By Christopher Nelson

Recently, Captain Michael Junge published an interesting book on why and under what circumstances the U.S. Navy relieves commanding officers. His book, Crimes of Command, begins in 1945 and proceeds through numerous historical case studies up to the modern era. I think many people – not only those in the surface warfare community – but commanders, leaders, and sailors in other communities will find our exchange interesting.

The book is worth your time – and it is a perennial topic that deserves attention.

Nelson: Would you briefly describe what the book is about and why you wanted to write it?

Junge: In short, it’s about why the Navy removes commanding officers from command – the incidents that lead to removal, the individuals removed, and what the Navy does about the incident and the individual. But instead of a look at just one or two contemporary cases, I went back to 1945 and looked across seven decades to see what was the same and what changed.

Nelson: In the book, when referring to the process of relieving commanding officers, you talk about words like “accountability,” “culpability,” and “responsibility.” These words, you say, matter when talking about why commanding officers are relieved. Why do they matter and how do they differ?

Junge: The common usage blends all three into one – accountability. We see this with the press reports on last summer’s collisions – the Navy’s actions are referred to as “accountability actions.” Most people, I think, read that line as “punitive actions” mostly because that’s what they are. But accountability isn’t about punishment – it’s about being accountable, which is to give an accounting of what happened, to explain one’s actions and thoughts and decisions. The investigations themselves are an accountability action. The investigations are supposed to determine who was responsible for the problem, what happened, who was at fault, and then determine if within that responsibility and fault there is also culpability.

Culpability is about blame – accountability is not, even if we use it as such. In investigations, when you mix culpability, blame, and accountability together end up being about finding fault and levying punishment instead of finding out what happened. That keeps us from learning from the incident and preventing future occurrences. We’ve completely lost that last part over the past few decades if we even had it to begin with. Every collision I looked at, for example, had four or five things that were the same – over seven decades.

Nelson: Later in the book, you say that as virtues, honor, courage, and commitment are not enough. How should we reexamine those virtues? Isn’t this always the challenge – the challenge of the pithy motto vs. the substantive truth, that’s what I was getting at. And it’s not that there is some truth to the motto or slogan, but rarely are they sufficient alone – yes?

Junge: Honor, courage, and commitment make for a great slogan, but will only be inculcated in the force when our leaders routinely say them and live by them. I wrote a piece for USNI Proceedings in 2013 that commented on how naval leaders rarely used those words. That hasn’t changed. If they are used it’s in prepared text and often used as a cudgel. Leaders need to exemplify virtues – we learn from their example – and if they don’t use the words we don’t really know if they believe in them. But they are a great start, and they are ours – both Navy and Marine Corps.

What I meant in the book is that honor, courage, and commitment aren’t enough for an exploration of virtues in general. For the Navy, they are an acceptable starting point. For individual officers, or for the Naval profession, we need to think deeper and far more introspectively. My latest project is looking at the naval profession and a professional ethic. My personal belief is that we don’t need, or want, an ethical code. Or if we have one it needs to be like the Pirate Code – more as guidelines than rules. There’s science behind this which is beyond our scope here, but rules make for bad virtues and worse ethics. Rules tend to remove thought and press for compliance. At one level that’s great, but compliance tends to weed out initiative and combat leaders need initiative.

