Read Part 1 on Combat Training. Part 2 on Firepower. Part 3 on Tactics and Doctrine. Read Part 4 on Technical Standards.

By Dmitry Filipoff

Material Condition and Availability

“The very gallantry and determination of our young commanding officers need to be taken into account here as a danger factor, since their urge to keep on, to keep up, to keep station, and to carry out their mission in the face of any difficulty, may deter them from doing what is actually wisest and most profitable in the long run…” –Admiral Chester Nimitz

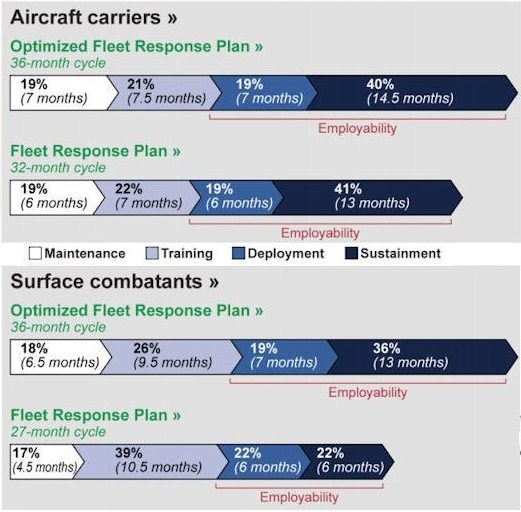

The post-Cold War Navy made major reforms to a fundamental operating construct of the fleet, its readiness cycle. The readiness cycle of the Navy is a standardized period of maintenance, training, deployment, and sustainment phases that produce ready naval power within a specified timeframe. The deployment schedule the Navy operates on is tied to how its forces are moving along at various phases in the cycle and when they become available for use after having met their needs.

A readiness cycle should be predictable in that it regularly produces naval power of consistent quality in the absence of major contingencies. From the perspective of a competitor it should be unpredictable in that it has enough margin where it can effectively surge and sustain a large number of forces on short notice to surprise and overwhelm foes if need be. It should then be able to recover from a surge in a reasonable timeframe and reset itself in stride. It should also maintain some consistency while allowing ships to undergo extensive maintenance and upgrade periods as needed.1

A readiness cycle’s viability is based on the deployment rate it serves, where a higher rate of deployment can come at the cost of more unmet needs. A cycle cannot resemble a taut rope, but rather one that keeps enough slack to maintain the necessary resilience and flexibility. These qualities are predicated on respecting the material limits of naval power. National security strategy is bounded by these limits.

During the power projection era the Navy’s readiness cycle lost its discipline. In less than 20 years the Navy has deployed under four separate cycles, and where the two most recent constructs are attempting to restore order and arrest systemic shocks that spiraled out of control. These shocks unbalanced the Navy, sapped its ability to surge the fleet, and incurred significant strategic risk with respect to great power war.

The Power Projection Era and Readiness Cycle Reform

“We kind of lost our way a few years back when we were all doing everything we could to get airplanes and ships forward into the fight…it went on and on and on, and I think that’s where the stress of not only the people and the equipment but also the processes started to break down.” –Vice Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Bill Moran

In the new national security environment of the power projection era the Navy felt it needed to increase its ability to surge the fleet on short notice as well as increase its continuous presence in forward areas. The Navy sought to accomplish this in part by making major changes to its readiness cycle through a major reform known as the Fleet Response Plan. The Navy was especially focused on increasing surge capacity, where according to the Naval Transformation Roadmap (2003):

“The recently created Fleet Response Plan (FRP) will significantly increase the rate at which we can augment deployed forces as contingencies require. Under the regular rotation approach…the majority of ships and associated units were not deployed and thus at a point in their Inter-Deployment Readiness Cycle (IDRC) that made it difficult and expensive to swiftly ‘surge’ to a crisis, conflict or for Homeland Defense. The FRP features a change in readiness posture that institutionalizes an enhanced surge capability for the Navy…a revised IDRC is being developed that meets the demand for a more responsive force. With refined maintenance, modernization, manning and training processes, as well as fully-funded readiness accounts, the Fleet can consistently sustain a level of at least 6 surge-capable carrier strike groups, with two additional strike groups able to deploy within approximately 90 days of an emergency order.”2

This surge policy was implemented and approved of just after the Iraq War began. Seven carrier battle groups conducted forward operations in support of the invasion of Iraq, with an eighth deployed in the Pacific. Five of those eight battle groups and air wings had already participated in Operation Enduring Freedom just a year before. A year later seven carrier groups simultaneously deployed in 2004 for the Summer Pulse exercise that intended to demonstrate the FRP’s surge capability.3 In relatively quick succession the Navy surged the fleet multiple times at levels not seen since the Vietnam War.4

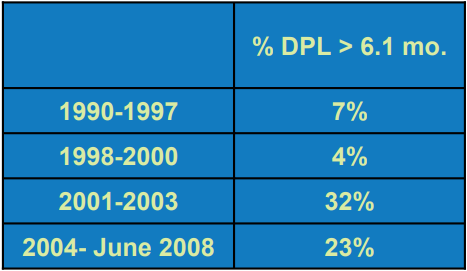

One of the most far-reaching changes of habit was an increasing willingness to extend deployment lengths beyond what was previously the norm. Since 1986 the Navy had rigorously adhered to a maximum deployment length of six months, a policy the Global Navy Presence policy described as “inviolate.”5

