By David Scott

China presents a paradox—a significant actor with direct interests and presence in the Red Sea, but one that has played a minimal role in the unfolding Red Sea crisis. This crisis is a result of attacks on shipping in the Red Sea, carried out by the Iranian-backed Houthis in solidarity with Hamas. These attacks have been ongoing since November and show little sign of abating. China has maintained a studied and deliberate distancing from the issue, whose strategic inaction rather than action has been noticeable. A close scrutiny of Chinese strategy and announcements follows.

China’s Interests and Presence

China’s strategic interest in the Red Sea is two-fold – geo-economic and geopolitical. On the geo-economic front, China is interested in stable maritime trade routes. This includes energy flows from the Middle East and Mediterranean eastwards back to China, and westward flows of Chinese imports and exports to Europe. Disruption of such flows is not something that China particularly wants. Both of these aspects are closely connected with China’s Maritime Silk Road (MSR) initiative, which in going from the Indian Ocean into the Mediterranean passes through the Red Sea. All of the Red Sea littoral states (Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti) have signed up for the Maritime Silk Road. The Suez Canal, Red Sea, and Gulf of Aden are “essential” to the success of China’s MSR.

On the wider geopolitical front, China has strong strategic links with Iran. Both countries are lending support to the Russian war effort in Ukraine, for which the Red Sea has become an important corridor for Russian supplies. China continues to illicitly buy 90 percent of Iran’s oil, thereby helping Iran finance the Houthis and other proxy groups in the Middle East. Hence the Politico headline in March 2024, “How China ended up financing the Houthis’ Red Sea attacks.” China’s other persistent strategic interest was accurately summed up by Ron Alterman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who pointed out in February 2024 that the Red Sea Crisis shows that “Beijing’s main regional focus remains undermining the United States.”

