By Kyle Cregge

What if the final frontier is much closer to home? From SpaceX to Space Force, many groups are seeking to dominate space in an era of Great Power Competition and commercialization. Yet for all the time humans have looked up, a far murkier domain below remains largely unexplored. The deep-sea and seabed remain less understood than our near abroad in space and yet contain myriad natural resources which have yet to be tapped. Beyond the familiar reserves of hydrocarbons, there are metallic nodules and crusts spread across the seabed, resting beneath national exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and claimed continental shelves, as well as below the high seas.

China, meanwhile, maintains a near-monopoly on the rare-earth metals that sustain the modern global economy and regularly leverages these key resources through coercive bilateral sanctions. Amidst these challenges, the private sector and public investment of many other nations will likely turn to the seabed to diversify their supply chains. Environmental risks, scientific opportunities, and assent to untested international law remain open questions in these extractive ventures, but seabed mining is coming regardless. The US Coast Guard’s similar and enduring missions around maritime resource extraction make it well-suited to enforce domestic and international law in this expanding industry. The service should prepare for seabed mining by engaging with allies and partners and by supporting scientific research and environmental protection.

The Opportunity of Seabed Mining

Deep seabed mining is generally defined as extracting resources below a depth of 200 meters, such as the deep-sea polymetallic nodules first recorded by the HMS Challenger Expedition of 1872-1876.1 Private citizens and companies have intermittently attempted to capitalize on the potato-sized concretions over the past 150 years. These ambitions even served as the elaborate cover story between Howard Hughes and the CIA for the ship Glomar Explorer and the plan to recover the sunken Soviet submarine K-129 off the coast of Hawaii in 1974.2 More recently, the multinational firm Nautilus Minerals went bankrupt in 2019 following a decade’s worth of planning and investment to drill off the coast of Papua New Guinea for copper, gold, silver, and zinc contained within seafloor massive sulfide (SMS) deposits.3 Despite the legal and financial trouble Nautilus Minerals encountered, the bounty from mining the seabed will continue to encourage innovation and investment. While estimates vary, proposals have put the potential annual contributions of the deep-sea mining industry to the US economy at up to $1 trillion, and the value of all gold deposits alone worth up to $150 trillion.4 Compared to the value of US commercial fisheries – $5.6 billion in 2018 – seabed mining could be orders of magnitude more profitable.5

As part of its coercive economic diplomacy, China has selectively complicated foreign supply chains through export restrictions on rare earth metals.6 Long a recognized strength for China, former leader Deng Xiaoping stated in 1992, “The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths,” and his assessment has only continued to bear out to today. The communist nation currently supplies 95% of the global rare earths output and has used its virtual monopoly as a thinly-veiled economic weapon during diplomatic disputes with Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines in the last decade.7 The US imports up to 80% of its rare earths from China. Those resources feed into critical defense systems like guided missiles, lasers, and fighters like the F-35 Lightning II, which requires up to 920 pounds of rare earths during the production of each aircraft.8 The F-35 is currently in use or on order by fifteen countries that are currently European or Indo-Pacific partners or allies of the United States.9 Expanding beyond the single aircraft system, deliberately reduced rare earth exports could threaten each of these nation’s military modernizations. Whether for profit or supply chain preservation, America and its allies will likely look to the seabed to help meet these demands.

Why the Coast Guard?

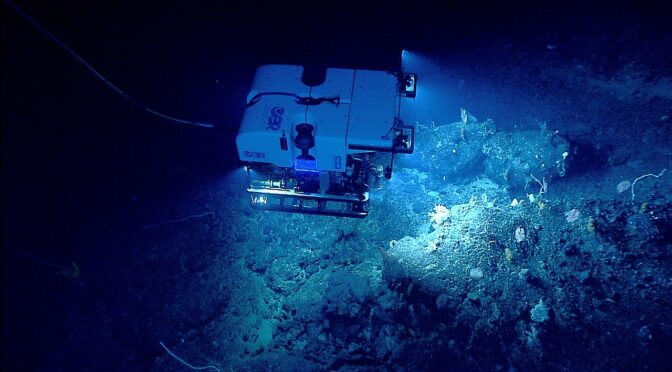

Seabed mining requires a coordinated surface support infrastructure akin to hydrocarbon exploration and extraction, which is an oversight role the Coast Guard knows well. Robot tractors, unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), and other seafloor collectors will mine from seamounts or collect nodules deep below,10 feeding those resources up through a flexible riser pipe for refinement and processing, while a return pipe feeds the non-desired sediment and waste back to the seafloor.11 Barges and bulk carriers will then receive the collected seabed resources from the production support vessel and transfer them back to a port of call for further use. Additional remotely-operated vehicles (ROVs) will be launched from commercial ships on the surface to provide seabed surveillance, conduct scientific research, and monitor environmental impacts as part of the broader operation.

