By LCDR Mark Munson, USN

Introduction

Between November 1921 and February 1922, representatives from nine nations assembled in Washington, D.C. to discuss security issues in the Asia-Pacific region and naval disarmament.1 The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) played a vital role for the American organizers of the conference by collecting information and publishing intelligence products that supported the U.S. negotiators and enabled them to achieve American diplomatic objectives. While the Conference has a poor historical reputation because it failed to prevent a naval arms race leading up to the Second World War, its more modest achievements provide a case study in successful diplomatic intelligence, with ONI’s support to the negotiating effort demonstrating the importance of intelligence expertise in maritime issues.

A Bold Proposal

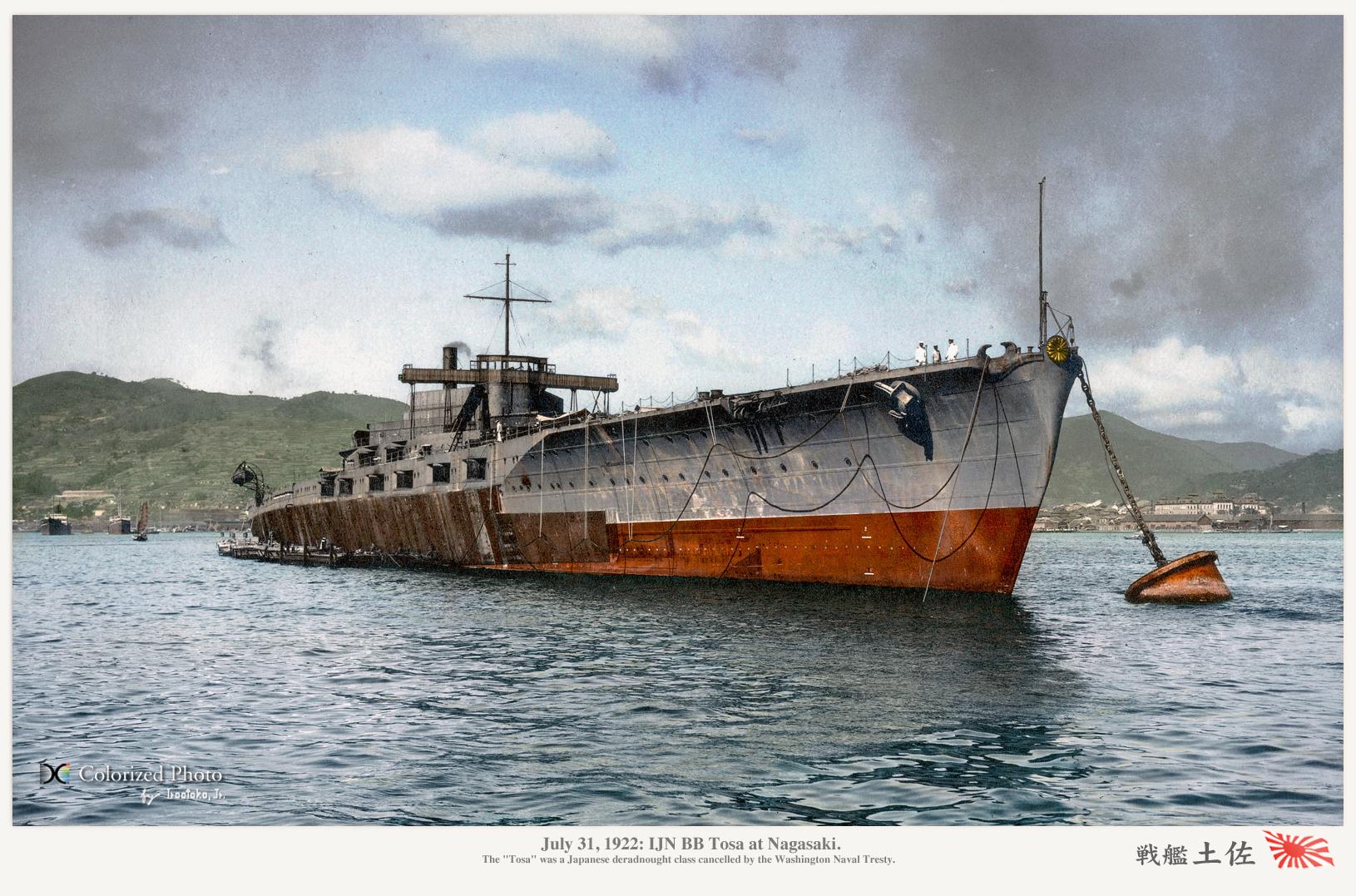

When the Harding administration’s Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes opened the Washington Conference by announcing the dramatic reversal of the U.S. Navy’s expansion, which had dated back to the beginning of the turn of the century and accelerated during the First World War, his statement “shocked the delegates by calling for a ten-year naval construction ‘holiday,’ with force ratios fixed at a level of 10-10-6 for the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. This proposal meant scrapping large portions of the American fleet, constructed as part of the 1916 expansion program, and the mid-construction cancellation of all ships funded by the 1918 Navy expansion bill.”2

By announcing a willingness to slash the American fleet, Hughes hoped to use diplomacy at the conference to further U.S. aims in East Asia and Western Pacific, with goals including “naval disarmament; a new security structure that replaced the Anglo-Japanese alliance; and the enshrinement of the Open Door policy into international law.”3 Hughes’ “surprise” proposal stunned even the head of the British delegation, former Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, forcing him “to define his country’s policy literally as he sat waiting to reply.”4

Despite being surprised by Hughes’ opening remarks, the U.K quickly saw the conference as an opportunity to realize its own strategic objectives. By the early 1920s, much of the Royal Navy, built during “the burst of warship construction before and during 1914–18, and the limited construction of the 1920s,” was now “obsolete and needed to be replaced.”5 Unlike before the war, when the Royal Navy only had to maintain superiority against the Germans, continued supremacy afloat would require a fleet “equal to that of the Japanese navy plus the next largest European navy.” With a decrease in British shipbuilding capacity eroding its status as the global maritime hegemon, a pause in the naval arms race would help the Royal Navy’s keep its numerical advantage.6