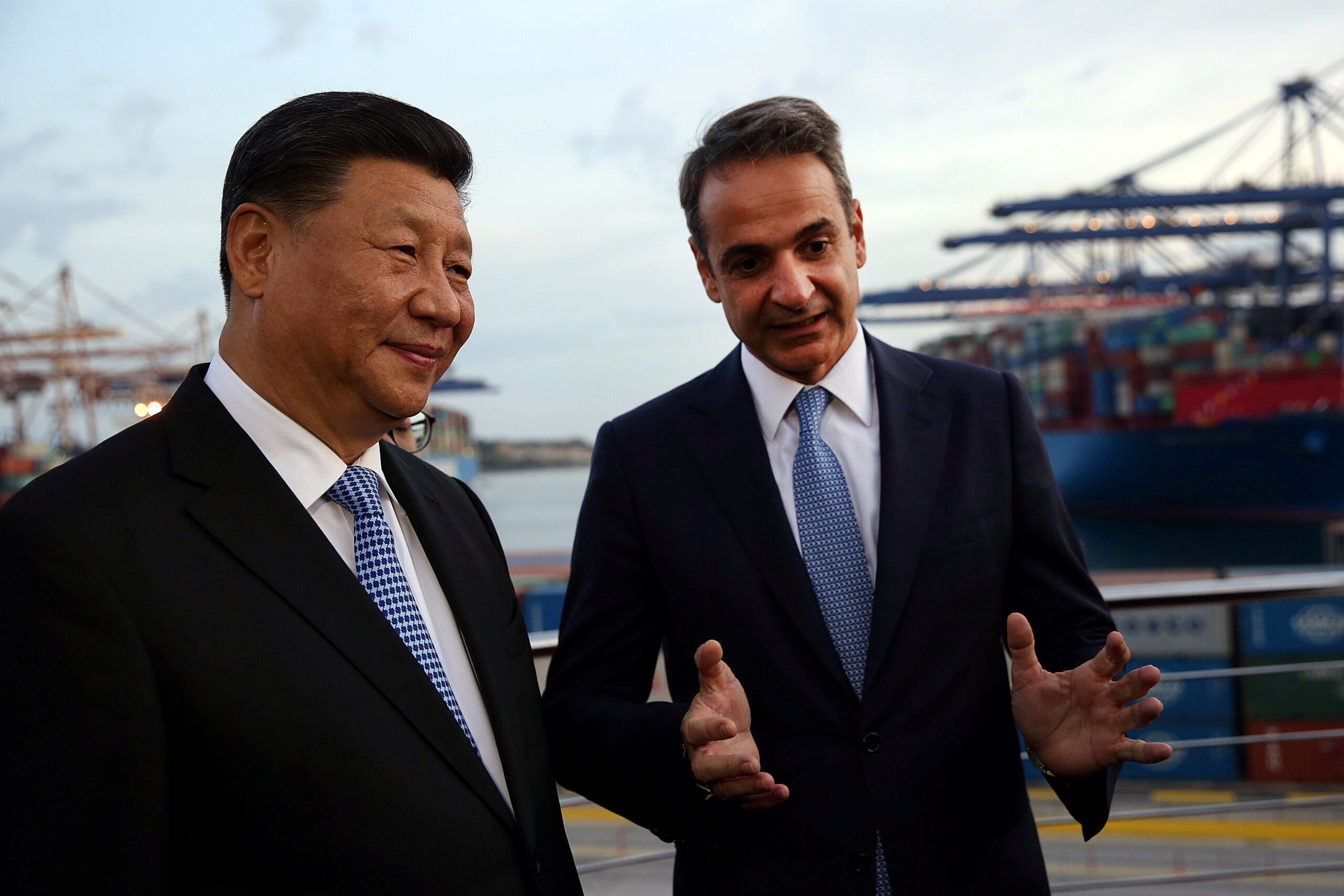

China’s presence in the region is multifaceted. In the Western Indian Ocean, it has privileged port access at Gwadar, Pakistan, where China Overseas Ports Holding Company Limited (COPHC) has a 40-year agreement running from 2013–2053. It has a similar arrangement in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, where China Merchant Ports has an agreement in effect from 2017–2106. In the Eastern Mediterranean, the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) has a 67 percent share in the running of Piraeus, Greece referred to by President Xi Jinping as the “Dragon’s Head” in his 2019 visit to Greece. If Piraeus is the “Dragon’s Head,” then the Red Sea is the neck linking the Indian torso of the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean head.

China is involved on both shorelines of the Red Sea. At one end of the Red Sea, China has a 20 percent stake in the running of Port Said in Egypt, and a 25 percent share in the running of Ain Sokhna, also in Egypt, bought in March 2023. Dekhila has also been identified as a further site for Egyptian-Chinese port collaboration. 2023 saw a $6.75 billion deal between Egypt’s Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCEZ) and China’s state-owned China Energy Engineering Corporation (CEEC) to develop green ammonia and green hydrogen projects. China Harbor Engineering Company has been confirmed as the winning bidder to build the new container terminal at Jeddah Islamic Port in Saudi Arabia. China has also established itself as the single largest lender to Eritrea, including financing a 500-kilometer (311-mile) road between Massawa and Assab ports.

At the other end of the Red Sea, China established a military base at Djibouti, operating since 2017. That said, China does not have a monopoly given that the U.S. and France, as well as Italy, Spain, and Japan also have military bases in Djibouti. China is also involved in Djibouti in developing the port of Doraleh, at a time when dept dependency (and future debt swaps on the model of Gwadar and Hanbantota) loom for Djibouti. Finally, agreements were inked in June 2023 for China to develop a satellite launch center at Obock, adding further Chinese presence at the entrance to the Red Sea.

China’s presence is also a matter of naval deployments. Over the last decade, the Chinese Navy has increasingly deployed across the Indian Ocean, with further extensions up the Red Sea and into the Mediterranean at times. Chinese naval vessels have deployed for two primary purposes. One is participation in naval exercises with Pakistan and Iran. The second is the anti-piracy patrol mission running since 2008 in the Gulf of Aden, aimed at piracy emanating from Somalia and East Africa.

