By Claude Berube

The Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization at first glance may not appear to have any relevance to the sea; however, it is indicative of how even domestic issues may have an impact on maritime operations. The ruling reinforces the reality that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can use the high seas to conduct activity or bring attention to their cause. For example, one physician has proposed “a floating abortion clinic in the Gulf of Mexico as a way to maintain access for people in southern states where abortion bans have been enacted.” It is not clear at this point what kind of ship would be used, but the concept is not a new one.

Women on Waves is proof of this concept. Founded by Dr. Rebecca Gomperts, Women on Waves used ships to provide abortions off the coasts of countries which had restrictive laws. Some of the operations included Ireland (2001) using the Dutch fishing vessel Aurora; Poland (2004) on the Langenort; Portugal on the Borndiep which also saw a response by the Portuguese Navy; and Spain (2008) on a sailboat as well as a later Trojan Horse operation in Smir, Morocco (2012), and Mexico in 2017.

On January 29, 2010, this author had the opportunity to interview Dr. Gomperts regarding Women on Waves for a set of profiles about how NGOs use the maritime environment. The following is a transcript of that interview that reveals some important points about changes in technology and the visual impact of maritime operations. Although conducted over ten years ago, the interview is relevant now more than ever. When applied to a post-Dobbs world, the following interview positions Women on Waves as a case study for how abortion services might be operationalized in maritime environments.

Claude Berube: When did you first think about using ships?

Rebecca Gomperts: I first thought of using the sea to provide services when I was a physician on a Greenpeace ship.

CB: What was the advantage of providing services on the sea rather than going to the border of a country to provide those services?

RG: Because it’s the Dutch law that applies in international waters, you can help women legally and safely.

CB: Was it also cheaper to do it, logistics-wise, to provide the ship rather than another country?

RG: Women do that all the time. Women travel. That’s why it’s one of the main social injustices because women who do not have the money cannot travel to other countries. The ship is a visual; it makes the problem visual. Women travelling to other countries, it’s often under the radar, they do it secretly, they suffer tremendously but it’s not public. With the ship we are making the problem that exists visible.

CB: Have you found that the countries visited, do they prevent you from going into the harbor or do they prevent women coming out to you?

RG: We have done four campaigns with the ships so far. It was only Portugal that sent warships to prevent our ship from entering. That was the only time a government tried to stop the ship from coming in.

CB: How did that happen? Did they contact you on bridge to bridge?

RG: The Minister of Defence contacted the captain of the ship through a fax. They said Women on Waves was a threat to national security and health and they were preventing the ship from entering national waters. We filed a court case against the Portuguese government because they did this and we won this through the European Court for Human Rights.

CB: How did you decide to use the types of ships you used for your campaigns? Is your decision on what types of ships centered around the A-Portable [an 8×20 foot container that serves as a mobile clinic aboard the ship] or are there other things in the decision-making process?

RG: We used the Mobile Treatment Room three times and the ships had to be proper to carry that – it’s basically a container and so the ships had to be outfitted for the Mobile Treatment Room. That was the size of the ship that was determined by the Mobile Treatment Room; however there have been a lot of developments recently especially concerning medical abortions – abortion with pills – it has been proven very safe to take outside the surgical theater. The last campaign we did which was in Spain we actually had a yacht and we worked with the local organization because the miscarriage happens back on shore so follow-up care was provided by us. So we used a yacht without the mobile treatment room. For us, that is a much better solution.

CB: Is that because it’s cheaper?

RG: It’s much easier for us because you don’t need big harbors so you’re more flexible.

CB: You lease the boats on a short-term basis?

RG: Yes.

CB: How did you identify the crew? Were they volunteers? Were they paid? Did you have to vet them for qualifications for seamanship, for example?

RG: It depended what ship we used. Two times we had a ship registered under the Dutch shipping certificate and all the crew had to have their certificates in order. Most of the crew volunteered. Some were reimbursed. The captain was reimbursed. They had to do extra training sometimes to update their certifications. On the other side, the yacht for example, there were just two crew and they had sailing experience – they had been sailing for thirty years. But that’s different than having a ship under a Dutch shipping inspection.

