By CDR Paul W. Viscovich, USN (ret.)

Vale la pena (“It is worth the effort”) was the motto of Naval Special Warfare Group EIGHT when it was stationed in Panama some 30 years ago. It was an appropriate philosophy for a tip-of-the-spear warfighting unit, and they lived up to it in operations throughout the U.S. Southern Command area of responsibility. Can these SEALs teach us how to prioritize warfighting, and can their unit-level lessons be applied throughout the fleet?

In order to prioritize one thing – warfighting – it is necessary to diminish the importance of conflicting requirements. Due to the unique nature of their mission, and with the unyielding support of their NAVSPECWAR chain of command, the SEALs are largely insulated from the administrative distractions that bedevil the other warfighting communities. Their maintenance, training, and security programs are all consciously vectored toward supporting their one priority – providing warfighting capability.

Two things allow the SEALs to accomplish this. First, their entire community is culturally focused on warfighting. Second, their senior leadership is uncompromising in eliminating anything that distracts from this priority.

This leadership doctrine is at such variance from the rest of the Navy that any immediate attempt to apply this model on a fleet-wide scale will fail. The eight-decade absence of deadly conflict with an enemy of equal or superior capability has eroded the warrior ethos in generations of naval officers and senior enlisted leaders. Its absence has caused perverse incentives to metastasize, such as an administratively-obsessed culture that often defines excellence in terms of passing rote inspections, and scripted drills that mask warfighting deficits but make for positive reporting. Although individual commanding officers may strive mightily to create a warfighting focus within their units, the chain of command’s overriding insistence that they check all the superfluous administrative boxes will continue to doom their efforts and overwhelm the time of warfighters on the deckplate. At best, unit leaders can only put warfighting first on the margins of an already thinly-stretched crew and schedule. Whether aviators, submariners, or surface warfare officers, U.S. Navy flag officers are now largely trained, groomed, and selected to perpetuate this bureaucracy that is top-heavy with administration.

In this environment, almost any program to refocus the fleet on warfighting is likely to be little more than window dressing. An institutional initiative to put warfighting first could easily result in even more required record-keeping and reporting on top of what has been accumulating for decades. Today’s culture will self-perpetuate until some major calamity pushes the fleet into an existential fight, and finally forces the Navy to sharply consolidate its priorities toward warfighting.

