By Christian H. Heller

Introduction

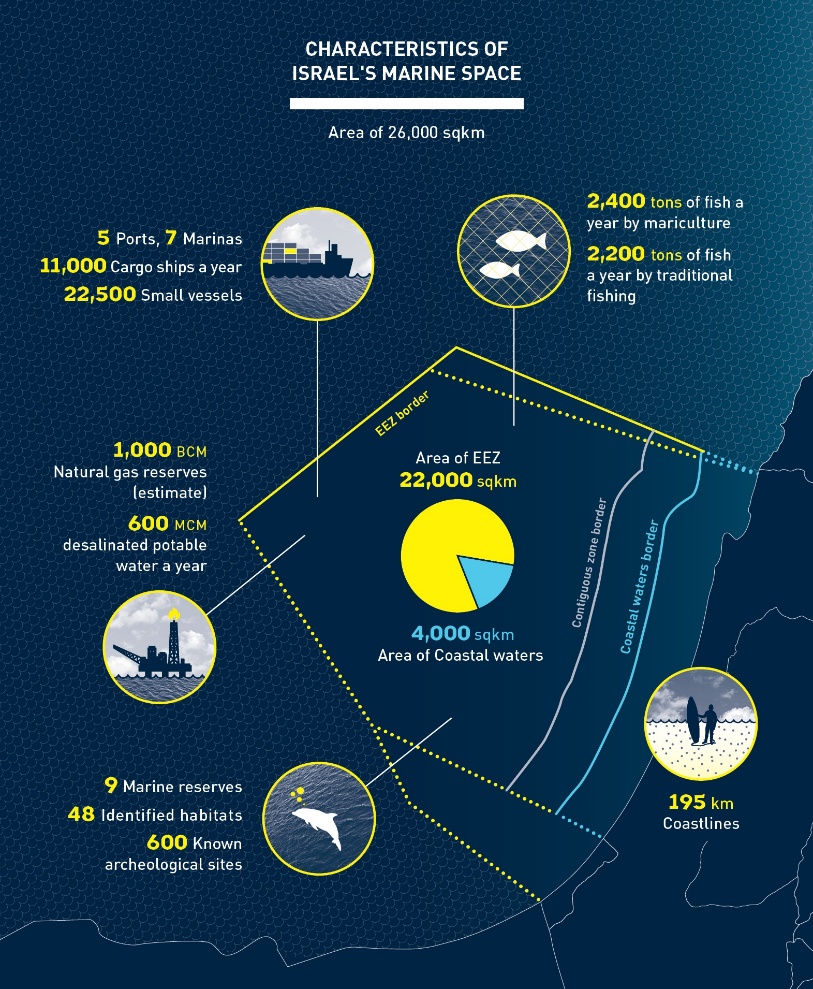

The 1973 Yom Kippur War shocked Israel and the world. Israeli Defense Force (IDF) complacency led to days of panic as Egyptian and Syrian forces threatened the very existence of Israel and triggered the potential “demise of the ‘third temple.'”1 Emergency American aid supported the Jewish defenders and averted a possible superpower confrontation reminiscent of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Politically, the war reset a diplomatic stalemate between the Arabs and Israel and led to the negotiations at the Camp David summit. Militarily, the naval battles of the Yom Kippur War played almost no part in its outcome. They did, however, initiate a technological and tactical maritime revolution. The battles proved the effectiveness of missile and anti-missile systems to control the seas, and ushered in the missile age of naval warfare.

Breakout of War

The origins of the Yom Kippur War lie in the Arab humiliation during the previous war with Israel, nearly six years earlier. The overwhelming Israeli victory in the 1967 Six-Day War created a political stalemate in which both sides were unwilling to negotiate from their resultant positions.2 Israel occupied the Golan Heights from Syria and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Arabs knew their territory could not be recaptured via direct conflict.3 The new territory gave Israel the defensible borders and strategic depth it previously lacked and it refused to give them up.4 In Egypt, Anwar Sadat faced domestic unrest from a serious lack of state revenue due to the loss of the Suez Canal.5 The Egyptian population demanded “redemption” for their humiliation in the 1967 war.6

