By Brigadier General John M. Waweru (Ret.), IMO Consultant

Introduction

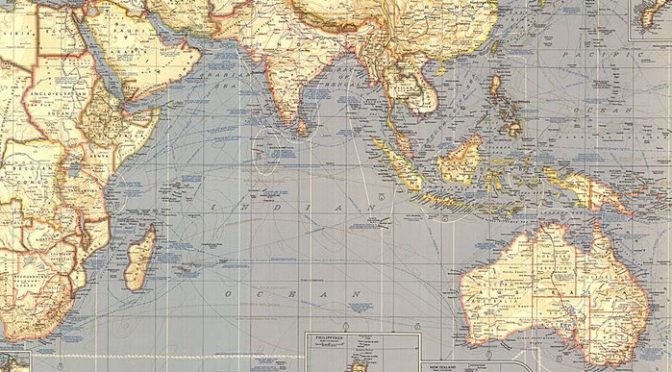

The Western Indian Ocean Region (WIO) holds substantial geopolitical and economic importance due to its location along vital international sea lanes, facilitating maritime trade between Asia, Africa, and Europe. Approximately 80% of the world’s seaborne oil trade transits through these waters, underscoring their global relevance.1 Key chokepoints such as the Bab el-Mandeb Strait enhance this strategic importance. However, the region faces escalating maritime threats, including kinetic attacks on shipping, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, illicit trafficking, piracy, and terrorism.2 These challenges compromise economic stability and pose broader threats to regional and global security.

Salient Threats to Regional Maritime Security

Kinetic Attacks on Merchant Shipping in the Red Sea

Kinetic attacks in the Red Sea, often attributed to the ongoing conflict in Yemen, have significantly threatened global maritime trade. Armed groups such as the Houthis have targeted commercial vessels with missiles and drones, endangering crew safety and destabilizing global energy supplies.3 These incidents have increased shipping insurance premiums and triggered route deviations, inflating global trade costs.

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing (IUUF)

IUU fishing severely affects economic and ecological systems in the WIO. Coastal African states—including Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia, and Mozambique—report annual losses in the billions due to illegal fishing practices.4 These activities deplete marine stocks, disrupt food security, and exacerbate unemployment and migration pressures. The environmental degradation caused by IUUF also threatens long-term sustainability of the blue economy.5

Illicit Trafficking

The WIO is a conduit for various forms of illicit trafficking, including narcotics, weapons, human smuggling, and wildlife trafficking. The region’s porous maritime borders allow transnational criminal networks to flourish, undermining governance and fueling corruption.6 Illicit trafficking also enables the financing of insurgencies and extremist movements, further destabilizing coastal and inland regions.7

Terrorism and Piracy

Although Somali piracy has declined since its 2011 peak, emerging incidents suggest a possible resurgence.8 Moreover, terrorist groups have reportedly leveraged maritime spaces for logistical support, recruitment, and attacks—especially in regions around Lamu and the Gulf of Aden.9 The fusion of terrorism and piracy heightens risk for both commercial vessels and regional maritime governance.

Comparative Salience and Extended Impact

Kinetic attacks and IUU fishing are particularly impactful due to their economic consequences and global spillover effects. Strategic chokepoints such as the Bab el-Mandeb amplify the risks of kinetic threats, while IUUF contributes directly to ecosystem collapse, economic displacement, and regional instability.10 These phenomena also contribute to migration crises, fuel maritime militarization, and alter trade patterns—creating ripple effects in Europe, Asia, and beyond.11

Strategic Response and Mitigation Approaches

Direct Responses

IUU fishing can be curtailed through capacity-building, improved monitoring, and the use of satellite surveillance technology. Strengthening legal frameworks and investing in regional fisheries governance are also critical steps.12

Multilateral Approaches

Due to their cross-border nature, threats like piracy and terrorism necessitate collective action. Regional cooperation through the Djibouti Code of Conduct and global coalitions like the Combined Maritime Forces has improved information sharing and joint patrol capabilities.13 Diplomatic solutions addressing political drivers of conflict—especially in Yemen and Somalia—are equally crucial.

Threat Mitigation

Illicit trafficking is best addressed through enhanced maritime domain awareness, harmonized regional legislation, and anti-corruption initiatives. Developmental interventions targeting root causes—such as poverty, unemployment, and institutional weakness—are essential for long-term security.14

Conclusion

The Western Indian Ocean Region remains a critical hub for international trade, energy transport, and ecological resources. Yet it faces multifaceted maritime security threats that demand urgent and coordinated responses. A balanced strategy combining direct enforcement, multilateral diplomacy, and developmental initiatives is essential. Regional stakeholders, supported by international partners, must adopt an integrated approach to secure the blue economy, foster peace, and promote sustainable development across the WIO.

