By Richard Mosier

The concept for Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) is based on three bedrock tenets: the distributed force must be hard-to-find, hard-to-kill, and lethal. For decades, the Navy has been focused on and has continuously improved its fleet defense capabilities – the hard-to-kill tenet. And, with the recent increased emphasis on the offense, the Navy is making significant progress in becoming more lethal. In contrast, there is limited evidence of progress with respect to the hard-to-find tenet: the very lynchpin of the DMO concept, and the subject of this article.

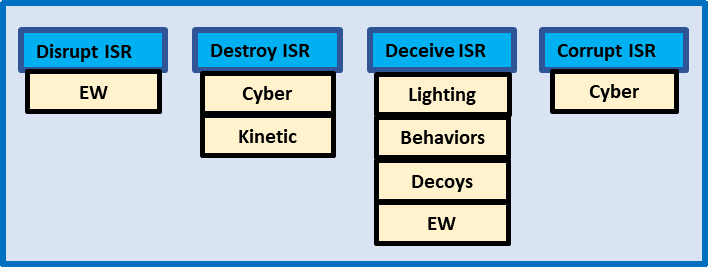

The hard-to-find tenet and the DMO concept itself are in response to Russia and China as recognized peer threats, including their advanced ISR capabilities to detect, locate, classify, and track (all elements of “find”) and target US maritime forces. When decomposed, the hard-to-find tenet requires consideration of a range of complex activities to disrupt, deny, deceive, corrupt, or destroy the adversary’s ISR ability to find the US force as outlined below.

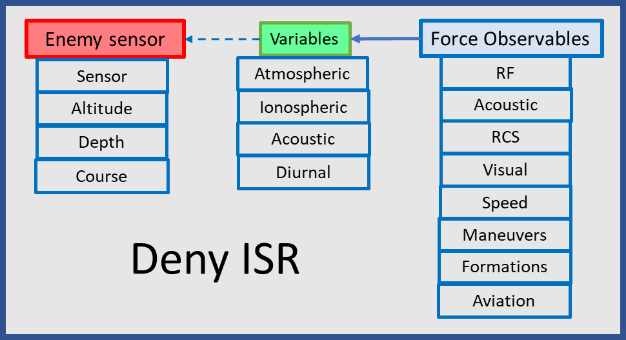

Deny ISR

This is perhaps the most complex but most effective way to be hard-to-find, track and target.

It involves five steps:

Step 1: Analyze the technical performance of enemy information systems. This level of technical analysis applies to each type of active and passive enemy ISR system that could be employed against distributed forces.

Step 2: Analyze and quantify the technical characteristics of US Navy force observables to include radars, line-of-sight communications, satellite uplinks, data links, navigation aids, and acoustic observables.

Step 3: Assess enemy ISR systems probability of detection of specific fleet systems’ observables at various ranges and altitudes, under various atmospheric, acoustic, and diurnal conditions.

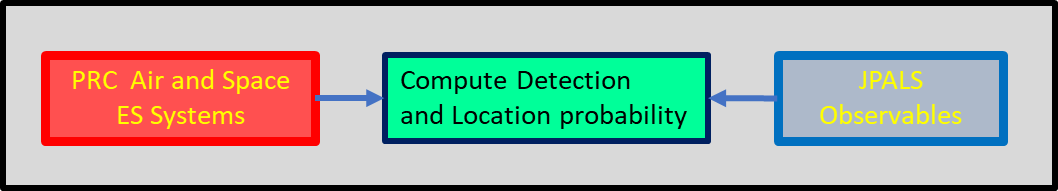

The Navy Joint Precision Approach and Landing System (JPALS) offers an example of such an assessment. JPALS is a GPS- and radio-based system to guide tactical aircraft to the carrier and through approach and landing on CVN/LHA/LHD ships in all weather and sea conditions.

Pilots returning to a carrier first engage with JPALS at about 200 nautical miles (nm), where they start receiving an encrypted, low probability of detection UHF broadcast that contains the ship’s position, allowing the aircraft to determine range and relative bearing to the ship. At 60 nm the aircraft automatically logs into JPALS via a two-way data link. At 10 nmthe aircraft start receiving precision data and the pilot follows visual cues to land.

The assessment would determine the probability of detection and location of the CVN/LHA/LHD transmitting the JPALS UHF broadcast by Chinese or Russian ISR aircraft and electronic surveillance satellites.

