1980s Maritime Strategy Series

By Dmitry Filipoff

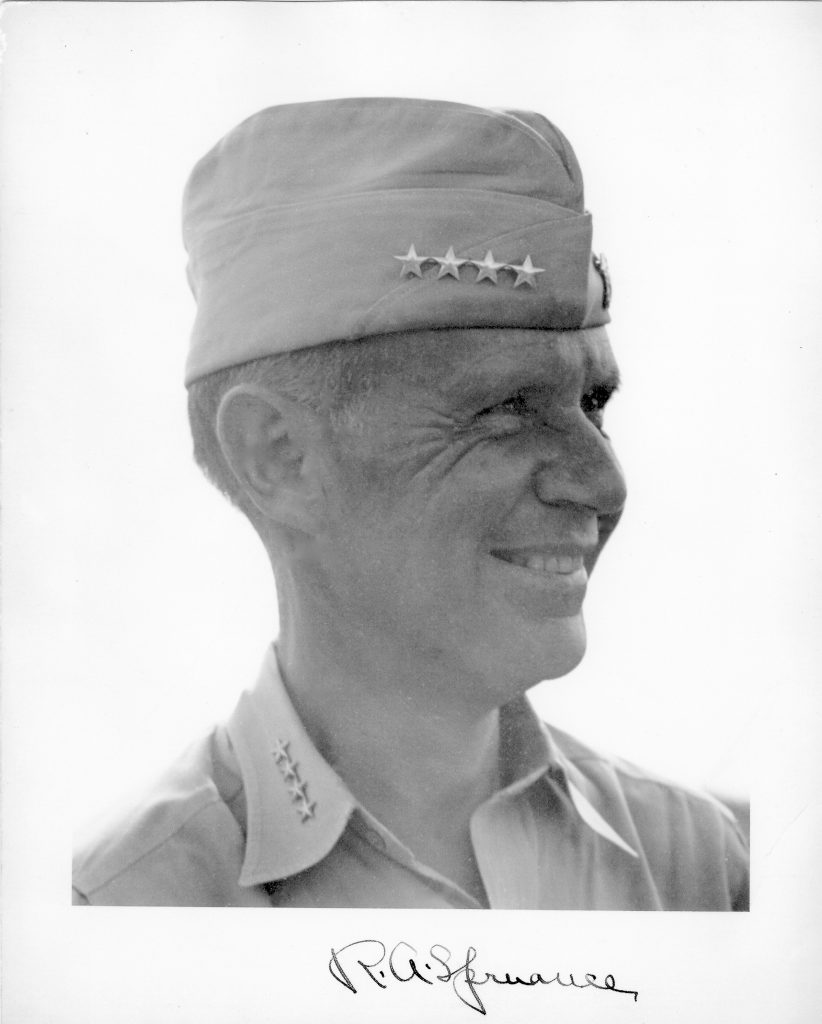

CIMSEC discussed the 1980s Maritime Strategy with Captain Pat Roll (ret.), who served as a staff tactician for Admirals Ace Lyons, Joe Metcalf, and Hank Mustin. In this conversation, Capt. Roll discusses how tactical development fleshed out the execution of the Maritime Strategy at sea, the Navy’s use of cover and deception operations to move battle groups undetected, and the core relationship between strategy and tactics.

In what sort of roles did you contribute to the tactics undergirding the Maritime Strategy?

My work on the Maritime Strategy started when I met first Ace Lyons in the 1970s, who was at the time the chief of staff of Commander Carrier Group 4 staff, embarked on America. I was a fresh-caught lieutenant commander and I had just graduated from the Tactical Action Officer school. I came aboard the staff as the staff tactician. My background was electronic warfare, that was my subspeciality. Included there was of course cover and deception. So I came aboard the staff as the tactician and he came as a warfighter and that’s what he did, he put together a small cadre of folks when he was Captain James “Ace” Lyons, and I was one of his people.

And then we sort of split to the four winds and he was promoted to rear admiral and sent to the Pacific. The years passed, and then in 1981 when John Lehman became Secretary of the Navy (he and Admiral Lyons were friends), he asked Admiral Lyons if he wanted to take 2nd Fleet. At that time Lyons was in OP-06 in the Pentagon. He then took 2nd Fleet in the summer of 1981.

