naval Intelligence community needs to develop the analytic skills to cash-in on this information. Unfortunately, this explosion in information is not without its downside. Concurrent booms of disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda threaten to hamper the analysis of PAI just as social media has become a tool for disseminating fake news. Much as these information distractions present a challenge, they also underscore the importance of all-source analysis. The OSINT landscape has changed dramatically since the days of the Cold War. Despite these changes, the core challenge of open source analysis remains the same — parsing the salient from the trivial — and that takes skill.

It is not enough to recognize the utility of OSINT; the Naval Intelligence community must train, equip, and organize around the process of collecting and analyzing PAI. It is time to adhere to the guidance put forth since the 1992 Intelligence Reorganization Act, which acknowledged the importance of “providing timely, objective intelligence, free of bias, based upon all sources available to the U.S. Intelligence Community, public and non-public.” More explicitly, in 1996, the Aspin-Brown Commission concluded, “a greater effort also should be made to harness the vast universe of information now available from open sources.”Again, in 2004, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act (IRTPA) emphasized the need for the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) to “ensure that the IC [Intelligence Community] makes efficient and effective use of PAI and analysis.” Despite these repeated issuances and a long history that demonstrates the importance of OSINT, the Naval Intelligence community continues to pay scant attention to OSINT relative to other intelligence disciplines.

Currently, the Naval Intelligence community has no formal training pipeline to develop open source analysts, no formal guidance on collection methods or best practices, and it receives little direction from Navy doctrine. As such, OSINT within Naval Intelligence resides (unreliably and disparately) at the grassroots level, where intrepid intelligence professionals and the occasional Mobile Training Team (MTT) delve into the realm of open source.

This approach is akin to a person who knows just enough information to be dangerous. PAI is going to continue to increase in scope and value, but also difficulty, which is precisely why the Naval Intelligence community needs to develop a formal training pipeline so they can begin addressing the problem from the bottom-up. In the meantime, the Navy can leverage open-source training that exists within the larger Intelligence Community or employ private organizations like Jane’s IHS that offer OSINT training on effective collection methods, monitoring social media, conducting safe and optimized searches, and conducting analysis of PAI. Such training will allow analysts to exploit the full potential of OSINT and move past mere regurgitation of previously reported information.

The lack of a formal training pipeline is not the only limitation that undermines the realization of OSINT’s role in the Naval Intelligence community. OSINT is barely mentioned in Naval doctrine, all but ensuring that the training and cultural issues will remain. Moreover, the absence of OSINT in doctrine provokes discord amongst intelligence professionals and creates an environment where commanders default toward a pre-conceived emphasis to classified sources.

This is where the Navy can learn a lesson from the other services and the larger intelligence community, which have all made significant steps towards including OSINT in their doctrine. These lessons, borne of years of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, lend themselves to adaption by the Navy. For example, both the Marine Corps and Army detail the collection and production of OSINT, considerations to judge reliability and credibility, and reporting and dissemination procedures. Similarly, both DIA and NGA recognize the importance of OSINT and the emerging technologies that support its exploitation.

Adding OSINT to doctrine will work in tandem with a formal training pipeline and change the culture from top-down. Together these changes can overcome what is perhaps the greatest barrier that OSINT faces: an analytic cultural that does not afford OSINT the same respect as other disciplines. A 2005 report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) summed up this sentiment, stating “analysts tend to give more weight to a folder stamped ‘SECRET’ than to the latest public broadcast of an Al Qaeda message on Al Jazeera Satellite television network.” Changing the culture will take time and money, but not changing the culture will certainly be more costly. The time is perfect, the officers and sailors joining today are accustomed to social media and the Internet, as are our adversaries.

Conclusion

The referenced instances of OSINT’s successes and failures are not exhaustive, but serve as examples of the breadth and depth of OSINT support to the intelligence picture. History shows that OSINT has always been important, but the future indicates that OSINT will play an increasingly critical role in the intelligence picture. The Information Age profoundly altered the way PAI is produced, collected, analyzed, and disseminated, which has led to changes in the quality and quantity of that information.

Fortunately, the Information Age has also brought with it a host of tools to address these changes in the information landscape. It is time the Naval Intelligence Community transforms its approach and attitude to OSINT. Disregarding these changes risks a painful reiteration of past lessons where intelligence failures were the result of poor policy, not analysis.

LT David M. Andre is a prior enlisted Intelligence Specialist, and has served as an Intelligence Officer onboard the USS ENTERPRISE (CVN 65), an Intelligence and Liaison Officer assigned to AFRICOM, and as N2 for COMDESRON SEVEN in Singapore. He is currently serving as an analyst at STRATCOM’s JFCC-IMD. He can be reached at dma.usn@gmail.com.

References

1. Jane Knight, “Nelson’s ‘old lady’: Merchant news as a source of intelligence: June to October 1796,” Journal for Maritime Research, Vol. 7, Issue 1, (2005): 88-109, DOI: 10.1080/21533369.2005.9668346.

2. William J. Donovan, “Intelligence: key to Defense” LIFE, 30 Sep 1946. Vol. 21, No. 14; 108-122.

3. Peter Chasseaud and Peter Doyle Grasping, Gallipoli: Terrain, Maps and Failure at the Dardanelles, 1915. (London: Spellmount, 2005): 173-174.

4. Arnaud De Borchgrave, Thomas M. Sanderson, John MacGaffin, Open Source Information: The Missing Dimension of Intelligence: A Report of the CSIS Transnational Threats Project, CSIS Report (2006):3.

Featured Image: Information Systems Technician 2nd Class Michael Tolbert, left, and Information Systems Technician 2nd Class An-Marie Ledesma upload geographical data onto tactical Apple iPads for combat operations in the Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 17 operations room aboard the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70). Carl Vinson and Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 17 are conducting maritime security operations and close-air support missions in the U.S. 5th Fleet area of responsibility. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Christopher K. Hwang/Released)