Just like the Coast Guard’s presence missions for domestic fisheries, cutters will represent US mining interests within and beyond the nation’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), though some national rights to seabed resources reach out to the extended continental shelf (ECS). As the Vision to Combat Illegal, Unregulated, or Unlawful (IUU) Fishing states:

The U.S. Coast Guard has been the lead agency in the United States for at-sea enforcement of living marine resource laws for more than 150 years. As the only agency with the infrastructure and authority to project a law enforcement presence throughout the 3.36 million square mile U.S. EEZ and in key areas of the high seas, the U.S. Coast Guard is uniquely positioned to combat IUU fishing and uphold the rule of law at sea.12

While seabed resources are not living, domestic and international law similarly govern their extraction – and mining will require the same sort of maritime regulation. American domestic justification follows from the 1980 Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resource Act (DSHMRA), which claimed the right of the US to mine the seabed in international waters, and specifically identifies the Coast Guard as responsible for enforcement.13

International Law and Engagement

Internationally, the Coast Guard will face the same problem the US Navy does with its freedom of navigation operations in places like the South China Sea. Through the presence of its surface vessels, the services seek to reinforce the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as reflecting customary international law, while the US is not itself a party to the treaty. The US Senate has thus far avoided treaty ratification to avoid potentially surrendering sovereignty around seabed mining regulation to the International Seabed Authority (ISA), based in Kingston, Jamaica.14, 15

Formed in 1994, the organization retains responsibility under the United Nations for administering “The Area,” of the seabed beyond any nation’s EEZ.16 Because the US is a non-party state to UNCLOS and an observer, vice member, of the ISA, US companies must either pursue mining operations through another sponsor state under the ISA regime or operate outside the ISA’s purview based on US domestic law interpreted within the framework of UNCLOS. These complications are not the Coast Guard’s fault, nor is the service responsible to necessarily fix them. But given the intersection of maritime law enforcement, commercial resource extraction, and the desire for non-military engagement, the Coast Guard is far better suited than the US Navy in a “seabed maritime presence” role.

The seabed is likely the next domain for competition over a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” and a “rules-based international order.” Among the most challenging in a future seabed competition would be China and Russia, states that have already used lawfare in the South China Sea and Arctic regions respectively to pursue their territorial gains. The two great powers may use the same playbook in the deep sea both in practice and through the ISA. The ISA has authorized 30 total contracts for exploration in The Area, and 16 are within the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). The CCZ is a vast plain spanning over 3,000 miles of the central Pacific Ocean southeast of Hawaii which contains a vast supply of polymetallic nodules. Two separate Chinese and Russian companies have each received 15-year contracts from the ISA for 75,000 square kilometer areas for future exploration, in addition to areas on the Southwest Indian Ridge and Western Pacific for China specifically.17 No nation has yet indicated a serious move to begin commercial exploitation in The Area, but as the technology matures, China may seek to extend its rare earths monopoly and start mining throughout the Indo-Pacific.

While the US has claimed four tracks within the CCZ under its domestic law, it too has not yet begun commercial exploration.18 Yet there are numerous opportunities for theater engagement and for ensuring seabed mining practices are in accordance with international regulations. The Coast Guard’s enduring support to allies and partners for fisheries enforcement should naturally be mirrored to the seabed – particularly for Pacific nations. Many of the same island nations and territories working on IUU fishing are evaluating deep-sea mining ventures to stimulate their economies within their EEZs and out into the CCZ.

The Pacific island nations Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and the Cook Islands all have active seabed licenses to explore within their EEZs. For US allies and partners, six of the top nine largest national EEZs are western or democratic nations, with a total area larger than the continent of Asia.19 This presents a vast potential bounty for seabed mining. With its long history working with international coastal forces, the Coast Guard remains the most capable service to demonstrate American commitment to a rules-based international order across various future seabed mining ventures.