New strategies concerned with adding forward presence and surge capability often encouraged the Navy to lengthen deployments. From Operation Desert Storm to 9/11 the Navy only granted a few dozen exceptions to the six-month deployment policy. It then granted almost 40 exceptions for Operation Enduring Freedom in 2002, and a year later it granted almost 150 more in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.6 What was once the exception became the norm as ships continued to deploy in excess of six months many years after the large surges that accompanied the starts of those campaigns. From 2008-2011, carrier strike group deployments averaged 6.4 months, which then climbed to 8.2 months in the next three years.7

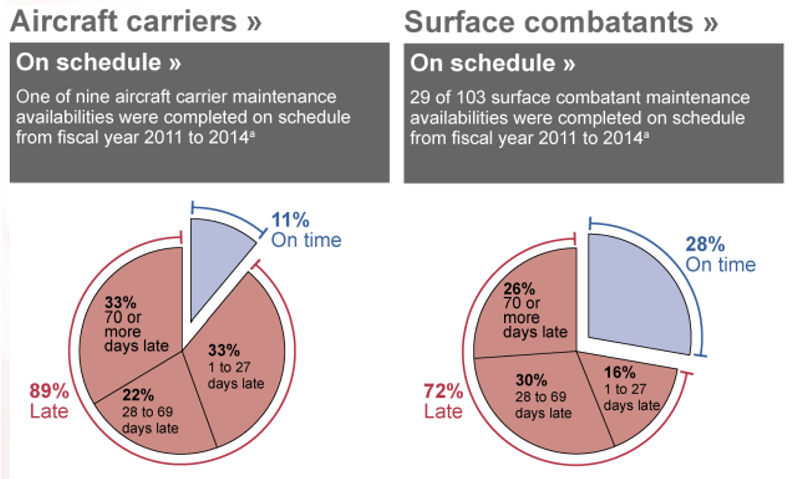

This operating tempo and the Fleet Response Plan proved to be fundamentally unstable and unsustainable. The effects forced the Navy to repeatedly compromise and improvise its schedules to make ends meet and maintain its deployment rate.

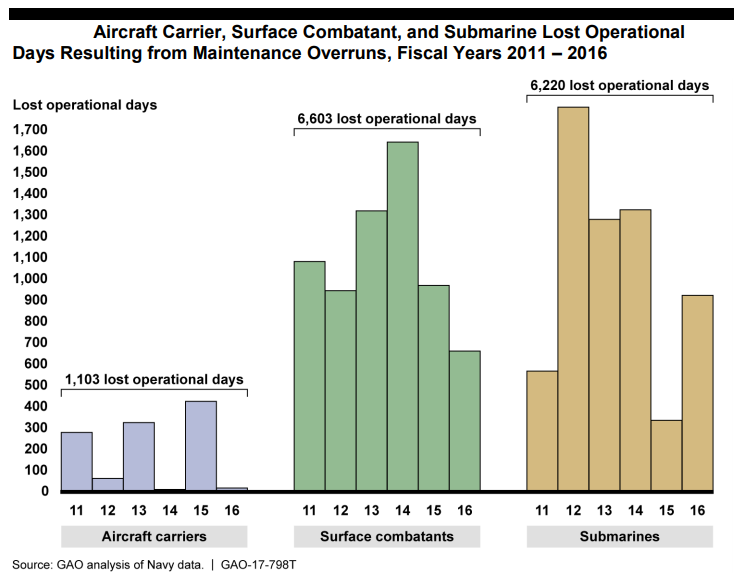

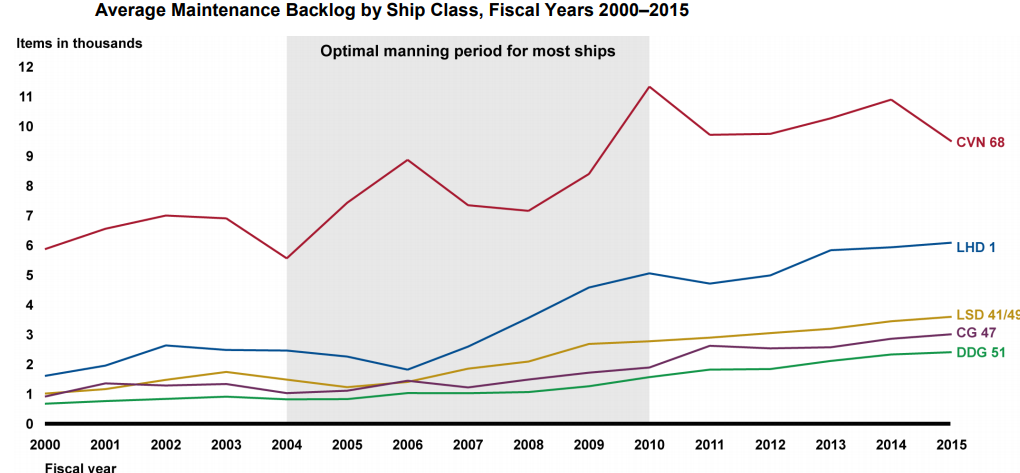

Some ships already on deployment had their tours extended on short notice. Longer deployments then created greater maintenance demands, where ships often saw their expected maintenance phase grow by many months. Some even tripled in length.8 Maintenance overruns started happening more often than not, forcing other ships to deploy sooner to cover the planned operations of ships that found themselves stuck in prolonged maintenance. Meanwhile backlogs and equipment casualty reports were mounting as the fleet was pushed harder and harder and maintenance troubles grew more severe. In spite of all of this the demand for naval power only kept growing.9

