The following is part of Dead Ends Week at CIMSEC, where we pick apart past experiments and initiatives in the hopes of learning something from those that just didn’t quite pan out. See the rest of the posts here.

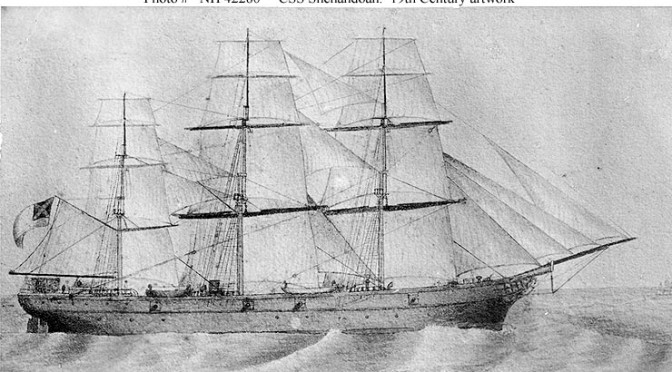

The history of the American Civil War has very little to say on the Confederate Navy. What it does say focuses on commerce raiding, mostly by the CSS Alabama, which is well-known enough to be in high school history texts. But others were out there, too, such as the CSS Shenandoah.

Shenandoah was most notable for raiding whalers in the Pacific for months after the war was over (the news travelled to them slowly), and its flag was thus the last to fly in the Confederacy’s name. But for our purposes here the ship’s propulsion, not its politics, are our concern.

As was common in the mid-19th century, Shenandoah had a hybrid sail/steam system. When winds were good, the crew hauled up sails, and when the wind ceased, they lit off the boiler. What made this ship unique was a retractable propeller that (theoretically, anyway) reduced drag and increased the ship’s speed while under sail.

Did it work any more effectively than opening (or was it closing?) the tailgate on a pickup truck helps fuel efficiency? Apparently sailors of the time thought it did. Whatever the answer, it soon became a moot point as sails disappeared entirely from merchant and military fleets around the world. The retractable propeller truly was a dead-end technology, designed to address what turned out to be only a transient problem. As other technologies and procedures developed, the propeller “hoist” became a solution without a problem to solve.

A note on sourcing: While I did find online references to the propeller hoist, this post is mostly based on my memory of “Last Flag Down,” an account of Shenandoah’s cruise by John Baldwin and Ron Powers – a book I cannot recommend highly enough. For a short description of the voyage, see the family history of the XO, Lt. Conway Whittle (near the bottom of the page).

Matt McLaughlin is a Navy Reserve lieutenant who never quite figured out the tailgate thing and ended up selling his pickup. His opinions do not represent the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense or his employer.