Erik Larson’s Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania. Crown. 448pp. $28.00

(This review is an edited and expanded version, originally posted on Foreign Policy’s “Best Defense.”)

In grade school, I remember watching an old movie about the sinking of the Titanic. It might have been Roy Ward Baker’s A Night To Remember. But whatever it was, the sinking of the Titanic was always in the front of my mind when someone mentioned the loss of a large passenger vessel. The attack on the Lusitania, however, was a footnote in our history books; maybe it made half the page — if that. Now, 100 years later, the First World War is almost ignored by Americans. David Frum, over at The Atlantic magazine, has a great article about the lack of US interest in the war. Frum says that “The United States lost some 115,000 soldiers in the First World War, more than in Vietnam, Korea, and all other post-1945 conflicts combined. Yet the war’s impress on the American mind — once seemingly so deep and indelible — has faded. The war men once called ‘the Great’ has receded almost beyond memory in this country that did so much to win it.”

In grade school, I remember watching an old movie about the sinking of the Titanic. It might have been Roy Ward Baker’s A Night To Remember. But whatever it was, the sinking of the Titanic was always in the front of my mind when someone mentioned the loss of a large passenger vessel. The attack on the Lusitania, however, was a footnote in our history books; maybe it made half the page — if that. Now, 100 years later, the First World War is almost ignored by Americans. David Frum, over at The Atlantic magazine, has a great article about the lack of US interest in the war. Frum says that “The United States lost some 115,000 soldiers in the First World War, more than in Vietnam, Korea, and all other post-1945 conflicts combined. Yet the war’s impress on the American mind — once seemingly so deep and indelible — has faded. The war men once called ‘the Great’ has receded almost beyond memory in this country that did so much to win it.”

He’s probably right.

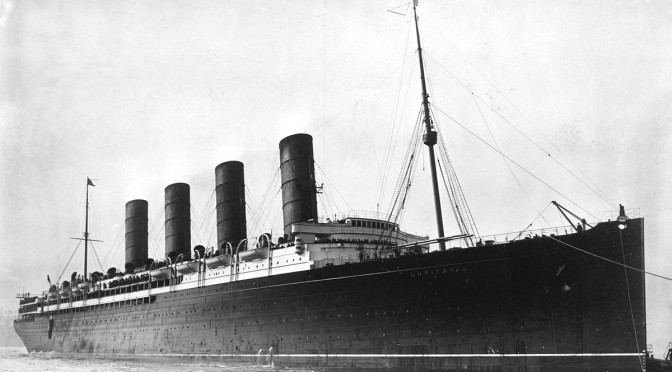

Fortunately, there are still writers out there willing to tell fascinating stories about WWI, reminding us of its importance. The sinking of the Lusitania is one of those great stories. Erik Larson, in his new book, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, tells a gripping account of that passenger ship’s last voyage and its unfortunate demise in cold waters off the coast of Ireland on 7 May 1915.

If you’ve read some of his other stuff — In the Garden of Beasts or The Devil in the White City — you know that Larson is great at writing narrative nonfiction. In a recent interview in The New York Times, Larson credits writers John McPhee and David McCullough as some of the best writers in narrative nonfiction working today. Larson’s Dead Wake, however, is on par with McCullough’s Mornings on Horseback or McPhee’s Pieces of the Frame or Coming Into the Country. Larson’s strength lies in the fact that we all know how the story ends, but he still makes you want to turn the pages, and turn them quickly.

What makes the story so compelling, is that Larson takes a few main characters — the Lusitania’s Captain William Thomas Turner, President Woodrow Wilson, U-boat Captain Walther Schweiger, Boston bookseller Charles Lauriat, architect Theodate Pope, and a few minor ones — and weaves them together towards the inevitable and tragic conclusion. This style of narrative pacing — shifting perspectives and characters — has an attractive cinematic quality that works quite well here.

And then there’s his research. The number of details and anecdotes that he has managed to cobble together are fascinating in themselves. Here is just a few of the more interesting ones:

- Boston bookseller Charles Lauriat was carrying Charles Dickens’s personal copy of A Christmas Carol and over 100 drawings done by William Makepeace Thackeray.

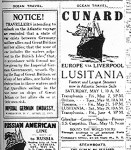

- There were published warnings from the German embassy prior to the Lusitania setting sail that the “Lusitania is doomed…do not sail her.” Only two passengers cancelled their trip due to the warning.

- Elbert Hubbard, author of A Message to Garcia, was on board for the crossing. And the most famous passenger, Alfred Vanderbilt, son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, paid just over $1000.00 for two rooms: one for his valet and one for himself. Or “equivalent to over $22,000 in today’s dollars.”

- Larson has a great chapter on the life aboard German U-boats in WWI. From descriptions of the putrid smell inside the boats to problems with the single toilet, and finally to German torpedoes which, he says, failed 60% of the time.

- U-20 had one dog onboard; Larson says that they had up to six at one point, four of which were puppies.

- American first class passengers that had died and whose bodies were recovered were embalmed on behalf of the U.S. government. The others…sealed inside lead coffins to “…be returned to America whenever desired.”

Another interesting thing is neither Churchill nor Wilson come off well here. Wilson, recently having lost his wife from kidney failure, comes across as love sick, pining for Edith Galt (who would end up running the White House after Wilson’s stroke in 1919). Wilson’s recovery from depression following his wife’s death and then his courtship of Galt seemed to consume him entirely. Meanwhile, almost daily, the massive armies in Europe reached new levels of death and suffering. Saying that Wilson was distracted would probably be a supreme understatement.

As for Churchill, well, he tries to lay the blame for the Lusitania’s sinking at the feet of Captain Turner. Yet Churchill and eight other senior British government officials, Larson says, had access to captured radio transmissions between German naval headquarters and underway U-boats. They knew U-20 was operating in waters that the Lusitania had to cross to get to Liverpool. Churchill knew that Turner was not responsible for the loss of the Lusitania, for there was little that Turner could do. British code breaking was so good, that a number of messages that were intercepted by “Room 40” — the secret listening station in London — even gave British leadership a good understanding of the personalities of individual U-boat captains.

This spring it will be 100 years since Cunard’s great ocean liner — and briefly the largest in the world — went down, killing over 1,000 passengers, 128 of them Americans. America wouldn’t join the war until two years later — in 1917 — after the infamous Zimmerman telegram was uncovered by British cryptographers. Still, the sinking of the Lusitania is, for many of us, an image in our minds of the first dead Americans of that Great War. And in some ways the sinking of that ship was the beginning of the inevitable: the US would join the war effort, it was simply a matter of time.

You’ll have to pick up the book and see for yourself what happens to Captain Turner, Captain Schweiger, Vanderbilt, and many others. Or if Charles Lauriat was able to save the Dickens book and Thackeray drawings. It’s worth finding out.

You’ll have to pick up the book and see for yourself what happens to Captain Turner, Captain Schweiger, Vanderbilt, and many others. Or if Charles Lauriat was able to save the Dickens book and Thackeray drawings. It’s worth finding out.

LCDR Christopher Nelson, USN, is a career intelligence officer and recent graduate of the US Naval War College and the Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI.