By Nick Brunetti-Lihach

Prelude

“We have lost the electromagnetic spectrum. That’s a huge deal when you think about fielding advanced systems that can be [countered] by a very, very cheap digital jammer.”—Allen Shaffer, Department of Defense Chief of Research and Engineering, 2014

“Success in past conflicts has relied on information superiority on the field of conflict; this information superiority has been largely dependent on widespread use of modern sensor and communications electronics hardware and software.”—Defense Science Board: 21st Century Operations in a Complex Electromagnetic Environment, 2015

The enemy maneuvered around our networks. On D-Day, their informatized system of fixed and mobile jammers swept the skies and seas with impunity, severing critical re-supply and our kill chain. We had no counter-attack. As lethal and non-lethal projectiles rained down upon us, we were clueless to the fact that we’d set the conditions for failure years earlier. Their invisible bullets penetrated each gap and seam in our command and control. Like we did to the Iraqis in the first Gulf War, the enemy exploited every mistake. Our failure to protect the electromagnetic spectrum and control our signatures cost us tempo and decision speed.

For years we remained vulnerable in the spectrum due to legacy systems and poor training. Despite the well-publicized Strava scandal and Bellingcat MH17 investigation, we neglected fundamental field craft. Undisciplined emissions bred bad habits and steadily exposed critical vulnerabilities. There were pockets of excellence where electronic warfare and communications were integrated from the top down, but they were the exception to the rule.

The Marine Corps is not prepared for a battle of signatures. Despite being smaller and lighter than the Army, the Marines are no less vulnerable to attacks from spectrally aware adversaries. In today’s operating environment, stand-in forces in the littorals are heavily dependent upon information for sensing and cueing weapon systems. Yet soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines take the electromagnetic spectrum for granted. The communication of information presents a signature and increases vulnerability. To preserve the kill chain and increase survivability, Marines must practice spectrum warfare at the lowest tactical level. To achieve information superiority against modern threats, the Marine Corps must update training and education, modernize command and control systems, and re-organize for spectrum warfare.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps charted a bold vision in his Commandant’s Planning Guidance and followed up with renewed focus on modernization with Force Design 2030. The service has identified programs to divest itself of, reorganized units, invested in ship-killing missiles, and reinvigorated naval integration. The service is also creating “purpose-built” stand-in forces to operate in the contact layer. Yet while Force Design calls for “greater resilience in our C4 and ISR systems,” how the service plans to develop spectrum warfare capability is not clear.

There is widespread agreement the U.S. military has lost dominance of the electromagnetic spectrum. In 2015, the Defense Science Board report found that U.S. military command and control systems are “jeopardized by serious deficiencies in U.S. electronic warfare (EW) capabilities.” A 2017 Government Accountability Office report noted systems continue to contain critical vulnerabilities, despite warnings. The Chief of Staff of the Air Force recently characterized his service as “asleep at the wheel” regarding the electromagnetic spectrum.

The Commandant has acknowledged the Marine Corps is “under-invested” in spectrum warfare-related areas, to include signature management and electronic warfare. Yet the loss of spectrum dominance is also due to legacy command and control systems which will not survive in a conflict between peers. Individual units are also not organized for spectrum warfare, and training and education does not adequately prepare for peer-level spectrum competition.