Brigadier General John Waweru (Ret.) is a seasoned security strategist, educator, and conservation advocate with over three decades of distinguished service. He is currently a Fellow at the African Leadership University (ALU) and serves as Adjunct Faculty at the ALU School of Business, where he develops and teaches curriculum on security, leadership, and governance. A retired officer of the Kenya Defence Forces, General Waweru previously served as the Director General of the Kenya Wildlife Service, where he led national conservation efforts and advanced cross-sector partnerships for environmental security. Waweru holds a Master of Management in Security and is due to graduate in 2025 with a PhD in International Studies, reflecting his deep academic engagement with global security and governance issues. His areas of expertise include strategic leadership, crisis management, maritime security, and organizational transformation. He is widely respected for his contributions to regional security dialogue and for integrating conservation into national security frameworks. Waweru continues to mentor emerging leaders and contribute to thought leadership across Africa’s security and governance landscape.

Endnotes

1. Christian Bueger, “Who Secures the Western Indian Ocean? The Need for Strategic Dialogue” (Center for Maritime Strategy, September 19, 2024), https://centerformaritimestrategy.org/publications/who-secures-the-western-indians-ocean-the-need-for-strategic-dialogue/

2. Christian Bueger and Timothy Edmunds, “Blue Crime: Conceptualizing Transnational Organized Crime at Sea,” Maritime Policy 119 (2020), 104067; Laura C. Burroughs and Robert Mazurek, “Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean: Perceived Threats, Impacts, and Solutions,” (One Earth Future Foundation, June 14, 2019), https://oneearthfuture.org/en/secure-fisheries/publication/maritime-security-indian-ocean-perceived-threats-impacts-and-solutions

3. Francois Vrëy and Mark Blaine, “Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Attacks Expose Africa’s Maritime Vulnerability,” (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 9, 2024), https://africacenter.org/spotlight/red-sea-indian-ocean-attacks-africa-maritime-vulnerability/

4. WWF, “US $142.8 Million Potentially Lost Each Year to Illicit Fishing in the South West Indian Ocean,” May 4, 2023, https://www.wwf.eu/?10270441%2FUS1428-million-potentially-lost-each-year-to-illicit-fishing-in-the-South-West-Indian-Ocean; Oceans 5, “Ending destructive industrial fishing in Madagascar and the Western Indian Ocean,” (Oceans 5, n.d.), https://www.oceans5.org/project/ending-destructive-industrial-fishing-in-madagascar-and-the-western-indian-ocean/

5. Margherita Camurri, “Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean: The Practice of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing (Mondo Internazionale, February 10, 2022), https://mondointernazionale.org/focus-allegati/maritime-security-in-the-indian-ocean-the-practice-of-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-iuu-fishing

6. Blue Ventures, “A Shared Vision to Tackle Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing in the Western Indian Ocean,” June 16, 2023, https://blueventures.org/a-shared-vision-to-tackle-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-in-the-western-indian-ocean/

7. Bueger and Edmunds, “Blue Crime.”

8. “Piracy off the coast of Somalia,” Wikipedia Foundation, accessed April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piracy_off_the_coast_of_Somalia

9. Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo “Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea,” Africa Security Brief No. 30 (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 28, 2015); J.W. Mwangi, Maritime Terrorism in Kenya: Threats and Responses. (Nairobi: KeMU Press, 2021).

10. G. Macfadyen and G. Hosch, The IUU Fishing Risk Index: 2023 Update (Poseidon Aquatic Resource Management Limited and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2023), https://iuufishingindex.net/downloads/IUU-Report-2023.pdf.

11. Abhishek Mishra, “Maritime Security Architecture and Western Indian Ocean: India’s Stakes,” IDSA Comments, January 18, 2024 (Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses), https://www.idsa.in/publisher/comments/maritime-security-architecture-and-western-indian-ocean-indias-stakes/.