On February 21, the 46th fleet of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) sailed for the Gulf of Aden mission. This unit consisted of the guided missile destroyer Jiaozuo, the missile frigate Xuchang, and the replenishment vessel Honghu. Over 700 officers and sailors were on board, along with two helicopters. Their mission was to replace the 45th fleet, which was a similar three-ship cohort that was stationed in the Gulf of Aden since September 2023.

The 46th Fleet took over escort missions in the Gulf of Aden and waters off Somalia from the 45th Fleet on March 4. The 46th fleet’s first escort duty was to escort the Chinese general cargo ship Kaituo of COSCO to a designated point in the Gulf of Aden. Ministry of National Defense spokesperson Zhang Xiaogang “dismissed links” between Gulf of Aden escort missions and the Red Sea crisis, explaining on February 29 that “the PLAN task groups conduct routine escort operations in the Gulf of Aden and waters off Somalia. The recent deployment has nothing to do with the current situation in the region.” The 46th fleet carried out a combat training mission on April 5, but again with no reference to the Red Sea or the Houthis, and indeed with little regard to piracy.

As to the 45th Fleet, it turned eastwards away from the Red Sea, instead moving across the Arabian Sea to take part in trilateral exercises with Russia and Iran in the Gulf of Oman from March 11-15. Their trilateral exercise, Maritime Security Belt, had little to offer on the Houthi threat in adjacent waters, but sent a wider message to the U.S. and its allies.

With these resources and facilities established in the area, China could intervene militarily in the Red Sea crisis if it chose, or at least increase its deployments, such as India has done. Yet there has not been such Chinese action. Instead, calculated strategic inaction has been evident.

Criticizing the U.S.

At first China ignored the Red Sea crisis. At the initial meeting of the China-Saudi Arabia-Iran trilateral joint committee on December 15, 2023, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi met his Iranian and Saudi counterparts, but with no particular discussion given on the Red Sea crisis.

In contrast, the December 18 announcement of the U.S.-led Operation Prosperity Guardian was met with immediate Chinese criticism. A December 19 editorial appeared in the Chinese state media outlet Global Times under the title, “Can the US-led joint patrols defuse the Red Sea alert?” It denounced the U.S. for its “hegemonic needs,” and argued that the U.S. initiative would fail unless it addressed the “butterfly effect” of the Red Sea crisis as “spillover effects of the Palestine-Israel conflict,” for which a ceasefire was needed. Another Global Times editorial headline put it simplistically, “If U.S. can clear way for ‘cease-fire in Gaza,’ Red Sea problem would be solved.” Nevertheless, as a precaution, on December 19 COSCO announced a halt to shipments through the Red Sea.

That same day, U.S. State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller said that while Houthi attacks on international shipping “harm the United States; they [also] harm China,” such that “we would welcome China playing a constructive role in trying to prevent those attacks from taking place. I will let the Chinese foreign ministry speak to their side of that conversation and any steps that they might have taken.” There are two problems with this line of argument. Firstly, Houthi attacks do not harm China to the same extent they harm the U.S. and the West. Secondly, the tense was future conditional, China has not actually been particularly constructive over the issue, and has shown little proof of steps taken.

China’s Inaction

Why did China choose not to involve itself in the U.S.-led operation? Chinese logic was clearly espoused by Zhao Ziwen and Jevans Nyabiage, arguing in a South China Morning Post December 28 editorial that China would not take part unless its own ships were threatened. One simple reason is that Chinese ships have not been attacked. Indeed, such ships have been actively transmitting their “all Chinese crew” to gain unmolested passage by the Houthis. Even if Chinese ships were being attacked, it is hard to imagine that China, for reasons of national sovereignty and pride, would subsume itself under a U.S.-led operation.