Navy leadership eventually admitted the system was falling apart:

“Unfortunately, the Navy was rarely able to execute the FRP as designed…schedules were adjusted to meet changing combatant-commander demands, maintenance delays, and crisis response. This has caused significant unpredictability for our sailors and maintenance teams, while revealing a host of inefficiencies…Inefficient readiness production and unpredictable schedules are never good, but they have become unsustainable.”10

As negative effects spiraled out of control and cascaded across the Navy’s timetables it had little choice but to take corrective action. A new readiness cycle known as the Optimized Fleet Response Plan (OFRP) was implemented in 2014 in an attempt to bring “predictability” to the cycle.

Among many changes OFRP slightly reduced the amount of time ships would be deployed from 25 percent to 22 percent of the cycle, slowing material degradation and allowing more time for maintenance. A significant amount of time was added to the sustainment phase that follows deployments and comes before the maintenance phase. The surface fleet in particular benefited from a significant extension of the sustainment phase. Warships in this phase are supposed to be surge capable and available for hard training. However, the ships and crews are usually quite spent after six to eight months of forward operations, and more importantly the Navy has typically allocated little funding for significant amounts of training or operating in the sustainment phase.11 Perhaps the most value that comes from the sustainment phase is that ships can use it to get caught up on what maintenance they can.12

Navy leadership described a key reform that OFRP attempted, in that it “transitions fleet production of operational availability from a demand based to a supply based model.”13 This new model will hopefully be “disciplined” and “predictable” in nature.14 However, a supply-based model is the only sort of readiness scheme a Navy can realistically run on.

No fleet that wishes to maintain its consistency can operate under a demand-based model for long because it will eventually spend itself. Naval power is extremely flexible and mobile, where ships can independently conduct many sorts of missions and travel hundreds of miles a day. Operating remotely in international waters can temper foreign political sensitivities such as those that are often associated with hosting foreign troops on land. Naval power can often streamline operations by not having to rely as much on the bureaucracies of foreign countries. All of these qualities can make naval power very attractive to theater commanders and the interagency.

However, a Navy must guard its long-term condition by successfully saying no to excessive demand signals more often than not, which is how a supply-based model is preserved over time. To subscribe to a demand-based model is to put the fleet’s material condition in the hands of combatant commanders whose official responsibilities are to use forces for near-term operations, not maintain them for long-term well-being.

Even if it operates under something more sustainable the consequences of recent deployment rates can come back to haunt the Navy and force it to pay another price later.

Hard deployment rates accelerate material degradation and can shorten the service lives of ships.15 This creates long-term risk because shortened service life can prompt early retirements. Concerns about gaps in presence and fleet numbers can be exacerbated in the future by ships being forced into early retirement as they become increasingly expensive and time-consuming maintenance burdens.

Now in order to grow and preserve fleet size the Navy is heavily counting on its ability to modify and extend the lives of many ships past the original estimates.16 But the significant maintenance debts incurred under recent deployment rates will no doubt complicate this endeavor, and add to the Navy’s fears of seeing the fleet shrink even further.

Fleet Availability and National Security Strategy

“I didn’t have a full appreciation for the size of the readiness hole, how deep it was, and how wide it was. It’s pretty amazing…You have a thoroughbred horse in the stable that you’re running in a race every single day. You cannot do that. Something’s going to happen eventually.” –Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer

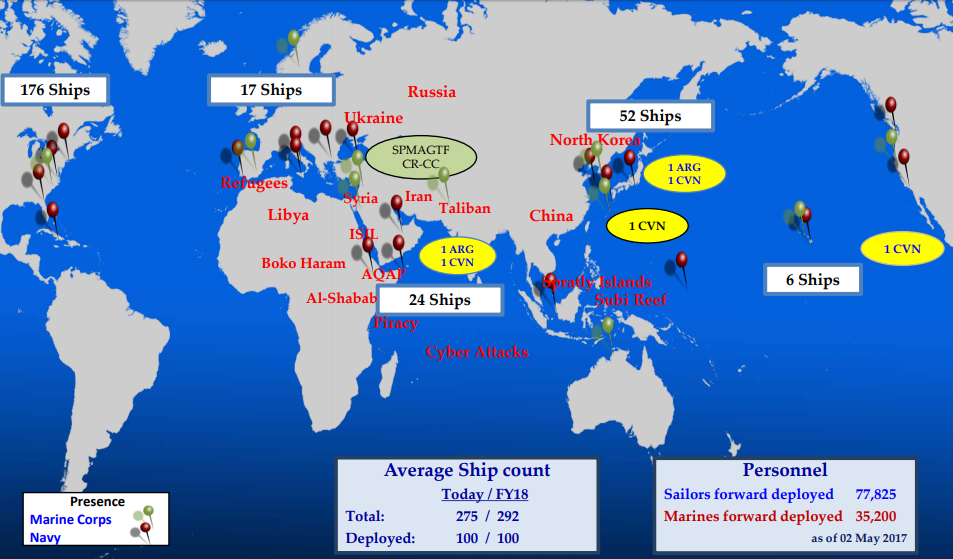

Gaps in forward naval presence could become the new normal and not just as a result of lacking readiness discipline. Rather, it may be the product of the Navy and the Department of Defense finally coming to terms with the limits of what can be done with a much smaller fleet. Reconciling with this truth could mark a major strategic shift in how the U.S. envisions using its Navy for war and deterrence.

