By Matthew Merighi

Join the latest episode of Sea Control for a conversation with Captain Klaus Mommsen (ret.) of the German  Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.

Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.

Download Sea Control 138 – Russia’s Navy: Potemkin or Power Projection?

The transcript of the conversation between Captain Mommsen (KM) and guest host from the University of Kiel, Roger Hilton (RH), begins below. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. Special thanks to Associate Producer Ryan Uljua for helping produce this episode and Assistant Producer Valtteri Tamminen for creating the transcript.

RH– Hello CIMSEC listeners and readers, my name is Roger Hilton, a nonresident academic fellow for the Institute for Security Policy at the University of Kiel, welcoming you all back for another Sea Control episode. Before diving into our material today, it is my pleasure to introduce our listeners to the Kiel Seapower Series, with a wealth of information and resources, be sure to visit their website at kielseapowerseries.com for all your information on maritime security.

If you are an enthusiastic follower of international relations, or even a fair weather observer, it is hard to ignore the success being heaved on Russia’s current foreign policy, and of course it’s grandmaster, President Vladimir Putin. From their cyber prowess, to their acute intervention in the middle east theater, it seems the Kremlin is unbeatable at the moment. Amidst the blitz of publicity, any survey of Russia’s power projection would be incomplete without a survey of their naval forces.

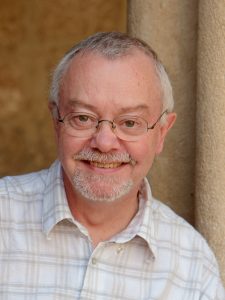

Here with us today is retired German Navy Captain Klaus Mommsen, who will help us establish if Russia’s navy is a force to advance their great power aspirations, or merely a Potemkin projection. His contribution in the Routledge Handbook of Naval Strategy and Security provides a succinct description of Russia’s naval history, as well as an analysis of its strengths and weaknesses.

Captain Mommsen is a graduate of the Military Academy of the German Armed Forces as well as the Canadian Command and Staff College, after which he spent most of his career in naval intelligence, both as an analyst and in leading staff functions. He has also contributed to Marine Forum, the monthly magazine of the German Maritime Institute for 25 now. Finally, he’s also the author of a book on the history of Israeli Navy. Klaus, it’s a pleasure for you to be with us today.

KM– Good morning Roger, thanks for having me on your podcast.

RH– Based on their impact and growing geopolitical influence abroad, your piece in the Routledge Handbook contrasts this with a sobering perception of their naval capabilities, both in piece and war time, and frankly provides a bleak outlook for the future. History confirms that Russia’s stage prop is a mixture of a siege mentality perception toward foreigners and the need to dominate their near abroad to guarantee their security. Which is manifested with the use of hard power tactics as we’ve seen recently in Georgia and Ukraine? And before diving into more detail, could you briefly describe how the current military maritime order is divided?

KM-Well the Russians can certainly navigate beyond the green water which means inland waterways or brown water which means coastal waters, to the blue oceans, so they have a blue water capability that makes them a blue water navy. They can send task groups or forces all around the world, even come back to combined exercises with friendly navies such as India. So they have a global reach but they do not have the capabilities for power projection. Russia in my opinion, and to my definition, is not a sea power, not using the navy to protect its global trade routes, its sea line of communications outside its regional borders, and with the exception of Syria, has never used the sea beyond mere presence and to actively intervene in conflicts abroad.

RH– When you talk about pure power projection, obviously the only country that has true global reach is the United States. But within this different category you have multi-regional power projectors, like Russia, India, Italy, Spain, and Brazil. Could you go into a little bit more detail about multi-region power projection?

KM– The Russians are forced to be a multi-region power projector because Russia spans several regions, but the are not connected regions. Some people would argue that the recent deployment of the carrier Kuznetsov, was a power projection from the sea. It was not. It was totally redundant. Ground based aircraft did the work. They flew much over 10,000 sorties over Syria, but the Kuznetsov only a couple of hundred during the whole three months.

Just take the sortie rates of other navies, aircraft carriers, the new U.S. Navy carrier Ford will allow for a sortie rate of up to 207 sorties a day. The Nimitz in one exercise managed 197, the French carrier Charles de Gaulle is capable of 100. The Kuznetov, some analyst say that they might generate up to 30 sorties a day and not on a sustained level.

