Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Dustin League and Dan Justice

“Motor vessel Pangjang, you are entering a United States-designated exclusion zone. Due to the current state of war between the People’s Republic of China (PRC), immediately secure your engines and await further instructions. In accordance with *static* you will be directed to proceed to a nearby inspection and control point. If you deviate from these instructions, your vessel will be stopped with appropriate force.”

The master of the Chinese owned-and-operated bulk carrier Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng shook his head in disgust, only some of which was due to the American bastardization of his ship’s name. On the outbreak of war, the U.S. had designated the whole of the South China Sea along with the entire Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos as exclusion zones, ordering all merchant traffic to comply with strict traffic lanes and subjecting all vessels to inspections as part of their effort to blockade the People’s Republic into submission. Even long-time allies of the U.S. had voiced concerns over the scope of the U.S. restrictions, and protests had been logged not only by the PRC but by several affected ASEAN nations.

The PRC protest had largely been a pro forma move even as they recognized the toothless nature of the orders. The U.S. Navy, even with the support of local allies, lacked the capacity to simultaneously combat the People’s Liberation Army and Navy’s consolidation of rogue Taipei and patrol their exclusion zone. Even maintaining sufficient forces near chokepoints such as Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok Straits represented an unaffordable strain on USN forces. The Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng, like all of the carriers whose cargoes the PRC had designated as national resources, had been provided with daily status reports by the government on the status of enemy forces in the area and that, confirmed by his own shipboard radar, showed no Americans or their allied warships within hundreds of miles. Their Coast Guard had established an inspection station roughly halfway between Sunda and Lombok Straits off the south coast of East Java. It was undermanned and overloaded with compliant shipping. Some of the PRC’s own vessels, those with less strategically important cargos, had even been directed to the station in order to provide reports on its operations. In addition to U.S. and allied Coast Guard vessels, there was apparently a sizeable contingent of U.S. Marines conducting visit and inspections.

Militarily, the ship’s master had more limited information. He knew that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) operations around Taipei were proceeding successfully despite America’s futile attempts to roll them back. The U.S. carriers were being held at bay and kept beyond their ability to strike by the Second Artillery, and the PLAN surface fleet had established a secure perimeter around the island. Supposedly, the U.S. had established missile batteries on the northern tip of the Philippines, but they lacked the range needed to hit the fleet. Purportedly the U.S. submarine force remained a significant threat, but the ship’s master had no information on their operations. Neither the PRC nor the Americans were revealing any details on lost submarines, so it was impossible for him to gauge which side held the advantage in the undersea war. When the ship’s master had been notified that his vessel was now considered a critical national asset and subject to the military command to run the U.S. blockade, he’d been assured that the U.S. submarines would not bother wasting a torpedo on his vessels. They would need to save their inventory for PLAN vessels which, he had also been assured, could protect themselves.

There had been news of American amphibious forces trying to hop across the south Pacific on small, empty coral islands like they had done eighty years ago, but no warships. Even the challenge had been sent not by a USN warship or Coast Guard vessel but from a large unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) circling high above. The master also had reports on those UAVs, they were long-endurance reconnaissance types with no organic armaments. Another empty threat. Once he passed through the Lombok Strait and into the South China Sea, the risks he took in running the U.S. blockade would increase, but he would also be entering into the PRC’s own backyard where they could provide direct protection.

“Maintain course and speed,” He ordered. “Ignore all further hails.” His bridge crew acknowledged his order with calm, quiet professionalism. If any of them disagreed with the assessment of the situation as he’d briefed that morning, none showed their concerns. The drone circling overhead continued to pace them, repeating its message, its demands growing increasingly terse and harsh. The ship’s master counted no less than three times his vessel was threatened with lethal force with never a blip on the radar to indicate a closing vessel or aircraft. Open seas, open skies, and toothless demands.