Fusing Intelligence and Diplomacy on Naval Arms

ONI was founded in 1882 and already served as “the main provider of data on foreign fleets” for U.S. policymakers on the eve of the conference.7 Just as with the rest of the U.S. Navy, the First World War had led to a significant expansion of ONI manpower, swelling to 306 reservists and 18 civil servants by 1918.8 ONI’s mission was to collect “political, military, naval, economic, and industrial” information, to “analyze, classify, summarize, and make available” that information, and to disseminate it “systematically throughout the naval service.”9

Following the war however, ONI was quickly reduced to a force of 42 by 1920.10 With funding allocated to the naval attaches providing the bulk of ONI’s reporting which was now “ridiculously small” and insufficient to support diplomatic life abroad, “appointments were often based on personal wealth rather than qualifications.” In spite of this reduced attaché force, however, headquarters was still faced with a “mass of undigested and unclassified material that started to accumulate.”11 Even “the few attaches left after postwar demobilization” were still diligently able to “interview local officials, peruse public papers, and assemble newspaper clippings” in quantities great enough to leave piles of information unexploited.12 ONI’s struggle to perform its core duty of collecting and analyzing data on foreign navies after the war was also exacerbated by its assumption of additional domestic duties including “monitoring subversive activities that alien nationals were planning to undertake on American territory.”13

To support U.S. negotiating efforts at the conference, “ONI was assigned to provide numerous statistics, graphs and charts on the comparative tonnage of the world’s navies.”14 ONI anticipated this tasking, with the Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI), Rear Admiral Andrew T. Long, having ordered “all attaches to collect local opinion concerning a possible naval limitations conference” to drive analysis in which “ONI staff prepared specifics on foreign naval expenditures, building programs, and existing warships.”15 Commander William W. Galbraith of ONI explained “it is desirable to know, as far in advance as possible, the probable plan of action on the part of the other representatives together with some insights into the instructions given to the delegates by their governments.”16