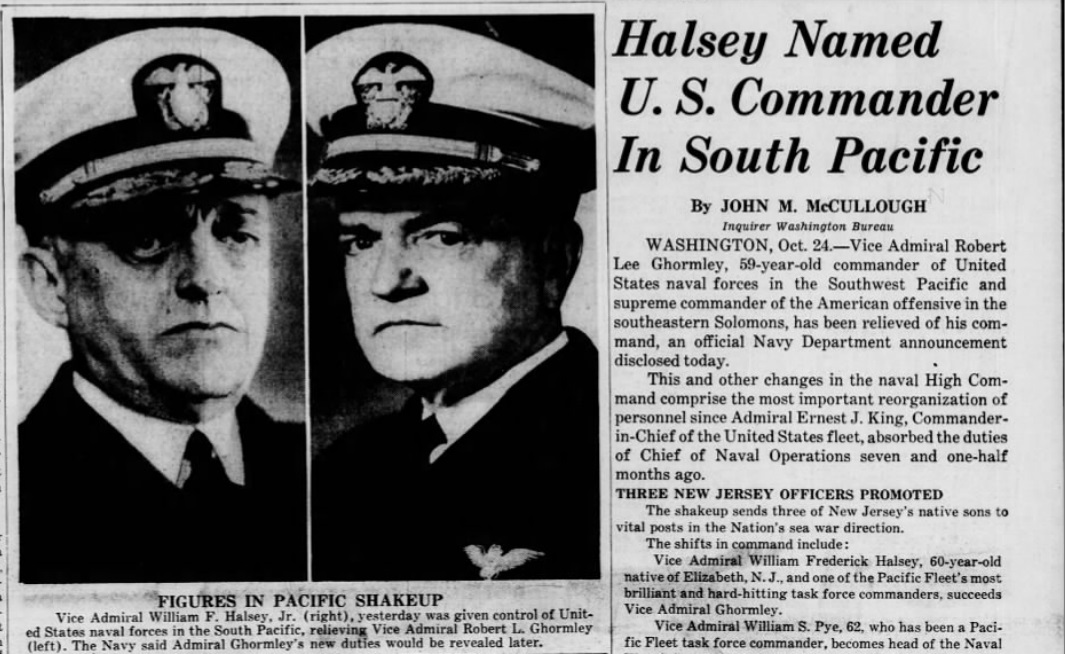

The crucible of combat quickly shines a light on incompetence. It is common for warring great power militaries to fire and replace numerous commanding officers after poor combat performance, whether they be unit-level leaders, or senior flag and general officers. Those who more effectively put warfighting first in peacetime may be the Halseys that replace the Ghormleys. The Navy should take great care to learn the difference before its next war, and develop better warfighting-focused incentives and criteria for promotion and fitness reporting.

If senior Defense Department civilian and military leaders do not seriously convert organizational priorities toward warfighting, any lower-echelon attempt to refocus fighting forces on their core responsibility will achieve only marginal effect. Senior leaders must grasp how deckplate-level reality has become suffocated by miscellanea accumulating from decades of poorly prioritized requirements. Senior leaders must take decisive ownership of the problem and return enough time and focus to warfighters so they can truly put warfighting first.

Paul Viscovich is a retired Commander and Surface Warfare Officer with 20 years active service. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1975 and earned a Master of Sciences degree from the Naval Postgraduate School in 1987. From 2013-2021, he authored a monthly political column published in a south Florida magazine, currently writes a current events newsletter on Substack.com, and is working on an anthology of short stories, many with a nautical theme. He lives with his wife Christine in Weston, FL.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Sept. 19, 2016) The Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Benfold (DDG 65) fires a standard missile (SM 2) at a target drone as part of a surface-to-air-missile exercise (SAMEX) during Valiant Shield 2016. (U.S. Navy photo illustration by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Andrew Schneider/Released)

Not long after I took command of VFA-131 I walked into maintenance control and announced that the squadron would no longer prepare for inspections. As a former maintenance officer I saw how the senior enlisted not only devoted hours to such preps, they also tended to gundeck the required records. I was determined to stop all that. Moreover, I wanted the troops to focus on producing safe, combat ready birds. I was fully prepared to forego glowing reports and awards. I was serious about our training matrix and got into hot water with the CAG when I opposed his policy of not letting Hornets fly CAP, which was part of our matrix. This may be just my experience, but I think COs must be prepared to fight “city hall” to get their units truly combat ready.

Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts, Captain Rubel.

In my experience, COs with such a tactical focus as yours are an exception to the rule. It was my great fortune to serve as XO for such a captain. But unless you are relieved by a like-minded successor, the command defaults to an administrative excellence and Battle “E” orientation, and the cycle continues. Absent a total change in the thinking and priorities of our most senior leadership and a willingness to purge all programs and personnel which do not directly and demonstrably support excellence in warfighting, the efforts of commanders such as you and the subordinates you inspire will not change the contemporary corporate culture. At least not until one of your protegés promotes to the top of the pyramid and brings an entourage of his disciples with him.

“… can their unit-level lessons be applied throughout the fleet?”

No, and unequivocally no.

First for the practical reason: Admirals don’t run unit-level groups and are practically clueless as to what the requirements are for any unit-level group to become highly-effective.

Now for the political reason. No Admiral of a failing system is going to sit in judgement of other Admirals until something truly disastrous happens. And the indisputable proof of that is in the training boondoggles that led to the Fitzgerald and McCain accidents … and a dozen others I could name.