Twenty-five minutes after the initial challenge, two long-range anti-ship missiles, their telemetry continually updated by the overhead drone, slammed into the Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng. One hit amidships just above the waterline, its warhead punching through the hull to let the ocean flood in. The second, less than a second later, struck the superstructure, taking out the entire bridge. The missile hits were insufficient to sink a vessel as large as the Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng, but they were more than capable enough to leave it a helpless derelict. Mission kill.

*****************************************************

First Lieutenant Tommy Hart, Commanding Officer of Charlie Platoon, 1st Battalion 3rd Marines, reviewed the video footage, noting the impact points and subsequent motion of the vessel. Smoke billowed thick and black in a column that rose as high as the UAV’s own operating altitude before being thinned by the wind. Finally satisfied, he logged the first kill of his maritime interdiction platoon.

“Flash , Flash, Flash, Alpha Sierra, Alpha Mike, this is Hotel Charlie Six,” Hart said into the radio, calling both the Surface Warfare Commander and the Amphibious Element Coordinator at the same time, “Splash, Skunk Two, with Bruiser, Over.” The acknowledgment came back. He couldn’t be sure, but he thought it was the first such kill of the war and he felt pride in his team. And maybe just a twinge of instinctual moral qualm. He’d joined the Marines to defend his nation and he’d fully expected that would mean killing the enemy during times of war; but when he’d joined Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps he hadn’t thought of unarmed oil tankers as “the enemy.”

He noted the position of the tanker – fifty miles south of Lombok Strait and eighty miles from his own position on East Java. Well inside the range of the anti-ship missiles on his High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) but close to the edge of his targeting UAV’s range. The range from the strait was critical. Hart wasn’t privy to the governmental horse-trading that had to be going on behind the scenes, but he knew that Indonesia had demanded strong assurances before allowing the Marines to deploy their chokepoint control stand-in forces on their territory; chief among those was the requirement that no vessels be sunk within twelve nautical miles of any of the straits’ entrances.

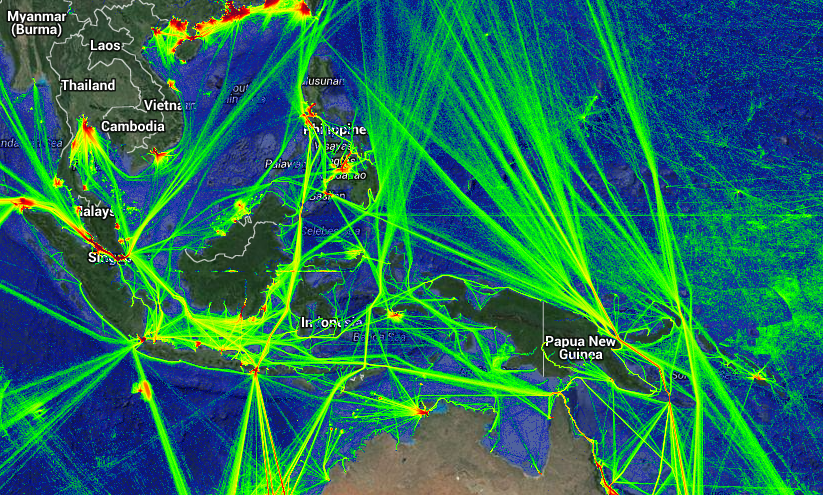

Against almost any kind of PLAN warship the strike would have been impossible. First there would have been the difficulty in finding a target – warships maneuvered too often, too fast, and refused to follow predictable transit paths – which would have exhausted his small UAVs’ endurance. Then there was the problem of PLAN anti-air defenses. Even with the new missiles, the HIMARS’ ability to generate a large enough salvo to overwhelm a modern frigate or destroyer’s defense was woefully insufficient. But merchant vessels and oil tankers were another matter. Those he knew where to find – if they wanted to deliver to resources the PRC so desperately needed, they would have to come through Lombok Strait or one of the other chokepoints in the archipelagos surrounding the South and East China Seas. Lombok was the responsibility of his company, the others were guarded by similar U.S. Marine Corps units. Small stand-in forces, rapidly deployed around the First Island Chain, teamed with unmanned systems for patrolling the adversary’s sea lines of communication, finding and challenging their shipping, and finally targeting them for the HIMARS’ missiles.