Egypt carefully planned for a limited war to achieve modest gains and reset the balance at the negotiating table. The main barrier to their plans was the Israeli Air Force (IAF). Most of the Egyptian Air Force (EAF) was destroyed on a single day in 1967 and Egypt’s air defenses were incapable of defending against the advanced Israeli planes.7 With the help of Soviet surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems like the SA-2, SA-3, and SA-6, Egypt created a “layered anti-aircraft missile defense force” and increased its anti-aircraft (AA) missile force fourfold.8 The AA umbrella could both deter Israeli preemptive strikes and protect Egyptian forces while crossing the Suez Canal and invading the Sinai.9 Egypt also obtained new anti-tank weapons like Sagger missiles and armored vehicles to mitigate Israel’s superiority in armor assets and neutralize their counterattack capabilities in the Sinai.10 Together, with an impressive misinformation campaign, Soviet support for resupplies, and close coordination with Syria, the Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a successful surprise invasion of Israel on the night of 6 October 1973.

Israel and its military were caught unprepared for the attack. Their leaders believed, “there was no chance for an Egyptian victory, thus no rational reason to resort to force.”11 Without a capable air force to negate the IAF’s advantage, leaders in Tel Aviv assumed they would be free from Egyptian military action until at least 1974.12 The night of 8 October, during which Egyptian anti-tank missiles destroyed an entire Israeli armor division in the Sinai, was one of the worst situations Israel has ever faced. Some records indicate that nuclear weapons were prepared, and on 9 October Prime Minister Golda Meir intended to fly to Washington, D.C. to personally request American help.13,14 American military aid flowed into Tel Aviv to avert an international crisis and potential nuclear war, and within a few days Israel again had the upper-hand in the conflict.15

Israeli Naval Preparations

The Israeli Navy was the only service prepared to fight and win the war from its initiation. While 1967 was an overwhelming victory for the army and air force, the navy found itself outgunned by Egypt’s Soviet-built missile boats. Egypt sank the Israeli destroyer Eilat with anti-ship missiles from its small, maneuverable, and heavily-armed missile boats. Israel’s navy traditionally had an inferior status domestically compared to the other military services and the deaths of 47 sailors on the Eilat reinforced that public opinion.16 The attack had a “traumatic effect” on the Israeli Navy whose leaders set about enacting immediate reforms.17

Events on the other side of the Middle East reinforced Israel’s desire to improve its navy. Soviet missile boat technology demonstrated promise during the India-Pakistan War of 1971. The Indian Navy purchased Osa-class boats from the Soviet Union and trained with them at the port of Okha, near the Pakistani port of Karachi.18 The Soviet Navy led the world in littoral small craft development at the time. In 1975, the Soviet Navy had more “small combat craft” than the combined total throughout the rest of the world.19 The 130-ft Osa-class was the most well-known of the littoral ships. A standard vessel carried four Styx missile launchers and cruised at a top speed of 32 knots.20

The development of an anti-ship cruise missile became a Soviet goal after World War II. The U.S. Navy on the other hand, led by aviators with knowledge of bombing and torpedoes, believed their weapons to be the perfect anti-ship weapon. In contrast, the Soviet Navy developed multiple versions of cruise missiles to compensate for its lack of naval aviation.21

The missile boats’ speed, agility, and striking capability in the littoral waters along the two nations meant the squadron could reach Pakistani naval targets at Karachi immediately upon the outbreak of hostilities. On 4 December, Indian missiles sank one Pakistani destroyer, one Pakistani minesweeper, one merchant ship, and damaged some oil storage facilities. Due to a possible aircraft counterattack, the Indian missile boats withdrew. While Indian naval leaders welcomed the victory, questions emerged about pressing the offensive and taking advantage of weak Pakistani defenses in the region.22 The Indian Navy launched a second strike four days later that destroyed another oil tanker and damaged two commercial tankers.23 The attacks demonstrated the possibilities of missile technology for offensive strikes and controlling an enemy’s naval capabilities as the Pakistani Navy restricted its movements outside of the Karachi harbor after the Indian victories.

