By Clay Robinson

It was a sunny morning with calm seas on March 6, 2024, a fine day for sailing the tranquil waters of the Gulf of Aden. The crew of M/V True Confidence, however, were on edge: less than 10 hours before, their ship had come under attack from a Houthi-launched Iranian missile. Through sheer luck, the missile missed its intended target, and the ship continued its westerly journey bound for Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. At 11:34 AM, the crew’s luck ran out: another Houthi missile ripped through the deck house, exploding in a massive fire ball that set the bridge ablaze.1 Two innocent civilian mariners were killed and four more critically injured. The captain ordered the fifteen surviving crew to abandon ship, leaving it adrift and in flames, yet another victim of the Houthis’ senseless and indiscriminate violence.

Red Sea Fast Pass: Chinese Opportunism

Even as the tumultuous situation in the Red Sea takes ever more deadly and dangerous turns, China continues to sit idly by and reap the economic and diplomatic benefits thanks to the Houthis’ Iranian patronage and their own calculated self-interest. While much of the world’s shipping has been forced to take longer and more expensive routes to avoid Houthi missiles in the Red Sea, Chinese shipping continued virtually undisturbed, protected as it were under a modern day “non-aggression pact” between China and Houthi forces.2 However, just a few days after the Houthis granted this assurance to China that their ships would not be targeted in exchange for political support, on March 23, 2024, a Houthi missile struck the Chinese-owned M/V Huang Pu.3 Houthi spokesmen were unusually tight-lipped4 after this attack, likely the result of severe chastisement behind the scenes by both China and Iran, and will take extra efforts to avoid targeting Chinese shipping in the future.

It is not clear yet whether this Houthi attack should be attributed to an administrative oversight, missing that M/V Huang Pu’s ownership had recently transferred to China. Or perhaps the Houthis were targeting another vessel nearby. Either way, the safest place to transit the Red Sea is now onboard Chinese-owned ships.

The combination of the Houthi’s public agreement with China to not target their shipping and the likely private reprimand after striking the M/V Huang Pu sets up a scenario whereby Chinese shipping will be getting a free pass through the Red Sea. That provides China a significant competitive advantage at the precise moment its economy is starting to falter. There is a way, however, to both remove that advantage and force China to abide by its international obligations.

The time has come to exact a cost on this unbridled Chinese opportunism.