12. U.S. Embassy Antananarivo, “United States Partners with Western Indian Ocean Countries to Tackle IUU Fishing (U.S. Embassy in Madagascar, June 5, 2023), https://mg.usembassy.gov/united-states-partners-with-indian-ocean-countries-to-tackle-iuu-fishing/

13. Djibouti Code of Conduct, “Combating Maritime Security Threats in Western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden (n.d.), https://dcoc.org/combating-maritime-security-threats-in-western-indian-ocean-and-gulf-of-aden/; International Maritime Organization, “Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden States Push Coordinated Action on Maritime Security,” December 4, 2024,

https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/Pages/WhatsNew-2193.aspx

14. Bueger, “Who Secures the Western Indian Ocean.”

References

Blue Ventures, “A Shared Vision to Tackle Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing in the Western Indian Ocean,” June 16, 2023. https://blueventures.org/a-shared-vision-to-tackle-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-in-the-western-indian-ocean/

Bueger, Christian, “Who Secures the Western Indian Ocean? The Need for Strategic Dialogue. Center for Maritime Strategy,” September 19, 2024. https://centerformaritimestrategy.org/publications/who-secures-the-western-indian-ocean-the-need-for-strategic-dialogue/

Bueger, Christian and Timothy Edmunds, “Blue Crime: Conceptualizing Transnational Organized Crime at Sea,” Marine Policy 119 (2020), 104067.

Burroughs, Laura C. and Robert Mazurek, “Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean: Perceived Threats, Impacts, and Solutions,” One Earth Future, June 24, 2019. https://oneearthfuture.org/en/secure-fisheries/publication/maritime-security-indian-ocean-perceived-threats-impacts-and-solutions

Camurri, Margherita, “Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean: The Practice of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing.” Mondo Internazionale, February 10, 2022. https://mondointernazionale.org/focus-allegati/maritime-security-in-the-indian-ocean-the-practice-of-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-iuu-fishing

Djibouti Code of Conduct, “Combating Maritime Security Threats in Western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden,” (n.d.). https://dcoc.org/combating-maritime-security-threats-in-western-indian-ocean-and-gulf-of-aden/

International Maritime Organization, “Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden States Push Coordinated Action on Maritime Security,” December 4, 2024. https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/Pages/WhatsNew-2193.aspx

International Maritime Organization. Djibouti Code of Conduct. London: IMO, 2009.

Macfadyen, G. and G. Hosch, “The IUU Fishing Risk Index: 2023 Update.” Poseidon Aquatic Resource Management Limited and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2023. https://iuufishingindex.net/downloads/IUU-Report-2023.pdf

Mishra, Abhishek, “Maritime Security Architecture and Western Indian Ocean: India’s Stakes,” IDSA Comments, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. January 18, 2024. https://www.idsa.in/publisher/comments/maritime-security-architecture-and-western-indian-ocean-indias-stakes/

Mwangi, J. W. Maritime Terrorism in Kenya: Threats and Responses. Nairobi: KeMU Press, 2021.

Oceans 5, “Ending Destructive Industrial Fishing in Madagascar and the Western Indian Ocean,” Oceans 5, n.d. https://www.oceans5.org/project/ending-destructive-industrial-fishing-in-madagascar-and-the-western-indian-ocean/

Osinowo, Adeniyi Adejimi, “Combating Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea,” Africa Security Brief no. 30 Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 28, 2015.

“Piracy off the coast of Somalia,” Wikipedia Foundation, accessed April 21, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piracy_off_the_coast_of_Somalia

U.S. Embassy Antananarivo, “United States Partners with Western Indian Ocean Countries to Tackle IUU Fishing. U.S. Embassy in Madagascar, June 5, 2023. https://mg.usembassy.gov/united-states-partners-with-indian-ocean-countries-to-tackle-iuu-fishing/

Vogel, Augustus. “Investing in Science and Technology to Meet Africa’s Maritime Security Challenges.” Africa Security Brief, No. 10. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2011. https://africacenter.org/publication/investing-in-science-and-technology-to-meet-africas-maritime-security-challenges/

Vrëy, Francois and Mark Blaine, “Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Attacks Expose Africa’s Maritime Vulnerability.” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 9, 2024. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/red-sea-indian-ocean-attacks-africa-maritime-vulnerability/

WWF, “U.S. $142.8 million Potentially Lost Each Year to Illicit Fishing in the South-West Indian Ocean,” May 4, 2023. https://www.wwf.eu/?10270441/US1428-million-potentially-lost-each-year-to-illicit-fishing-in-the-South-West-Indian-Ocean

Featured Image: Suspected pirates surrender to a multinational naval force in 2009. (Photo via Reuters/Jason R. Zalasky/U.S. Navy)