By Dr. Ian Ralby

The recapture of the pirated Chinese fishing vessel Hai Lu Feng 11 on 16 May 2020 stands as one of the most successful recent examples of both maritime security cooperation and naval operations in the Gulf of Guinea. Pirates took the vessel and its crew of 11 on 14 May off of Côte d’Ivoire and sailed across the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of Ghana, Togo, and Benin before being interdicted 14 nautical miles off the coast of Nigeria. The information sharing across the region and the operations by the navies of Benin and Nigeria led to the successful release of the vessel and the hostages. The case will soon be the first true piracy case tried under Nigeria’s new Suppression of Piracy and Other Maritime Offenses Act.

Any deterrent effect from these successes, however, was not evident a month later when on 24 June 2020 the F/V Panofi Frontier, a Ghanaian-flagged vessel, was pirated off Benin with six crew members—one Ghanaian and five South Korean—taken hostage. The South Korean government, along with the vessel’s owner—a South Korean company—and the Ghanaian government, were involved in securing the release of the hostages, all of whom were freed by the end of July.

Much could be said about these two piracy incidents and what has happened since, but examining what each vessel was doing before it was attacked provides a new and important angle of insight into the region’s maritime space, all of which point to a need to rethink maritime domain awareness in the region. Civilian vessels not only avoid monitoring by turning off tracking devices, they engage in a variety of illegal practices to obscure their identity.

Sharing identities with other vessels, and engaging in corporate schemes to allow foreign companies to operate as domestic entities blur the already murky picture of maritime operations in the region. Regional governments need to take a new approach to maritime domain awareness, not only to better address illegality of all sorts, but to respond to emergency situations like pirate attacks. That approach has to include a mix of tools and techniques, including leveraging technology, conducting analysis, improving legal awareness and reforming laws, establishing processes and procedures for effective response, and, ultimately, building trust through an honest confrontation with what is really happening in the waters of West and Central Africa.

Insights from the Hai Lu Feng 11

Algorithmic analysis by Windward, a predictive maritime intelligence platform, of all the vessels transmitting Automated Information System (AIS) in the EEZs of the coastal states of the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS) indicates that between 1 September 2019 and 1 September 2020, a total of 527 vessels engaged in fishing operations. The Hai Lu Feng 11 is equipped with an AIS transponder, and was fishing on 14 May when it was pirated. Surprisingly, however, it does not appear on the list of 527 transmitting vessels.

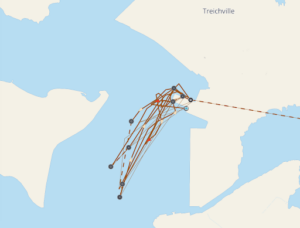

The Hai Lu Feng 11 was pirated outside the territorial sea of Côte d’Ivoire, but oddly, the following image captures the entirety of the traceable movements of the vessel over the eleven-month period after it arrived in Côte d’Ivoire for the first time on 30 October 2019:

Therefore, while the Hai Lu Feng 11 was the victim of piracy, it had also not followed the requirements of the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention to maintain its AIS turned on. Why was the Hai Lu Feng 11 operating dark other than when it was in the lagoon area around the port of Abidjan? How can the region improve its maritime domain awareness if both victims and perpetrators operate in the dark? And what else might be going unnoticed off the coast of Atlantic Africa? While a comprehensive answer to those questions would likely consume several volumes, a few interesting patterns arise in analyzing AIS data that may help give some answers.

Double Trouble

A substantial number of the vessels that fished in the ECOWAS region between September 2019 and September 2020 were sharing something they should not have. Twenty-seven vessels shared thirteen vessel names. In one case, three different fishing vessels, all flagged in the Gambia, and all using the same Mobile Maritime Service Identity (MMSI) number, used the name The Gambia 4. The full list is as follows:

| Name | Flag | |

| 1 | Dak940 | Senegal |

| 2 | Dak940 | Senegal |

| 3 | Fu Hai Yu 5555 | China |

| 4 | Fu Hai Yu 5555 | China |

| 5 | Fu Yuan Yu 381 | China |

| 6 | Fu Yuan Yu 381 | China |

| 7 | Guo Ji | China |

| 8 | Guo Ji | China |

| 9 | Han Sen 5 | The Gambia |

| 10 | Han Sen 5 | The Gambia |

| 11 | Long Tai 1 | China |

| 12 | Long Tai 1 | Ghana |

| 13 | Long Xing 622 | China |

| 14 | Long Xing 622 | China |

| 15 | Lu Qing Yuan Yu 051 | China |

| 16 | Lu Qing Yuan Yu 051 | China |

| 17 | Lu Yuan Kai Yuan Yu 877 | China |

| 18 | Lu Yuan Kai Yuan Yu 877 | China |

| 19 | The Gambia 4 | The Gambia |

| 20 | The Gambia 4 | The Gambia |

| 21 | The Gambia 4 | The Gambia |

| 22 | Wang 6 | The Gambia |

| 23 | Wang 6 | The Gambia |

| 24 | Yi Fen 26 | China |

| 25 | Yi Fen 26 | China |

| 26 | Yi Feng 30 | China |

| 27 | Yi Feng 30 | China |

Chart by the author using Windward data to indicate the vessels with identical names fishing in the ECOWAS region between 1 September 2019 and 1 September 2020.

While it would be bad enough that these vessels were sharing names, often under the same flag, they also sometimes shared International Maritime Organization (IMO) numbers and MMSI numbers, each of which is legally required to be distinct. Even vessels that did not share names may have shared these other identifiers. Excluding the vessels that had unknown IMO numbers, the following vessels shared IMO numbers:

| Name | Flag | |

| 1 | Long Tai 1 | China |

| 2 | Long Tai 1 | Ghana |

| 3 | Lu Qing Yuan Yu 057 | China |

| 4 | Lu Qing Yuan Yu 051 | China |

Chart by the author using Windward data to indicate the vessels with identical IMO numbers fishing in the ECOWAS region between 1 September 2019 and 1 September 2020.

What is most interesting here is not that the two Long Tai 1 vessels overlap from the first list, but that another vessel also used the same name as the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 051, even while this one was sharing an IMO number with the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 057. In other words the two Lu Qing Yuan Yu 051 vessels and the Lu Qing Yuan Yu 057 were in a strange triangle, each sharing something of the other.

When it comes to MMSI numbers another challenge arises—a number of the vessels that shared MMSIs with other vessels do not have clear names. Beyond the vessels in these last two charts, there are a few others that only share MMSI numbers, but the picture is messy and confusing to say the least. Given that the aim of all these identifiers is to have unique profiles for each vessel, this is a problem regardless of the other activities in which the vessels engage. The region cannot effectively govern its maritime space without addressing this issue, as there is no way to gain clarity amid the resulting confusion.

This creates serious concerns for security and governance as well. If several vessels have the same name, perhaps only one may get a license. So, for example, if The Gambia 4 has a license to fish, there is no reason law enforcement would stop The Gambia 4 from fishing. But three vessels may be fishing under that same name and thus that same license, meaning that they are getting three for the price of one and could be tripling their quota in turn. Equally, the implications for interdicting vessels suspected of other crimes, like trafficking, are quite challenging if there are no clear indicators of which vessel is which. This is a law enforcement nightmare, as the welter of matching names, IMO numbers, and MMSI numbers makes it hard to conclusively identify a vessel without there being some doubt.

Mirror Meetings

The presence of so many vessels with overlapping identities in the region is made more complicated by the fact that they also have a tendency to meet with each other or with vessels of nearly identical names. For example, in the period between September 2019 and September 2020 the following vessels met:

- Hai Lu Feng 9 and Hai Lu Feng in Côte d’Ivoire

- Long Tai 1 (China) and Long Tai 1 (Ghana) in Ghana

- Hai Lu Feng 1 (China) and Hai Lu Feng 5 (Ghana) in Ghana

- Hao Yuan Yu 866 and Hao Yuan Yu 860 in Liberia

- Fu Hai Yu 333 and Fu Hai Yu 555 in Sierra Leone

These are just some of the meetings between mirrored or virtually mirrored vessels in that time period. The concern is that this can create challenges for and confusion among law enforcement and those monitoring the maritime space. For example, the Long Tai 1 from China could – hypothetically – enter Ghana’s EEZ with some sort of illicit good like drugs, meet with the Long Tai 1 from Ghana, and exchange the drugs for fish. The Ghanaian vessel could then fish some more and return unchecked, with a cargo of drugs as well as fish, while the Chinese Long Tai 1 could transship at sea, without anyone suspecting either “Long Tai 1” of anything. This dynamic requires new approaches to maritime domain awareness to ensure that coastal states can effectively monitor and then interdict illicit maritime activity.