Other navies are operating globally and are also during power projection, the French do it, the British Royal Navy does it, the Indian Navy is just a regional navy, they are not really operating out of region. The same goes for some navies in South America which have blue water capabilities just because they have to deal with large areas of the Southern Atlantic or the pacific. That is not for the region, and not for the Russians.

RH- Klaus, thank you so much for actually distinguishing that a lot of their power projection in Syria was as a result of their Air force sorties and not their naval capabilities. It is often lost in the discussion. Can you quickly get into the organization of the Russian Navy? Specifically what are its priorities and areas of interest, and its current capabilities?

KM– It is currently organized into four fleets. The Northern Fleet in the Kola Peninsula, the Baltic Fleet based in the Gulf of Finland and in the Kaliningrad oblast. The Black Sea Fleet focused on Sevastopol, in now Russian Crimea and Novosibirsk and the Pacific Fleet in Vladivostok and Petropadstok. And then they have a fifth fleet which basically is a flotilla, they call it the Caspian Sea Flotilla, which is locked in the caspian sea. There are some inner water ways where they can transfer ships back and forth, but it is basically not out of region. The current focus is on the Arctic, with its vast resources, and on Western Europe and NATO. And in the southwest with the Black Sea being a jumpboard to the Mediterranean and the Middle East. That is also the only area where Russia sees wide possibilities to strengthen it political or military influence.

RH- With that goal in mind of strengthening its influence, what kind of hardware and capabilities do the four fleets and the Caspian flotilla utilize right now to pursue their objectives?

KM– They have very old warships and weapons systems, and very modern ones. Most of their arsenal is more or less outdated with many ships 30 or more years old. Modernization efforts are underway with emphasis on blue water capable vessels, such as frigates and submarines, which also are useful in regional waters.

The future sees new destroyers, cruiser refurbishment and even a new aircraft carrier, but we are talking decades to come. Progress is slow. The weapons systems are being modernized, currently they have new missiles in their arsenal. We all noticed the test firing and demonstration of their Kalibr cruise missiles from the Caspian sea or the Mediterranean to Syrian targets.

Generally the progress of modernization is very slow, and you mentioned Potemkin. The government announces huge progress with more than 80 warships commissioned in 2016. That was meant for the Russian people, with more than 70 of those warships being auxiliaries such as harbor tugs or diver support vessels, small boats. And some tend to just mention numbers in comparing navies, say they have 11 aircraft carriers vs just one. They have 60 destroyers, the Russians have just eight, yet these numbers do not count, it is the capabilities that count.

RH– Again Klaus, an excellent observation that it is not the numbers that are important as much as the modernization and capabilities at the disposal of the Russian navy. Moving on to their naval history, anyone who’s ever visited Russia knows that it’s known for its harsh winters and frozen waterway paths which proves to be a strategic disadvantage. Could you go into detail a little bit about how the geography has vexed the composition of the Russian Navy?

KM- The whole geography makes Russia landlocked. It is only a few months where sea passage is viable. Under St. Peter, the only viable seaport was Arkhangelsk at the White Seas, accessible only a few months a year. With inland trades, very little developed, you can imagine that no one is going by horse from Moscow to the far east. Czar Peter naturally focused on sea trade. He founded St Petersburg, he saw the Baltic as an access route to sea trade. He had a large commercial fleet, and a new Baltic sea port built at St Petersburg to and to protect these new assets he established a Russian Navy. By the way that is exactly what Mahan had in mind, he said to be a sea power you have to have a commercial fleet and a navy to support it, protect it. So Czar Peter followed Mahan’s aspect.

And going further down in history, 50 years later, Catherine looked south. She secured Crimea, founded Sevastopol, and got an access to the Mediterranean. Ice free all year, though she never managed to get hold of the Turkish Strait, we will come to that later. In 1860, Vladivostok in the far east was added and became a major Asia hub for trade. And only in 1916, Murmansk, mostly ice free due to the gulf stream, was available to the Russian commercial fleet and naval fleet. All these naval fleets created at these directions, to the west, to the north, to the southwest to the east, fulfilled merely regional missions. It’s huge distances forbade any combined operations, they tried it once during the Russo-Japanese war but failed, they deployed the Baltic Fleet all the way to Japan.

RH– I mean there is no doubt that it was a cataclysmic failure for the Russian Navy in the early 20th century when they embarked on that mission. We’ve established the principal reason for the expansion of the Russian Navy was primarily financial gain under Peter. On the Treaty of Montreux which regulated the Turkish straits, could you go into detail a little bit about why this is so important and how it impacts Russian Navy posture?

KM- Some people said that the Treaty of Montreux gives the Turkish control of the Turkish straits. It controls whoever is going in or out of the Black Sea, and regulates the passage of warships. It also restricts the numbers and times that goes for non-Black Sea residents as well as those inside the Black Sea. So Russia also has limitations in deploying its fleet. For example, no submarines may pass submerged, and no aircraft carriers are allowed to pass, even Russian ones. Which by the way lead to the designation of the Admiral Kuznetsov, which was built in the Black Sea in Ukraine, as a flight deck cruiser, not an aircraft carrier. Right now, the Russians stick to the Treaty of Montreux, even though it is restricting their own moves. They see it as a tool to protect their own territory. It is more important to them to keep others out of the Black Sea than to use it for themselves for out-of-area deployments, into the Mediterranean or elsewhere.

RH– Undoubtedly Klaus, everything you mentioned is valid but it is important to also assess the redistribution of maritime power with new NATO states including Romania and Bulgaria, and obviously Georgia aggressively looking to join NATO. So it puts a lot of pressure on the Russian Navy in Sevastopol due to these geopolitical factors. One last analogy that would be interesting to listeners, is the comparison between as Rome as a land power and Carthage as a sea power. Is this an accurate comparison at all of Russia?

KM– Not really, Rome acted as a land power, but geographically it was not forced to do so. Rome had an outspoken maritime geostrategic location with the Italian peninsula dominating the Mediterranean, they could have dominated the Mediterranean but they focused on land power. Russia on the contrary is landlocked with very few access points to the open sea.

RH– It’s beneficial for you to clarify as it is an analogy that is often promoted inside of Russian media sources. Moving on to the USSR, the emergence of the Soviet Navy and its red fleet, apparently from your text did not change or waiver that much from Imperial Russia. Again what was its existential purpose moving forward?

KM– Primarily to support land forces and for securing sea supply routes and protecting the seaside flank.

RH- So like you said, even during the Soviet times, at its nascent beginning, it didn’t possess the capability to assume a more defensive posture?

KM- An offensive posture, yes, but for the navy just posture. Except for the developments of the nuclear ballistic missile submarines, the so called bastion concept, defense of the homeland was dominating and has been dominating today. Increased naval presence abroad is part of that but just that presence is not combat presence. Once in awhile they use it for political bullying.

RH- Its great you were able to bring up the bastion concept because it really reinforces Russia’s siege mentality perception of foreigners as well as their need to dominate in the near abroad. An interesting focus comes with the major changes that took place under Admiral Sergei Gorshkov who was in charge of the Soviet Navy from 1956 to 1985. Its referred to as the golden age, could you provide details or elaborate on what major reforms took place under his tenure?

KM- Some people tend to see this as the Soviet Navy, the red fleet moving from the home waters to the oceans as an offensive posture. Basically, the thought behind it was still defensive in nature, with increasing range of weapons developed, nuclear missiles, submarine launched nuclear missiles, aircraft carriers, they could not wait in home waters for the enemy to arrive there. They had to leave home waters to challenge the enemy already embarked, the enemy meaning the U.S. and NATO. This could be understood as the strengthening of offensive capabilities.

They created a deeply layered line of defense. Starting in the open Atlantic with submarines and aircraft, antisubmarine warfare aircraft and cruisers with long-range missiles. All these assets were to counter U.S. carrier strike groups and the ballistic missile submarines to keep them away, out of reach of the Russian homeland, to protect the motherland’s coasts, ports, and naval bases. The first layer out in the Atlantic, the second layer just north of the North Cape, then came the Barents Sea, and then came protection of their own ballistic missile submarines as a second strike capability, which were basically holed up in the Kara Sea in the arctic waters, out of reach for the U.S. forces.