“Nice flying, Torres,” he said to the young Marine who’d been piloting the UAV. Torres has been near the top of her class at Fort Huachuca and could always seem to squeeze an extra 30 or 60 minutes out of the UAV’s batteries. Endurance wasn’t a big factor now, the drone had only been up six hours. Seventh fleet had sent them the Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng track earlier that morning from a Triton that was up, allowing Hart to plan his UAV time well. In a combat zone as large as the Pacific, even the remarkable range and endurance of Hart’s tactical UAVs was insufficient to large-area search problems. The coordination of assets and passing of track data through the Global Combat Support System – Navy Marine Corps was critical to the platoon’s mission.

“Push their updated position, course, and speed to Geeks so the Coasties can send someone out to haul her to port.”

“All right everyone, time to move,” he ordered the rest of the platoon. “Handoff to Baker Platoon in fifteen.” They were outside the PRC’s anti-access/area-denial zone of control, but there was still enough risk in detection that no one wanted to wait around for a retaliatory PLAN strike. His platoon was already making preparations to step off. The HIMARS crew were completing final post-firing checks and battening down for departure. His entire platoon consisted of four elements; two semi-truck sized HIMARS batteries, a UAV carrier roughly the same size that could carry four of the long-range drones; a counter-precision guided munition point defense battery; and a small transport. A lot of firepower for a first lieutenant, though he’d feel unarmed until he could get the HIMARS batteries re-loaded from one of the company’s caches.

They had only been on Lombok for a week, dropped off from the Essex, their gear and the HIMARS truck brought ashore by some of the “Mike Boats” the Marines had started picking out of the various boneyards across the country. Already Hart was starting to fantasize about a shower and a burger when they would be picked back up after another 10 to 12 days. Or would there be enough shooting that they’d go Winchester early? He shook those thoughts from his head and returned his attention to the pack out. They would be packed up and on the road within thirty minutes. Until he could reposition and redeploy his force, this sector of the U.S. exclusion zone would be the responsibility of Baker Platoon who, he knew, was roughly fifty miles west of his position, on the other side of Lombok Strait itself.

Within hours, Hart knew, the crippling of the Píng Jìng De Hǎi Yáng would be all over the news. The PRC would shout in protest and the U.S. would again assert its ability to enforce exclusion zones during a time of war. The Navy and Marine Corps would explain both the need and the precedent for such operations – one had only to look back to World War II when the Navy had declared unrestricted submarine and air warfare against Japanese commercial traffic. He suspected other PRC vessels would continue trying to run the blockade and there would be a handful of more high-profile sinkings, but he doubted they would last for long. Once it became clear that the Marines could and would effectively target and destroy any uncooperative vessel, there would be very, very few ship masters willing to take the risk.

Hart had not joined the Marine Corps expecting this kind of mission. He’d joined at a time when the USMC had just begun a major re-alignment, shifting from protracted ground operations back to a role supporting naval operations in the littorals. Even then he’d expected to be employing the capabilities of his platoon against adversary naval targets – against warships. But there’d been a need to expand the USMC role beyond naval and into maritime support. The Corps had purchased the weapons and developed the skills needed to combat a great power, but like the submarine force in World War II, they’d found that those same capabilities could be far more effective against an adversary’s commerce. And, like the silent service, what had once been seen as a “lesser included mission” had become a critical role in a major war.