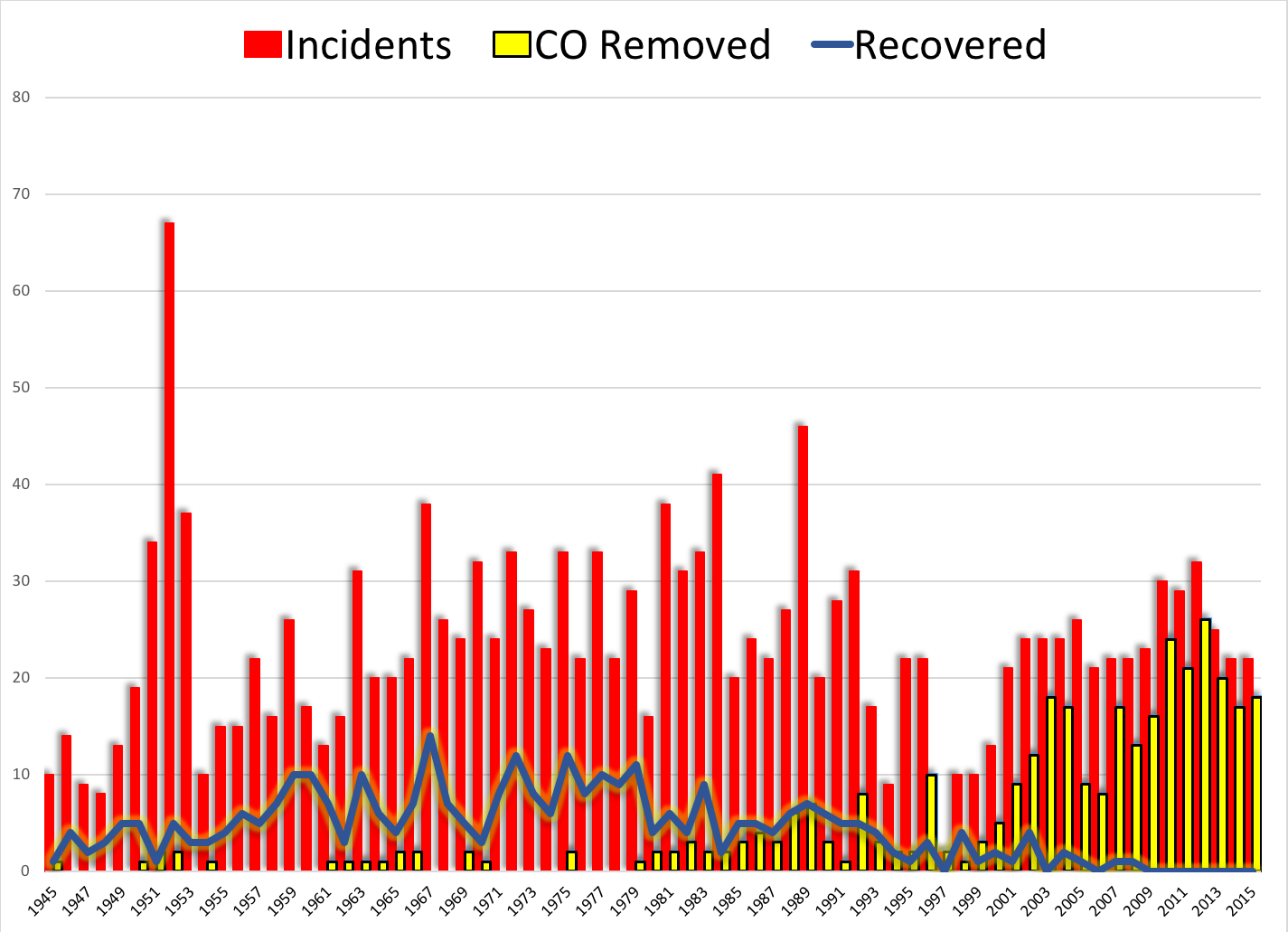

Nelson: So, after studying the historical data and specific events from 1945 to 2015, what did you conclude? Why are there more commanding officers relieved today than there were fifty years ago?

Junge: Even after all the research and the writing, this is a tough one for me to encapsulate. In my dissertation defense, I made a joke at the end that the reason we remove more officers now is complicated. And it is. Every removal is a little different from the others. That makes linking details difficult. But, when you lift back a little and take a really long view, I could find some trends. Not only do we remove more commanders today, we do it for more reasons, and we have almost completely ended any sort of recovery for officers removed from command.

