Andrew Cockburn. Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins. Henry Holt Publishers. 307pp. $28.00.

It’s not often that a book review coincides with current events. Books, particularly nonfiction, are usually written and published months, if not years after an event has occurred. That’s because good nonfiction is written in retrospect: writers have spent some time absorbing their subject, researching and analyzing the facts; authors are hesitant to be rash in judgment or thought.

However, there are exceptions. Some pieces of nonfiction, particularly journalists’ works, are appropriate now — not later. Andrew Cockburn’s new book, Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins, is one of them. Cockburn’s book is timely. In just the past few weeks there has been a flood of reporting from media outlets stating that a drone strike killed an American and an Italian hostage when targeting a group of Al-Qaeda members operating near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

Suddenly, questions about drone strikes, the debate about targeted killing, and the transparency of the drone program are on the front page of print and online news media worldwide.

Yes, timely indeed.

Although Cockburn’s book cover is plastered with silhouettes of unmanned aerial vehicles — with what appears to be the X-47B, Predator, Global Hawk, and Fire Scout, among others — he is making a larger argument. Cockburn it seems, is arguing that all technology is suspect. It’s not simply unmanned aerial vehicles, but it’s the idea that human beings are continuously so bold as to come up with technological solutions that will win our wars. History, however, tells us a much different story.

Cockburn, then, starts his book with an interesting tale.

In 1966 the Vietnam War was not going well. Secretary McNamara, a man who was fond of scientific solutions to difficult problems, turned his attention to “The Jasons.” The Jasons, Cockburn says, were a small group of scientists and scholars, many of whom would go on to become Nobel Prize winners. These were also some of the same men — Carl Kaysen, Richard Garwin, George Kistiakowski — that were part of the Manhattan Project some twenty years earlier.

The Jasons tried to do what Rolling Thunder could not — they tried to figure out a way to defeat North Vietnam’s ability to use the Ho Chi Minh trail — to cut off their supply routes. They ended up deploying small sensors along the trail that could, presumably, pick up the noise, vibration, and in some cases, the ammonia of someone urinating, all in an attempt to locate men and machines moving goods to the South. Then, if they could hear them and find them, U.S. commanders could task air strikes against the communists on the trail. It didn’t take long, Cockburn says, for the North Vietnamese to find a work-around. How long? It took one week. Cockburn notes that all the North Vietnamese had to do was to use cows and trucks, often running over an area of the trail multiple times to create a diversion while the real logistical effort was moved elsewhere. So simple and so effective — and relatively inexpensive. However, Cockburn says the cost of the electronic barrier for the U.S. was around six billion dollars.

This formula is repeated throughout the rest of the book. That is 1) There is a military problem 2) Someone always tries to find a technological solution, and then 3) Spends a lot of money only to find out the U.S. has made the problem worse.

Now fast forward almost sixty-years to the age of drones, and Cockburn introduces us to Rex Rivolo, an analyst at the Institute of Defense Analysis. It’s 2007 and improvised explosive devices are a major problem; they are killing and maiming hundreds of U.S. troops in Iraq. Asked to analyze the networks behind the IEDs, Rivolo, Cockburn says, discovers that targeted killings of these networks lead to more attacks, not fewer. This is because someone more aggressive fills the place of the leader who was recently killed. Rivolo would return to D.C., even getting the ear of the Director of National Intelligence, Dennis Blair, telling him that attacking high- value targets was not the right strategy — the IED networks and individuals setting them off were more autonomous then was initially thought. Going after the senior guy, Rivolo noted, was not the answer. But, as Cockburn says, nothing changed. Now people simply refer to the continous cycle of targeting and killing high-value targets as “mowing the grass.”

The idea of killing senior leaders or HVTs is not new, it’s been around for a long time (think Caesar). Cockburn, then, brings up one of the more interesting “what if’s” that military officers — or any student of military history — likes to debate. That is, what if someone had killed Hitler before the end of the war? Would the war have ended? Or would he have become a martyr and someone worse or someone better have taken his place? Cockburn tells us about British Lieutenant Colonel Robert Thornley, who argued during WWII that, no, the Fuhrer should not be killed. Thornley noted, that if Hitler was killed, his death would likely make him a martyr for national socialism. And that Hitler was often a man that “override completely the soundest military appreciation and thereby helped the Allied cause tremendously.” Therefore, the thinking went, we should let Hitler live and dig his own grave.