The Israeli Navy took notice of the India-Pakistan conflict and decided that small boats with advanced missiles had a greater advantage over large ships like destroyers and frigates in the littoral waters of the Eastern Mediterranean and Red Sea.24 The increase in Israeli territory with the capture of the Sinai Peninsula in 1967 meant more coastline for the navy to protect, and a blue water navy composed of ocean going vessels was unnecessary when their main operating area was the littorals.25

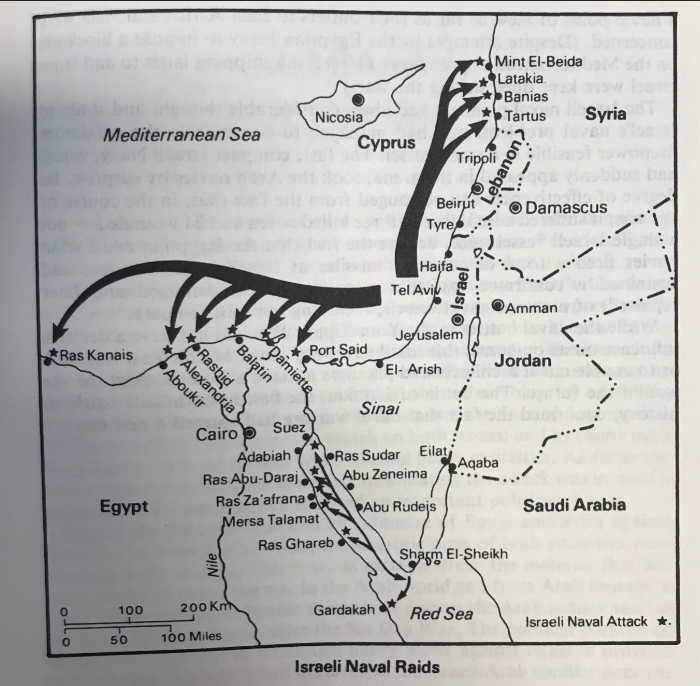

Israeli missile boat procurement began in 1962 when Egypt and Syria obtained Soviet missile boats but accelerated drastically after 1967.26 By the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, the Israeli Navy consisted of fourteen Sa’ar-class missile boats.27 It was the first non-Soviet allied nation in the world to enter the anti-ship missile age.28 They faced significant numbers of enemy vessels. Egypt’s surface-craft consisted of twelve Osa-class missile boats, twenty-six torpedo boats, three destroyers, two frigates and various other vessels.29 Syria’s navy consisted of three Osa– and six older Komar-class missile boats, eleven torpedo boats, and two minesweepers.30

The small size of the missile boats was intended to minimize their target signature and add to the ships’ survivability, but raised questions about their potential firepower. The sinking of a fishing vessel by the Egyptians with a Soviet-built Styx missile in 1967 showcased both the ships’ capabilities and the threat to the Israeli Navy. The Styx missiles of Syria and Egypt also had a range of 25 nautical miles compared to the 12 nautical mile range of Israel’s Gabriel missiles.31 Despite Israel’s new ships, training, and preparations, its navy was still “out-ranged in missiles and outnumbered more than two to one” at the beginning of the conflict.32 In response, Israel accelerated its development of advanced electronic countermeasures to provide a greater defensive buffer for its new fleet.33 Israeli naval leaders also war gamed and experimented with new tactics to add additional defensive capabilities to their ships.34

Operationally, Israeli naval commanders learned from the lessons of the previous wars about limited flexibility and unclear tasking. They assigned three objectives to the navy in the Mediterranean: coastal defense, the elimination of the threat from Arab missile boats, and to support ground troops.35 The navy decided their offensive strategy would focus on the enemy missile boats.36 An active pursuit of the enemy’s naval assets would secondarily support the other two objectives.

The naval battles of the Yom Kippur War were remarkable for two historic developments. They were the first battles in history in which both combatants possessed ship-to-ship missiles, as well as the first time electronic countermeasures were used to defend against missile attacks.37 Two battles in particular highlight these historic changes in naval warfare: Latakia and Baltim.