Without giving too much away, because I do want people to read the actual book, today’s removals come down to a couple of things – press, damage (material or emotional) to the Navy, and the commander’s chain of command. If the chain of command relationship is poor, the press gets a story, and there is some level of damage to the Navy (metal bent, people hurt, or image tarnished) then the commander is likely to go. But it’s not a direct line. Sometimes the information comes out later – we saw this with USS Shiloh last year and in one of the cases I covered, the helicopter crash in USS William P Lawrence. Neither commander was removed from command, but both careers were halted after the investigations were done and the administrative side of the Navy took over. If those incidents happened in the 1950s or 1960s, both commanding officers would have unquestionably moved forward with their careers. Whether that would be good or bad depends entirely on what those officers might have done with the knowledge gained from the investigations that challenged their leadership and individual character but we won’t know anymore. Maybe we should.

Nelson: When you started this book and after looking at the data, did anything surprise you? Did you go in with particular opinions or develop a theory that the data disproved or clarified?

Junge: When I started this I was pretty sure there were differences. One of the reasons I pulled all the data together was because in 2004 the Navy Inspector General issued a report that said, in essence, that a one percent removal rate was normal. If one percent was normal in 2004, when we had fewer than 300 ships, then we should have heard something about removing COs when we had 1000, or 3000, ships. But, we didn’t. So that there was a change wasn’t surprising.

I started off thinking that Tailhook was a major inflection point. I intended a whole chapter on the incident and investigation. In the end, the data didn’t support it – the inflection had already happened and Tailhook, especially its aftermath, was indicative of the change. I’m not minimizing the impact Tailhook had on Navy culture – we are still dealing with echoes twenty-five years later – but for the trend of removing commanders, it wasn’t a watershed. Likewise, I thought the late 1960s to early 1970s might be an inflection point – we had a rough couple years with major collisions, attacks, fires, Vietnam – but the data showed it wasn’t the turning point I expected.

It wasn’t until I plotted the information out that I saw the inflection of the early 1980s. When I saw the changes in the graph I had to go back to the research to sort out why. It was both frustrating and encouraging. It showed me I wasn’t trying to force data to fit a pre-selected answer, but it also meant leaving a lot of research behind.

Nelson: You go into some detail in your book about court-martials. Historically, why does the navy rarely take commanding officers to court martial?

Junge: The simple reason is that the Navy has a difficult time proving criminal acts by commanding officers. It’s not a new problem. When officers are taught to think for themselves and have sets and reps thinking critically, then when on a jury they are likely to take the evidence and make their own minds up. And that conclusion may run counter to what Navy leadership wants. Getting courts-martial into that real true arbiter of guilt and innocence was a major win for the post-World War II military. But, since leaders can’t control courts-martial anymore we now see this major abuse of administrative investigations, which runs counter to our own regulations on how we are supposed to handle investigations of major incidents and accidents.

Nelson: In fact, you threw in an anecdote in your book about Nimitz issuing letters of reprimand to the jury members on Eliot Loughlin’s court-martial. This was fascinating. What happened in that case?

Junge: In April 1945, Lieutenant Commander Charles Elliot Loughlin sank a ship without visually identifying it. The ship turned out to be a protected aid transport with 2,000 civilians aboard. Nimitz removed Loughlin from command and ordered his court-martial. The court found Loughlin guilty but only sentenced him to Secretarial Letter of Admonition. Nimitz was reportedly furious and issued letters of reprimand to the members of the court. In just answering this question I realize I never dug deep into what happened to those members – I might need to do that.