At the time I was the combat systems officer on the new construction USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70). So he called me to the flagship Mt. Whitney and he said, “I want you to sail with me on an exercise (Ocean Venture) we are going to have here shortly, and bring some modern tactics with you.” I was a commander at the time. I said, “Yes, sir, but I really am gainfully employed, I’m putting together the combat center for Carl Vinson.” And he said, “Well I’m sure you can find somebody to cover for you.” Well, whatever you say, Admiral. And so I sailed.

We were gone for three weeks in the North Atlantic, and it was just a regular 2nd Fleet exercise at the time. After the exercise he said to me, “I want you on the staff. I want you to be the tactician.” And I said, “Okay, I’ll do it, just let me finish up the work on Carl Vinson.” Which I did. And then the winter of 1981-1982 after contractor sea trials for Carl Vinson I was released to work for Ace Lyons.

At the time the component commanders of the 2nd Fleet, all of the CARGRUs and the DESGRUs, they all had their own TACMEMOs, tactical memoranda, tactical notes, air wings especially, on how to employ the F-14, A-6, and the EA-6B Prowler, and how to do it effectively. All these different tactical notes were floating around, but they were platform-specific, disjointed, and not always written with the same language.

So he got a couple of us together and said, “Look, we’ve got to make rhyme and reason out of all this paper that’s out there. And train in its accordance with what’s required of the Maritime Strategy.” We took a careful look at what came out of the Pentagon and thought we had a lot of material here that could be distilled into a publication that would outline how to fight the 2nd Fleet. More importantly, how to fight the Striking Fleet Atlantic.

These were the Fighting Instructions.

That’s exactly right. So we started working with the CARGRUs and the DESGRUs to assemble these tacnotes and tactical memoranda, make rhyme or reason out of these things, and put it into a publication with common language. And with applicability to all platforms, not just platform-specific, although some of them were of course.

So we put it all together and sent it to the Center for Naval Analyses. Phil DePoy was the director at the time and he gave it to his people and they blessed it. They sent it back, said it looks good, and we published it. And it became a war-at-sea sourcebook for all component commands within the Striking Fleet.

How was it implemented, how was it used?

It was distributed as a directive. It was almost like a 2nd Fleet instruction: you will digest this, and you will incorporate electronic warfare and cover and deception into your tactical planning. And all tactical plans will be submitted to the commander of the 2nd Fleet, commander of the Striking Fleet Atlantic, for approval.

There is another component here: Anti-Submarine Warfare Group 2. That’s a British command, it was Rear Admiral Derek Reffell. He put together the outline for force disposition, it was a large grid, and he started work on decentralized command and control, which would allow for a large force to deploy to the GIUK gap and into the Norwegian Sea.

So we began to train for deployment with the anti-submarine warfare group, with the NATO vessels, although to be honest, it was 2nd Fleet that was driving the train, not the Striking Fleet. We did a successful exercise called Ocean Venture. Which was, in fact, executing the Maritime Strategy. And we went into the Norwegian Sea in the summer of 1982 on Northern Wedding. John Lehman’s book Oceans Ventured outlines what happened. They were successful exercises.

What we learned was that it was very difficult. The intent was to transpose the Norwegian Sea from a Soviet lake into a 2nd Fleet stomping ground. But what we found was it was impossible to stay away from the TU-95 Bear. The reconnaissance planes. They were all over us. We also learned that the Norwegian Sea is not friendly toward surface warfare, not by a longshot.

Later on I was Admiral Lyons’ tactician when he was CINCPACFLT and he asked me to join him as flag secretary, but in fact I was a tactician. His first move was to get the 3rd Fleet to sea, to become a warfighting entity, and operate in a similar mold that he had made the 2nd Fleet into. When Ace Lyons had taken over the 2nd Fleet, it had been a training command preparing ships and staff for deployment to the 6th Fleet. He had changed all that, saying this isn’t a training command, it is a fighting force. And he had made it into a fighting force. Sure, a lot of guys had to fall by the wayside for that, but that’s just how that happens.

When Ace came out to the Pacific, the first thing he did was get Vice Admiral Ken Moranville to move his 3rd Fleet from Ford Island to a flagship and then become a fighting force. Ace made cover and deception a household word in PACFLT. He gathered all the CARGRUs and DESGRUs from all over the Pacific, brought them into Pearl Harbor, and gave them marching orders. He said, “We are not going to be spread out here and there just maintaining presence. We’re going to fight the Maritime Strategy in the Pacific.” That was oriented on the Kuril Islands. He would run mirror exercises like we were going to take the Kuril wedge, to include amphibious forces, and then at the last minute would turn away. It was stressing the Soviets out.