Step 4: Based on the results of step (3), develop and integrate into the combat system the aids to help the tactical commander manage force observables commensurate with the ISR threat to remain hard-to-find; and, to decide if and when it is tactically advantageous to transition from hard-to-find to hard-to-kill.

Step 5: Develop and continuously update a single, all source threat tactical ISR threat picture with the fidelity and timeliness to support the commanders’ ability to make better tactical decisions faster than the adversary.

DMO Force Combat Team

In addition to denying ISR, there are other methods for countering enemy ISR and keeping the force hard-to-find.

If, under the DMO concept, the force has to be ready to operate under mission orders, the combat team will have to be trained and ready to manage the all of the methods that can be used to remain hard-to-find. This will include the identification of the responsible positions on the team, their training, and the planning tools and decision aids they need for the planning and management of these methods for countering enemy ISR.

As with the well-established surface warfare mission areas of ASW, ASUW, and AAW, the tactical commander will require familiarity with and high confidence in the person managing the deny, disrupt, destroy, deceive, and corrupt ISR functions. This position will require an in-depth knowledge of collateral and SCI information sources and methods as well as offboard sensor coverage, tasking, and feedback mechanisms. The position will require in-depth knowledge of enemy ISR systems, their coverage, and, their performance attributes. It will require knowledge of ship/force sensing systems, their performance against various ISR threats, and the atmospheric and acoustic factors that affect their performance.

DMO Battlespace Awareness

Battlespace awareness1 is achieved by the continuous and rapid integration and presentation of relevant information, keeping the commander continuously updated so that he or she can make better and faster tactical decisions. The key factors in this process are relevance and timeliness. The current shipboard system architectures will require modifications to optimize the process for automated integration and presentation of relevant collateral and SCI information. Time is the key factor. An end-to- end analysis of the flow of information from receipt on ship to presentation to the commander would serve to identify and eliminate delays.

DMO force commanders should not only be cleared for access to compartmented information, as they are now, but they should also be educated on and comfortable with these off-board systems, their sources and methods, their strengths and weaknesses, and their tasking and mission plans. They also have to understand how own-ship and off board collateral and SCI information are integrated on the ship, in what space; managed by whom, and, in what form.

In summary, the hard-to-find tenet presents significant challenges that will have to be addressed, both in fleet operations and in Navy-wide efforts to man, train and equip the fleet with the capabilities for its’ successful execution. Two challenges stand out. The first is the determination of the OPNAV resources and requirement sponsor for the manning, training, and equipping the fleet for countering enemy ISR and managing the hard-to-find functions. The second will be adjustments in onboard architectures to assure each commander has the relevant information, in a consumable form and in time to make better decisions faster than the adversary. (A history of the Deny ISR task can be found in the detailed description of the US Navy’s Cold War efforts to be Hard-to-Find provided in Robert Angevine’s paper subject: “Hiding in Plain Sight—The U.S. Navy and Dispersed Operations under EMCON, 1956–1972.“)

The success of the Navy concept of Distributed Maritime Operations depends on being hard to find. This runs counter the JADC2 concept in which all DoD platforms, sensors, and weapons are networked, e.g. continuously transmitting and receiving information via line-of-sight, HF and satellite RF communications that unfortunately present the enemy with electronic surveillance observables that can be exploited to find and attack the transmitting ships. The Distributed forces can receive information via broadcast without compromising their presence. However, the decision regarding if and when to engage in RF communications for active participation in networks will depend on the commander’s assessment of the risk of enemy exploitation of those emissions to locate the force.

Richard Mosier is a retired defense contractor systems engineer; Naval Flight Officer; OPNAV N2 civilian analyst; OSD SES 4 responsible for oversight of tactical intelligence systems and leadership of major defense analyses on UAVs, Signals Intelligence, and C4ISR.

1. Battlespace awareness is: “Knowledge and understanding of the operational area’s environment, factors, and conditions, to include the status of friendly and adversary forces, neutrals and noncombatants, weather and terrain, that enables timely, relevant, comprehensive, and accurate assessments, in order to successfully apply combat power, protect the force, and/ or complete the mission.” (JP 2-01)

Featured Image: JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM (Feb. 21, 2022) Zumwalt-class guided-missile destroyer USS Michael Monsoor (DDG 1001) gets underway in Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Feb. 21, 2022. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Isaak Martinez)