Anyway, that was a rare case of Nimitz being angry. And in retrospect, I wonder if he was angry, or if he was protecting the court from the CNO Admiral King. There’s a story I’ve been percolating on in how Nimitz and King had differing ideas of responsibility and culpability. King was a hardliner – King could be seen as the archetype for modern culpability and punishment. There were some exceptions but he was pretty binary – screw up, get relieved. Nimitz was the opposite. Halsey put Nimitz into multiple tough spots where Halsey probably should have been removed from command – but Nimitz knew Halsey and erred on the side of that knowledge rather than get caught up in an arbitrary standard. That’s why I think those letters were out of character. But I have to temper that with the very real knowledge that Loughlin committed a war crime, was pretty blasé about it, blamed others, very likely put American prisoners of war in more danger than they already were, and might have endangered the war termination effort. Those conclusions run counter to the modern mythology around Loughlin, but are in keeping with the actual historical record.

Nelson: And if I recall, there was an XO that chose court martial rather than NJP ten or so years ago after a sailor on the ship was killed during a small boat operation. The XO was exonerated and cleared from any wrongdoing by the jury. Fleet Forces ended up putting a statement out how he disagreed with the verdict.

Junge: USS San Antonio – LCDR Sean Kearns. Sean remains one of my heroes for forcing the system to do what it says it will do. I firmly believe that Admiral Harvey stepped well outside his professional role and made his persecution of Sean a personal matter when he issued some messages and letters after the acquittal. I know among many SWOs that Harvey’s actions after the verdict really altered their opinions of him. Sean’s case is also major reason I am in favor of the Navy ending the “vessel exception” which precludes anyone assigned to a sea-going command from refusing non-judicial punishment and demanding a court-martial. Too many Navy leaders abuse this option. I know of a story where an officer was flown from his homeport to Newport, RI for non-judicial punishment, and another where an officer was flown from Guam to Norfolk for NJP. There are more cases where officers were removed from command, but kept assigned to sea duty so that they could not refuse NJP. That this even happens completely belies the intent behind the vessel exception.

Nelson: You also talk in some detail about Admiral Rickover and the culture he fostered and how that culture affected command. Overall, how did he affect command culture?

Junge: This was my biggest surprise. If you’d talked to me before I started and asked about Rickover I’d have easily said he had nothing to do with the changes. Wow –that was wrong. I’m not sure how I could ever think that someone who served almost 30 years as a flag officer, hand selected each and every nuclear-trained officer, and personally inspected each and every nuclear ship for decades didn’t influence Navy culture. Rickover ends up with the better part of a chapter in a story I didn’t think he was even part of. But, the culture we have today is, I think, not the one he intended. Maybe.

Rickover was, and remains, an individual who brings up conflicted memories and has a conflicted legacy. Like many controversial figures, the stories about him often eclipse the reality behind them. I’ll paraphrase a student who spoke of my colleague, Milan Vego, and his writings – you have to read about Rickover because if you just reject him completely, that’s wrong – and if you just accept him at face value, that’s wrong – you have to read and think and read some more, then come to your own conclusion. I can tell you that in the professional ethic piece I am working on, I expect Rickover’s legacy to play an important part.

Nelson: If I recall, I believe you self-published this book. How was that process? Would you recommend it for other writers? What did you learn when going through this process for publication?

Junge: The process, for me, was pretty simple. Getting to the process was very difficult. We know the adage of judging a book by its cover – well there’s also a stigma of judging a book by its publisher.

Actually getting a book published through an established publisher, the conventional process, takes well over a year and is full of norms and conventions that, from the outside, seem unusual. In the same way that we wonder “how did that movie get made?” when you go through the process of publishing, you start to wonder “how did that book get published?” I have a long time friend who is a two-time New York Times bestselling author who gave me some great advice on the conventional route. Just getting the basics can take up to an hour of discussion.

I tried the conventional route but after sending dozens of emails to book agents and getting only a few responses back, all negative, I checked with a shoremate who self-published his own fiction and decided to take that route partly out of impatience, frustration, and curiosity. I’m just good enough at all the skills you need to self-publish that it worked out to be pretty easy, with one exception – publicity. I’m not good at self-promotion so even asking friends to read the book and write reviews was a challenge.