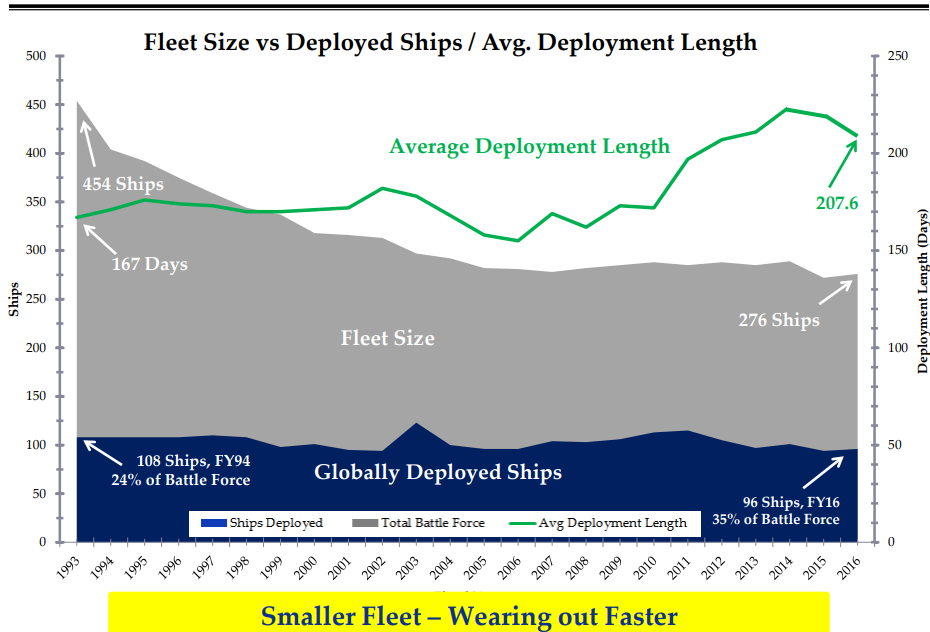

In spite of increasing demand signals and widespread fluctuations across the Navy’s workup cycles one key thing remained consistent. For at least the past 25 years the Navy steadily deployed around 100 ships per year for about six months at a time. The Navy tried to maintain this deployment rate despite the fact the fleet shrunk by over 40 percent in the same timeframe.

Fleet size helps dictate what deployment levels can be sustained. In order to maintain round-the-clock presence in a distant part of the world around four ships are needed for every one kept forward.17 This comes from how the deployment phase is about a quarter of the time within the workup cycle under the FRP or the OFRP. Forward-deployed naval forces such as those homeported in Japan are far more efficient by being based in theater, but forward-based units are a small minority of the force. Rotational crewing can also increase availability, but this also applies to a minority of the force and no large surface combatants or flattop capital ships operate under this scheme. Four ships for every one forward translates into something quite larger than the 280-ship fleet that exists today if the Navy wishes to keep deploying 100 ships per year for six months at a time.

The Navy was able to maintain constant presence in certain parts of the world through this deployment rate. The strategic argument for presence had long been a driving force behind the power projection focus, and where it was widely reported in 2015 that a carrier presence gap emerged in the Middle East for the first time in eight years.18 Guaranteeing constant presence was used to justify crushing deployment rates for years. Perhaps this is why it was so difficult to break away from deploying 100 ships per year on six-month deployments. Dropping below this rate could normalize presence gaps in certain areas, thereby triggering a major strategic revision of how the fleet could be used in key parts of the world.

Gaps in presence are poised to become more frequent in any case. It is not that the Fleet Response Plan itself was a failure, but that the strategy it tried to serve became highly unrealistic for a shrinking Navy. Recent experience proves the Navy will wreck itself if it tries to continue deploying around 100 ships per year for over six months at a time. Therefore this deployment rate may actually represent a supply-based ceiling that was set many years ago by a much larger fleet, instead of a true demand-based model. Despite the fact that demand for naval power substantially increased throughout the power projection era the number of ships being deployed held steady.

However, what was once a supply-based limit may have morphed into demand-based pressure as the shrinking fleet became more stretched and strained. Maintenance troubles became severe enough to induce presence gaps in this deployment rate despite the Navy’s vigorous efforts to improvise timelines to prevent those gaps from happening. Somewhere along the way the fleet shrunk so much that eventually predictable presence could not come without predictable maintenance, putting the Navy at a tipping point.

The Navy’s latest deploying construct, known as Dynamic Force Employment, was implemented this year. One of its main features appears to include regular three-month deployments, which are half as short as the deployments of the past 30 years. By bringing units home much earlier the Navy won’t spend most of a ship’s readiness in a single stretch and in a forward area. This will conserve enough readiness to allow ships to more confidently deploy again if need be instead of possibly reusing tired ships and crews coming off long deployments. This will then create greater overlap in the employability of the Navy’s ships, allowing the fleet to better surge in larger formations. Ships can also use that extra time to get caught up on maintenance, conduct force development operations near home, or be better primed to surge. Perhaps Dynamic Force Employment is the break the Navy finally needed.

