Navies are expensive. In the case of the U.S. Navy, they’re really expensive. A quick review of the SIPRI world defense spending database shows over 40 coastal nations whose entire defense budget would not buy a single Arleigh Burke-class destroyer at 2011-2012 prices.

Many of us who read and contribute to this forum are professionals in Maritime Security. As such, we tend to take for granted the importance of Navies and the positive role that Navies play in the international system. We have been conditioned to believe that Navies are worth the cost. But looking at the disparity in naval spending among maritime nations, it seems that not all nations share the same view of the relative dollar value of maritime security[i]. In an era of sharply declining defense budgets, and a maritime strategy that, while it places warfighting first, places heavy emphasis on the cooperative and international nature of maritime power, it’s worth asking whether navies are, in fact, cooperating in pursuit of a common goal. If so, what is that goal? The question, as suggested by the title of this forum, is: What exactly is “international maritime security?”

Security itself is a dependent concept. It’s not enough to say that a country is secure. It must be secure from something or someone. A reasonable working definition of maritime security might be “freedom from the risk of serious incursions against a nation’s sovereignty launched from the maritime domain, and from the risk of successful attack against a nation’s maritime interests.” In the absence of a specified threat, how much “security” a nation needs to defend against those incursions or attacks is speculative, at best. That makes the problem of defining international security more challenging—in order to be international, both the interests and the threat must be held in common by two or more nations. And, while an interest and threat held in common by just two nations might be international in the strictest sense of the word, the connotation of “international security” is of interests held widely throughout the international community.

Some naval missions seem to be inherently international and cooperative. Securing sea lines of communication is a great example. In the introduction to the U.S. maritime strategy, the authors gravely proclaim that, “Our Nation’s interests are best served by fostering a peaceful global system comprised of interdependent networks of trade, finance, information, law, people, and governance. We prosper because of this system of exchange among nations, yet recognize it is vulnerable to a range of disruptions that can produce cascading and harmful effects far from their sources.” Sure, maintaining the security of this global system serves our own interests, but we are quick to point out that in doing so, we are helping the interests of others, too.

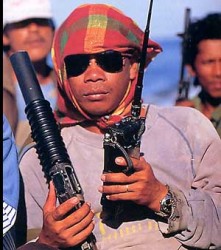

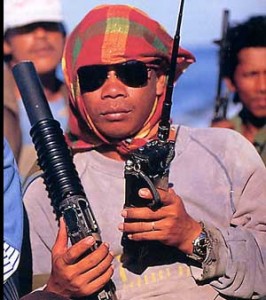

Although we in the U.S. Navy are proud of our role keeping the oceans safe for commerce, many other nations might reasonably ask, “safe from what?” Piracy is certainly one example, but does it justify the cost of a Navy? The global economic cost of maritime piracy has been estimated at $7 billion – $12 billion annually. Somali piracy in particular was more recently estimated at $7 billion annually. In contrast, the U.S. Navy budget alone is about $160 billion per year. With numbers like that, it’s difficult to make the economic case that Navies are a good answer to piracy, even when the human cost of piracy is factored in. About 3,800 seafarers were attacked and 35 killed by pirates in 2011. Sticking to water-related hazards, this pales in comparison to the 9,000 bathroom fatalities in the U.S. alone in 1999.

One answer to this critique has been to assert that other nations are free to define their maritime security narrowly because the U.S. defines maritime security broadly. According to this argument, the U.S. as a global maritime power must maintain open sea lanes all around the world; other nations, especially those whose trade ties are mostly regional, can hitch a free ride on our security at a fraction of the cost. Such a critique has an intuitive appeal, but it can’t be proved, since to do so would require a definitive measurement of the economic and human costs of the absence of U.S. efforts. Nevertheless, some version of the free rider argument is at the heart of many calls for increased defense burden sharing, and the desire to have other nations pick up at least a portion of the tab for “low-end” missions that are perceived to benefit all nations, rather than serving strictly U.S. interests.

The parable of the tragedy of the commons offers an interesting perspective on free-riding, burden sharing, and international maritime security. Writing in 1968 in the journal Science, biologist Garrett Hardin suggested that when there is a public resource—a commons—which is limited and diminished by use, but can be used by individuals without marginal usage cost, each individual will tend to increase their use (grazing herds in his example) until the resource itself is exhausted. According to this view, which has great traction in economic circles, each person expects to derive greater benefit from increasing their own use rather than showing restraint, since they expect their neighbors to likewise show no such restraint. If the commons are going to be depleted anyway, why not get mine? It is in such a situation that free riding becomes both possible and problematic. When a wealthy neighbor takes the time and money to fence off parts of the pasture and let it recover, everyone benefits; however the wealthy neighbor alone bears the cost, not only of the restoration efforts, but also of the outrage from their fellow cattlemen that they violated the concept of the commons by fencing it off. The wealthy neighbor does have some recourse: to begin with, because he is caring for the resource itself, rather than just his own herd, he has a legitimate moral claim against his fellow cattlemen; depending on his own pain threshold, he may try to make good on that claim by withholding his public service (whether in the fenced off area or more widely) until his neighbors begin to pay their share. Pursuing that course, however, comes with a risk—if he’s not willing to bear the pain of seeing the commons fall into disrepair, his neighbors may effectively call his bluff and he will go back to caring for the public good out of his own pocket. To many, this seems an apt metaphor for the predicament of the U.S. in security affairs.

The oceans are often described as a “maritime commons;” is there a corresponding “tragedy of the maritime commons?” Yes and no. One of the key aspects of Hardin’s metaphor is that the resource itself is limited and diminished by use. Global commerce has no limiting feature, and while the sea lanes may become more crowded, they are no less available if more trade takes to the seas. Since the resource itself is not diminished or threatened by use, U.S. efforts to secure the sea lanes are not really efforts to secure the commons, but to protect U.S. interests in the form of trade. While other nations may benefit from this, we would do it whether they benefited or not. In such a case, the international aspect of our maritime security interest is purely coincidental. We may be happy or unhappy with the level of help from other nations, but we have no leverage to encourage them to give more or less.

Fisheries protection, on the other hand, is an example of an international maritime security interest where the tragedy of the commons has been very real and very costly. According to a study funded jointly by the UK government and the Pew Charitable trusts, illegal fishing costs between $10 and $23 billion annually. These figures, comparable to piracy in scope, often have an immediate impact on the lives of local populations, and at least one study has suggested that fishery depletion from illegal fishing is a contributing cause of maritime piracy.

Missions like fisheries protection aren’t terribly sexy. In the U.S., we have normally assigned these missions to NOAA or Coast Guard personnel. For many other nations, however, this is a central Navy mission.

Seeking common ground in international maritime security is good practice, not only from an economic perspective, but also because it increases our understanding of regional partners and problems, potentially affording the opportunity to stop an emerging crisis before it ever develops. But our definition of international maritime security must go further than, “other navies do the same things we do, and help foot the bill.” If the USN is to meaningfully pursue international maritime security we must seek out areas where we truly share common interests, common threats, and common resources.

CDR Doyle Hodges is a Surface Warfare Officer in the U.S. Navy. He has commanded a rescue and salvage ship in the Pacific and a destroyer in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Middle East. He is the Chairman of the U.S. Naval Academy’s Seamanship and Navigation Department. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, or the U.S. Naval Academy.

[i] For more accurate comparison of the relative value each country places on security, it is more useful to compare defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP, as found here than total outlay. While the CIA does not break out naval expenditures separately, total defense spending serves as a useful, though not perfect, proxy.