Anyway, whether I recommend the self-publication process – it depends entirely on your own goals and desires. I wanted my book read – that was my core focus. To do that I could have just posted a PDF and moved on. But, I also wanted to make a few dollars in the process – and people who pay for a book are a little more likely to read it. This book grew out of my doctoral dissertation and I have a friend who is doing the same thing – but his goals were different. His core goals are different – he’s a full-on academic and needs the credibility of an academic publishing house for his curriculum vitae. We both defended around the same time – his book comes out sometime next year. I’m happy to spend more time talking about what I learned in the process, but the best advice I can give is for authors to figure out their objectives first. That is probably the most important thing. Everything else can fall into place after that.

Nelson: I ask this question in many of my interviews, particularly of naval officers – if you had ten minutes with the CNO, and if he hadn’t read your book, what would you tell him about Crimes of Command? What would you recommend he do to change the culture if change was necessary?

Junge: I really thought about punting on this one and running the note our Staff Judge Advocate has been running about Article 88 and Article 89 of the UCMJ (contemptuous words and disrespect toward senior commissioned officers). If I had ten minutes with CNO I doubt I would get 60 seconds of speaking time. My conclusions run completely counter to Navy lore about accountability and 10 minutes isn’t enough time to change anyone’s mind. But, as I thought about it I think I would say this: “CNO, we have really got to follow our own instructions. If an instruction says ‘do this’ then we need to do it, or change the instruction. We can’t have flag officers making personal decisions about this rule or that based on short-term ideas and feelings. If the situation doesn’t fit the rule, either follow the rule with pure intent or change the rule. But we can’t just ignore it. That’s an example that leads us, as a profession, down bad roads.” I would hope that question would then lead to a conversation of leadership by example that would include everything from Boards of Inquiry to travel claims to General Military Training.

Nelson: Sir, thanks for taking the time.

Michael Junge is an active duty Navy Captain with degrees from the United States Naval Academy, United States Naval War College, the George Washington University, and Salve Regina University. He served afloat in USS MOOSBRUGGER (DD 980), USS UNDERWOOD (FFG 36), USS WASP (LHD 1), USS THE SULLIVANS (DDG 68) and was the 14th Commanding Officer of USS WHIDBEY ISLAND (LSD 41). Ashore he served with Navy Recruiting; Assault Craft Unit FOUR; Deputy Commandant for Programs and Resources, Headquarters, Marine Corps; Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Communication Networks (N6); and with the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He has written extensively with articles appearing in the United States Naval Institute Proceedings magazine, US Naval War College’s Luce.nt, and online at Information Dissemination, War on the Rocks, Defense One, and CIMSEC. The comments and opinions here are his own.

Christopher Nelson is an intelligence officer in the United States Navy. He is a regular contributor to CIMSEC and is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, Rhode Island. The questions and views here are his own.

Featured Image: (FORT BELVOIR, Va. (May 04, 2017) Hundreds of service members at Fort Belvoir Community Hospital gathered before daybreak and celebrated their unique service cultures and bonds as one of the only two joint military medical facilities in the U.S. during a spring formation and uniform transition ceremony May 4, 2017. (Department of Defense photos by Reese Brown)

During interwar periods in different countries similar ships were called sloops, gunboats, or avisos. At the outbreak of WWII, the name corvette was revived by the British Royal Navy for a class designed to meet a pressing need for cheap and mass produced ASW escorts. As a result, a design based on a whale catcher became probably the most famous corvette type, the Flower class, the hero of Nicholas Monserrat’s novel Cruel Sea.

During interwar periods in different countries similar ships were called sloops, gunboats, or avisos. At the outbreak of WWII, the name corvette was revived by the British Royal Navy for a class designed to meet a pressing need for cheap and mass produced ASW escorts. As a result, a design based on a whale catcher became probably the most famous corvette type, the Flower class, the hero of Nicholas Monserrat’s novel Cruel Sea.