*****************************************************

The vignette described above is an attempt to expand on some of the concepts described in Commandant Berger’s Planning Guidance to the US Marine Corps.[1] The capabilities employed by Lieutenant Hart’ platoon – the HMARS armed with anti-ship missiles, the tactically-controlled long-range UAVs, and the counter-precision guided missile defense – are all explicitly called for in that document. The uses we postulate for them – the destruction of unarmed merchant vessels in defense of a distant blockade – are not. Such use relies on several underlying assumptions about the nature of a future conflict which may or may not be borne out. First that the United States enters into war with another great power. Second, that in such a war the U.S. would again resort to a similar commerce destruction strategy that was a keystone of the Pacific War against Japan. Third, that the U.S. Marine Corps would be tasked with such a role. Fourth, that U.S. allies or neutral nations in the region would allow a force like Hart’s to operate on their territory. Even with the 350 nautical mile missiles and 200 nautical mile drones the Commandant of the Marine Corps has called for, the Marines need somewhere to stand.

Berger has called on the Marines to become an integrated naval force to prioritize operations in the littorals that support the Navy’s Distributed Maritime Operations concept and counter great power rival investments in anti-access/area-denial capabilities. The missions implied in the guidance call for Marine stand-in forces to operate inside contested zones and provide anti-ship and anti-air fires, with the strong implication that the target set will be the enemy’s military assets. Going against the PLAN on their home turf, the Navy should certainly welcome the additional firepower; however, it may not be the best use of the Marines’ new capabilities.

There is no shortage of commentary on the tyranny of distance the USN would face if it finds itself in a shooting war with China. It bears repeating again. Assuming an invasion of Taiwan as the source of conflict, and PLAN deployments converge around the island nation, there is precious little real estate for the USMC to place its stand-in forces and still have the range to hit their targets. Additionally, simply getting missiles in range will be of little use if they cannot penetrate the target defenses. The PLAN has capable warships with modern anti-air defenses that will require extremely capable missiles fired in large salvos to defeat. How many HIMARS batteries will be needed to achieve a mission kill on even a single PLAN destroyer, let alone a surface action group with coordinated defenses?

The U.S. Navy went through a similar experience in the lead up to World War II. The submarine community had spent the interwar years developing a fleet of boats to combat the Imperial Japanese Navy, softening it up before the expected battle line confrontation by attriting IJN warships. Instead, those boats which had been built to sink battleships spent much of the war sinking Japanese merchant vessels, choking Japan’s critical supply lines. What had been seen as, at best, a lesser included mission, became the defining task of the community.

Joel Ira Holwitt’s Execute Against Japan[2] details the evolution of U.S. Naval thought and policy on unrestricted warfare. It chronicles the long process of legal, ethical, and strategic issues the Navy had to work through before executing the doctrine. The analogy is not perfect of course. China is not an island, dependent on outside resources to the same extent as was Japan. However, this line of thinking is still valid, and it is important to consider if what we might need to do wasn’t already planned for. Similarly, the Marine Corps should be exploring the larger mission set inherent in maritime operations. That may involve commerce destruction in support of blockade operations and chokepoint control. It may involve seizure of China’s “string of pearl” bases around the globe. As the Marines conduct the extensive wargaming and analysis Gen. Berger also calls for, they should look beyond the inherently military target set in a specific region and embrace the potential for action across the larger maritime domain.

The commandant is committed to designing a Marine Corps which will remain the “Force of Choice.” He has outlined the salient features he believes that force will require, the challenges it will face, and the path to getting it built. While General Berger’s assessment, goals, and methods are welcomed, a broader vision for the naval services is needed, one which harnesses their capabilities across the whole range of maritime security.

Dustin League is a Senior Military Operations Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and a former U.S. Navy Submarine Warfare Officer. The views and opinions expressed here are his own and do not reflect those of SPA, Inc.

LCDR Dan Justice is a U.S. Navy Foreign Affairs Officer and former Submarine Warfare Officer. The views and opinions expressed here are his own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy.

References

1. Berger, G. D. (2019, July 17). Commandant’s Planning Guidance. Retrieved from Marine Corps Electronic LIbrary: https://www.marines.mil/News/Publications/MCPEL/Electronic-Library-Display/Article/1907265/38th-commandants-planning-guidance-cpg/

2. Holwitt, J. I. (2009). Execute Against Japan: The U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Featured Image: “S-300V” by Mikhail Selevonik via Artstation