This is a post in the Personal Theories of Power series, a joint Bridge–CIMSEC project which asked a group of national security professionals to provide their theory of power and its application. We hope this launches a long and insightful debate that may one day shape policy.

There is insight in exploring the unique advantages of each domain. And the speed, reach, height, ubiquity, agility, and concentration advantages of air power allow us to focus on how best it can be used.[1] This essay will contrast the usage of air warfare via annihilation and attrition to highlight a third way, paralysis. One of the principal advantages of air power is its ability to create the temporal effect of paralysis. While it is not wholly unique from other forms of power in this capacity, it is better at it than most due to the combination of its unique advantages. Admittedly, this is a narrow look at paralysis via air power, but one that demands a point of departure from previous conceptualizations of its factors and uses.

Defining Air Power

The definition of air power has eluded strategists since man first tasted flight. The most important aspect of defining is that we must avoid conflation with niche capabilities, missions, or even processes that are related to its practice. “To be adequate,” as Colin Gray suggests, “a characterization or definition of air power must accommodate, end to end, the total process that produces a stream of combat and combat support aircraft.”[2] My definition of air power is the act of achieving strategic effect via the air.[3] Air power contributes to compounded strategic effect via annihilation, attrition, and paralysis.

Categorization and Explanation

Hans Delbrück, in History of the Art of War, describes two Clausewitzian strategies of warfare. The first is focused upon the annihilation of one’s adversary. The second, exhaustion, is more circumspect in its limited aims. Both are clearly subordinate to the idea that “war is nothing but the continuation of policy with other means.”[4] Delbrück extended these into Niederwerfungsstrategie (the strategy of annihilation) and Ermattungsstrategie (the strategy of exhaustion, attrition). The former’s sole aim is the decisive battle, where the latter is understood to have more than one concern, which is a spectrum between both battle and maneuver with the aim of exhausting the adversary. Delbrück’s History suggests that neither annihilation nor exhaustion are inferior to one another, and that attrition is not the mere avoidance of battle. But he was emphatic that these strategies were subordinate and subject to the Clausewitzian general theory.[5]

While Clausewitz was, of course, focused on the land domain, air power has proven useful in both annihilation and attrition. The Desert Storm “Highways of Death” provides a useful example of the application of air power towards annihilation. And the best example of air power’s application of attrition is one where it denied exhaustion: the Berlin airlift, with over 277,000 flights in a period of 15 months lifted 2.3 million total tons of supplies. In either case, was the application of air power uniquely responsible for strategic effect? No. In both cases — and in most every case — other forms of power aided the outcome via force, or the threat of force. But outside the Delbrückian dichotomy, there is a third way for to create strategic effect — paralysis.

…the lasting effect of paralysis, like shock, is fleeting. A permanent state of paralysis is an unsustainable (and unacceptable) political objective…

The strength of air power in the combination of speed, reach, height, ubiquity, agility, and concentration also enables a fleeting form of influence in paralysis. This strategic categorization is analogous to the tactical categorization of firepower, maneuver, and shock. Where at the strategic level firepower is exhaustive and maneuver is destructive, shock seeks temporal paralysis. Paralysis is the aim to disrupt, disable, and degrade an adversary’s physical, mental, and ultimately moral capacities. The aim of such a strategy is never an end in itself; it merely seeks to minimize destruction without precluding such action.[6] Thus, the lasting effect of paralysis, like shock, is fleeting. A permanent state of paralysis is an unsustainable (and unacceptable) political objective, and its diminishing strategic effect is reinforced by empirical examination of history. This straightforward admission occurs naturally because adversaries are not inanimate objects subject to one fell swoop, but adaptive duelists constantly seeking advantage against one another.[7]