U.S. Navy attaches swung into action. The former DNI, Rear Admiral Andrew Niblack, then serving as the naval attaché to Great Britain, mailed back press clippings and even met King George V, “but characteristically found the conversation disappointing” as “the Prime Minister is the important factor in the upcoming conference.”17 Despite being close allies during the war, Anglo-American tensions were barely concealed as the conference began. British leaders had wanted a preliminary session before the main event to coordinate diplomatic aims between the two allies, but were left disappointed by U.S. reluctance. The international acclaim that had hailed President Harding from around the global after he announced the conference also irritated British leaders.18

Other ONI-sponsored intelligence collection took place elsewhere in Europe. The attaché in France provided “French disarmament data and photographs of prospective Gallic delegates,” and U.S. Navy personnel in Berlin “polled members of the Inter-Allied Control Commission, discovering a common fear of Japanese militarism.”19

With the conference agenda focused on East Asia, the U.S. Navy and conference negotiators particularly valued intelligence on the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). U.S. naval attaches in Tokyo relied heavily on open source collection, including the English and Japanese-language presses, and the Japanese Navy’s professional publications or speeches by naval officers when available. When possible they “cultivated a variety of personal sources who often supplied valuable information on Japanese naval affairs out of friendship or after consuming too much alcohol,” including “Japanese friends, foreign technical experts, or travelers who might have passed through a sensitive area,” or what they could trade from foreign services such as French or Chinese intelligence.20 Their reporting addressed topics such as “the future of China, Pacific fortifications, naval ratios, and Japanese claims to formerly German territory.”21

American collectors in Tokyo supported the negotiators with “reports by telegram at a rate of over one thousand pages per month,” complementing the efforts of the U.S. ambassador to Japan, who sent the American delegation at the conference a “daily ‘Confidential’ report of Japanese press discussions, analyses of political leaders, and detailed commentaries.”22

The intrepid naval attaches also reported on Japanese politics, an arena in which liberal groups advocating “pacifism, anti-militarism, and support for disarmament” were increasingly active.23 Understanding these fractures in Japanese political life was important, as they would drive “the degree of autonomy” that Admiral Kato Tomosaburo, Japan’s lead negotiator and Navy Minister, would have during the negotiations. After Prime Minister Hara Kei’s assassination “by a right-wing activist” on the eve of conference, U.S. Army intelligence reported to the State Department that “the confused political situation” would leave Kato “essentially operating without significant oversight from Tokyo.”24 This corroborated reporting that U.S. naval attaches had derived from open source information depicting “hardline Japanese naval officers as politically isolated,” therefore limiting their ability to resist “a stronger American position on naval force ratios.”25

ONI’s reporting and assessments on the Japanese Navy also included some particularly embarrassing examples of how bias can hinder analysis, with racist assumptions often prominent in its products. Delegates to the conference had “unusually high morals for a Japanese” and “unusual reasoning powers for an Oriental.”29 “Widespread inefficiency” in the Japanese fleet was caused by “a lack of mechanical genius,” a “low level of initiative and a corresponding inability to deal with unexpected situations.”30 Any threat posed by future Japanese naval aviation was unlikely according to ONI analysis, as “the Japanese is naturally unfitted for any mechanical pursuit, and for this reason great difficulty has been experienced in training aviators.”31

The Five-Power Treaty signed at the conference formalized the “5:5:3 ratio limit” which restricted total capital ship tonnage for the U.S. and Royal navies to 500,000, Japan to 300,000, and both France and Italy to 175,000 tons. The Treaty was perceived as a success at the time because the Japanese allocation was less than their initial desire for 70 percent of American/British tonnage. It also “recognized the status quo of U.S., British, and Japanese bases in the Pacific,” “secured agreements that reinforced its existing policy in the Pacific, including the Open Door Policy in China and the protection of the Philippines,” and limited “the scope of Japanese imperial expansion as much as possible.”32