RH– I think we would both agree that Peter the Great would be envious of Russia’s ability at this time to create such strategic depth while encountering a much more advanced western adversary. Against this backdrop, what would you suggest is the main takeaway from the USSR’s experience at sea?

KM- Their main mission was to protect the core of Russia. They had no real responsibility for maritime offensive operations. The flank protection of land operations was dominating. Offensive concepts of operations were part of the game. Submarines had to cut off NATO’s supply lines, again with the aim to favor their own land forces in Europe. In previous operations to gain the Baltic approaches, they were meant to open up lanes to the North Sea and North Atlantic and use Baltic rear facilities for logistics and repairs for ships of the northern fleet operating there. Ships like Kiev-class aircraft carriers were to facilitate quick shifts of focus in amphibious operations, just operations off the coast.

They were not meant for power projection in other reaches of the world. The overall aim was not to expand their operations to the world oceans, they were just integrating the oceans into their own homeland defense.

RH- Klaus, the last thing as we dive back into history, as they routinely say we’re entering a new Cold War. Would you say that the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 was arguable was arguably the greatest success of the Soviet Navy?

KM- It was definitely the greatest achievement in logistics operations. 86 navy civilian ships made 183 trips, transported 42,000 soldiers, and 230 tons of cargo to Cuba. That was a logistic operation. Again, they avoided military confrontation, the navy was insufficient to challenge the U.S. at sea. Especially when far away from home. So with only the nuclear option left, tThey eventually withdrew and backed down.

RH- Moving on now to the post- Soviet Navy, obviously a lot changed with its collapse and the Russian Navy was left in a dilapidated state. With the emergence of the new independent republics came the loss of basing rights, for example. What were some of the major operational consequences that the Russian Federation had to deal with as a result of the loss of basing rights and territory?

KM- They have to just look at the map to see that they lost major parts of the Baltic and Black Sea coast. In the Baltic they were driven back to the Gulf of Finland which is the most eastern part and the Kaliningrad enclave, that is all that was left. All of the Baltic state coast was gone. The same happened in the Black Sea, the Crimea went to the Ukraine and Georgia became independent. That left Russia a small portion of the Black Sea coast focused around the Novorossiysk. For two decades they made a deal with Sevastopol leasing agreements with Ukraine so they could stay and use Sevastopol in the Black Sea. What was gone also was all the shipyards in Ukraine. That was where large combat ships, including aircraft carrier,s were built. They were gone, and Russia was financially broke. The shipyard industry had completely refocused, they had no more subcontractors in former Warsaw pact states, except Ukraine which remained the sole manufacturer for gas turbines. A serious mistake to be felt after 2014.

What augmented it was the access to western technology and lack of funds, along with neglected indigenous development. More than half of their submarines were decommissioned, and large surface ships had to be laid up. They had no money to keep them afloat, no personnel to man them. Most ship engineers came from the Baltic soviet republics. They were gone out of country. They were forced to make due with a small combat corps. Just a few ships which they put all effort into keeping them combat ready. But basically they remained merely for coastal defense.

RH- There is no doubt after reading your text that after the collapse of the USSR, their competency to build ships vanished completely. But what is more exposed today I think you’ll agree is the indigenous development program and their overt reliance reliance on foreigners for both equipment and experience. Before we get into the strategic considerations and their objectives, there was a brief moment of rapprochement of former enemies joined in multilateral naval exercises. Today this is something that seems so far fetched, but maybe you can go into detail about this initiative that was taken immediately after the collapse of the USSR.

KM- The Yeltsin Russia was wise enough to see that it had no chance to survive in continuing confrontation with the west. Confrontation with the west had ruined it financially. Reagan had said that the Star Wars program had brought them to their limits and over their limits. So Yeltsin sought to engage with the west. The navies also did some programs, combined annual exercises with France, the U.K. and the U.S., where they rotated posting these exercises through the four countries. They had polar exercises with Norway, and they even joined the BALTOPS exercise, which before had been a U.S. hosted exercise for only NATO partners. They even joined NATO counter-terror operation Active Endeavor in the Mediterranean until approximately 2008.