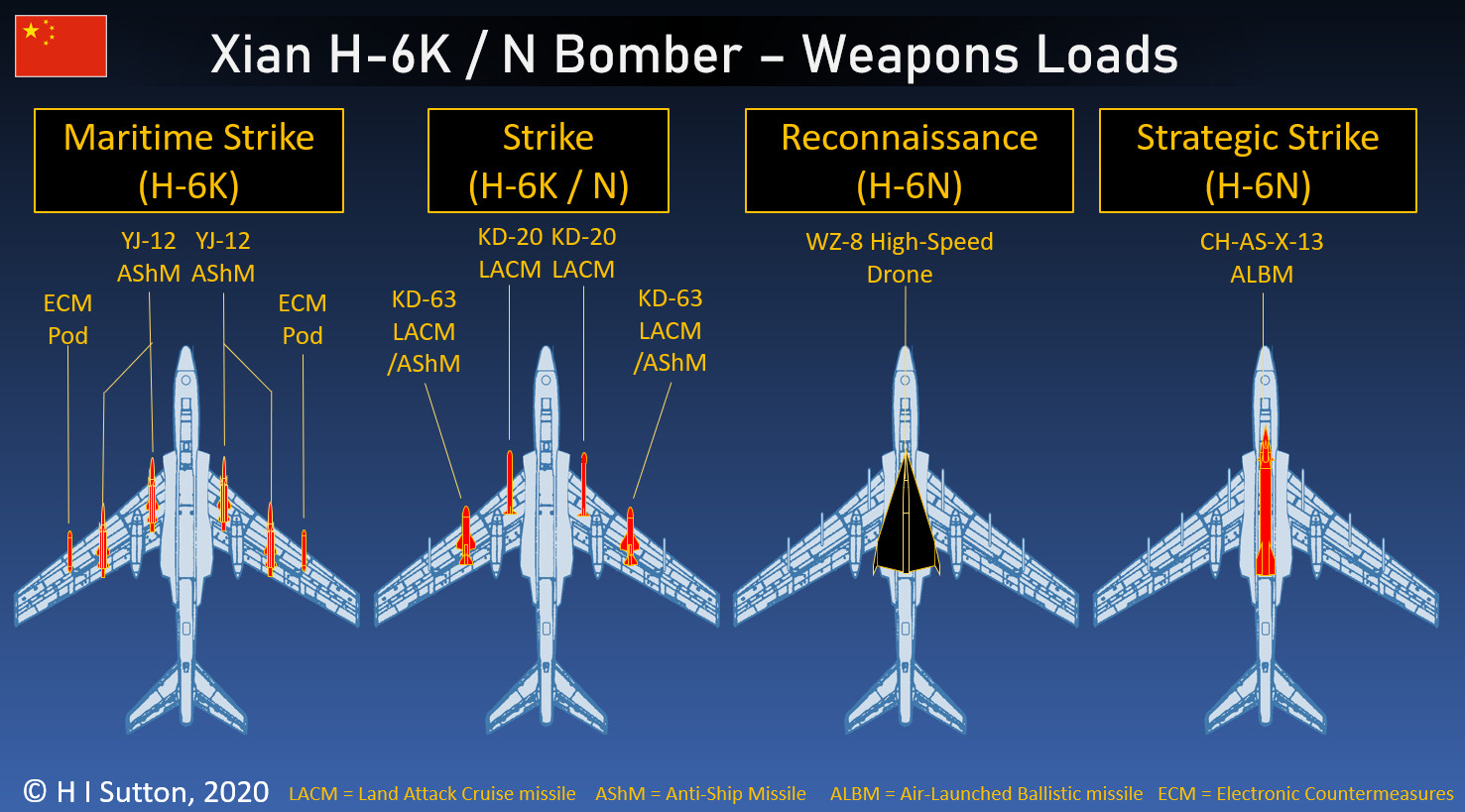

Friendly communications are routinely subject to detection, interception, and exploitation. Threats range from radio direction finding systems, electro-optical and infrared surveillance, and airborne and celestial systems. While military communications are designed with security in mind, the underlying technology in use today by the Marine Corps to secure their radio transmissions (frequency hopping, waveforms) are decades old. Worse, following the Cold War, the Marine Corps cut electronic warfare systems such as the EA-6B Prowler. As a result, electronic warfare capability in the Marines is only a shell of what it once was, and has led the Marines to adopt systems from other services.

Communications and electronic warfare communities are two sides of the same coin. Both rely on the electromagnetic spectrum to provide and protect access to friends, or deny the same to the enemy. But at the tactical level, the Marine Corps does not possess electronic warfare capabilities needed to stress its systems against formidable peer capabilities possessed by Russia and China. At the same time, Marine Corps legacy command and control systems light up the spectrum with emissions.

Marine Corps doctrine outlines a maneuver warfare philosophy to identify surfaces and gaps to avoid or exploit through planning and analysis. Against a peer adversary, the ability to maneuver in the electromagnetic spectrum is a critical capability, while secure communication networks are vital requirements.

Today, planning and coordination between communications and electronic warfare personnel is deficient. Furthermore, within combined arms Marine Air Ground Task Forces, the aviation and ground communities operate different systems to support their networks, detect threats in the spectrum, and manage information. For example, while the Link 16 tactical data network is being touted as a core element of future networks, few communicators have experience or training with the capability. Aviation units have the Light Marine Air Defense Integrated System “drone killer” to detect and jam drones, but ground units do not. As a result, the ground side lacks familiarity with aviation command and control systems, and both lack unity of effort with the electronic warfare community. This results in a wide gap in skill sets, interoperability, and real-time coordination in the electromagnetic spectrum. Given the future links envisioned by the Joint All Domain Command and Control concept, this will better prepare Marines for the spectrum warfare environment.

#1 People: Train and Educate as We Expect to Fight

“People, ideas, and hardware – in that order.”—John Boyd

Materiel and organizational change cannot overcome gaps in training and education. As the Navy is re-learning spectrum warfare, which it calls electromagnetic maneuver warfare, is extraordinarily challenging. Unfamiliarity with the complexities in the electromagnetic spectrum environment is evident when Marines play wargames that envision conditions in a future operating environment. However, there is also a lack of training and education in electronic warfare, and Marines have identified gaps in electronic warfare at the The Basic School.