The next indicator of calculated Chinese strategic inaction was with the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2772 passed on January 10, 2024. The resolution had three significant parts. Sections 2 “Demands that the Houthis immediately cease all such attacks,” section 3 referred to member states’ right “to defend their vessels from attacks,” and section 4 commended “efforts by Member States within the framework of the International Maritime Organization, to enhance the safety and secure transit of merchant and commercial vessels of all States through the Red Sea.” China’s stance towards the resolution was abstention.

Using the self-defense option presented by section 3, on January 12, the United States and the United Kingdom quickly launched a series of air and missile strikes against the Houthis. Equally quickly, China positioned itself against the U.S.-U.K. strikes. China’s general approach was immediately clear in its state media headlines – “Impossible to restore peace to the Red Sea via military means” (Global Times, January 12), and “UNSC has not authorized force against Yemen” (Global Times, January 13).

The following day, January 14, a Joint Statement between China and the Arab League showed selective positioning:

“Expressing profound concern over the recent escalation in the Red Sea, both parties underscored the paramount importance of upholding Yemen’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Ensuring the safety of international commercial shipping lines in the Red Sea was deemed crucial.”

The disconnect between the first and second propositions are obvious, with action against Houthi capability in Yemen necessary to an extent to secure shipping. Chinese state media continued to be selective and sharp, in headlines like, “US escalates Red Sea tensions, while China voices fairness” (Global Times, January 16).

Cooperation with Iran

China’s approach has been to seek tacit clearance in advance for its shipping. A Reuters report cited some Chinese pressure exerted on Iran in early January, with an Iranian official revealing that, “Basically, China says: ‘If our interests are harmed in any way, it will impact our business with Tehran. So tell the Houthis to show restraint.’” What became clear was this restraint was aimed towards China rather than the West. This was made more clear with the January 19 announcement by Houthi spokesman Muhammad al-Bulheiti that “Russia and China, their ships will not be threatened, [but will have] securities for their safe passage through the Red Sea.”

There is also a reverse incentive for China to increase its traffic through the Red Sea. Lloyd’s List indicated that while containership transits through the Red Sea have plunged since November, the proportion of China-linked tonnage has surged, much of it involving trade with Russia. In an “opportunistic” move, smaller Chinese companies like Sea Legend Shipping have sent ships to serve the smaller Red Sea ports, including Doraleh in Djibouti, Aden in Yemen, Hodeidah in Yemen, Jeddah and Aqaba in Saudi Arabia, and Sokhna in Egypt. The Qingdao-based Sea Legend Shipping also announced Red Sea transit trips in January.

Faced with reports that China had asked Iran to help rein in Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, China’s Foreign Ministry argued on January 26 that:

“Our position on the situation in the Red Sea is clear. We are deeply concerned about the recent escalating situation in the Red Sea. The Red Sea is an important international trade route for goods and energy. From day one, China has actively deescalated the situation, called for an end to the disturbance to civilian ships, and urged relevant parties to avoid fueling the tensions in the Red Sea and jointly protect the safety of international sea lanes in accordance with the law. What must be underlined is that the tensions in the Red Sea are a spillover of the Gaza conflict, which should end as soon as possible to prevent it from escalating or spiraling out of control. The UN Security Council has never authorized the use of force by any country against Yemen. The sovereignty and territorial integrity of Yemen and other coastal countries along the Red Sea need to be earnestly respected. China stands ready to work with all parties for the de-escalation of the situation and security and stability of the Red Sea.”

There was absolutely no indication of what exactly China was proposing by the phrase “jointly protect the safety of international sea lanes in accordance with the law.” Is China referring to joint patrols, joint calls, joint interventions? Jointly with who? It also remains unclear how China has been “actively” trying to de-escalate the situation.