Preserving the Seabed Environment

The Coast Guard’s responsibility to support and enforce proper seabed mining will also be a natural outgrowth of its other enduring missions to support scientific research and environmental protection. As it has done with polar icebreaker missions, the Coast Guard routinely explores new domains with scientists and experts on board.20 The seabed requires further study, as a mere 20% of the global ocean has been mapped at better than a kilometer grid resolution, and the previous administration specifically directed the White House’s Ocean Policy Committee to develop a strategy to map the remaining 60% of unmapped American EEZ.21, 22 From what has been mapped, the seabed’s biodiversity is immense. Of the estimated 0.01% of the explored area of the CCZ, scientists have collected more than 1,000 animal species, of which 90% are believed to be new or undescribed. This tally does not account for over 100,000 potential microbe species.23 The Coast Guard can both support this research from its cutters and support its enduring statutory mission of Environmental Protection as well.24

Early studies have proposed immense risks to seabed environments from mining. Habitat loss, sediment smothering of seabed animals following resource processing, and issues of light, noise, or other vibrations are all significant concerns for unique resources and animals which have evolved over millions of years. If calls for an international moratorium on mining are ultimately ignored, the US should not leave China or Russia to shape the best practices for seabed mining.25 The US Coast Guard can be present and use its cutters or even onboard UUVs to monitor that mining practices are in accord with any standing international agreements to best preserve the environment.

A Deep Future for the Coast Guard

The Coast Guard has time to critically analyze its role in future seabed mining ventures but must consider the development of new service capabilities and build inter-agency bridges. Force structure assessments could partner with the Navy on multiple capability areas. UUVs operating at various depths could serve ongoing submarine force objectives while supporting Coast Guard mining monitoring requirements. If the Coast Guard determined it needed a larger platform for sustained presence and multi-helo or UUV deployment at a mining site, the Expeditionary Staging Base (ESB) could serve as a cheaper, known option from which to iterate. Regardless of platform, operations in the CCZ or broader Pacific would present a taxing operational requirement, given its distance from Hawaii and the necessary logistics train, compared to the service’s more common littoral missions.

To meet this demand signal, civilian policymakers must ensure that any profits associated with domestic commercial seabed mining would be taxed with a sufficient funding line to support the shipbuilding, logistics, command and control, and research and development in support of the Coast Guard seabed presence mission.

The Coast Guard must also strive to build its inter-agency relationships around seabed mining. The service is already a member of the State Department’s Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) Task Force, an inter-agency government body that already focuses on seabed issues.26 But the ECS Task Force is primarily focused on identifying the limits of the US Continental Shelf through geological survey and legal analysis; projections of national seabed mining objectives must go further. Beyond the interagency and joint force, the Coast Guard should liaise with academia, non-governmental and international organizations, and the private sector to contextualize the service’s future role. Each will have their initiatives and interests, but collectively they will better prepare the Coast Guard to engage with the seabed.

The Coast Guard has yet to be tasked to support presence, international maritime law enforcement, scientific research, or environmental protection with respect to seabed mining. Yet it has done those same types of missions on the surface for hundreds of years. While the commercial industry is developing its technologies and processes, the Coast Guard should project its role into the deep domain given its historic missions and requirements. Challenges abound, from international economic drivers to future science and environmental research. Working collaboratively, the Coast Guard can lead a network of partners to strengthen economic and maritime security around seabed mining, thereby promoting the rules-based international order and a free and open Indo-Pacific. Looking forward, the Coast Guard must look deeper to win on the seabed and in the future.

Lieutenant Kyle Cregge is a surface warfare officer. He served on a destroyer, cruiser, and aircraft carrier as an air defense liaison officer. He was selected by Carrier Strike Group 9 for the 2019 Junior Officer Award for Excellence in Tactics. He currently is a master’s degree candidate at the University of California San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy.

Endnotes

1. Scarminach, Shaine. 2019. “Diving Into The History Of Seabed Mining – Edge Effects”. Edge Effects. https://edgeeffects.net/seabed-mining/.

2. “The Secret On The Ocean Floor”. 2021. Bbc.Co.Uk. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/deep_sea_mining.

3. “Nautilus Minerals Officially Sinks, Shares Still Trading”. 2019. MINING.COM. https://www.mining.com/nautilus-minerals-officially-sinks-shares-still-trading/.

