Notes to the New Administration Week

By Jason Lancaster

The Navy’s annual 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan should be replaced with a congressionally-appropriated fleet act. This act would fund the construction of the fleet the nation needs. Over the past 10 years of annual 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans the fleet has shrank, not grown. U.S. shipbuilders lack the capability to build the required ships because there is little consistency in U.S. warship procurement.

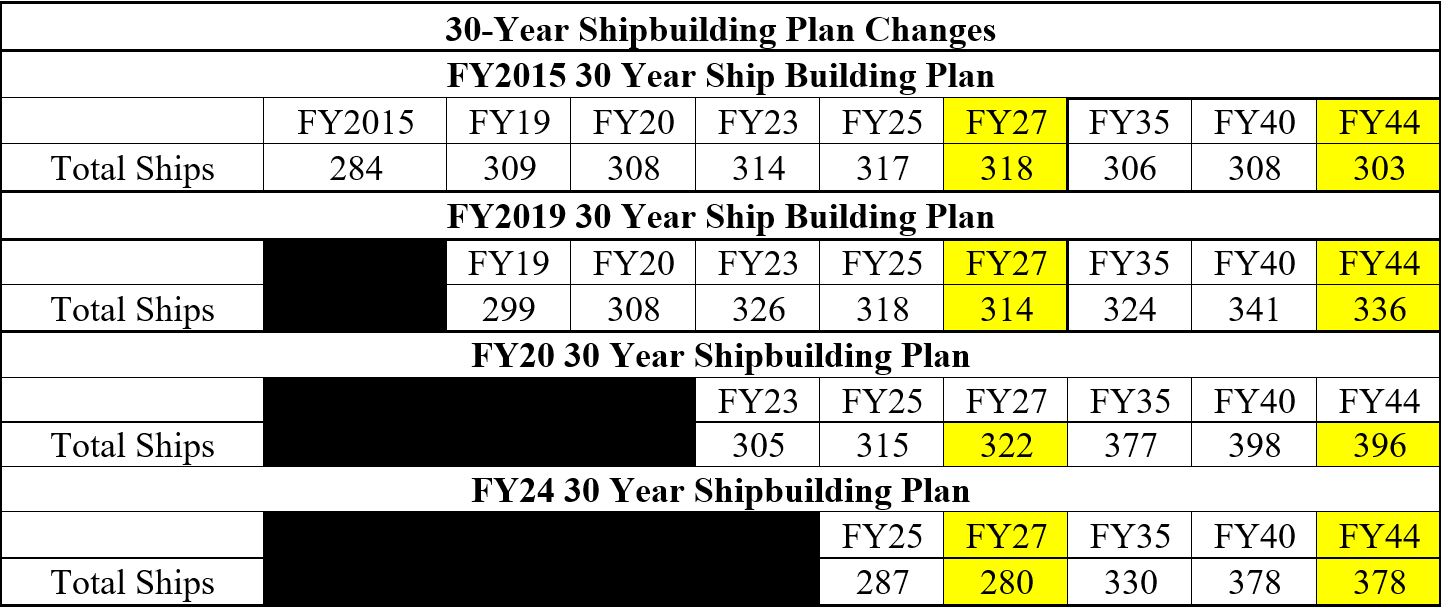

Annual budget changes destroy consistency in the annual 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan. The table below displays the ever-shrinking fleet. The fleet in fiscal year (FY) 27 and 44 are highlighted. FY44 was used instead of FY49 for consistency throughout the 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans.

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, the United States, Imperial Germany, and Austria–Hungary used fleet acts to fund desired force designs. Congress funded the Two-Ocean Navy Act in 1940 to expand the fleet by more than 70 percent. One would think that the imperial governments of Imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary would only have to persuade their Kaiser, but both nations’ Chiefs of Navy had to have their shipbuilding plans approved by their respective parliaments.

The Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940 provides a framework for a similar congressional act. In 1940, Congress authorized:

(a) Capital ships, 385,000 tons

(b) Aircraft carriers, 200,000 tons

(c) Cruisers, 420,000 thousand tons

(d) Destroyers, 250,000 tons

(e) Submarines, 70,000 tons

This act provided significant funding for ships, munitions, and shipyard expansions. It would help give the Navy a running start on wartime expansion by the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor more than a year later.