Panda Express: A Proposed Convoy Operation

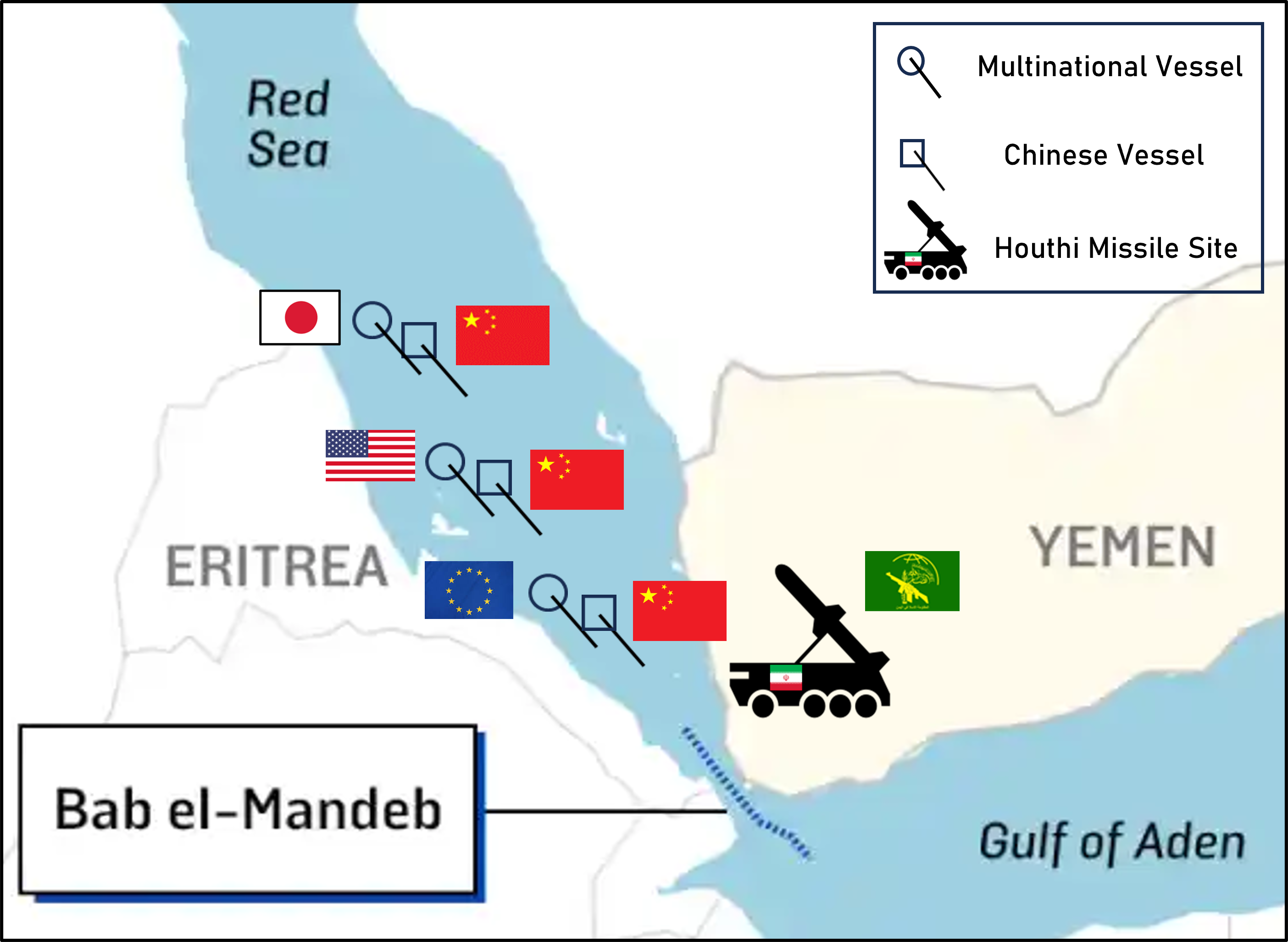

The idea is simple: vulnerable multinational commercial vessels would closely shadow Chinese ships as they transit safely past Houthi missile launchers in a convoy-type operation. The Houthis, knowing their targeting is lacking, would refrain from shooting lest they accidentally hit a Chinese ship and anger both Beijing and Tehran. The U.S.-led Combined Maritime Forces or the European Union Naval Forces’ Operation Aspides are the most obvious candidates to organize such a convoy – nicknamed Panda Express – but arguably it could be self-organizing or organized under an alternative multinational coalition. The shipping industry could institute a loosely organized program to surreptitiously appropriate passive escort of commercial vessels by Chinese vessels sharing the same shipping lanes. In short, these vessels will shadow Chinese vessels at a safe but proximate distance such as to keep the Chinese vessel between them and the direction of the Houthi missile threat. A limited handful of multinational commercial vessels will transit under the shield of the security that each of the Chinese vessels enjoy, taking advantage of a reliable and predictable, yet passive escort courtesy of China.

The current situation (Figure 1) consists of multinational commercial vessels transiting independently under the impressive but less-than-omnipresent protection of the multinational warships participating in Operation Prosperity Guardian and Operation Aspides. These warships endeavor to intercept Houthi missiles and attack drones targeting commercial shipping.