Previously when Ace Lyons had finished up his tour at 2nd Fleet, Vice Admiral Joe Metcalf took over. Metcalf took a look at the readiness index and he liked it. But he was really antsy on command and control, and he was right. We didn’t have digital communication yet, we were still in the analog world. HF was not reliable. And we didn’t have the satellites that we have today. So we had to rely on decentralized command and control, which was where the Fighting Instructions came in.

The Fighting Instructions were instructions on how to operate, and of course they were dynamic, they were not chiseled in stone. But the Fighting Instructions allowed for support of operations for ASW and AAW, which was where our concern really was. So we were in the Norwegian Sea and we fleshed all the difficulties out, including command and control.

Admiral Metcalf was there for a little less than two years. Then Hank Mustin came in. And Hank Mustin came in like a tidal wave.

Of all the admirals I have worked for, if we were going to go to war, we needed Hank Mustin. As the custodian of the Fighting Instructions and the staff tactician, I got close to Mustin. We played racquetball every morning before work at the piers on Norfolk. I got to know him pretty well.

He took the Fighting Instructions to a new level. For him they became the bible. And they were already dynamic, but what he did (which none of the other guys did) was establish the Tactics Board. It was very clear that he wanted anybody who was not deployed to travel to Norfolk once a month, sit down, and take a careful look at how to implement the Maritime Strategy tactically.

I was the recording secretary of the Tactics Board. After these monthly meetings, after the decisions, points of discussion, and the hard spots were worked through, I made sure these got on paper. I authenticated and Hank Mustin signed. We were pretty confident we could execute whatever task was given in the name of the Maritime Strategy in the north Atlantic.

Because we were so concerned with the TU-95 reconnaissance planes, we thought to ourselves, what if we operated in the fjords? What if we took a carrier group into the Saltfjorden fjord out of Bodø, Norway, or the fjords by the North Cape before you go into the Barents Sea. We operated in pretty good water, but not a lot of sea room.

RDML Paul Ilg went into the fjords and did a really in-depth study, especially into the Saltfjorden fjord, on how effective flight operations could be, and at the same time, remain concealed from the TU-95s, which would have to be right on top of you to see you. We were really attracted to operating out of the fjords and the plan was to get into the fjord with a full complement of an air wing, and you could then conduct strikes across the Baltic into Kaliningrad, Leningrad, and some of their big shipyards. The only downsides that Paul Ilg came back with was sea room and weather. Weather was a constraint, it was always a consideration.

Our reconnaissance flown out of Rota, Spain kept a pretty good tab on what the Soviet Navy was doing in those shipyards, their exercises, and testing and development. We had great intelligence support.

Hank Mustin was faced with fuel constraints. He didn’t have a lot of bucks for fuel. So he established what he called the Battle Force In-Port Training (BFIT). We would run these exercises in Charleston, in Norfolk, Mayport, and King’s Bay, and run these Maritime Strategy-oriented exercises without anybody leaving port. It was a thing of beauty. And everybody not deployed would get trained up on aspects of the Maritime Strategy and not use any fuel. The readiness dividends were incredible. These boats would button up like they’re getting underway and they would carry out the tasks assigned.

If I was to identify the most important contribution to fleet readiness that I’d seen, it would be the Battle Force In-Port Training exercises. We loved it. It was Hank’s brainchild.

The communities each had their own sets of tactics but didn’t often interact with one another. How did you bring them together and make sure they were on the same sheet of music and socialize these tactical concepts?

The communication between the fleet commander and the subordinate DESGRUs and CARGRUs was excellent then, it was really dynamic. Every subordinate knew what Hank was thinking. He made the statement, “If you take the first hit, and you survive, I will fire you.” Everybody understood that.

So with that kind of emphasis and that kind of urgency, everybody had their ears up and their lights on. Before each exercise, he would gather everybody aboard Mt. Whitney and they would plan the exercise together. After the whole thing was over there would be a hot washup, maybe a day or two, and all the weaknesses and nuances would be fleshed out and addressed. Those kinds of working relationships between the communities were there. No independent steaming, no independent operations, it was cohesive and focused on whatever aspect the Maritime Strategy demanded.

How would you describe the difference between strategy and tactics, and how do they relate to one another?

Simply stated, strategy is force employment structured to accomplish a theater-level mission or portion thereof considering enemy composition, geographic location, logistics, force availability, etc. Strategic planning and execution usually resides within the battle force staff in collaboration with the theater commander. Tactics in its basic form is centered on fighting the ship or air wing. More to the point, tactics is fighting the ship/air wing as part of the battle group warfighting doctrine in support of an assigned task.

