By Ryan Hilger

Excerpted from the forthcoming Unexpected Victory: The U.S. Navy in the Sino-American War, 2034-2036 by Fred Goures, to be published by Random House in December 2039.

…Several Chinese admirals agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity on the following question, among others: “What surprised you most about the war?” Their answers were remarkably similar: the Yukon-class corvettes. Named after American rivers, the Navy built and deployed more than 60 Yukons in three years from 2033-2036. One Chinese admiral’s remarks are typical:

Admiral [redacted]: The Yukons caught me and the PLA leadership completely by surprise. When we started the war in October 2034, we thought we would have the American Navy sunk in a few weeks. We knew the submarine threat would take time, but we did not consider their surface forces much of a threat.

Goures: Why was that?

Admiral [redacted]: It was clear from decades of industrial espionage and intelligence collection that the American Navy had not managed to introduce much in the way of new technologies in decades, despite the focus on innovation. Thus, the introduction of the Yukons did not draw much attention from us.

Goures: Why not?

Admiral [redacted]: They were much smaller and seemed simpler than the American mainstay, the Arleigh Burke-class. We did not see how they could have posed much of a threat to us. We were very wrong on this.

Goures: How so? What made the Yukons different?

Admiral [redacted]: In retrospect, their simplicity was pure elegance. The Americans seemed to be able to upgrade and repair them so rapidly, even while at sea. We never seemed to fight the same ship twice. It may have been the same hull, but each encounter demonstrated new capabilities that we did not anticipate, usually without the ship ever pulling into a port. We could not keep up…

______________________________________

Admiral Peter Malone, the Program Executive Officer (PEO) for Ships in 2031, recalled sitting in a meeting with senior Navy leadership when the idea of what would become the Yukon class was born:

Things were not going well at all. The Large Surface Combatant program had not panned out in the 2020s like we thought. Apparently, we did not learn the lessons of the Zumwalt or Littoral Combat Ship programs sufficiently, because we repeated many of the same mistakes. After the fourth year of Congressional cuts to the program and reductions in planned numbers of hulls, the Secretary of the Navy called for a meeting to discuss options.

I had only been in the PEO Ships job for a few months, but I did not see how we could recover. My mind drifted from the conversation to the problems the Navy overcame to deliver both a ballistic missile submarine and a submarine-launched ballistic missile in less than five years in the 1950s – and with an immense amount of new technology to boot. I wondered how we had managed to drift so far from such incredible origins.

I snapped back from my daydream and saw the Chief of Naval Operations glaring at me. “Do you have any ideas, Pete?” I nodded and thought for a moment, but I already knew what I needed to say.

“Kill the program.” There were a lot of shocked expressions.

“Clearly what we have done in the past has not been working. Let’s throw out the playbook and try something completely new. I’ve got some ideas on ship construction, digital engineering, and how to develop products differently. Give me six months and I will come back to you with a proposal for a new ship class and how we will deliver them to the fleet.”

After a few moments of incredulous silence, he looked at Admiral Higgs, the Commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet, “Dan, what do you think?”

“Well, I don’t see anything to lose from this. Most of my requested capabilities were dropped in last year’s budget cuts anyway. This at least may get me more ships sooner, which is really what I need to balance against China.”

The CNO let the tension hang in the air before replying. “We have everything to lose if we fail this time. Let’s get it right.” Off we went.

_______________________________________

The Yukon-class had a very interesting beginning. It was the first government-designed and built ship in decades. Many questioned the government’s sanity in taking on the challenge of designing a ship after contractors had done it for so many years, but the government was left with little choice. Captain Lucius Walker, the Program Manager of the LSC program, recalls the day their hand was forced. On May 25, 2031, Captain Walker and his team held an Industry Day to discuss the radical new ideas they had.

We thought we had a really awesome set of ideas for industry. My team had spent a lot of time doing futuring exercises, talking with operators, looking at the case studies of Fitzgerald and John McCain from a damage control perspective, reviewing the failures of the Littoral Combat Ship program, and culling the new technologies to see what could meet the mission needs in the threat environment of the 2030s and beyond. The environment was very missile-centric, which amounted to a huge departure from traditional gun damage-tolerant designs. Those had not changed much since World War II.

The shock came right away. Both Lockheed Martin and General Dynamics said that we could not do what our Industry Day proposal requested. Too much of it relied on proprietary information and lead integrator efforts and products. We had a heated discussion in the Gooding Center on the [Washington Navy] Yard, but they weren’t going to budge. I could understand their position. They had spent decades cultivating an integrated set of systems; you simply could not break them apart the way we were talking about. It was then that I knew we had to bring the design in-house.