The Battles

On the night of 6 October, 1973, at the outset of the war, a flotilla of five Israeli missile boats cruised off the coast of Syria attempting to draw the Syrian Navy into battle.38 They identified a Syrian torpedo boat, pursued it east towards shore, and sunk it. While sailing south along the coast opposite Latakia, a main Syrian harbor and naval base, the INS Reshef sank a Syrian minesweeper. The flotilla then identified three Syrian missile boats and deduced that the torpedo boat and minesweeper were naval decoys or observation posts.39 The Syrian ships launched eight Styx missiles at the Israeli squadron, but each was defeated with chaff launches which pulled the Styx targeting system away from the Israeli ships.40

The Israeli vessels advanced quickly and “sandwiched” the Syrian boats between them.41 In total, the Israeli flotilla launched 11 Gabriel missiles, six of which hit their targets.42 In only 25 minutes the navy sank three Syrian vessels. Israel resoundingly won the first naval missile battle in history with no casualties.43 Five Syrian ships were sunk and the Israeli Navy’s offensive and defensive developments tentatively proved themselves in battle.

Two days later on the night of 8 October, six Israeli vessels cruised towards Egypt in two columns after the devastating defeat of Israel’s tank-led counterattack in the Sinai.44 The squadron’s initial intent was to target military facilities just west of the Suez Canal.45 Four Egyptian boats attacked at midnight. The Egyptian Osa missile boats fired 16 missiles near their maximum range, then turned and ran. The Israeli ships shot twelve Gabriel missiles while pursuing. Six hit their targets and three Egyptian ships sank.46

The one-sided results from the battles frightened the Egyptian and Syrian leaders who restricted their navies to the waters nearest their harbors, just as Pakistan did two years earlier. The war involved subsequent smaller battles such as the Second Battle of Latakia. However, these battles involved Arab navies shooting their missiles from afar while relying on protection from merchant ships or coastal defenses.47 Fighting on land continued for almost three more weeks, but the war for the littorals was over.

Tactical and Technical Developments

Israel developed tactics and technology specifically suited to its own needs. The small state knew who its enemy was and where its future conflicts would take place. The combination of domestically produced ships, new missiles, and original tactics was “one of the clearest cases of Israel’s tailoring its forces to those of the Arabs.”48 It developed ships and crews able to conduct advanced scouting activities, execute effective command and control, and employ overbearing firepower on its enemy. Each of these advancements helped the Israeli Navy overcome major deficits in numbers and range. The combination of surprise, initiative, and a boldness to use new capabilities became hallmarks of the Israeli littoral squadrons.49

The Sa’ar-class vessels combined the “maximum firepower possible” in a small, fast vessel perfectly suited for Eastern Mediterranean.50 Israel’s Gabriel missiles destroyed eight Arab ships, including six of their seven missile boats, despite their short range.51 The concentration of firepower onboard the Sa’ar was key to victory. During Latakia, the Israeli ships possessed 26 missiles each compared to Syria’s eight. In Baltim, the Israeli ships carried as many as 34 missiles compared to 16 on each Egyptian boat.52 Additionally, the Arabs made themselves easy to identify and target by keeping their radars turned on and talking frequently over open radio.53

Israel’s experimental tactics were simple. The Israeli boats turned toward the enemy to face them head on and charge at full speed to minimize their target profile and launched chaff decoys early to entice the enemy to launch their missiles at the furthest range. When the Arabs shot their missiles at the full 25 nautical miles, the Israelis were gifted with the maximum time possible to detect and avoid them while in flight.54 Then, using electronic countermeasures and more chaff, the Israeli boats could close with the enemy while evading the incoming missiles until within range of the Gabriels.55

Israeli defensive advancements achieved similar success. The Israeli Navy had no aircraft for reconnaissance and target identification but relied on electronic detection systems which could track the enemy’s radar without betraying their own position.56 The “multiple tricks” of long-range chaff, electronic jammers, high-speed maneuvers, radar-absorbing coating on the bows of the ships, and close-range chaff saved the Israeli fleet.57,58 The Egyptian and Syrian navies shot 52 missiles at the Israeli ships, and all of them missed.59

Israel also maximized its littoral geography and short lines of communications for speedy re-fueling and re-supply. The Israeli sustainment system was so efficient for the navy that it operationally turned a fleet of 14 ships into 24.60

Missile developments emerged on land during the war as well, adding to the impact which these new technologies could have on warfare. The success of “one of the densest missile walls in the world,” built by Soviet anti-aircraft missiles, demonstrated that control over the air could originate from below.61 Over 100 IAF aircraft were destroyed by Soviet-built SAM systems.62 The Egyptian army’s new anti-tank equipment paid off when the Israeli armored counterattack was “simply destroyed.”63 Within 24 hours of the invasion, the Israeli defenders in the Sinai lost over two-thirds of their 270 tanks to Egyptian anti-tank weapons.64 The world was paying attention, and these developments reshaped modern warfare.