U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s meeting with China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi from January 26-27 included the Middle East as a topic, but without any indication by either the U.S. or China on specific discussion, let alone agreement, concerning the Red Sea. The crisis was explained by the South China Morning Post on January 26 as “too important to avoid but too sensitive to mention given the stakeholders involved.” China was very aware of its advantageous position, with state media headlines like, “If the US needs China in Red Sea, it should talk to China nicely,” (Global Times, January 26) and that “Red Sea tension shows US’ weakening in global affairs,” (Global Times, February 1). The Houthi linkage to the Gaza crisis continued to be used by China, with state media headlining “US airstrikes on Houthis can’t stop Red Sea crisis ‘as root cause in Gaza remained unsolved,’” (Global Times, February 4).

The South China Morning Post reported a pact on March 22 between the Houthis, Russia, and China, where Russian and Chinese ships would not be targeted by the Houthis. The pact was drawn up by Russian and Chinese diplomats in Oman, meeting with Mohammed Abdel Salal, a leading political figure of the Houthis. The quid pro quo tradeoff was future political support to the Houthis by Russia and China in UN Security Council deliberations. When questioned on March 22, China’s Foreign Ministry did not deny such an agreement, but refused to give any details of such discussions and tradeoffs.

Ironically, over that same weekend, the Houthis launched five anti-ship ballistic missiles into the Red Sea in the vicinity of M/V Huang Pu, a Panamanian-flagged, Chinese-owned, Chinese-operated oil tanker 23 nautical miles west of Mokha. China’s Foreign Ministry response to this Houthi error was minimal:

“China always opposes harassment against civilian ships and stands for keeping the shipping lanes in the Red Sea safe in accordance with international law. Meanwhile, China believes that the international community needs to work for an early end to the fighting in Gaza and create necessary conditions for the de-escalation of the situation in the Red Sea. China will continue to play a constructive role and strive for the early restoration of peace and tranquility in the Red Sea.”

The lack of specific protest, let alone direct response was telling. The tenuous cover story of linking Houthi actions to the Gaza situation was maintained by China. While the Gaza conflict may have helped precipitate the Red Sea crisis, resolution in Gaza does not guarantee a resolution in the Red Sea. The Houthi campaign in the Red Sea may have very much taken on a life of its own, independent of the conflict between Hamas and Israel.

Win-Win Strategy and Wider Dynamics

To use Chinese terminology, U.S. operations against the Houthis present China with a win-win situation, an uncomfortable outcome for Western policymakers. In a “free riding strategy” by China, if Western countermeasures are successful in getting the Houthis to stop their attacks, then broader Chinese interests are served by restoring unfettered trade flows through the Red Sea, while the U.S. and U.K. attract local opprobrium from having carried out the mission. If Western countermeasures are unsuccessful then China gains a bigger share of Red Sea trade by virtue of its agreement with the Houthis, while the shipping of other actors must either risk attack or face less economical journeys around the African continent.

The Houthis’ participation in Iran’s large-scale strike against Israel on April 13, some of which was shot down by U.S. and U.K. forces, provides an uncomfortable reminder of the wider dynamics of the Red Sea crisis. The Chinese Foreign Ministry response on April 14 was innocuous but revealing: “China calls on the international community, especially countries with influence [i.e. the U.S.] to play a constructive role for the peace and stability of the region,” and that “the ongoing situation is the latest spillover of the Gaza conflict. There should be no more delays in implementing UN Security Council Resolution 2728 and the conflict must end now.”

This is exactly the same line played by China with regard to the Red Sea Crisis. It was telling that on April 14 the Global Times similarly called for calm and restraint, while describing Iran’s April 13 assault that featured more than 300 drones and missiles as “restrained.” It went on to criticize U.S. “one-sided” support for Israel. Houthi participation was ignored.

Dr. David Scott is an associate member of the Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies. A prolific writer on Indo-Pacific maritime geopolitics, he can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

Featured Image: Sailors man the rail as the guided-missile destroyer Yinchuan (Hull 175) steers to the replenishment position alongside the comprehensive supply ship Weishanhu (Hull 887) during the first underway replenishment (UNREP) conducted by the 34th Chinese naval escort taskforce in eastern waters of the Gulf of Aden on February 3, 2020. (Photo by Cai Shengqiu/eng.chinamil.com.cn)