This operating concept could also represent a major shift in how the nation envisions using the Navy for winning and preventing wars. A major strategic justification for emphasizing continuous forward presence was the concept of deterrence by denial. By steadily maintaining naval forces in forward areas the Navy would shut down threatening ambitions by ruling out an adversary’s options for sudden strikes and quick, fait accompli victories. Forward presence also allows ships to frequently engage in foreign partnership operations and security cooperation. These operations can build constructive relationships, enhance partners’ skills in providing for their own security, and shape regions toward a more positive outlook of the U.S.19

Gaps in presence can change the strategic calculus of military options and deterrence. With gaps the Navy would not be as able to prevent sudden hostile actions or victories, but instead it could be reactively deployed to punish adversaries, roll back their gains, and prevent consolidation. This concept is strongly reinforced by shifting to an operating posture that emphasizes surging forces from home instead of continuously maintaining them abroad for presence. Defense Secretary James Mattis suggested this significant shift behind Dynamic Force Employment:

“They’ll be home at the end of a 90-day deployment. They will not have spent eight months at sea, and we are going to have a force more ready to surge and deal with the high-end warfare as a result…You can bank readiness by decreasing forward presence – that is, if you have fewer forces forward deployed…you have more to push forward when you want them. In other words, it’s punishment rather than deterrence — you surge after the enemy has made its move.”20

This suggests deterrence by denial through steady presence has been deemphasized in favor of responding to hostile action through reactively surged force.

Deploying ships for only three months at a time under this latest construct will dramatically lower presence even further. Dynamic Force Employment may therefore signal the removal of forward naval presence from an overriding position in national security strategy. This year the Navy has gone about six months without operating a carrier group deep in Middle Eastern waters, and with little fanfare compared to the previously mentioned two-month presence gap in 2015.21 Under this new construct presence gaps could have been made much more acceptable, and especially for the sake of improving surge capacity.

https://gfycat.com/gifs/detail/FixedDentalHarpseal

A tracker displaying Navy deployments over a six-month period. Note the absence of a carrier strike group operating deep in Middle Eastern waters for almost all of the time period. (Types of major ship formations: ARG = Amphibious Ready Group, ESG = Expeditionary Strike Group, CSG= Carrier Strike Group. ARGs and ESGs are centered on an amphibious assault ship as the primary capital ship of the formation. Formations here are named after their main capital ship. Tracker source: U.S. Naval Institute News Fleet Tracker, sponsored by the Center for Naval Analyses)

This could be a major pivot in the Navy’s posture toward great power competition and away from power projection. It could also be the long overdue acceptance of the strategic downgrade in presence that occurs when the Navy of a geographically isolated superpower shrinks to half its size in a span of 15 years.22 For American naval supremacy it could mark the end of an era, or a new beginning.

Surge Capacity and Strategic Credibility

“I had always supposed that the subdivision in time of peace of a nation’s fighting units into numerous independent squadrons was due more to personal reasons than to a consideration of the principles of naval training and strategy—which latter seems to be more correctly illustrated by the rapid concentration that takes place when war is imminent…where the command of the sea is involved, a nation is not deterred from going to war by the state of dispersion of a rival nation’s battleships, but by the knowledge that he has a certain number…and that they have been continuously trained to a high degree of individual and fleet efficiency by concentration in one or more large fleets.” – Lieutenant Commander William Sims, 1906.

The damage done by years of excessive deployment rates has already degraded the Navy’s credibility. Regardless of any demand for presence maintaining latent surge capacity has always been one of the most vital national security requirements for a superpower. It gives the nation the flexibility it needs to effectively respond to major contingencies. War plans must be underpinned by realistic understandings of surge capacity to know how much force can be brought to bear in those crucial first weeks and months of a major war.

Significant declines in surge capacity can force revisions to war plans, and where a diminished ability to surge the fleet can increase strategic risk if the Navy cannot respond as well to major events. This makes the state of the fleet’s maintenance and material condition a major limiting factor of strategic consequence because these variables largely determine the Navy’s ability to surge its forces on short notice.

If the Navy has to suddenly surge in large numbers it will have to make difficult decisions on which ships it will bring forward and which ships it will leave behind. Major contingencies could easily force the Navy to pull forces from beyond those that are in the “employable” windows of the workup cycle. At any given moment many ships are undergoing deep maintenance and complex upgrades which makes it more difficult to deploy them on short notice. The deeper and more troubled the maintenance work of a ship the harder it will be to surge it with confidence. In the aftermath of last year’s fatal collisions the Navy’s “can-do” culture was cited as a major factor in normalizing excessive risk by deploying ships in worsening condition for years. But how “can-do” will the Navy be when it really has to surge for a major crisis?23

The viability of a readiness cycle can be measured by its ability to preserve a given amount of surge capacity against the wear-and-tear of regular operations. This is how a supply-based model can drive its discipline. Maintaining ships and aircraft in a good state and knowing how to firmly control their maintenance needs is central toward preserving surge capacity and understanding material limits. But a demand-based model and its inherently unstable nature will eat away at that supply and make maintenance less predictable. Navy leadership testified before Congress on the nature of the demand-based model and the mounting strategic liabilities it was incurring:

“…we continue to consume our contingency surge capacity for routine operations. It will be more challenging to meet Defense Strategic Guidance objectives of the future. Ultimately, this is a ‘pay me now or pay me later’ discussion.”24

Exactly how much surge capacity has the Navy sacrificed? Navy leaders testified that a major goal of OFRP was to “restore” the Navy to a three-carrier level of surge capacity.25 This is half the six-plus-two construct that was the goal of the Fleet Response Plan, suggesting a staggering loss of over half the Navy’s surge capacity within about ten years. But perhaps the Navy just overestimated itself. When the GAO suggested in 1993 that a 12-carrier force could surge seven battle groups within 30 days the Navy wrote the idea off as an “overly optimistic picture of carrier battle group surge capability.”26 Yet the goal of the Fleet Response Plan was not much different.

The U.S. is heavily disadvantaged by geography when it comes to military responses in that it must cross large oceans to surge to the front. Great power competitors such as Russia and China can easily enjoy steep advantages in time, space, and numbers because major contingencies are more likely to break out in their front yard. By operating so much closer to home great power competitors will have a vastly superior ability to surge at the start of sudden war. By comparison the U.S. will have relatively few forward forces, will have to surge across great distances, and may have to heavily rely on regional allies where many are easily overmatched by Russia or China. The deterrent value of forward forces and certain allies could make them more of a tripwire instead of a roadblock.

Surging is vital to winning the high-end fight because of its especially intense character. War at sea in particular has always been fairly deterministic when it comes to firepower overmatch because of the concentrated nature of naval capability. This trend is greatly magnified in the missile age where now only one hit can easily be enough to put a ship out of action, meaning a very small advantage in firepower can quickly snowball into decisive effects. This is especially true when modern war at sea can consist of forces unleashing dozens if not hundreds of missiles at one another’s ships within minutes. High-end naval combat could easily witness extreme amounts of rapid overkill if warship defenses fail to keep up even slightly. As Wayne Hughes the renowned thinker on naval tactics describes it, “It is demonstrable both by history and theory that not only has a small net advantage in force…often been decisive in naval battles, but the slightly inferior force tends to lose with very little to show…when committed in battle, the heart of a fleet can be cut out in an afternoon.”27

A fleet that is even slightly outgunned can easily lose. This makes the ability to powerfully surge foundational to success. By swallowing surge capacity to feed forward presence the Navy’s ability to win great power war has been degraded in a most critical way. A Navy that is serious about its credibility for the high-end fight will vigorously defend its material readiness for the sake of surge capacity.

Instead, the power projection Navy compromised its discipline. It lowered key readiness standards, set extreme surge requirements, and made lengthy deployments that were once considered rare the new normal.28 Pursuing more presence in forward areas and having more surge capacity from home are two opposite ambitions for orienting readiness. The Navy tried to do both, and with a shrinking fleet.

The Navy is now less sure of its own limits after having long exceeded them. If a pressing contingency breaks out tomorrow could the Navy effectively surge and then quickly rebound? Could the Navy surge enough ships to arrest a short sharp war by China, such as in a Taiwan scenario? After pushing too hard for too long the U.S. Navy finds itself tired, unbalanced, and less sure if it has either the forward presence or the surge capacity to stop great power war in its tracks.

Part 6 will focus on Strategy and Operations.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

References

1. Megan Eckstein, “U.S. Fleet Forces: New Deployment Plan Designed to Create Sustainable Naval Force,” U.S. Naval Institute News, January 20, 2016. https://news.usni.org/2016/01/19/u-s-fleet-forces-new-deployment-plan-designed-to-create-sustainable-naval-force

Excerpt: “We’re trying to get four things out of OFRP: we’ve got to have a schedule that’s capable of rotating the force, meaning sending it on deployment; surging that force in case we have to go to war; maintain and modernize that force so that we can get it to the end of its service life; and then if you had to go to war or if you had some other catastrophe, be able to reset the whole thing in stride, which the previous iteration didn’t have that capability…”

2. Naval Transformation Roadmap 2003, Assured Access & Power Projection From the Sea… http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/navy/naval_trans_roadmap2003.pdf

3. For scale of recent surge deployments see:

Roland J. Yardley et. al, “Impacts of the Fleet

Response Plan on Surface Combatant Maintenance,” RAND, 2006. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2006/RAND_TR358.pdf

Excerpt: “Operation Iraqi Freedom featured the largest naval deployment in recent history, with more than 70 percent of U.S. surface ships and 50 percent of U.S. submarines underway, including seven CSGs, three amphibious readiness groups, two amphibious task forces, and more than 77,000 sailors participating…”

Benjamin S. Lambeth, “American Carrier Air Power at the Dawn of a

New Century,” RAND, 2005. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2005/RAND_MG404.pdf

Excerpt:

“As the Iraqi Freedom air war neared, the Navy had eight carrier battle groups and air wings deployed worldwide, including USS Carl Vinson and her embarked CVW-9 in the Western Pacific covering North Korea and China during the final countdown. Five of those eight battle groups and air wings had participated in Operation Enduring Freedom just a year before. With five carrier battle groups on station and committed to the impending war, a sixth en route to CENTCOM’s AOR as a timely replacement for one of those five, a seventh also forward deployed and holding in ready reserve, and yet an eighth carrier at sea and ready to go, 80 percent of the Navy’s carrier-based striking power was poised and available for immediate tasking. During the cold war years, having eight out of 12 carriers and ten air wings deployed at sea and combat-ready at the same time would have been all but out of the question.”