Despite achieving success at the negotiating table, the U.S. did not fully exploit the pause in the naval arms race enabled by the Washington conference. Although the Treaty limited naval expansion by its British ally and potential Japanese rival, “the American Congress consistently refused to spend enough to bring the U.S. Navy up to tonnage parity with the Royal Navy.”33 Despite being allowed by the Treaty to build as many battleships as the cash-strapped Royal Navy, the actual ratio of ships built between the Royal, U.S., and Japanese navies ended up closer to 5-4-3 between the wars.34

The traditional narrative of the Washington Treaty has been that it left the U.S. Navy unprepared for the Second World War.35 Influential mid-century naval thinkers like Samuel Eliot Morison and Dudley Knox argued that the “treaty navy” was “barely prepared for war” in 1941 in terms of fleet size, and that the treaty allowed political leaders to justify neglect of U.S. bases in the Western Pacific like Guam and the Philippines.36

Regardless of whether the Treaty resulted in a small, crippled navy at the start of the Second World War, the efforts of ONI and its attaches “successfully accomplished an important intelligence task,” particularly against Japan, and “reduced uncertainty for American decision makers at a key moment in international relations.”37 ONI’s quantitative work was particularly important, driving negotiations focused on “the comparative tonnage of warships and strengths of navies.” However, even at the time, ONI’s experts cautioned “that relative naval power could not be measured in exact mathematical terms nor equitable naval ratios by simple formulas.”38

Naval intelligence collectors, particularly the attaches in Japan, made use of their language training, applied both “to translate written evidence such as government documents and press sources, as well as to conduct conversations with their hosts” in the course of their daily lives. Information was collected by “visits to naval facilities and dockyards” when possible, “private U.S. citizens, who were either based in Japan or paying temporary visits,” or occasional “intercepts of radio communications.” While clandestine Human or Signals Intelligence collection may have been particularly prized, naval intelligence ultimately collected “95 percent of the information it sought” in Japanese-language open source publications.39

Despite the success ONI’s collection mission achieved against Japan, it was always hindered by “the Japanese government’s stringent restrictions on the activities and movements of foreign intelligence personnel.”40 This “shortage of reliable intelligence” resulted in an overemphasis on quantitative reporting (numbers and tonnage of Japanese Navy ships), at the expense of understanding “operational doctrine and the performance of its equipment.”41 To be fair to those collectors, the Japanese Navy’s “tight veil of secrecy” would have hindered any collection efforts,42 but the emphasis on fleet size and tonnage may have led ONI analysts to underestimate “the Japanese Navy’s determination to achieve supremacy in the western Pacific through qualitative one-upmanship.”43

The aftermath of the conference left ONI with a clear mission and requirements for future intelligence collection and production. Savvy analysts at ONI quickly realized that the Washington conference and a series of successive conferences in Geneva and London aimed at limiting the construction of smaller classes of naval vessels “blinded Americans to the need for continued naval defenses, concluding that ONI must be the vehicle to spread the warning.”44 Their task was to uncover treaty violations, assuming “that all signatories would circumvent the settlement and try to deceive the other powers.”45

Conclusion

ONI support to the conference shows the continued importance of Open Source and Human intelligence (OSINT and HUMINT, respectively), particularly when enabled by expertise in foreign languages. While much of the information that the U.S. Navy’s attaches in Japan collected was openly available, it would have remains uncollected and unexploited if the Navy had not invested in language training for those officers. Even in a digital age where information is freely available over the internet, OSINT collection may still require a properly trained collector to have physical access to freely available data and media.

The U.S. Navy’s main intelligence challenge against its future Japanese foe was not determining how many ships they had, but rather, how to develop a detailed understanding of Japanese naval doctrine and how they planned to fight a future war at sea. While the Treaty made counting the Japanese fleet a straightforward task, Japanese secrecy, a lack of effective HUMINT placement and access (a task almost impossible for the segregated U.S. Navy’s largely all-white officer corps in pre-war Japan), and technological barriers preventing SIGINT collection stopped ONI from achieving “penetrating knowledge” of the Japanese Navy.46

Finally, ONI’s efforts in support of the conference show the importance of expertise in maritime issues to naval intelligence. Ultimately, the U.S. Navy is the only arm of the U.S. government that will always prioritize intelligence on foreign navies and the global maritime system. While maritime intelligence is not always valued by government leaders and the intelligence community as whole, when a situation arises in which maritime expertise is needed by national decision-makers, they will expect naval intelligence to have the answers they need immediately.