However, the problem with this debate is that context matters. Was it Germany in 1933? 1938? Or 1944? It matters because while Cockburn does not differentiate between the killing of a leader of a state and the leader of a terrorist network, they are indeed different systems that have different levers of power and legitimacy.

He is on firmer ground when he rightly notes how difficult it is for anyone to predict systemic effects when targeting a network. He reiterates these difficulties throughout the book. The most historical compelling case is WWII and the strategic bombing campaign. All one has to do is pick up the WWII U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey and read the fine work done by John K. Galbraith, Paul Nitze, and others. Disrupting or destroying networks from the air — in this case, Germany’s economy — was incredibly difficult. In many cases, assumptions of German capabilities or weaknesses were far from correct. And as Cockburn notes, the term “effects based operations,” namely, operations that are military and nonmilitary that can disrupt complex systems while minimizing risk, was a term that was outlawed in 2008 by General Mattis while the head of Joint Forces Command.

Ultimately, the debate over drones — who should control them, what should they be used for, should the U.S. target particular individuals — will continue. It’s an important topic. There are, however, a few shortcomings in this book. One of the biggest questions that goes unanswered is this: If the U.S. should not strike identified enemies or high-value targets…then what? Do nothing? Allow a Hitler to simply remain in power? Is this not a form of moral ignorance?

The questions military planners and policy makers should ask is this: Do we understand the character of this war? And are these the right tools we should use to win this war? We should not blame a drone — or any other type of tech for that matter — for bad strategies, poor operational planning, and gooned up tactics.

Drones are the future. But we should read Cockburn’s book as a cautionary tale. We should disabuse ourselves of the illusion that future technologies will be our savior. And finally, we should not let those illusions crowd out the very difficult task of understanding our adversaries and the enduring nature of war.

Andrew Cockburn’s book is worth reading. But have your pencil ready — you’ll want to argue with him in the margins.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is a naval intelligence officer and recent graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Navy’s operational planning school, the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI. LCDR Nelson is also CIMSEC’s book review editor and is looking for readers interested in reviewing books for CIMSEC. You can contact him at books@cimsec.org. The views above are the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the US Navy or the US Department of Defense.

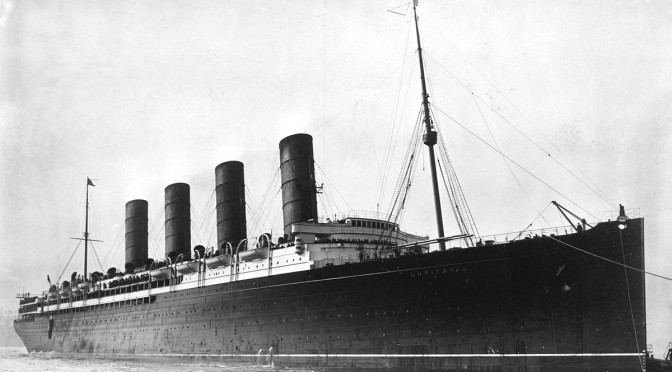

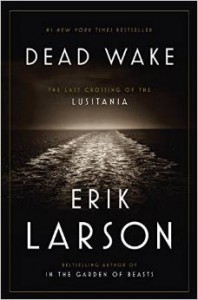

You’ll have to pick up the book and see for yourself what happens to Captain Turner, Captain Schweiger, Vanderbilt, and many others. Or if Charles Lauriat was able to save the Dickens book and Thackeray drawings. It’s worth finding out.

You’ll have to pick up the book and see for yourself what happens to Captain Turner, Captain Schweiger, Vanderbilt, and many others. Or if Charles Lauriat was able to save the Dickens book and Thackeray drawings. It’s worth finding out.