Pre-deployment training in 29 Palms should not be the first time a Marine is formally introduced to spectrum warfare. The Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept anticipates Marines will operate in a spectrum denied environment under persistent surveillance. Yet as Jonathan George has written, most units still lack electromagnetic spectrum training standards. To address this acknowledged challenge, the Marine Corps should introduce spectrum warfare at entry level schools. Today, other than a small cadre of technical experts, few Marines receive formal training on friendly or enemy radar systems, but are expected to plan or operate in and around active and passive sensors. Most subject matter expertise in spectrum warfare resides far from the battlefield within organizations such as Marine Corps Information Operations Center.

Second, commands can leverage wargames to teach Marines how to think about operating in a spectrum-contested environment. Wargaming is an inexpensive way to train and educate. In recent years, commercial and military wargames have added the dynamics of the spectrum environment, to include communication links and electronic warfare. For example, DARPA has developed a computer-based wargame that uses an array of communications links and jammers to stress a player’s ability to complete an assigned mission. Wargames can supplement exercises and perhaps in some cases more effectively represent the dynamic challenges of the spectrum environment.

Third, the Marine Corps should add a spectrum warfare curriculum to all officer and enlisted career-level schools. Training and education in spectrum disciplines vary across training and education units, along with standardization and properly trained instructors. Baseline curriculum should be developed within the Deputy Commandant for Information community, with input from all relevant communications and electronic warfare disciplines, anchored by observations from recent unit deployment and force-on-force training after-action-reports.

#2 Ideas: Organize Tactical Units for Information Superiority

“Proliferating systems, rapidly procured and fielded, are making for an increasingly crowded spectrum. Our freedom to operate is jeopardized. As our adversaries learn to get the most from their asymmetric strategies and close the gap with us technologically, our edge in combat will increasingly rely on our singular competencies in integration and operational excellence.” –Huber, Carlberg, Gilliard, and Marquet, Joint Forces Quarterly, 2007

Electronic warfare seeks to detect, identify, and exploit enemy signals. Conversely, communicators enable command and control. While both communities are dependent upon the electromagnetic spectrum, they often operate in parallel. In recent years, more voices have argued for greater resources and integration, but only incremental progress has been made at the tactical level.

In today’s dynamic electromagnetic spectrum environment, battalions, squadrons, and regiments must be organized to sense and fight within the spectrum. For example, per Marine Corps doctrine, a Battalion Landing Team is co-located with an Air Support Element to coordinate and de-conflict air support and fires. Yet no such coordination exists at that level for spectrum warfare. Doctrinally, Electronic Warfare Coordination Cells only exist on a Marine Air Ground Task Force staff, but subordinate maneuver units lack an organization to integrate spectrum warfare.

In contrast, the Navy centralizes this function in every tactical formation through the Information Warfare Commander. Marine Corps maneuver units require an integrated spectrum warfare role to function in a manner similar to the Navy’s Information Warfare Commander, to fuse spectrum warfare operations and assure information superiority. At the tactical level, communications and electronic warfare functions would be combined under a spectrum officer with responsibility for all electromagnetic emissions.

Ground and air units at the battalion and squadron level should have full-time planners trained to integrate friendly command and control networks with electronic attack, protection, and support activities in real-time. This requires a centralized organization with links to distributed maneuver units. The Army has experimented with multi-domain task forces since 2017, combining intelligence and information operations with space and cyber. Accordingly, every maneuver element, down to the platoon, must possess spectrum awareness capability. This gap is not exclusive to ground forces. Aviation units have also noted persistent challenges aggregating the vast quantities of data in the information environment.

#3 Hardware: Replace the Systems

“Today we generally use the EM spectrum and cyberspace as an enabler for land, sea, air, and undersea operations. We have not yet taken full advantage of the warfighting potential afforded by the merging of the EM spectrum and cyberspace, or the pervasiveness of the EM spectrum into every facet of military operations.”—Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan W. Greenert

If Marine (and Navy) units dispersed across the littorals are to have a fighting chance, the Marine Corps must upgrade its command and control systems for greater survivability. The U.S. Army is heavily investing in this effort, to include a new alternative system to GPS location and timing. The Army is also leaning forward in fielding new electronic warfare systems at the tactical level. While hardware upgrades are an expensive undertaking, the alternative for inaction will be grim on the modern battlefield. While the Marine Corps is experimenting with minimal command posts, currently fielded command and control systems are nowhere near adequate. This effort should include all radios and waveforms without resiliency or survivability characteristics in a contested spectrum environment, such as jam resistance, and low probability of intercept and detection.