RH- The third section of your piece talks about the strategic reconsiderations of Russia, the Russian Navy, and their motivation to get back to the oceans. You single out two seminal moments for this reformation of doctrine. One is the March 2000 assumption of the Russian presidency by Vladimir Putin and the subsequent introduction of the 2010 Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation, which put an emphasis on transport routes for energy resources. What should be known about these two elements?

KM-When Putin came to power in 2000, he first continued the friendly relationship with the west, including all the naval programs. The 2010 military doctrine was after Georgia, which was in 2008. The doctrine puts an emphasis on the arctic. Other sea lines of communication are out of reach for the Russian Navy, at least for sustained operations under real threat. They did do anti-piracy operations off the Horn of Africa, but with the emerging Mediterranean squadron, they had to skip that due to a lack of ships. Controlling sea lines of communication until today is not a mission for the Russian navy. They do not have the capabilities to do it globally. The arctic yes, because that is off their own coastline, some chokepoints possibly, but with limits to resources.

RH- What then was the overarching objective of the Putin regime’s strategic reconsideration?

KM- To paraphrase, to make Russia great again. He does not like Russia to be called a regional power with just nukes. He does not want to be junior partner in multinational U.S.-led operations or world politic. He wants Russia accepted as a superpower, also at sea on the oceans. By the way, that was the main reason for the Kuznetsov deployment to Syria. To demonstrate they have the capabilities in a conflict, Syria, that has no maritime dimension at all. Together with the Admiral Kuznetsov, the missile cruiser Pyotr Velikiy was deployed to Syria. But it was not mentioned a single time in any general staff briefings. Even the Kuznezov after flying some initial sorties, combat sorties, was totally out of reporting from general staff briefings for two months.

RH- Klaus, everything you said is very valid, anybody who was following Russia’s naval intervention must take the deployment of their aircraft carrier with a bit of salt, as photos of it around England with a tug for in the event that it would break down really demonstrated that maybe it wasn’t such a power projection tool as we thought, and how outdated it was to shoot off its planes for its sorties. Do you have any commentary about the flotillas and their less-than permanent presence far from home bases?

KM- The new flotilla concept for out-of-area presence was announced in 2012 and said it would create permanent squadrons in several places around the world. The first one was the Mediterranean squadron to be set up and commanded and controlled from the Black Sea Fleet. They had in mind that the Mediterranean squadron would be comprised of new frigates and submarines that were under construction then and were thought to be delivered and commissioned around 2014 or even earlier. They were centered around the Syrian base of Tartus for logistics. At that time they did not see the detrimental effects of the Ukraine crisis, which only developed in 2014.

And the embargoes, which combined with homemade deficiencies in naval shipbuilding, wrecked all of their ambitions for out of area deployment. Officially they even had to use other fleets to back up for the lack of the Black Sea Fleet. Northern Fleet and Baltic Fleet units had to deploy to the Mediterranean just to act with the Mediterranean squadron which did not do any operations. They just sat there with naval presence. Even the Pacific Fleet had deployed its missile cruiser Varyag for some time to be part of the Mediterranean squadron. In official statements I do not see a limited Black Sea Fleet. For them, the required use of Northern Fleet, Black Sea, Baltic Fleet, and even Pacific ships was just another demonstration of the growing capabilities for interfleet operations.

RH- Despite all of these official statements you would assume it’s very misleading to describe them as having high operational interfleet operations though right?

KM- Yes.

RH- It’s still another example of Potemkin projection. As you said in principle, the potential creation of the standing task force for out-o- area operations has great merit. But unsurprisingly it appears that Russia is far removed from this capability. What has contributed to this impotent initiative?

KM- The permanent out-of-area squadrons are great for political purposes including propaganda meant for the Russian people, not the whole world. Naval presence as they had exercised it in the 1960s and 1970s in the Mediterranean was again to become a tool for strengthening political influence, especially in an unstable region as the Middle East after the Arab Spring. That’s why they chose the first permanent squadron to be set up in the Mediterranean. In theory the combat capabilities don’t matter there. It does not matter if three or four or five destroyers are there or just one. The problem for the whole permanent squadron concept is that they have no sea basing concept. They need access to shore facilities and they lack, of course, the required number of ships.