In Imperial Germany, Admiral Tirpitz proposed a fleet act that requested a Navy of a certain size. This plan assumed a replacement ship for each battleship after it reached 25 years of service life. Tirpitz’ Fleet Acts were passed in 1898, 1900, 1908, and 1912. Tirpitz’ Fleet Acts were based principally on assessments of the UK Royal Navy’s strength and requirements to defend overseas colonies.

Austria-Hungary had a similar system. After Italy began building battleships, Admiral Montecuccoli’s initial fleet plan was denied due to domestic politics. Admiral Montecuccoli eventually persuaded a shipyard to produce the first two ships. He secured a personal loan of 32 million Austrian Crowns to begin construction on the Viribis Unitis and Tegethoff while promising the government would procure the ships the following year.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy dealt with partisan politics. Montecuccoli was an expert at balancing political factions to accomplish his fleet plan. Czech delegates publicly voted against the Navy bill for partisan reasons, but privately supported it. The Czech company Skoda Works produced steel armor and battleship guns, offering well-paying jobs for Bohemia and Moravia, but the central government was antagonistic toward Czech independence.

Today, we have witnessed the Navy attempt to back out of block buys designed to reduce cost because annual DoD budgets did not support additional ships for the navy. A fleet act would provide the steady demand signal for ships that would enable companies to invest in required materials to sustain affordable shipbuilding for the long term.

It took decades for the Navy to reach this state. It will take steady and consistent funding to return the Navy to its desired size. A fleet act could provide a more viable mechanism for adjusting the Navy’s force structure and making a generational investment in naval power compared to the 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan, which has lost much of its usefulness.

Commander Jason Lancaster, USN, is a student at the National War College. He has served at sea in destroyers, amphibious ships, and a destroyer squadron. Ashore he has served as an instructor at the Surface Warfare Officers School, on the N5 at Commander, Naval Forces Korea, and in OPNAV N5.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official positions or opinions of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.

Featured Image: 1994 – A view of various ships under construction at the Ingalls Shipbuilding shipyard, Pascagoula, Mississippi. Front to back are the guided missile cruiser Port Royal (CG-73), the guided missile destroyer Stout (DDG-55) and the guided missile destroyer Mitscher (DDG-57). Inboard of Stout is the guided missile destroyer Ramage (DDG-61) and inboard of Mitscher is the guided missile destroyer Russell (DDG-59). (Photo via U.S. National Archives)

Outstanding idea…some kind of revamping of the current process needs to happening.

The cruiser Port Royal is now decommissioned. With her went many missiles. Almost all of the cruisers are mothballed or gone now. Most could still be active had a tenth of their replacement costs been spent on maintenance and updates.

China knows how many missiles a carrier strike group has. All they need is one more. Why make it easier?

Do they?

Does a Burke have 90-96 in the cells or the potential 360-384 with ESSM? Great reason to keep VLA and Tomahawk loads somewhere else.

Oh PULEEZE.

Unless the US allows SK and Japans shipyards to bid on new ships, expecting US yards to increase the fleet is a fools errand.

Let them bid on surface ships other than carriers and have them outfitted in the US.

This will create new US jobs, and these countries can ramp up to at least 10 to 15 new hulls a year.

Not changing the outdated law preventing this is just incredibly foolish and a continued danger to US security.

We could have corvette sized ships in numbers if we got serious.

The LSM test ship is being built in Indonesia.

It’s a good theory, and aligns with pure free-market idealism. However, those Korean and Japanese shipyards can be isolated, pressured, or directly targeted by the Chinese prior to or during a conflict. Ninety percent of the worlds ships are built within 1000nm of the Chinese coast, and a chip shot away from Chinese rocket forces. Ceding the remainder of shipbuilding to be under the gun doesn’t seem like it increases US security.

Perhaps the US should just build warships in Chinese yards, as it’s cheaper. What’s the worst that could happen?

Aside from needing to right our own shipbuilding industry, we also need to look past big and impressive and understand all our options. We are building a prototype LSM in Indonesia. Poland has plenty of shipbuilding muscle memory and would be a great way to solidify the strong relationship. Even Damen has the Galati Romanian yard to keep building at competitive cost.