The speed at which modern digital electronics can shift operating modes and techniques has vastly increased. Proven systems and waveforms are available today: SATURN waveform to replace HAVEQUICK, Mobile User Objective System for satellite communications on the move, hand-held Link-16 to enable ground forces to link with aviation networks, and the AN/PRC-160 to replace legacy High Frequency radios. Many other new anti-jam, anti-spoof commercial systems are available on the market capable of operating across a range of frequencies. For the cost of one F-35B, the Marine Corps can field 5,000 next generation radios, improving the survivability of hundreds of maneuver elements.

Second, Marine Corps units need tools to dynamically manage the spectrum. A commander today at the tactical level has no situational awareness in the electromagnetic spectrum. Without a common spectrum picture, communicators cannot coherently sense or map the spectrum in real-time, and information cannot provide commanders the ability to make informed decisions. Hardware and software exists to enhance network visibility into a fused display, but over the years program officers have not fielded a common system. Spectrum visualization and RF Mapping tools, such as Radio Map, can provide real-time awareness of the spectrum at the tactical level. The Army has also recently developed a quantum sensor capable of detecting the entire radio-frequency spectrum.

Spectrum warfare becomes more complicated for Marines operating from ship to shore. Shipboard systems are controlled by the Navy, and often even older than tactical Marine Corps systems operated ashore. This paradigm has to change if sailors and Marines are to fight across the Indo-Pacific and rely on “any sensor, any shooter” as the Joint All Domain Command and Control concept envisions.

Third, establish Marine Corps-wide interoperability standards, and work closely to synchronize efforts with the wider joint force. Marine Corps Program Managers routinely field distinct systems that cannot share information, and it gets worse when factoring in NAVAIR, which owns all naval aviation systems. There must be an individual coordinating authority for command and control, to include electronic warfare sensors, across the service with guidance and direct access to Navy program offices to ensure unity of effort.

The Army is investing heavily in electronic warfare, and has wisely established a suite of open architecture standards for added flexibility and interoperability between requirements for intelligence gathering, electronic warfare, and communications links. As one of the Defense Department’s leaders recently noted, the ability to integrate information is perhaps a culture problem first.

Fourth, pursue systems with the capability to send and receive data through local telecommunications networks. For example, Marines or sailors in the littorals will operate in and among high density civilian populated areas with existing cellular and wireless telecommunication infrastructure. Leveraging these networks will be akin to finding a needle in a stack of needles. This technology is currently available, and has been in use for years by organizations within the Department of Defense.

Finally, equip units ashore and afloat with passive and low-power sensors, and invest in laser and light-based transmitters, which offer significantly reduced signatures. None of these activities should be undertaken without close coordination with the Navy, and the joint force. Imagine an autonomous electronic decoy launched by a Marine unit in the littorals, prompting a kinetic strike on the decoy by an Army or Navy platform, thereby unmasking themselves and revealing their position.

Conclusion

“So the third principle, this is the combination of guided munitions and informationalized warfare, will span all types of ground combat, a regular, hybrid, nonlinear, state proxy and high-end combined-arms warfare. And that means, like the Israelis found out, that the foundation for ground force excellence is going to be combined-arms operational skill.”—Bob Work, former Deputy Secretary of Defense

Force Design is an opportunity for the Marine Corps to improve its ability to maneuver in the electromagnetic spectrum – on offense and defense. This requirement is a historical road block for the technologically challenged Marine Corps. As historian Allan Millett has written, “The challenge facing the Marine Corps is whether its military culture, based on human qualities… can adjust in a war dominated by microchips.” On the modern battlefield, Marines ashore and afloat must practice spectrum warfare for survivability, and to maintain information superiority. To compete in this modern paradigm, the Marine Corps must update training and education, modernize command and control systems, and re-organize functional areas for spectrum integration.

As the joint force seeks to move toward a highly dynamic and fluid “all-domain” warfare, the Marine Corps must achieve unity of effort across all functions, especially communications and electronic warfare. We must stop admiring the problem and settling for incremental change. A holistic review of the information environment at the tactical level is in order, with a focus on the people, ideas, and hardware needed for information superiority. As Commandant Berger and General Brown recently acknowledged, investment in “truly all-domain command and control” must be accelerated.

Information superiority alone does not guarantee success in war. But if long-range precision strike and distributed forces are critical requirements, then information superiority is essential. This means critical vulnerabilities – command and control systems – must be protected. Marines will be vastly more lethal and survivable – a more credible threat – with integrated spectrum organization, modern systems, and updated training and education.

Maj. Nick Brunetti-Lihach is a Marine Corps Communications Officer currently serving as Operations Officer, Marine Wing Communications Squadron 28. He has deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Marine Corps or the Department of the Navy.

Featured image: U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Jacory Calloway, a radio operator with 1st Battalion, 2d Marine Regiment, sets up a long range communication system while demonstrating expeditionary advanced basing capabilities Oct. 7 to 8, 2020, as part of Exercise Noble Fury. (U.S. Marine Corps photos by Cpl. Josue Marquez)