Without a strategy, putting together tactics is like the sound of one hand clapping. Unless you have a strategy in place as to what it is you want to do, unless you understand that, then all the effort in the world may or may not accomplish what you want to do. You have to have a strategy, you have to have a concept. If you don’t have a strategy, how can you put together fleet tactics to support something that doesn’t exist?

Three times a year we would take Mt. Whitney up to the Naval War College and we would run those modules and exercises. We would have a red cell, and we would have all the other ships, and we would run these exercises at Sims Hall. I was on loan to the red cell because they sometimes didn’t have tactically-oriented people to run the enemy, so that’s what I did. We’d finish up these exercises and everybody would learn. Everybody understood what was required.

Electronic warfare wasn’t appreciated originally, if you could speak more to that.

Electronic warfare was never attractive. It didn’t explode, it wasn’t a rocket, you didn’t sink ships. It was a higher level of warfare that was more of a force multiplier than a lethal weapon. Because of that the Navy never really invested heavily in electronic warfare. It was a mindset.

But you had guys like Ace Lyons and Hank Mustin, and they think well wait a minute, for minimal expense I can double my force. I can move my battle group without the Soviets knowing it. And we did it.

For example, it didn’t take long in 1986 to determine that the Persian Gulf was awash with Soviet mines and that the Kuwaitis were losing tankers. The State Department said we needed escorts for our tankers to move out into the Arabian Sea without running into mines. The word went out that they really needed help. CJCS Admiral Crowe told CINCPACFLT Admiral Lyons they needed minesweeping capability in the Gulf. So we moved a battle group to the Arabian Sea from the middle of the Indian Ocean in Diego Garcia without anybody knowing about it. It was the swiftest, coolest thing we’d ever done. We played the satellite game, we did total radio silence, and with high speed. That was cover and deception at its best. And that is a tactic, not a strategy.

There’s another thing to consider: logistics. It takes two weeks for a unit to go from San Diego to Hawaii. And then it takes another two weeks to go from Hawaii to the South China Sea or East China Sea. I didn’t realize this until I got out to the Pacific, but I didn’t really have an appreciation for distance. Maintaining the logistics to keep a ship out at sea with at least 70-80 percent of its fuel and other necessities, that’s a challenge. Logistics are always the big concern. All you have to do is read any of those historians that did the Pacific War and see what they had to say about support, the incredible amount of support that is needed to keep a force of several battle groups operating at sea for an extended period of time.

I was the CO of the Fleet Deception Group in Norfolk for three years. We had a lot of electronic warfare players that would support the 2nd Fleet. We would disguise ships, such as take a destroyer and make it look like an oiler, or take a cruiser and make it look like a carrier, things like that.

Sometimes folks don’t like having their sensors and comms jammed in combat exercises. How did they respond to that?

We would put these vans aboard that would simulate the communications you would expect out of a battle group, but it was on just a destroyer, and the CO would have to put up with that. Some received it well. The warfighters certainly did, but not everyone at sea is a warfighter. Not everybody in the War College is a warfighter. And a lot of them, the guys at the CARGRUs and the DESGRUs, a lot of them are administrative types. They didn’t know any more about naval warfare than they did about growing tomatoes. It was disappointing.

But Hank Mustin still took them aboard. And he would say, “You will fight. And if you take the first hit and survive, I’ll fire you.”

Captain Pat Roll (ret.) served for 31 years in the Navy. Specializing in fleet tactics and electronic warfare, he served in a variety of EW assignments, including as Commanding Officer, Fleet Deception Group Atlantic. While attached to Commander, Second Fleet, he was responsible for compiling, editing, and publishing the Second Fleet Fighting Instructions. He served as flag secretary and staff tactician to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, Admiral Ace Lyons, and as Assistant Chief of Staff for Battle Force Command and Control to Commander, Second Fleet, Vice Admiral Hank Mustin. Capt. Roll retired in 1993.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at [email protected].

Featured Image: March 19, 1983 – A left side air-to-air view of a Soviet Tu-95 Bear maritime reconnaissance aircraft, top, being escorted by a U.S. Navy F-14 Tomcat aircraft as the Soviet aircraft approaches the Readex 1-83 battle group. (Photo by LT J.G. Thomas Prochilo via the U.S. National Archives)