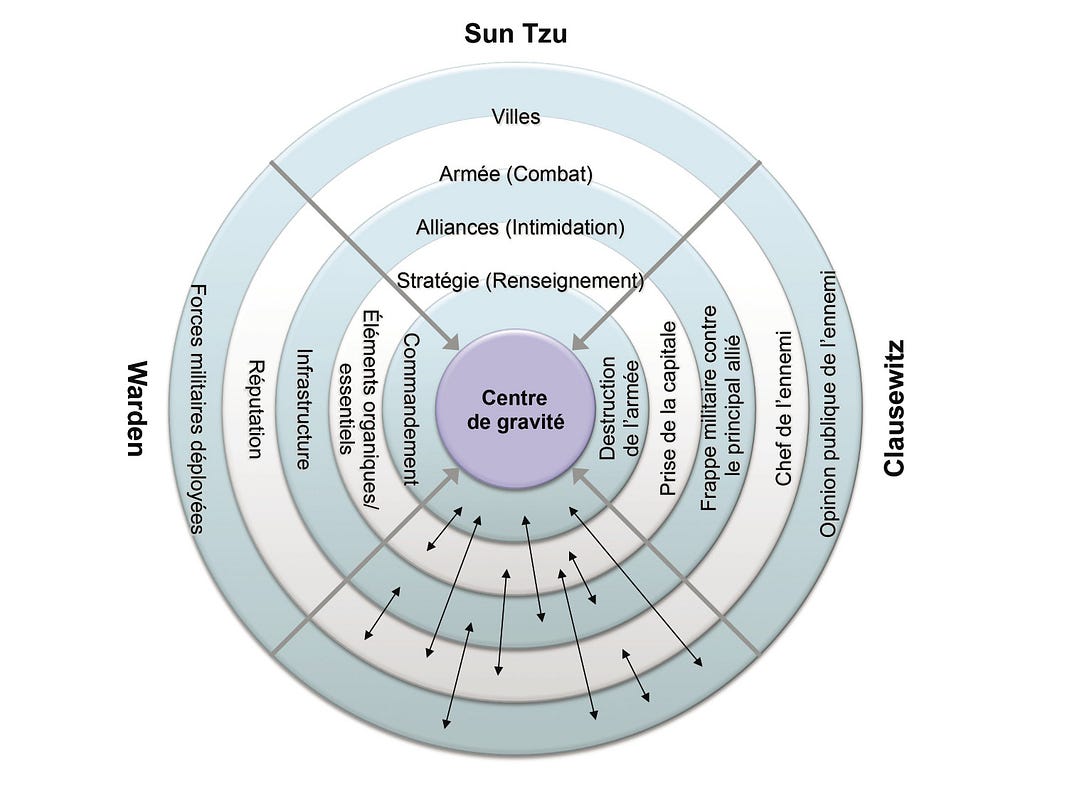

Whether air power is seeking to influence non-cooperative centers of gravity via an overwhelming tempo and variety of action,[8] or complicate the adversary’s “connectedness” by seeking a degree of isolation between its leadership, organic essentials, infrastructure, population, and fielded forces,[9] paralysis has always lacked in attaining or achieving control.[10] However, this does not preclude strategies of temporal paralysis as essential precursor to, or pivot between, the strategies of annihilation or attrition where control can ultimately be achieved. In this manner, paralysis has shown some cumulative merit in exacerbating the cognitive problem posed to an adversary because it attacks their ability to understand the character of the threat they face.[11]

Paralysis and the Laplacian Fallacy in Real War

Information and knowledge are imperfect and outcomes are not predictable. This thought contrasts Pierre Simon de Laplace, who by extension of Sir Isaac Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy suggested that the motion of heavenly bodies were mechanistic and determined completely by physical law. If you knew where one object was, you also knew where it was going in a predictable manner. Such Laplacian science cannot be effectively extended to war, as war cannot be mechanistically engineered.[12] The Clausewitzian axiom of general friction, that which “makes the apparently easy so difficult,” cannot be wished away by mechanistic approaches to war.[13]

The proper approach in seeking paralysis acknowledges the sub-optimal character of complexity, where simplicity is favored over ideals of greater effectiveness. Through this approach, one refuses the lure of the silver bullet or the bolt from the blue, but exchanges these for a more humble magnification of the adversary’s friction via mismatch, deception, disruption, and overload. The proper foundation of temporal paralysis is built upon the proposition that “actions taken to drive up the adversary’s friction are as vital to success as those taken to minimize your own.”[14]

The temporal advantage of paralysis is subjective to context and tied to chance, but not withstanding these practical limits, it is still extremely useful for transitioning to a complementary strategy of either annihilation or attrition, or both in parallel. This is why air forces have become accustomed to being the major — although not the sole — military force in garnering the strategic initiative in campaigns (or Phase II operations in doctrinal parlance of the American way of battle). Whether the outcome of that phasing construct is to compel de-escalation via the threat or use of additional joint force, or transition to the assertion of a degree of control via other forces as described above, it is still a priceless strategic advantage to have control of the air. Without a degree of control of the air, as a necessary but solely insufficient condition, escalation dominance is stunted and the final strategic outcome placed at risk.[15]

The ultimate consideration for deciding upon a strategy of paralysis via air power is whether or not it is prudently feasible for use. In at least two situations, it is not.