A brief vignette will serve as an example of what Panda Express might accomplish. Prior to a southbound transit of the Red Sea, a multinational commercial vessel will loiter temporarily at the southern end of the Suez Canal, awaiting the passage of another southbound Chinese vessel. This will occur ostensibly every few hours as an average of over five Chinese vessels transit the Suez Canal per day.5 The multinational vessel will then take station on the starboard quarter of the Chinese vessel at a safe distance, but in close proximity such that a sort of passive, perhaps even unwitting, screen of the vessel by the Chinese vessel will occur (Figure 2).

Some might argue that Panda Express would put innocent civilian mariners at risk by shadowing Chinese merchant vessels, and from a practical standpoint, that threat would exist. But therein lies its value as a deterrent because the Houthis have already stated that they will not attack Chinese shipping. As the two vessels reach the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, air defense vessels of Operation Prosperity Guardian and Operation Aspides can provide a more robust ability to detect and engage any Houthi missile that might be close enough to discern the multinational vessels from the Chinese one. Once through the western reaches of the Gulf of Aden and outside the threat area, the vessel can once again resume navigating independently.

Panda Express leverages opportunities fomented by China for both a protective and influence advantage. This concept is not an evaluation of the technical aspects of a possible tactical advantage on a notional battlefield. Assessments would need to be made about just how close these vessels would have to transit near their Chinese escorts to achieve sufficiently low levels of probability hit (PH) or probability of kill (PK) for inbound Houthi missiles. Similarly, there would be limits to how many vessels could safely transit in company with each Chinese vessel. This concept is rather about taking advantage of the deterrent value of the present situation and using it as a way to exact diplomatic costs on China for sticking to its opportunistic agenda in the Middle East. This is a way to erode China’s economic and diplomatic advantages by highlighting China’s malign opportunism and providing safe passage through the Red Sea. Panda Express is a low cost, legal, and pragmatic way to compete with China.

What will Panda Express accomplish? This escort tactic would begin to serve as a strategic deterrent against Houthi attacks in three ways. First and foremost, the risk of the Houthis accidentally hitting a Chinese vessel while targeting other vessels one would be too great, and it would deter attacks on any ships traveling in close company with Chinese ships. Additionally, Panda Express could reduce the strain on the contingent of warships supporting Operation Prosperity Guardian and Operation Aspides that are spread very thin by helping to better position these assets in order to more efficiently focus their layered defense on the places where they can be most effective. Lastly, diplomatically, China could be held accountable for malign hedging behavior and an opportunistic silent partnership with Iran. Panda Express could drive China to increase pressure on Iran to rein in all Houthi attacks, not just prevent attacks on Chinese vessels.

How long could Panda Express be sustained? There are risks to be sure, but most are worth accepting. China might stop sending its ships through the Red Sea, but this is extremely unlikely. The Suez Canal and Red Sea serve as the primary route for China’s westward shipments of goods, including around 60% of its exports to Europe, representing one-tenth of the Suez Canal’s annual traffic.6 China cannot afford to avoid the Red Sea route altogether.

The maritime shipping industry can determine that the cost of loitering at the entrances to the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to wait for Chinese escort are too high. Yes, loitering temporarily for a few hours costs some money, but it is also likely to be far less than transiting around the Capes of Africa.

All this cat and mouse activity on the high seas might lead to collisions between vessels, but these are professional mariners with years of experience plying these waters. They can handle it. And, if Chinese ships were to be instructed to somehow attempt to disrupt this passive escort program, it will only cost them more in time and money.

China: A Silent Partner in the Axis of Insecurity

Is Panda Express worth it? Some points to consider: Chinese leaders have repeatedly claimed they hold very little sway over Iran, and by extension the Houthis; however, several key factors seem to indicate otherwise, and China’s opportunistic fingerprints are all over the Red Sea crisis. China asked Iran to rein in the Houthis.7 China is not alone in asking Houthis to cease the attacks.8 Yet, the Houthis publicly stated only Chinese and Russian ships have a free pass.9

China knows its ships are safe, too. Despite having a significant naval presence in the region, China has kept its Naval Escort Task Force (NETF) out of the Red Sea, choosing instead to loiter in the safer waters of the eastern Gulf of Aden. In late February, the Chinese Defense Ministry denied the 46th NETF deployment is related to the Red Sea crisis and reiterated that it is a “regular escort operation.”10 That none of these NETF vessels are needed in the Red Sea to ensure the safe passage of Chinese shipping is proof China knows its vessels are exempt from Houthi attack.