For Summer Pulse see:

“Summer Pulse 2004,” All Hands Magazine, September 2004. https://www.navy.mil/ah_online/archpdf/ah200409.pdf

Caveat offered by GAO: “Summer Pulse 2004 was not a realistic test because all participating units had several months’ warning of the event. As a result, five carriers were already scheduled to be at sea and only two had to surge. Because six ships are expected to be ready to deploy with as little as 30 days’ notice under the plan and two additional carriers within 90 days, a more realistic test of the Fleet Response Plan would include no-notice or short-notice exercises.”

4. General Accounting Office, “Cost-Effectiveness of Conventionally and Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carriers,” August 1998. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GAOREPORTS-NSIAD-98-1/pdf/GAOREPORTS-NSIAD-98-1.pdf

5. Heidi L.W. Golding, Henry S. Griffis, “How Has PERSTEMPO’s Effect on Reenlistments Changed Since the 1986 Navy Policy?” Center for Naval Analyses, July 2004. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1014531.pdf

For “inviolate” reference: Raymond F. Keledei, “Naval Forward Presence,” Naval War College student thesis, October 23, 2006. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a463587.pdf

6. Raymond F. Keledei, “Naval Forward Presence,” Naval War College student thesis, October 23, 2006. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a463587.pdf

7. Admiral Bill Gortney and Admiral Harry Harris, USN, “Applied Readiness,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, October 2014. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-10/applied-readiness

8. Megan Eckstein, “USS Dwight D. Eisenhower Repair Period Triples in Legnth; Carrier Will be in Yard Until 2019,” U.S. Naval Institute News, September 24, 2018. https://news.usni.org/2018/09/24/eisenhower-carrier-maintenance-will-last-2019-tripling-length-expected-6-month-availability

9. For increase in Combatant Commander demand see:

Naval Operations Concept 2010. https://fas.org/irp/doddir/navy/noc2010.pdf

Excerpt: “Since 2007 the combatant commanders’

cumulative requests for naval forces have grown 29 percent for

CSGs, 76 percent for surface combatants, 86 percent for ARG/MEUs, and

53 percent for individually deployed amphibious ships.”

Vice Admiral Joseph Aucoin, USN (ret.), “It’s Not Just the Forward Deployed,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, April 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-04/its-not-just-forward-deployed

Excerpt:

“Between 2015 and 2017, naval operations in the Indo-Asia Pacific expanded dramatically both in direct response to national priorities and to ComPacFlt and Commander, U.S. Pacific Command (USPaCom). As a consequence of the increasing demand for and decreasing availability of C7F assets, readiness declined in CruDes forces. This was known both to commanders in FDNF and across the Navy. The GAO had reported to the Navy in 2015 that resources were not keeping pace with demand. Through 2016 and culminating in early 2017, my staff produced detailed data quantifying the increase in CruDes operational tasking and demonstrating the consequent decline in executed maintenance and training, which I sent directly to ComPacFlt. ComPacFlt agreed operational tasking threatened FDNF surface maintenance and training. Yet C7F received no substantive relief from tasking or additional resources.”

For increase in equipment casualty reports see: Government Accountability Office, “Navy Force Structure: Sustainable Plan and Comprehensive Assessment Needed to Mitigate Long-Term Risks to Ships Assigned to Overseas Homeports,” May 2015. https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670534.pdf#page=2

10. Admiral Bill Gortney and Admiral Harry Harris, USN, “Applied Readiness,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, October 2014. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-10/applied-readiness

11. Captain Dale Rielage, USN, “How We Lost the Great Pacific War,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-05/how-we-lost-great-pacific-war

Excerpt: “…we created a sustainment phase in the OFRP. This phase was designed to ensure that readiness did not “bathtub.” Each deployment cycle was envisioned to build on the previous iteration, ultimately creating the varsity-level performance the challenge demanded. The sustainment phase was also where we planned to keep surge forces, but it was never resourced. Ten years ago, the director of fleet maintenance for U.S. Fleet Forces referred to it publicly as a “sustainment opportunity” because there was no funding associated with it. The years of continuing resolutions, Budget Control Act restrictions, and maintenance deficits left the sustainment phase a shell of a concept.”

Megan Eckstein, “Navy Proves High Readiness Levels During Carrier’s Sustainment Phase Leads to Maintenance Savings Later,” U.S. Naval Institute News, August 3, 2017. https://news.usni.org/2017/08/03/navy-proves-high-readiness-levels-carriers-sustainment-phase-leads-maintenance-savings-later

Excerpt: Of course this high level of readiness had an upfront cost. [Admiral] Lindsey praised U.S. Fleet Forces Command commander Adm. Phil Davidson and his staff for the “maneuvers” it took to keep Eisenhower funded during the sustainment phase, saying “I never wanted for money that I needed to keep them at that high level. … That’s a testament to Adm. Davidson and his staff, his comptroller and everything.”

12. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Proves High Readiness Levels During Carrier’s Sustainment Phase Leads to Maintenance Savings Later,” U.S. Naval Institute News, August 3, 2017. https://news.usni.org/2017/08/03/navy-proves-high-readiness-levels-carriers-sustainment-phase-leads-maintenance-savings-later

13. Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command, “COMUSFLTFORCOM/COMPACFLT INSTRUCTION 3000.15A, Subject: Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” December 8, 2014. http://www.sabrewebhosting.com/elearning/supportfiles/pdfs/USFFC_CPF%20INST%203000_15A%20OFRP.pdf

14. “Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Readiness of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 114th Congress, September 10, 2015. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96239/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg96239.pdf

15. “Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Readiness of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 114th Congress, September 10, 2015. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96239/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg96239.pdf

Rear Admiral Bruce Lindsey and Lieutenant Commander Heather Quilenderino, “Operationalizing Optimized Fleet Response Plan – SITREP #1,” March 5, 2016. https://blog.usni.org/posts/2016/03/05/operationalizing-optimized-fleet-response-plan-sitrep-1

David Larter, “New Deployment Plan Faces Hurdles, Official Warns,” Navy Times, September 11, 2015. https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2015/09/11/new-deployment-plan-faces-hurdles-official-warns/

16. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Will Extend All DDGs to a 45-Year Service Life; ‘No Destroyer Left Behind’ Officials Say,” U.S. Naval Institute News, April 12, 2018. https://news.usni.org/2018/04/12/navy-will-extend-ddgs-45-year-service-life-no-destroyer-left-behind-officials-say

17. Bryan Clark and Jesse Sloman, Deploying Beyond Their Means: America’s Navy and Marine Corps at a Tipping Point, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, November 2015. https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA6174_(Deploying_Beyond_Their_Means)Final2-web.pdf

18. The story of the late 2015 carrier gap was picked up by outlets including Business Insider, U.S. Naval Institute News, CNN, Navy Times, Fox News, and Stars and Stripes.

19. For nature and benefits of forward presence operations see Navy strategy document: A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, 2015. https://www.navy.mil/local/maritime/150227-CS21R-Final.pdf

For nature of deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment see: Michael Gerson and Daniel Whiteneck, Deterrence and Influence: The Navy’s Role in Preventing War, Center for Naval Analyses, March 2009. https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/D0019315.A4.pdf

20. David Larter, “Is Secretary of Defense Mattis planning radical changes to how the Navy deploys?” Navy Times, May 2, 2018. https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2018/05/02/is-secretary-of-defense-mattis-planning-radical-changes-to-how-the-navy-deploys/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=ebb%2003.05.18&utm_term=Editorial%20-%20Early%20Bird%20Brief

21. Sam LaGrone, “U.S. Aircraft Carrier Deployments at 25 Year Low as Navy Struggles to Reset Force,” U.S. Naval Institute News, September 26, 2018. https://news.usni.org/2018/09/26/aircraft-carrier-deployments-25-year-low

Caveat: In the time period covered the Harry Truman strike group conducted operations in the Middle East but from the Eastern Mediterranean and not for the full duration of its deployment. Hence the distinction of describing naval presence as “deep” in Middle Eastern Waters, where typically carrier groups were deployed and maintained in the immediate vicinity of the Persian Gulf.

22. For U.S. Navy fleet size and ship counts see: US Ship Force Levels, 1886-Present, U.S. Navy History and Heritage Command. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/us-ship-force-levels.html#1986

To explain the difference between this point with the earlier comment on 40 percent shrinkage across 25 years, the Navy shrunk by half from 1990 to 2005, and where fleet size stabilized in the range of 270-280 ships around 2005. Open source data on deployment rates (as a defined by number of ships deployed per year) in the early 1990s was not immediately findable. However, in the early 1990s such as from 1990-1993 the fleet would drop in size by over 100 ships.

23. Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents, October 2017. https://s3.amazonaws.com/CHINFO/Comprehensive+Review_Final.pdf

24. “Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Readiness of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 114th Congress, September 10, 2015. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96239/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg96239.pdf

25. “Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Readiness of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 114th Congress, September 10, 2015. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96239/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg96239.pdf

See Also: “Aircraft Carrier – Presence and Surge Limitations and Expanding Power Projection Options,” Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces Meeting Jointly With Subcommittee on Readiness of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, 114th Congress, November 3, 2015. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg97498/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg97498.pdf

26. General Accounting Office, “Navy Carrier Battle Groups: The Structure and

Affordability of the Future Force,” February 1993.

27. Captain Wayne P. Hughes Jr., USN, “Naval Tactics and Their Influence on Strategy,” U.S. Naval War College Review, Volume 39, Number 1, Winter, 1986. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://cimsec.org/?p=37359&preview=true&httpsredir=1&article=4426&context=nwc-review

28. For reduced readiness standards see review conducted in aftermath of fatal 2017 collisions: Strategic Readiness Review 2017, http://s3.amazonaws.com/CHINFO/SRR+Final+12112017.pdf

Featured Image: Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Wash. (Aug. 14, 2003) USS Ohio (SSGN 726) is in dry dock undergoing a conversion from a Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN) to a Guided Missile Submarine (SSGN). (U.S. Navy file photo)