Russia-Ukraine Topic Week

By David Scott

Context

Currently, much of the attention given to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is focused on the land and air domains; but the Russian Federation Navy has also played a role in the Black Sea, where there has been some involvement by elements of Russia’s Pacific Fleet. Firstly, Russia dispatched a task force from Vladivostok comprising the Pacific Fleet’s flag ship cruiser Varyag, the anti-submarine destroyer Admiral Tributs, and the sea tanker Boris Butoma. These ships moved across the Indian Ocean to the Eastern Mediterranean for an inter-navy exercise in mid-February with six other ships from the Northern and Baltic Fleets, which were then dispatched to the Black Sea for amphibious operations against Ukraine. The Varyag flotilla remained in the Mediterranean, in effect complicating any easy NATO deployment to the Black Sea. Secondly, in mid-March, Russia dispatched their entire amphibious capabilities from the Pacific Fleet (the Oslyabya, Admiral Nevelskoy, Peresvet, and Nikolay Vilkov), amid speculation that they were on a three week voyage across the Indian Ocean carrying military trucks and other supplies to bolster Russian forces in the Ukraine. Thirdly, also in mid-March, news emerged that Russia was transferring by rail the 40th Krasnodar-Harbin Naval Infantry Brigade, based at Petropavlovsk in Kamchatka, and the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade, based in Vladivostok, for amphibious operations in the Black Sea.

In light of these contributions from Russia’s Pacific Fleet and the longer-term geopolitical and geo-economic significance of the region, this article looks at Russia’s maritime doctrine, assets, basing facilities, deployments, and relationships in the Indo-Pacific.

Maritime Doctrine

Russian aspirations were codified in the 2015 Maritime Doctrine, which focuses on the “waters of the World Ocean (mirovoy okean).” It pinpointed Russian “regional priority areas” as the Atlantic (including the Baltic, Black Sea and Mediterranean), Arctic, Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Antarctica.

Salient points for the Pacific Ocean Regional Priority Area included:

- “The significance of the Pacific Ocean regional priority area for the Russian Federation is enormous and continues to grow” (Point 62).

- “The Russian Far East has colossal resources, especially in the exclusive economic zone and on the continental shelf” (Point 62).

- “Development of capabilities (troops) and the military base installation system of the Pacific Fleet” (Point 65b).

- “An important component of the National Maritime Policy in the Pacific Ocean regional area is the development of friendly relations with China” (Point-63).

In comparison to the 2001 Maritime Doctrine, new features in 2015 were the shift from “Pacific Coast” to “Pacific Ocean,” the identification of military base installations for the Pacific Fleet, and the recognition of strategic partnership with China.

Salient points for the Indian Ocean Regional Priority Area included:

- “Development of friendly relations with India is the most important goal of the National Maritime Policy in the Indian Ocean region” (Point 68).

- “Periodically or as necessary, ensuring the naval presence of the Russian Federation in the Indian Ocean” (Point 69b).

In comparison to the 2001 Maritime Doctrine, a new feature in 2015 was the recognition of strategic partnership with India in the Indian Ocean.

Within the 2015 Maritime Doctrine, how do the two sections on the Pacific and Indian Ocean compare? Firstly, the Pacific had 80 lines devoted to it, while the Indian Ocean had a more modest 13 lines. Secondly, as in 2001, the Pacific, but not the Indian Ocean, was identified in terms of importance as already “enormous” and envisaged to “grow” still more. Thirdly, Pacific Fleet capabilities were identified as needing quantitative and qualitative growth. Fourthly, the Pacific Ocean Regional Priority Area included the eastern part of the Arctic within the Northern Sea Route. The 2015 Maritime Doctrine envisaged strengthening facilities on the Russian coastline and islands along the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk; however, Russia’s presence in the Indian Ocean was envisaged as being through “periodic naval deployments.” Politically, whereas cooperation with India was the “most important goal” for Russia in the Indian Ocean, friendly relations with China was the “important component” for Russian maritime policy in the Pacific. This ignores Russia’s dilemma of growing China-India competition and friction in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.

Basing facilities

Russia’s Pacific Fleet is headquartered at Vladivostok (“Lord of the East”) in a new military complex around Vladivostok Bay at the off-limits city of Fokino. Northward along the coast is the Sovetskaya Gavan base, after which the coast runs past the Russian island of Sakhalin and curves around the Sea of Okhotsk, which is enclosed by Russian control of the Kamchatka peninsula and the Kurile Islands. At Komsomolsk-on-Amur, the Amur Shipyard has recovered its earlier Soviet significance as the main shipbuilding enterprise for the Pacific Fleet.

Significant Russian forces are in Kamchatka, by Petropavlovsk, at the Rybachiy Nuclear Submarine Base, which was upgraded in 2015 to house the new Project 955 Borei-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile (SSBN) submarines. Russian submarine concentration in the Sea of Okhotsk reflects a deliberate bastion approach. Russia can further enclose the Sea of Okhotsk by securing the Kurile chain, which runs from Kamchatka to Hokkaido. At the northern end of the chain, K-300P “Bastion-P” mobile defense missile units with Onyx anti-ship missiles were placed on Matua in December 2021. At the south end of the chain, S-300V4 missile systems were placed on Iturup in December 2020, while high performance S-300V4 surface-to- air missile tests from Etorofu Island in March 2022 were taken as a signal against the United States and Japan. Investigations have been made for a further base for the Pacific Fleet in the Kurile Islands, with immediate access to the deep waters of the North-West Pacific. Japan’s support of sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine War has led to increased Russian military action in the Kurile chain, Russia’s “front line in the East.”

Outside of its own waters, Russia was given increased access to Cam Rahn Bay (Vietnam) in 2014, but not its old Soviet-era basing rights. In the Indian Ocean, however, Russia has established closer links with Myanmar and its military leadership, with naval cooperation as part of the wider military cooperation agreement signed in 2016 and further agreement in January 2018 for entry of Russian warships into Myanmar’s ports. The desirability of a Reciprocal Logistical Support (RELOS) agreement was mooted in the Russia-India annual summit Joint Statement in December 2021. Such an agreement would open up Russian access to Indian bases around the Bay of Bengal, including the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Having lost its Soviet-era bases in Somalia, Yemen, and Ethiopia, Russia has regained some presence in the Red Sea through the announcement in November 2020 of an agreement to build a logistical support and maintenance facility in the Sudan — an evident power play supporting Russian operations in the Eastern Mediterranean and establishing a gateway to the Western Indian Ocean. Following the military coup in October 2021, which was condemned in the West, the new Sudanese leader Abdel al-Burhan reaffirmed the general principles of this deal; as did the Deputy Head of State Mohamed Dagalo, who visited Moscow on February 24, the day that Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine.

Assets

As of 2022, the current Russian Pacific Fleet consists of 53 Warships — one guided missile cruiser, four large anti-submarine warfare (ASW) ships, two guided missile destroyers, four corvettes, eight small ASW ships, three guided missile corvettes, 11 guided missile boats, two seagoing minesweepers, eight base minesweepers, four landing ships, and five landing crafts — and 23 Submarines — four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, six nuclear-powered guided missile submarines, four nuclear-powered attack submarines, and nine attack submarines.

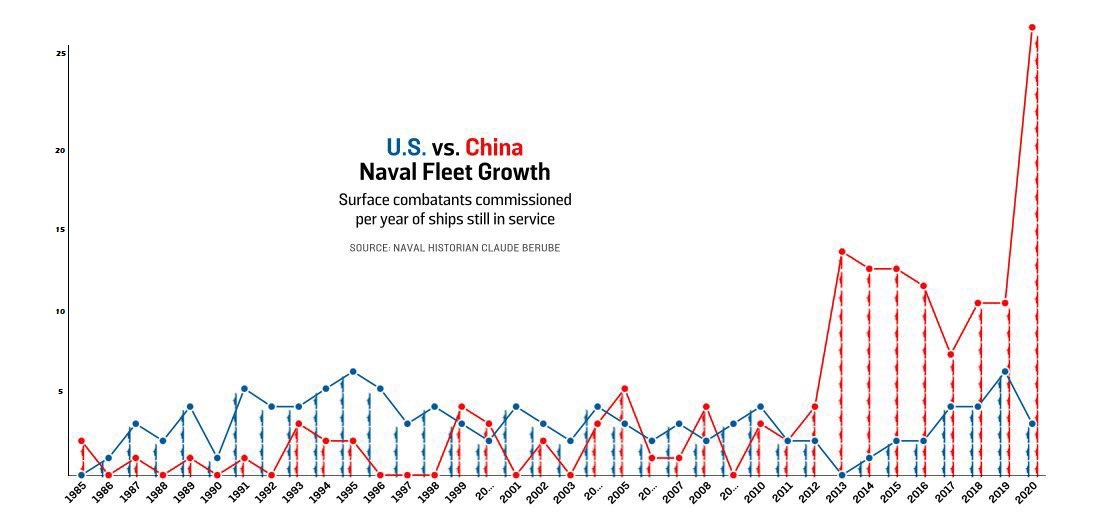

This is much smaller than the Soviet Pacific Fleet, and indeed the current U.S. Pacific Fleet of around 200 warships/submarines. Nevertheless, it represents some recovery from the troubled 1980s and 1990, during which rusting vessels (korabli ostoya “sediment ships”) were a common sight at Russian Pacific Fleet bases. Under Vladimir Putin, a “resurgence” of the Pacific Fleet by the late 2010s caused some unease for the United States, and talk by Russia of the Pacific Fleet’s “awe-inspiring sea power.” Plans for deployment of new large units to the Russian fleet were announced in the early 2010s, though the focus by 2020 changed to light units and submarines.

Various modernization and expansion programs are underway. Nanuchka-class corvettes (Project 1234) are having their Malakhit missiles replaced by Uran missiles. The Smerch finished this upgrade in October 2019 and has already rejoined the Pacific Fleet, with three other Pacific Fleet ships to be upgraded next. Udaloy-class anti-submarine destroyers (Project 1155) are being upgraded with Kalibr and Uran guided missiles. This upgrade commenced with the return of the Marshal Shasposhnikov to the Pacific Fleet in May 2021, with the Admiral Vinogradov next in line.

Nuclear powered Oscar-class cruise missile (SSGN) submarines (Project 949A) are being modernized, with their Granit missiles set for replacement by Kalibr missiles. The Irkutsk submarine leads the program, albeit slowly, to be returned to the Pacific by 2022/2023, followed by the Chelyabinsk. Finally, the Marshal Shasposhnikov and the Irkutsk are being provided with universal launchers for 3M22 Zirkon hypersonic weaponry. The Pacific Fleet is scheduled to get six improved Kilo-class diesel-electric attack submarines (Project 636.3) by 2024. The Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and the Volkhov already transited the Indian Ocean in October 2021. Next in line is the Magadan, commissioned in October 2021, and currently on its way to Vladivostok. The large Poseidon-class special purpose (Project 09852) nuclear submarine, complete with underwater nuclear drones, is scheduled for delivery to the Pacific Fleet by summer 2022.

Three new Gorshkov-class super frigates (Project 22350) are due to join the Pacific Fleet — the Admiral Amelko in 2023, and two others of that class by 2025. They are envisaged as leading powerful operational attack groups. Construction started for the Pacific Fleet in 2021 at the Amur Shipyard for four new corvettes of the Gremyashchy-class (Project 20385). They will join the Gremyashchy corvette, already envisaged by Vladimir as able to use hypersonic Zirkon missiles, which joined the Pacific Fleet in October 2021, to be followed by the Provorny. The Amur Shipyard has also been turning out Steregushchy-class (Project 20380) corvettes, all-purpose warships, including anti-submarine attack Ka-27 capabilities, for the Pacific Fleet. So far, they have produced the Sovershennyy in 2017, the Gromiky in 2018, and the Hero of the Russian Federation Aldar Tsdenzhapove in December 2020; the Rezkiy and Sharp are carrying out sea trials in 2022. Of significance, these corvettes have been augmented with anti-ship Uran-M missiles able to take out enemy destroyers.

Highlights in Pacific Fleet submarine augmentation were the arrivals of Project 955 Borei-class SSBN submarines — the Alexander Nevsky in 2015 and the Vladimir Monomakh in 2016. A flurry of submarine developments was announced in December 2021. Firstly, the Pacific Fleet received its first Project 885-M Yasen-class nuclear-powered cruise missile (SSGN) submarine, the Novosibirsk. Three more are envisaged for the Pacific Fleet — the Krasnoyarsk currently carrying out mooring trials, with the Perm and Vladivostokunder construction. Secondly, the advanced Borei-A SSBN submarine (Project 955A), the Knyaz Oleg, was commissioned for the Pacific Fleet. Both additions were welcomed by Putin in a video link. Thirdly, a second Borei-A class submarine, the Generalissimus Suvorov, was launched for service with the Pacific Fleet.

However, one weakness remains with the Pacific Fleet’s lack of air power. Russia’s only aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, remains attached to the Northern Fleet, leaving its Pacific Fleet without an aircraft carrier to face the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet, which has seven carriers.

Deployments

The Russian Federation Navy has been extending its radius deeper into the Pacific, and more widely, back into South-East Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Major war games (Ocean Shield 2020) were carried out in the Bering Sea in August 2020, the first since the Soviet period. This involved over 40 warships from the Pacific Fleet, including their flagship Varyag, as well as the surfacing by the nuclear attack submarine Omsk off the coast of Alaska. Anti-area access training was carried out at this choke point entrance to the Arctic, which is a growing focus for Russian Pacific Fleet submarines operating in the Northern Sea Route linking Asia and Europe.

In another clear signal to the United States, the Russian Navy conducted large scale exercises (up to 20 surface combatants, submarines, and support vessels, including again the Varyag), about 4,000 km into the “distant maritime zone” of the central Pacific, around 300 miles west of Hawaii. Creating some alarm bells for U.S. strategists, the Russian Ministry of Defense stated their practise purpose was destroying aircraft carrier strike groups.

Russia’s Pacific Fleet has been re-appearing in Southeast Asian waters, with an “uptick” in countries visited apparent since 2014. Russian naval activism was most recently reflected in the ARNEX exercise held with Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) states in the South China Sea in December 2021. Russia sent the anti-submarine destroyer the Admiral Panteleyev; “a rich dose of symbolism” but still “punching below its weight” (Storey).

Russian deployments to the Indian Ocean are multi-directional. At times, the Northern, Baltic, and Black Sea Fleets send vessels down from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. At other times, the Pacific Fleet deploys across the Indian Ocean. Reasons for deployment include joint exercising with India since 2003, anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden since 2008, and bilateral and trilateral exercising with Iran and China since 2019.

Pacific Fleet units have also been deployed further westwards up to the Mediterranean, an extension first witnessed in 2013 with the dispatch of a flotilla headed by the destroyer Admiral Pantaleyev, accompanied by two amphibious warfare ships, the Peresvet and Admiral Nevelskoi, and a tanker to join other ships from the Northern and Black Sea Fleets. This pattern of Pacific Fleet deployment from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean was repeated with the Varyag in 2016 and, currently, in 2022.

Relationships

In terms of exercising partners in the Indo-Pacific, Russia enjoys maritime cooperation with India, Iran, and China.