RH- As you said earlier, correct me if I’m wrong, but the only permanent base that Russia has access to is in Tartus, Syria, which is essentially a vassal state now of the Kremlin. In principle Vietnam has agreed, but there are other states who are hesitant about providing permanent presence for the Russian Navy. Do you have any commentary to add to this?

KM- Vietnam is the strongest candidate and they have no problems with the Russians replenishing in Cam Ranh Bay. Only they are not interested in the sharing of sovereignty, which the Russians want. They want their own part of the port where they have full control. All permanent squadrons would need some logistical support in the region where they are to operate, so they have been courting Vietnam. They talked to Cuba, they talked to equatorial Guinea, they talked to Mozambique, they talked to Yemen, even contemplated setting out on a port on the island of Socotra. They are even looking now, in my opinion, at a possible Syrian post asset option. They even courted Cyprus which said “no, no we don’t like it.” Currently in recent weeks they focused on Libya, in Benghazi or Tobruk, and are courting the east Libyan renegade government of Field Marshal Haftar.

RH- Obviously their mediation with the potential government in Haftar reinforces their delinquent activity in the political process about assuming peace. As you said I think it’s most likely that that might be the second best option after Tartus if Assad is able to hold on.

KM- When the Kuznetsov had ended its deployment to Syria, it even made a short stop off Tobruk to welcome Haftar on board.

RH- If I remember correctly I think he had a video link with Defense Minister Shoigu. Getting back to the countries they have been courting, it’s not exactly the most attractive list of modernized and well-funded countries.

Back in the post Georgia conflict in 2008, obviously with their intervention they now occupy 20 percent of the territory, especially in Abkhazia and the port of Sokhumi, do you have any commentary to add to that rapprochement that was officially terminated?

KM- Yes it was officially terminated, but the problem was there were not real sanctions. We said we will not exercise with you anymore and military cooperation programs were terminated. But after two or three years relations were slowly returning to normal, when Putin came to power again. After that lack of Western response to the Georgian crisis, Putin probably thought that he could get away with Crimea. He just had to overcome a 2-3 year lean period and everything would slowly return to normal. He would have Crimea and would have won.

RH- It was definitely a dangerous precedent set by the international community not responding more forcefully to the centrally annexed territory of Georgia. As we established now, financial resources are scarce in Russia, they lack competency to manage shipbuilding, and there is rampant misuse of the budget. What would you say is the current state of affairs and progress of the 2020 state-sponsored shipbuilding program?

KM- The current state is in dire straits. They lack money, they have sanctions in place, the shipbuilding industry is down, subcontractors are not working anymore. While everyone is focused on non delivery of Ukrainian gas turbines, there are many other items lacking. It goes from air conditioning, convenience items, diesel engines, they got German engines from German MTU, now they are looking for China which has been building MTU engines under a license agreement. But those engines are 1980s technological standard so nobody cares whether they get them or not.

RH- Hardly a powerhouse on the sea if they are searching for 1980s engines…

KM- Yeah. Subcontractors cannot deliver systems, but that is not sanctioned necessarily. Just recently there was a report that the commissioning of two modern frigates has been delayed because a subcontractor cannot deliver the Russian-made air defense systems for them. They lack skilled workers. The shipyard infrastructure is degrading. There is confused planning. They use overly confident data brought in to save money or to get contracts, and then afterwards have to say “we calculated all wrong” which leads to more delays. They have corrupt and incompetent bosses, managers. And the Russian Ministry is very reluctant or not at all paying for military contracts. They have no quality controls. Just today there was news that Vympel shipyard has to pay fines for delivering faulty diesel engines for interceptor craft. Once in St. Petersburg one of the most renowned shipyards had to fire its director for inability to complete 3 arctic support ships. And completing them in the other shipyard, Kaliningrad, where the situation is not much better by the way. On the other hand. The Admiralty shipyard in St Petersburg delivered all six Kilo Submarines to Vietnam on time. One reason was most probably they had been paid on time.

RH- One sliver of hope most likely in the native shipyard industry, as we said the shipyards are incapable of producing indigenous replacements that substitute for sanctions post Crimea. Despite the apparent amicability between President Trump and President Putin, it looks as if the honeymoon is over. What could they take away in terms of the shipyard industry with this relationship?