Anticipation of Paralysis

The ultimate consideration for deciding upon a strategy of paralysis via air power is whether or not it is prudently feasible for use. In at least two situations, it is not. In those contexts where center of gravity analysis is counterproductive or made counterproductive and when your war aims are mismatched against an adversary seeking an unlimited aim.

The former becomes problematic when the concept of the center of gravity becomes as Antullio Echevarria suggests, “an article of faith.” This is further exacerbated when disagreement occurs on the basis of epistemic rationality, which is logic founded on faith, typically from doctrinaire point of view. Finally, these problems are further compounded when a truly mechanistic approach is taken in center of gravity analysis that is tantamount to a “center of critical capability” analysis.[16]

The latter is problematic for paralysis on an empirical basis. Paralysis has typically performed poorly in protracted, internecine, and civil wars. One needs look no further than the recent counterinsurgencies to grip the truth of this. In these examples of war the “centers of conflict themselves tend to remain highly dispersed and deceptively diffused,” according to Echevarria, where under “such conditions, time often benefits the less technologically sophisticated adversary.”[17] As discussed above, such forms of war tend to obscure the true character of the threat sufficiently to mitigate the effectiveness of paralysis.[18]

Conclusion

While there are few truly unique aspects of domain-specific forms of power, each form has advantages that make it exceptional from others. For air power, that is speed, reach, height, ubiquity, agility, and concentration, which combine to provide it exceptional flexibility and versatility. While air power has demonstrably contributed to strategic effect via the strategies of annihilation and attrition, it has also done so via temporal paralysis. However, this transitory strategy is not conferred unlimited agency. Rather, temporal paralysis via air power is always subject to context and must never be applied mechanistically. It should be prudently avoided in cases where the adversary seeks unlimited aims. Finally, temporal paralysis is not inferior to its kindred strategies of war, annihilation and attrition.

[1] Colin S Gray, Airpower for Strategic Effect (Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala.: Air University Press, Air Force Research Institute, 2012), 280, 281, accessed September 19, 2013.

[2] Colin S. Gray, Explorations in Strategy (Westport, Conn.; London: Praeger, 1998), 63.

[3] According to Colin Gray in The Strategy Bridge, “Strategic effect refers to the consequences of behavior upon an enemy. The effect can be material, psychological, or both.”

[4] Carl von Clausewitz, Michael Howard, and Peter Paret, On War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 69.

[5] Gordon Alexander Craig, “Delbrück: The Military Historian,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), 341–342; Clausewitz, Howard, and Paret, On War, 87, 594, 607–608, 610.