CB: Did you decide to use the Dutch flag because of the flexibility that offered?

RG: I’m Dutch so we knew the situation here. I think there might have been other countries where we could have registered the ship but it was much more complicated.

CB: When you’re ready to go into a country’s waters do you know ahead of time what you will do in the case of their navy or coast guard approaching you?

RG: It was a European ship so we have European protection, but we have lawyers always that work very closely with us but we never expected to have what happened in Portugal. That’s why we have a group of lawyers standing by in case of such a situation.

CB: You’ve done four voyages in the past ten years; do you have any plans for the future?

RG: Yes. It’s a complicated thing to prepare. We only go to countries where we are invited by local women’s organizations and it’s like a year-long preparation with mobilizing on the ground because they’re the ones who know we’re there to support them in the legalization of abortion in their country.

CB: So your organization is more grassroots and you will wait to be invited.

RG: Sometimes we will meet to decide when the ship will come.

CB: What have you found to be the greatest logistical challenges to these voyages – that might be fuel, or food or water?

RG: Portugal was the most difficult but they can’t do that anymore because they lost the court case. The government fell and abortion was legalized. It was also the most effective campaign.

CB: Why was it the most effective, because it was the response of the Portuguese government that generated the most interest?

RG: Of course, that is absolutely the case. It was worldwide front page news. It was widely discussed in the European Parliament and basically it was considered a big scandal.

CB: You saw a lot of political changes immediately?

RG: Yes. It was one of the main issues in the campaign. So it brought a lot of interest especially because of the Minister of Defence.

CB: If the Portuguese government and the Minister of Defence had not done that, do you think it would have been as successful?

RG: No. But we were there to help women and a lot of women in distress who were calling.

What did that interview and subsequent research suggest? First, NGOs evolve based on changing technology. While Women on Waves originally used a larger vessel to transport the mobile clinic, abortion pills later allowed them to use sailing vessels which could enter more ports as well as smaller ones, therefore reaching a larger target audience. In 2015, the organization started using drones to deliver abortion pills in Poland and the following year in Ireland.

Second, the use of yachts instead of the larger vessels meant that the NGO did not require licensed ship captains and had more flexibility as well as reduced costs to the maritime operation. Third, and perhaps most important, was the term Dr. Gomperts used: “the ship is the visual.” This characterization is similar to how other NGOs use ships to garner media attention to their cause in a way that is not conveyed via a land-based operation. While the post-Dobbs concept of using vessels to provide abortion services in the Gulf of Mexico is still early in how it will be applied, the case of Women on Waves may be one way of understanding how it might occur and evolve.