The Impact

Due to years of technical and tactical preparation combined with thousands of simulations and wargames, the Israeli Navy was the country’s only service ready to fight and win on October 6, 1973.65 Israeli naval leaders had instituted and carried-out a ten-year plan to directly tailor their naval capabilities to take advantage of the Egyptian and Syrian weaknesses.66 In the end the naval battles of the Yom Kippur War had no significance toward the outcome of the conflict, but its military impact was substantial and long-lasting.

Israeli successes in offensive and defensive missile technology marked the beginning of the missile age for naval warfare, especially for littoral combat power. The size of the ship and its guns mattered far less than its missiles and their accuracy. Defensive countermeasures like chaff, electronic jamming, and radar-absorbent paint became necessities as ships now acted under the premise of first-to-see, first-to-kill. Such offensive and defensive measures are mandatory in today’s naval operating spaces where anti-access/area-denial strategies and over-the-horizon systems are prolific, especially with regard to the littorals and close operating areas of the Pacific and Middle Eastern theaters.

Just as naval artillery transitioned from cannons to breech-loading artillery and fleet structure shifted from battleships to aircraft carriers, the Yom Kippur War ushered in the age of the missile, the missile boat, and modern littoral naval combat. Limited American experimentation with cruise missiles morphed into a complete fervor following the Yom Kippur War. The Harpoon missile research program, initiated in 1969, escalated with the U.S. Navy’s purchase of 150 missiles in 1974. The U.S. Navy formalized production in 1975. By 1979, 1,000 Harpoons had been delivered to the Navy with more in waiting.67

There is no modern definition for a missile boat, but most tend to be less than 1,000 tons (for reference, the Freedom-class Littoral Combat Ship weighs in at 3,500 tons), shorter than 90 meters, sails at a high speed, and carries an armament of cruise missiles and search radar to find targets.68 Their purpose is to be a cheap, mobile launching platform that achieves a high return-on-investment through the destruction of much larger, more expensive enemy ships. The capability—potential and realized—of a small fishing-boat sized warship to sink larger vessels like frigates, corvettes, tankers, or possibly aircraft carriers, has allowed smaller nations to field formidable naval threats in their home waters.

Most naval professionals are at least loosely familiar with the threat from Iranian fast attack craft in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz. This technology, combined with geographic chokepoints, coastal geography, numerous staging areas, and defensive capabilities, permits Iran to pose a heavyweight threat with a lightweight force.69 Iran’s exploitation of its littoral advantages and unique offensive and defensive capabilities allows it to apply a doctrine of asymmetric naval warfare which could produce, “highly destabilizing and surprising results.”70

Regardless of naming convention or location, fast, lightweight, heavily armed ships will remain an enticing option for navies around the world, especially those without the finances to deploy blue-water fleets or with naturally supportive geography. The Israeli Navy proved the efficacy of such a strategy in 1973 when a few insignificant naval battles changed naval warfare forever.

Christian Heller is an active duty intelligence officer in the United States Marine Corps. He is an honors graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Oxford University, and was a Rhodes Scholar.

References

[1] Avner Cohen, “When Israel Stepped Back From the Brink”, The New York Times, 3 October 2013, Accessed online at https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/04/opinion/when-israel-stepped-back-from-the-brink.html

[2] Tomis Kapitan, “Arab-Israeli Wars”, Encyclopedia of War and Ethics, edited by Donald A. Wells (Greenwood, 1996), 21

[3] David T. Buckwalter, “The 1973 Arab-Israeli War”, Case Studies in Policy Making & Implementation from Naval War College, 119, http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/navy/pmi/

[4] Ibid., 120

[5] Ibid.