Renewing Soviet-era links, units from Russia’s Black Sea and Pacific Fleets commenced bi-annual Indra exercises with India in May 2003. These were carried out in the Bay of Bengal (2003, 2005, 2015, 2018), Arabian Sea (2003, 2009, 2019), Sea of Japan (2007, 2017), and Baltic Sea (2021). Nevertheless, some limitations remain. An Indian flotilla arriving at Vladivostok was unable to carry out the 2011 Indra exercise because the Pacific Fleet had no available ships. A Logistics Agreement for their two navies is close but was postponed at their December 2021 summit. The announcement from Russia in January 2022 that Indra naval exercises will be held in the Black Sea in Fall 2022 remains to be confirmed in light of drawn-out Russian operations against Ukraine in the Black Sea initiated in February 2022.

A naval cooperation agreement with Iran in August 2019 was followed by the Baltic Fleet dispatching the Yarolslav Mudry and the Elyna tanker for trilateral exercises with Iran and China in December 2019 — a format repeated in January 2022. Meanwhile, bilateral exercises with Iran were conducted in February 2021. The Baltic Fleet dispatched the corvette Stoyky and oil tanker Kola, and the Pacific Fleet dispatched the previously mentioned Varyag flotilla.

Significantly, Russia-China land cooperation in Eurasia is being matched by increasing maritime cooperation. The annual Joint Sea bilateral exercises initiated in 2012 have increased in complexity, interoperability, and range. These were carried out in the Yellow Sea in 2012 (and 2019), the Sea of Japan in 2013 (2015 and 2017), the East China Sea in 2014, and the Sea of Okhotsk in 2017. A particularly significant exercise was the extended operation between the Russian and Chinese navies in October 2021, which included sailing around the entire eastern coast of Japan. Russian naval exercising with China helps their respective spheres. Their joint exercises in the South China Sea in 2016 helped China; their joint exercising in the Mediterranean and Black Sea in 2015 and the Baltic Sea in 2017 helped Russia.

Russian naval exercises with China have also developed in the Indian Ocean, “teaming up on the US” (Siow; also Maestro). In November 2019, the Russian Northern Fleet dispatched its flag ship cruiser Marshall Ustinov and the tanker Vyaz’ma for trilateral exercises (Exercise Mosi) with China and South Africa. This was followed in late-December by the Baltic Fleet’s dispatch of the frigate Yarolslav Mudry and the tanker Elynafor trilateral exercises (Maritime Security Belt) with China and Iran in the Gulf of Oman, which were seen in China as pushing back against the United States. In January 2022, as mentioned, the Pacific Fleet sent the Varyag flotilla for trilateral naval exercises (Maritime Security Belt/CHIRU-2022) with China and Iran in the Gulf of Oman — a coalition which was described by Iran’s ambassador to Russia as creating “a lot of pain for the West.” Further bilateral exercises with China took place in the Arabian Sea (Peaceful Sea 2022) before the Russian flotilla continued to the Mediterranean to assist Russian operations in Ukraine.

Conclusions

Four points emerge. Firstly, while Russian strength in the Pacific shows renewal, it remains inferior to U.S. strength. Secondly, Russia’s close maritime cooperation with China is increasingly problematic for the United States, since Russia and China act as force multipliers for each other in the Indo-Pacific and beyond. Thirdly, Russian fleet activity in the Indo-Pacific is not just a question of Pacific Fleet deployment, but also involves inter-fleet deployments of the Northern, Baltic, and Black Sea Fleets to the Indian Ocean. Fourthly, this works the other way as well, with Pacific Fleet deployments going beyond the Indo-Pacific, not only to the Arctic, but also the Mediterranean, where inter-fleet exercises were carried out in 2013, 2016, and 2022. This may, however, be a sign of weakness, indicating the separate Russian Naval Commands do not have enough forces at their disposal.

Dr. David Scott is an associate member of the Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies. A prolific writer on Indo-Pacific maritime geopolitics, he can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

Featured image: Russian cruiser RFS Varyag, an Iranian frigate and Chinese Type 052D destroyer Urumqi in the Arabian Sea. (Credit: Navy Lookout)