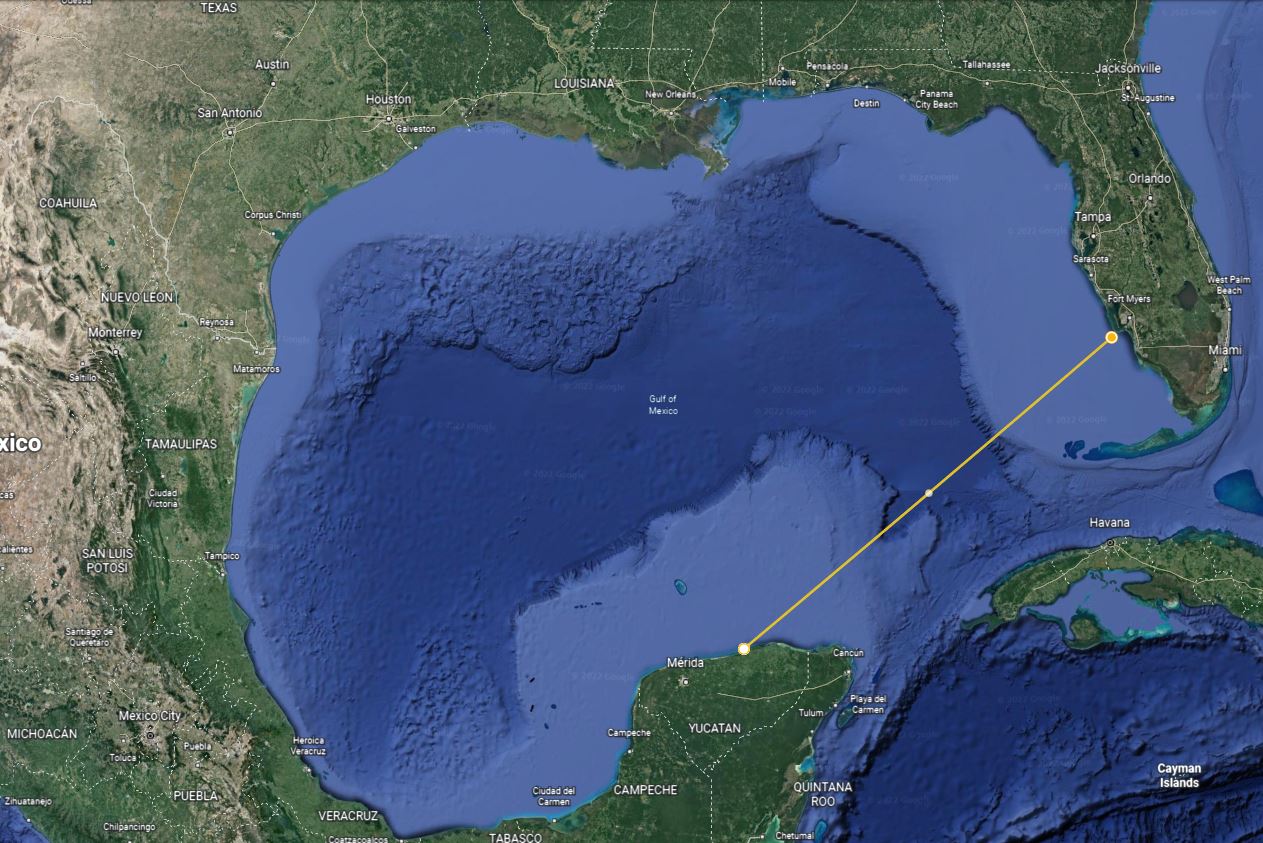

Finally, there is the perennial challenge of logistics. Assuming the organization does not use a sufficiently-sized sailing vessel, fuel consumption for a ship like an offshore supply vessel on which the organization could mount an A-portable would be problematic. Where, for example, would it refuel in the Gulf of Mexico? Assuming abortion services would be intended for states that would likely have more restrictive environments, the Gulf of Mexico – Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida – might find ways to impede a vessel from entering or exiting a port. The distance from the Texas-Mexico border to the west coast of Florida is approximately 850 nautical miles (nm). This suggests the vessel would require support from nearby countries like Mexico, Cuba, Belize, or Cuba depending on the fuel consumption and range of the vessel.

While the latter two would encounter various restrictions, Mexico legalized abortion in 2021, but Mexican states can provide their own levels of legislation. The Mexican state of Tamaulipas is the most geographically proximate state to American Gulf states but abortion there is illegal with exception for rape, maternal life, health, and/or if abortion were accidental. The Mexican state of Yucatan is approximately 450nm from the coast of Florida. Abortion is also illegal there with exceptions for rape, maternal life, fetal defects, economic factors, or if abortion were accidental.

As Dr. Gomperts said, the ship is the visual. Now, over a decade later, her words in a post-Dobbs world carry a different weight, one that Women on Waves has known for some time. The question now is how that visual might take shape and play out when the arena is Dobbs v. the ocean.

Claude Berube, PhD has taught at the US Naval Academy since 2005 and worked on Capitol Hill for two Senators and a House member. He is a Commander in the US Navy Reserve. He was the co-editor of Maritime Private Security: Market Responses to Piracy, Terrorism and Waterborne Security Risks in the 21st Century (Routledge, 2012). His next novel, The Philippine Pact, will be released in early 2023. The views expressed are his own and not of any organization with which he is affiliated.

Featured image: A Women on Waves ship near Morocco (Credit: Paul Schemm).