[6] Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1991), 418

[7] Mohamed Kadry Said, “Layered Defense, Layered Attack: The Missile Race in the Middle East”, The Nonproliferation Review, Summer 2002, 37

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Chaim Herzog, The Arab-Israeli Wars (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 229

[11] Buckwalter, “The 1973,” 130

[12] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 227

[13] Elizabeth Stephens, “The Yom Kippur War”, History Today 58 is. 10 (October 2008): 5

[14] Buckwalter, “The 1973,” 130

[15] Stephens, “The Yom,” 5-8

[16] Adam B. Green, “The Israeli Navy’s Application of Operational Art in the Yom Kippur War: A Study in Operational Design”, Naval War College, 12 May, 2017, 1-4

[17] Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), “The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: Overview and Analysis of the Conflict”, September 1975, 113, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/1975-09-01A.pdf

[18] Vice Admiral GM Hiranandani, Transition to Triumph, Excerpt, 1 November 2017, Accessed at http://www.indiandefencereview.com/interviews/1971-war-the-first-missile-attack-on-karachi/

[19] “A Look at the Soviet Navy”, All Hands, September 1975, 11, Accessed online at http://www.navy.mil/ah_online/archpdf/ah197509.pdf

[20] Ibib.

[21] Kenneth P. Werrell, The Evolution of the Cruise Missile (Alabama: Air University Press, 1985), 150

[22] Hiranandani

[23] “Trident, Grandslam and Python: Attacks on Karachi”, Bharat Rakshak, 7 July 2004, Accessed at https://web.archive.org/web/20141119181622/http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/History/1971War/44-Attacks-On-Karachi.html?start=1

[24] Ibid.

[25] Green, “The Israeli,” 3

[26] Ibid.

[27] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 311

[28] Green, “The Israeli,” 4

[29] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 311

[30] Ibid.

[31] John C. Schulte, “An Analysis of the historical effectiveness of anti-ship cruise missiles in littoral warfare”, Naval Post-Graduate School, September 1994, 5

[32] Green, “The Israeli,” 1

[33] Green, “The Israeli,” 4

[34] CIA, “The 1973,” 113-114

[35] Green, “The Israeli,” 8

[36] Ibid.

[37] Yao Ming Tiah, “An Analysis of small navy tactics using a modified Hughes’ Salvo Model”, Naval Post-Graduate School, March 2007, 52

[38]Tiah, “An Analysis,” 52

[39] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 311-312

[40] Schulte, “An Analysis,” 5

[41] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 312

[42] Schulte, “An Analysis,” 5

[43] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 312

[44] Tiah, “An Analysis,” 53

[45] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 312

[46] Schulte, “An Analysis,” 6

[47] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 312-313

[48] CIA, “The 1973,” 113

[49] Tiah, “An Analysis,” xxi

[50] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 314

[51] Tiah, “An Analysis,” 52

[52] Ibid., 54

[53] CIA, “The 1973,” 114

[54] Ibid.

[55] Jonathan F. Solomon, “Maritime Deception and Concealment: Concepts for Defeating Wide-Area Oceanic Surveillance-Reconnaissance-Strike Networks”, Naval War College Review 66, no. 4, 2013, 13

[56] Tiah, “An Analysis,”, 54

[57] Solomon, “Maritime Deception,” 13 3

[58] CIA, “The 1973,” 113

[59] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli, 314

[60] Green, “The Israeli,” 11

[61] Herzog, The Arab-Israeli,, 227

[62] Robert S. Bolia, “Overreliance on Technology in Warfare: The Yom Kippur War as a Case Study,” Parameters, Summer 2004, 53

[63] Charles F. Doroski, “The Fourth Arab-Israeli War: A Clausewitzian Victory for Egypt in Seventy-Three?” Naval War College, 16 May 1995, 10

[64] Buckwalter, “The 1973,” 126

[65] Green, “The Israeli,” 8

[66] CIA, “The 1973,” 114

[67] Werrell, The Evolution, 151

[68] “Analysis: Are Missile Boats Still Relevant in Modern Warfare”, Defencyclopedia, 17 November 2016, Accessed online at https://defencyclopedia.com/2016/11/17/analysis-are-missile-boats-still-relevant-in-modern-warfare/

[69] Fariborz Haghshenass, “Iran’s Asymmetric Naval Warfare”, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Focus #87, September 2008, 7-11

[70] Haghsenass, 25

Featured Image: Saar3 missile boat. (Wikimedia Commons)