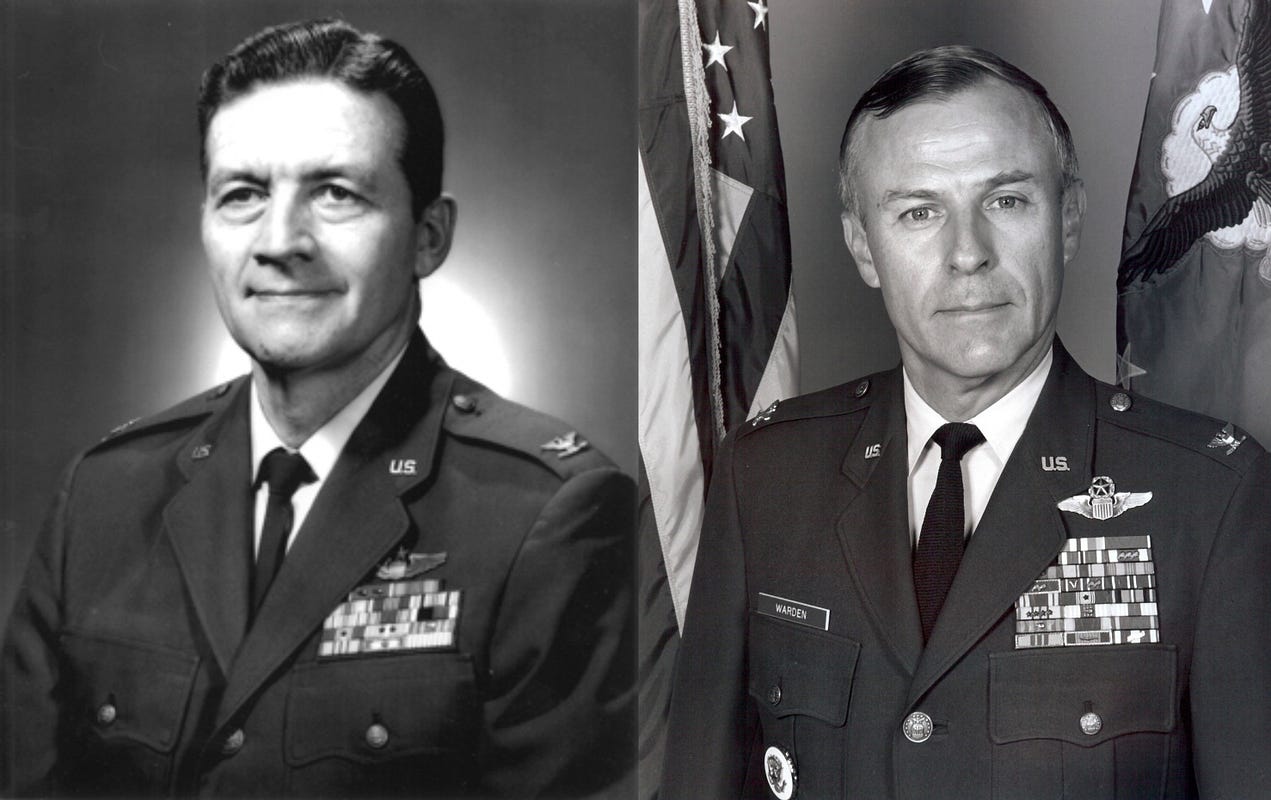

[6] David S. Fadok, “John Boyd and John Warden: Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis,” in The Paths Of Heaven: The Evolution Of Airpower Theory, ed. Phillip S. Meilinger (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 1997), 359, accessed February 6, 2014.

[7] Clausewitz, Howard, and Paret, On War, 75, 77, 79.

[8] Fadok, “Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis,” 363–370; Frans PB Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (Routledge, 2006). Fadok, “Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis,” 363–370; Osinga, Science, Strategy and War.

[9] Fadok, “Airpower’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis,” 370–379.

[10] Antulio J. Echevarria, “Fusing Airpower and Land Power in the Twenty-First Century: Insights from the Army after Next,” Airpower Journal (Fall 1999): 69. Ibid.; J. C. Wylie, Military Strategy: A General Theory of Power Control (New Brunswick, N.J.,: Rutgers University Press, 1967), 23–29, 42–48, 71; Gray, Airpower for Strategic Effect, 74.

[11] Lukas Milevski, “Revisiting J.C. Wylie’s Dichotomy of Strategy: The Effects of Sequential and Cumulative Patterns of Operations,” Journal of Strategic Studies 35, no. 2 (January 18, 2012): 236.

[12] Barry D. Watts, The Foundations of U.S. Air Doctrine: The Problem of Friction in War (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University, December 1984), 106–107, 109, 110, accessed September 1, 2013.

[13] Clausewitz, Howard, and Paret, On War, 119–121.

[14] Osinga, Science, Strategy and War, 166–172; Watts, The Foundations of US Air Doctrine, 119–121.

[15] Gray, Airpower for Strategic Effect, 284–285.

[16] Antulio J. Echevarria, “Clausewitz’s Center of Gravity Legacy,” Infinity Journal, Clausewitz & Contemporary Conflict (February 2012): 5–7.

[17] Echevarria, “Fusing Airpower and Land Power in the Twenty-First Century,” 69.

[18] Milevski, “Revisiting J.C. Wylie’s Dichotomy of Strategy,” 236, 240.