China does indeed have influence over Iran and, by extension, the Houthis in what has now become an “Axis of Insecurity.” Panda Express would reduce the likelihood of new attacks like that on M/V True Confidence and M/V Huang Pu and put direct pressure on China to either explain to the court of international opinion why shadowing Chinese vessels is a safe tactic, or influence Iran and the Houthis to end their aggression in the Red Sea altogether. Either way, China loses, and the rest of the world wins. It’s time to order Panda Express.

Commander Clay Robinson is a retired surface warfare officer and antiterrorism/force protection specialist. He has worked for the U.S. Department of Defense since 2017 as a strategic planning specialist and is currently an Adjunct History Instructor with the U.S. Naval Community College. He served on board the USS Russell (DDG-59), USS Laboon (DDG-58), and USS Nitze (DDG-94), and commanded Maritime Civil Affairs Squadron One (MCAS-1).

Endnotes

1. Jonathan Saul, “Ship evacuated after first civilian fatalities in Houthis’ Red Sea attacks,” Reuters, March 7, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/ship-evacuated-after-first-civilian-fatalities-houthis-red-sea-attacks-2024-03-07/.

2. Sam Dagher and Mohammed Hatem, “Yemen’s Houthis Tell China, Russia Their Ships Won’t Be Targeted,” Bloomberg, March 21, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-21/china-russia-reach-agreement-with-yemen-s-houthis-on-red-sea-ships

3. Luther Ray Abel, “Chinese Tanker Struck by Houthi Missile,” National Review, March 24, 2024, https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/chinese-tanker-struck-by-houthi-missile/

4. Heather Mongilio, “Chinese Tanker Hit with Houthi Missile in the Red Sea,” USNI New, March 24, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/03/24/chinese-tanker-hit-with-houthi-missile-in-the-red-sea

5. “Suez Canal Blocking Could Hike Freight Fees between China and Europe If Not Cleared Soon: Analyst,” Global Times, March 24, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219372.shtml.

6. Amr Salah Mohamed, “China’s growing maritime presence in Egypt’s ports and the Suez Canal,” Middle East Institute, November 3, 2023, https://www.mei.edu/publications/chinas-growing-maritime-presence-egypts-ports-and-suez-canal.

7. Parisa Hafezi and Andrew Hayley, “Exclusive: China presses Iran to rein in Houthi attacks in Red Sea, sources say,” Reuters, January 25, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/china-presses-iran-rein-houthi-attacks-red-sea-sources-say-2024-01-26/.

8. Burak Bir, “24 countries condemn Houthi attacks in Red Sea,” Anadolu Agency (AA), January 24, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/24-countries-condemn-houthi-attacks-in-red-sea/3117236.

9. “China and Russia Get a Free Pass Through Houthis’ Red Sea Blockade,” The Maritime Executive, January 23, 2024,

https://maritime-executive.com/article/china-and-russia-get-a-free-pass-through-houthis-red-sea-blockade.

10. Zhao Ziwen, “Why China’s Red Sea diplomatic mission is unlikely to stop Houthi shipping attacks,” South China Morning Post, March 4, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3253641/why-chinas-red-sea-diplomatic-mission-unlikely-stop-houthi-shipping-attacks.

Featured Image: Photo of the MV True Confidence after it was struck by a Houthi anti-ship ballistic missile in the western Gulf of Aden, March 6, 2024. (Photo courtesy U.S. Central Command)