KM- They used to announce great achievements, saying that in 2017 we will have new gas turbines to build into our new frigates, but only very few indigenous systems have made it to serious production. There are year-long delays, the gas turbines announced for this year are more likely to be available in 2019. And the problem is not only to replace sanctioned goods, but lack of quality with their very own weapons systems.

RH- Klaus, the sum total of your analysis paints an ugly picture moving forward for the Russian Navy. Despite this, you stated in the book that the Navy can expect greater autonomy, flexibility with higher sea endurance, and better sustainability with out -of-area operations. Based on the given strengths, financial resources, and less-than capable industrial complex, what is the likelihood that this will be achieved?

KM- I do not see them out of the doldrums anytime soon. To the contrary, in my opinion, economic shortfalls will continue to limit defense spending and delay nearly all shipbuilding projects. Just have a look at the oil prices. They are much too dependent on oil exports and natural resource exports and energy exports. The prices are much below what they need to sustain their economy. Just recently they announced slashing the fiscal year defense budget by 25 percent compared with 2016. Certainly this is not driven by a goodwill signal for arms reduction, but by economic shortfalls. We will continue to see several year delays to nearly all shipbuilding programs, at least complex major combat ships. They will roll out small port/harbor tugs and small boats. Publicly, meaning to their own people, they will claim huge successes. In reality they will basically stay where they are.

For the Russian Navy that means that they will stay in the marginal seas, they will be defending the motherland, and that will remain the main mission. There will be out-of-area operations, but merely in the form of cruises, no power projection from the sea. Programs do not perceive a major seabasing capability, which is required for projecting power from the sea.

RH- Well Klaus, based on our working hypothesis about if the Russian Navy was either a Potemkin or power projection, it seems quite evident that it is more Potemkin than anything. If you were advising Russian President Putin, what priorities would you set, and the final operational takeaway for assessing the Russian Navy with great power aspirations?

KM- If I were Putin, I would for the Navy focus on homeland defense and marginal seas. I would stop bullying neighbors, which can only lead to an arms race that Russia has no chance to win. I would try to mend broken ties. The instruments for dialogue with NATO are still in place, and in some fields, far from public view, Russia is even talking to NATO nations. Just yesterday, in Boston in the U.S., the Arctic Coast Guard Forum which includes Canada, Finland, Greenland, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the U.S. signed a doctrine of tactics and information sharing for operations in arctic waters. So Russia is signing a document, a protocol for combined operations with NATO nations. That is worthwhile remembering. Putin, and we all should realize that Russia is a political superpower with its role in the the UN Security Council, militarily is a regional power, spanning several regions from the Pacific to the Atlantic and to the south. It is made a global power only by nukes. Except for maybe shows of force with global deployments, you will not see any power projection from the sea by Russia.

RH- Just to clarify for readers and listeners regarding the recent contract signed with arctic powers, both Finland or Sweden aren’t NATO members. Klaus, again, undoubtedly the current Russian statecraft shows no sign of being diminished. it is critical to never overlook their Potemkin posture on the high seas. There’s a litany of facts mentioned that range from a lack of competencies, insufficient funds, and incompetent management just to name a few. Captain Mommsen, thanks again for providing such a timely description on the Russian Navy. If you want to follow up on this podcast or other pressing maritime issues, you can find the Routledge Handbook of Naval Strategy and Security online, and most importantly don’t forget to check out the official Kiel Seapower website for all the latest updates on marine security issues. As usual, listeners, I will be back shortly to discuss more maritime issues. From the Institute for Security Policy at the University of Kiel, I’m Roger Hilton saying moin moin and farewell. Thanks everybody.

Klaus Mommsen was born in 1948. In 1968, he joined the German Navy where after graduating he became a naval aviator. In 1982, he attended the Canadian Forces Command and Staff College. His subsequent career saw him mostly employed with military (both naval and joint) intelligence. In 2002, he retired as Captain (Navy) from his last posting as Deputy Chief of Staff (Intelligence) of the German Fleet. As early as 1992, Mommsen started writing for the German naval magazine MarineForum (which until today lists him as editor foreign navies) and since has become a renowned German columnist for international naval affairs. He is married and lives in Germany, near Bonn.

Roger Hilton is a nonresident academic fellow for the Institute for Security Policy at the University of Kiel.