4. “Deep-Sea Mining Could Provide Access To A Wealth Of Valuable Minerals”. 2021. Theneweconomy.Com. https://www.theneweconomy.com/energy/deep-sea-mining-could-provide-access-to-a-wealth-of-valuable-minerals.

5. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2020, February 21) Fisheries of the United States, 2018. Retrieved

from NOAA Fisheries: www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/fisheries-united-states-2018

6. Vekasi, Kristin. 2021. “Will China Weaponise Its Rare Earth Edge? | East Asia Forum”. East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/03/25/will-china-weaponise-its-rare-earth-edge/.

7. Tiezzi, Shannon. 2021. “Is China Ready To Take Its Economic Coercion Into The Open?”. Thediplomat.Com. https://thediplomat.com/2019/05/is-china-ready-to-take-its-economic-coercion-into-the-open/.

8. Narayan, Pratish and Deaux, Joe. ” U.S. Fighter Jets and Missiles Are in China’s Rare-Earth Firing Line”. 2021. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-29/u-s-fighter-jets-and-missiles-in-china-s-rare-earth-firing-line.

9. Pawlyk, Oriana. 2021. “Switzerland Becomes Latest Nation To Choose F-35 For Its Next Fighter Jet”. Military.Com. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2021/06/30/switzerland-becomes-latest-nation-choose-f-35-its-next-fighter-jet.html.

10. “Deep-Sea Mining”. 2018. IUCN. https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/deep-sea-mining.

11. Ibid.

12. Admiral Karl L. Schultz. “The United States Coast Guard’s Vision to Combat IUU Fishing”. September 2020. https://www.uscg.mil/Portals/0/Images/iuu/IUU_Strategic_Outlook_2020_FINAL.pdf

13. “30 U.S. Code Chapter 26 – DEEP SEABED HARD MINERAL RESOURCES”. 2021. LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/30/chapter-26.

14. Ibid.

15. Verma, Aditya Singh. “A Case For The United States’ Ratification Of UNCLOS”. 2020. Diplomatist. https://diplomatist.com/2020/05/02/a-case-for-the-united-states-ratification-of-unclos/.

16. “About ISA | International Seabed Authority”. 2021. Isa.Org.Jm. https://www.isa.org.jm/about-isa.

17. “Minerals: Polymetallic Nodules | International Seabed Authority”. 2021. Isa.Org.Jm. https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/polymetallic-nodules.

18. Groves, Steven. “The U.S. Can Mine The Deep Seabed Without Joining The U.N. Convention On The Law Of The Sea”. 2021. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/report/the-us-can-mine-the-deep-seabed-without-joining-the-un-convention-the-law-the-sea.

19. Migiro, Geoffrey, World Facts, Countries Zones, All Continents, North America, Central America, and South America et al. 2018. “Countries With The Largest Exclusive Economic Zones”. Worldatlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-with-the-largest-exclusive-economic-zones.html.

20. Ensign Evan Twarog and Lieutenant (J.G.) Cody Williamson, “Polar Security Cutters Will Face An Evolving Arctic”. 2021. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/january/polar-security-cutters-will-face-evolving-arctic.

21. Amos, Jonathan. “One-Fifth Of Earth’s Ocean Floor Is Now Mapped”. 2020. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-53119686.

22. Cornwall, Warren. “Trump Plan To Push Seafloor Mapping Wins Warm Reception”. 2019. Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/11/trump-plan-push-seafloor-mapping-wins-warm-reception.

23. Heffernan, Olive. “Seabed Mining Is Coming — Bringing Mineral Riches And Fears Of Epic Extinctions”. Nature.Com. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02242-y.

24. Commander Sharon Russell and Lieutenant James Stevens. “The Coast Guard Can Take On DoD Environmental Response Duties”. 2020. U.S. Naval Institute. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2020/february/coast-guard-can-take-dod-environmental-response-duties.

25. Rosane, Olivia. “Major Companies Join Call for Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium”. 2021. https://www.ecowatch.com/deep-sea-mining-moratorium-corporations-2651368554.html

26. “About The U.S. Extended Continental Shelf Project – United States Department Of State”. 2021. United States Department Of State. https://www.state.gov/about-the-u-s-extended-continental-shelf-project/.

Featured Image: ROV Deep Discoverer investigates a diverse deep sea coral habitat on Retriever Seamount. (NOAA photo)