The Washington conference may have proved a long-term failure in terms of curtailing the growth of the navies that fought in the Second World War, and a low point in terms of American isolationism and the abandonment of sea power as a national security strategy. For ONI however, it provided an opportunity to apply a variety of intelligence disciplines in support of national diplomatic objectives.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a naval officer assigned to Coastal Riverine Group TWO. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

[1] The U.S., U.K., Japan, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, and China participated in the conference. The “Nine-Power Treaty” dealt with the interests of western nations and Japan in China. The treaty addressing naval arms control was the “Five-Power Treaty signed by the U.S., U.K., Japan, France, and Italy. The “Four-Power Treaty” was signed by the U.S., U.K., Japan, and France, replacing the 1902 alliance between the U.K. and Japan, and attempted to accommodate those nations’ interests in East Asia. See “The Washington Naval Conference, 1921–1922,” Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State, accessed 28 July 2017, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/naval-conference

[2] Eric Setzekorn, “Open Source Information and the Office of Naval Intelligence in Japan, 1905–1920,” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 27, (2014): 379.

[3] Paul Welch Behringer, “‘Forewarned Is Forearmed’: Intelligence, Japan’s Siberian Intervention, and the Washington Conference,” The International History Review 38:3 (2016): 368-369.

[4] John Ferris, Issues in British and American Signals Intelligence, 1919-1932 (Fort Meade: NSA Center for Cryptologic History, 2015), 44.

[5] Joseph A. Maiolo, “Anglo-Soviet Naval Armaments Diplomacy Before the Second World War,” English Historical Review 123:501 (2008): 352.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Douglas Ford, “U.S. Naval Intelligence and the Imperial Japanese Fleet During the Washington Treaty Era, c. 1922-36,” The Mariner’s Mirror 93:3 (August 2007): 284.

[8] Wyman H. Packard, A Century of Naval Intelligence (Washington: Department of the Navy, 1996), 13.

[9] Ford, 284.

[10] Packard, 14.

[11] Ford, 284.

[12] Jeffery M. Dorwart, Conflict of Duty: The U.S. Navy’s Intelligence Dilemma, 1919-1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983), 20.

[13] Ford, 284.

[14] Ibid., 285.

[15] Dorwart, 20.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Erik Goldstein, “The Evolution of British Diplomatic Strategy for the Washington Conference,” in The Washington Conference, 1921-22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor, ed. Erik Goldstein and John Maurer (Ilford: Frank Cass, 1994), 18-19.

[19] Dorwart, 20.

[20] Setzekorn, 373-374.

[21] Ibid., 377.

[22] Ibid., 380.

[23] Ibid., 378.

[24] Ibid., 379.

[25] Ibid., 369.

[26] Ford, 285.

[27] Ibid., 292.

[28] Ibid., 290.

[29] Dorwart, 20.

[30] Ford, 281.

[31] Ford, 293.

[32] “The Washington Naval Conference, 1921–1922,” United States Department of State.

[33] Maiolo, 355.

[34] Ferris, 44-45.

[35] Michael Krepon, “Naval Treaties,” Arms Control Wonk, accessed 28 July 2017, http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/403364/naval-treaties/.

[36] John Kuehn, “The Influence of Naval Arms Limitation on U.S. Naval Innovation During the Interwar Period, 1921-1937” (PhD diss., Kansas State University, 2007), 17-18.

[37] Setzekorn, 382.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ford, 286.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid., 281.

[42] Ibid., 285-286.

[43] Maiolo, 375-376.

[44] Dorwart, 22.

[45] Ibid., 24-25.

[46] “Navy Strategy for Achieving Maritime Dominance: 2013-2017,” 7.

Featured Image: Scene at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania, December 1923, with guns from scrapped battleships in the foreground. (Wikimedia Commons)