_______________________________________

After the collapse of the Industry Day in May 2031, Captain Walker’s Ship Design Manager, Austin Corleone, spoke with Captain Walker outside the Gooding Center:

I decided to go for it. “Do you have a few minutes, Captain?”

“Sure, why not? I don’t really want to go back in there at the moment.”

“Ever since we finalized the Industry Day proposal, I’ve been thinking about different ways to bring the ideas into a ship.”

“Shoot.”

“I think we can design a simple ship in-house.”

“Come again?”

“Bear with me. It doesn’t have to be complex. We can design the hull and space allocations for all the major systems: radars, combat systems, weapons, etc. We work with other program offices to deliver those subsystems to the strict interfaces that we provide. Remember in 2002 when Amazon forced their internal programs to communicate only through certain interfaces or be fired? We don’t need to design the entire ship, just require programs to provide models to fit into the spaces and interfaces we give them. We make the mechanical and electrical systems very simple and easy to replace—no more rats’ nests of cables everywhere. In that way, we can use the digital models to see how all the parts fit together into a coherent whole. Software standards in industry have moved to the extreme in terms of modularity with service mesh architectures, and I see no reason why we can’t do the same with ship designs.”

“You’re serious, aren’t you?”

“Absolutely. I’ve got a few friends who think along the same lines in other program offices that think it would be feasible. What do you think?”

“Can you get your friends together at our office tomorrow to map out what this might look like? I’m curious.”

“I’ll get it set up.”

The Yukon program office exploited the fast, inexpensive, restrained, and elegant criteria to the letter in designing the ships. The use of model-based engineering techniques stemming from the Digital Engineering Strategy combined with a confederation of program offices allowed the Yukon program to design a ship in record time. They approached allowed individual program offices to be the experts in their area, freeing the Yukon team to design an overmatch of hull, mechanical, and electrical services for the programs to use. The result was a simple, elegant ship that was easy to build, upgrade, repair, and operate.

_______________________________________

The Yukon program embraced its new role as a lead systems integrator. Once the hull design and its associated services had been finalized, they contracted to start hull construction, without any of the major subsystems ready. Captain Walker made the key decision to revert to a historical norm: outfitting at the pier. The Navy had gotten away from it as ship designs increased in complexity, but it briefly resurfaced with the Zumwalt-class, though more by accident than planning. Designing the ship for ease of access allowed the pier-side outfitting to be conducted rapidly by both sailors and contractor teams. Ships were commissioned at an unheard of rate with the latest gear that the confederation of program offices could deliver.

As the ships deployed, the various program offices continued to support the ships by providing for over-the-air delivery of software to give the ships the maximum capability possible against the adversaries. The independence of hardware and software allowed designers to consider sensors in fundamentally new ways, and the surface fleet saw radically new capabilities from the same hardware as a result. The independent, digitally-engineered design allowed for rapid upgrades to the ships while deployed, in some cases with new hardware even being delivered via small drones in the South China Sea. The seamless integration that digital engineering and DevSecOps created allowed the programs supporting Yukons to achieve update and repair speeds that were orders of magnitude faster than the Navy had ever thought possible. As a result of these design decisions, the ships performed remarkably well in combat, earning rave reviews from the sailors operating them to the adversaries fighting against them.

Lieutenant Commander Ryan Hilger is a Navy Engineering Duty Officer stationed in Washington D.C. He has served onboard USS Maine (SSBN 741), as Chief Engineer of USS Springfield (SSN 761), and ashore at the CNO Strategic Studies Group XXXIII and OPNAV N97. He holds a Masters Degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Naval Postgraduate School. His views are his own and do not represent the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the Department of the Navy.

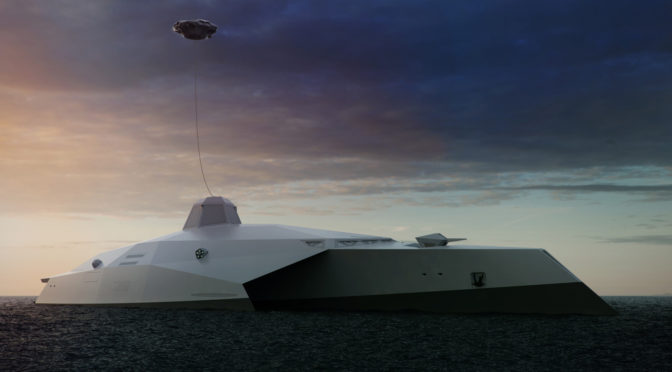

Featured Image: “Dreadnought 2050” by Rob McPherson (via Artstation)