Here, too, we see that the Hai Lu Feng name is not without murkiness. While it was the Hai Lu Feng 11 flying a Chinese flag, there are a variety of Hai Lu Feng vessels in the region. The vessels carrying that name include 1 (China – fishing), 2 (China – high speed craft), 2 (China – fishing), 4 (China – cargo), 5 (China – fishing), 5 (Ghana – fishing), 6 (China – tanker), 6 (China – unknown class), 6 (Ghana – fishing), 7 (China – fishing), 8 (China – fishing), 9 (China – fishing), 09 (China – fishing), 10 (China – fishing), 11 (China – fishing), 12 (China – fishing). Complicating matters further, the vessels are frequently renumbered such that the 5 becomes 6, 4 becomes 2, etc. The inclusion of the Ghana flag in the mix is noteworthy. As with the Long Tai 1, the ability of two vessels of the same name, but different flags, to meet and create confusion for anyone trying to understand vessel movements undercuts maritime domain awareness.

Dark Activity

Given that the Hai Lu Feng 11 was dark both when it was attacked and, evidently, during any fishing activities it conducted in the region, it is perhaps not surprising that other vessels fishing in the region have an unusually high propensity to spend time dark as well. Out of the previously mentioned 527 vessels, 396 of them—or 75%—spent time with AIS actively turned off while at sea during the period from 1 September 2019 to 1 September 2020. By contrast, the Pacific coast of South America in the same time period saw 870 vessels fish, with 437—less than half—having periods of dark activity.

This is not merely signal loss, and so it raises the question: why? Dark activity, while likely a violation of the SOLAS Convention’s requirement that AIS stay turned on, is not per se illegal. It is, however, a strong indicator of suspicious activity. And when it comes to fishing vessels, there are three main concerns: 1) engaging in illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing; 2) transshipping catch in furtherance of IUU fishing; or 3) engagement in fisheries crime. Analyzing the dark activity of these 396 vessels may be a useful exercise, but for the purpose of this analysis, the key to note is that there is a lot of activity in the region that the vessels do not want seen. Some of that may be for safety reasons – to avoid detection by pirates looking to attack vessels that cannot make a speedy retreat on account of fishing activities. Maritime domain awareness requires multiple data sources to gain a more complete picture, as AIS alone will not be sufficient.

Vessel Monitoring and the Pirate Attack

While the Hai Lu Feng 11 was dark when it was attacked, it was monitored on the Ivorian vessel monitoring system (VMS) used to keep track of fishing vessels in the country’s waters. However, the Fisheries Department of the Ministry of Animal and Fisheries Resources, not the Ivorian Navy, controls the VMS, so when the vessel was attacked, there was a delay before Fisheries clarified the anomaly to the Navy. The lack of a common operating picture at the national and regional levels remains a challenge, and while it could be overcome with efficient interagency communication, whole-of-government approaches to maritime governance are always challenging. In the case of the Hai Lu Feng 11, rapid notification by Chinese officials to the various states along the coast helped make the regional approach effective. This is an important takeaway for how to bypass other maritime domain awareness deficiencies, particularly at the multinational level.

Insights from the Panofi Frontier

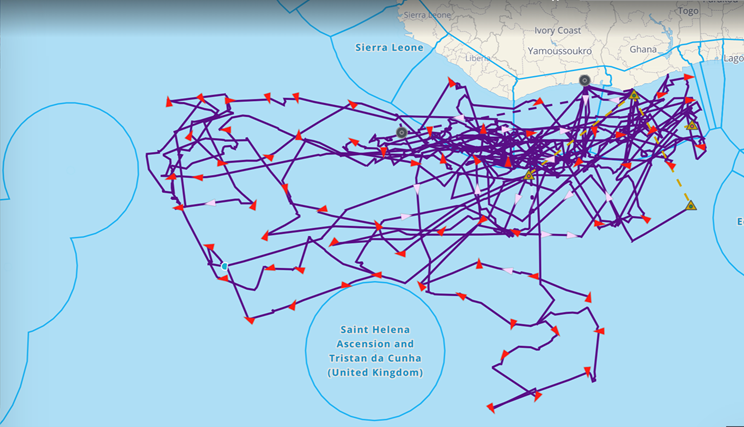

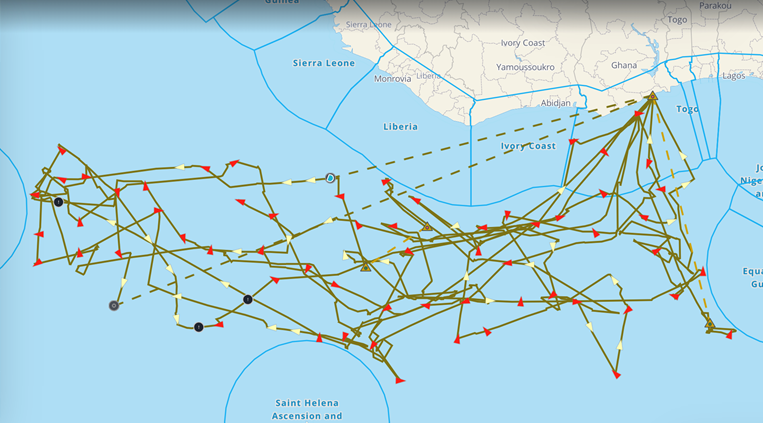

While the case of the Hai Lu Feng 11 was itself not terribly revealing, the absence of a history encouraged a deep dive into the more general nature of fishing vessel activity in the region. The Panofi Frontier, by contrast, reveals a movement pattern that has not received much attention in the region. Prior to being attacked, and again since, it has been engaged in a pattern of activity that moves not only laterally between different regional states, but across the Atlantic to the outer edge of the Brazilian EEZ. What is interesting, however, is that it is not alone. The whole fleet of “Panofi” vessels make similar journeys. Those vessels are all Ghana flagged and owned by a Ghanaian company. That company, Panofi Co., Ltd. in Tema, Ghana, is in turn owned by Silla Company of South Korea. In looking at the vessels’ paths, the similarity is unmistakable, particularly as most Ghana-flagged fishing vessels stay in Ghana or along the West African coast. For example:

The vessel tracks for the Panofi Path Finder, the Panofi Commander, the Panofi Fore Runner, and the Panofi Volunteer all look similar as well. While it makes sense that these vessels, all owned by the same company in Ghana and with the same beneficial owner in South Korea, might engage in a similar path, they are not the only ones. In fact, the Ghanaian Long Tai 1 discussed above follows a similar path:

But so does the Chinese Long Tai 1:

Interestingly, other vessels owned and flagged in Ghana, but with Asian beneficial owners, also engage in similar patterns of activity; examples include the Atlantic Queen, the Agnes 1, and the Africa Star. At the same time, however, other flags from other parts of the world may also be used by companies related to these vessels. The Atlantic Glory and Atlantic Prince, for example, are both Belize flagged, but engage in similar routes. Both the Liberty Grace and the Liberty Queen are flagged in Liberia and owned by Asian-owned Liberian companies, yet they still conduct similar routes out of Ghana across to the edge of the Brazilian EEZ. For example:

Similarly, the Everrich 1 is flagged in Côte d’Ivoire, but operates out of Senegal, and also spends time in areas by the Brazilian EEZ, as well as parts of the Eastern Caribbean. The Gambian-flagged Sage also seems to use Senegal and Ghana as its landing points, only recently having started developing a presence in the region. And a number of vessels, based in Senegal, flying the Senegal flag, and having beneficial owners in Asia – including the Maximus, and the Diamalaye – all exhibit the same pattern.

By contrast to all of these Asian-owned vessels, most local vessels – even the biggest ones – rarely venture beyond the EEZ of African coastal states:

While none of the Asian-owned vessels is obviously – based on this information alone – engaged in illicit activity, it is important to know that these routes and patterns exist. It may simply be that the Asian companies are taking advantage of local basing and flagging to be able to fish in more abundant waters of the Atlantic high seas. Regional governments should be aware of this, however, as it may still impact the sustainability of the region’s fishery. Of interest to law enforcement however, and setting aside the prevalence of IUU fishing in Atlantic Africa, these vessels’ tracks raise concerns about opportunities for engagement in fisheries crime.

A recent spike in drug interdictions from South America indicates a growing transatlantic drug route from South America. Some of that is containerized, but fishing vessels are increasingly being used to move drugs worldwide. The regularity of the routes of these foreign-owned fishing vessels between West Africa and the Brazilian EEZ provide potential cover and opportunity for moving narcotics or other illicit goods into the Gulf of Guinea. At a minimum, therefore, the states of West Africa should be vigilant in monitoring these routes to ensure that the fishing vessels do not engage in fisheries crime, assisting cartels with trafficking drugs.

Lessons for Maritime Domain Awareness

Maritime domain awareness in Atlantic Africa is vital not only to helping stop piracy, but also to helping address other crimes and activities that degrade the environment and undermine the rule of law. This examination of just two vessels that were attacked by pirates in May and June 2020 revealed a wealth of insight into the movement and action of vessels in the region. As helpful as that is, this insight is limited. This maritime domain awareness now needs to be connected to maritime domain actors. If the people who have visibility on incidents are not looking into these patterns and questions on a regular basis, there is no hope of the region being able to take meaningful and timely action when an emergency, like a pirate attack, occurs. Atlantic Africa, therefore, needs to focus on developing five things simultaneously:

- Technology – Having access to the most comprehensive and advanced MDA platforms, like Windward, that focus on the full spectrum of illicit activity, not just one issue like transshipment or even just fishing.

- Analysis – The data from the technology platform is just data until it is interpreted by someone who understands it, and the human analytical capacity of the Maritime Operations Centers and Multinational Maritime Coordination Centers needs greater attention.

- Law – Something that is undesirable is not necessarily illegal. Something that is illegal is not necessarily actionable. Watchkeepers and operators need greater understanding not just of what is happening, but of what portion of it can be stopped legally. Arresting a vessel without the legal authority or jurisdiction to do so can actually embolden criminals.

- Processes – There needs to be a consistent, well-practiced approach to responding to all the different forms of crime. Part of that means that the shippers and fishers in the region need to know who to call to get an effective response. Regardless of how that process looks, it needs to work.

- Trust – Technology is only part of the answer. Processes are only part of the answer. People on the water – fishermen, shippers, port operators and even recreational sailors – all need to know not only who to contact; they need to be able to trust that they will get a meaningful response and, at a minimum, not become the target of punitive or illicit action. All maritime actors – navies, coast guards, police forces, fishers, the maritime industry, NGOs and beyond – need to build the trust-based relationships that give them the confidence to share information and request assistance.

Leveraging these two piracy incidents for insights shines a spotlight on a variety of needs and approaches to meeting them. Given how many other attacks have occurred in 2020 alone, further analysis of this variety could only prove beneficial.

Dr. Ian Ralby is a recognized expert in maritime law and security and serves as CEO of I.R. Consilium. He has worked on maritime security issues around the world, and has spent considerable time focused on and was previously based in the Caribbean. He spent four years as Adjunct Professor of Maritime Law and Security at the United States Department of Defense’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies, and three years as a Maritime Crime Expert for the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. I.R. Consilium is a family firm that specializes in maritime and resource security and focuses on problem-solving around the world.

Featured image: F/V Hai Lu Feng 11 at sea at the time of its re-capture by local authorities. (Image courtesy of Maritime Security Regional Coordination Centre for Western Africa (CRESMAO) and the Interregional Coordination Centre (ICC), https://icc-gog.org/.)