Earlier this year, Britain marked the 70th Anniversary of the Battle of the Atlantic (BOA 70), to commemorate those sailors and airmen who lost their lives in serving and defending the vital trade routes into British ports throughout the Second World War. The Battle of the Atlantic was not a unique struggle; it was instead only the latest historical incident where an enemy of Britain had taken to the seas to harass British shipping with the aim of bringing the country under submission. The Germans had attempted it before in 1917, and the French numerous times throughout history, even developing an entire naval mindset around the idea, the Jeune E’cole. But as with many national commemorations, BOA 70, appears to have failed to engender a greater political and public understanding of the patent fact of Britain’s geo-strategic position as an island nation and the vulnerability inherent in such a position. Whilst reflection and contemplation on lives lost is apposite, it has a tendency to appeal to national sentiment and myth instead of to a rational appreciation of the historical lessons it can offer. One of the fundamental problems of our day is that the maritime realm resides on the fringes of the British psyche, resulting in a lack of awareness and understanding of the nation’s maritime heritage and continued reliance on the sea.

Britain is a ‘just enough, just in time’ economy. Around 90 – 95% of British economic activity is dependent of the sea. UK based shipping contributes £10bn to GDP and £3bn in tax revenues and is placed as the third largest service sector industry in Britain after tourism and finance. In 2011 the Centre for Economics and Business Research (Cebr) forecasted that the march of globalisation is forcing a dramatic rise in British dependence on maritime trade. British seaborne imports are projected, after adjustments for inflation, to grow 287% over the next two decades, and exports delivered increasing by 119%. The value of British imports in 2010 stood at £345bn and is expected to reach £1.95tn by 2030. In the same twenty-year period export values are expected to rise from £233bn to £1.63tn[1]. These figure are unsurprising as globalisation continues to drive up the level of international trade and sea transport remains the cheapest option for serving this trade. But what these figures do is underline the perennial fact that Britain remains heavily dependent on the sea for its prosperity and economic stability. However, perversely, the global commons lack the levels of policing required to guard against disruption to the global Sea Lines of Communication (SLoC)[2] which would inevitably have a palpable and dramatic impact on the daily life of British citizens; from the latest ‘Apple’ products not appearing on the shelves to more concerning shortages in food, gas and oil. But what is the likelihood of this? What actors would be in a position to be able to mount a credible threat to the free flow of goods around the globe.

The answer is, nobody can be sure. Nevertheless the possibilities are multifarious. Piracy, interstate confrontation, terrorism, civil war, resource competition, natural disasters, climate change and cyber warfare could all pose future risks to international shipping. The future is inherently unpredictable. Any suggestion in 2000 that NATO would be fighting a 12 year war in Afghanistan would have been dismissed as fanciful; 9/11 serves to demonstrate the destructive potentialities of terrorism; recent confrontations in the South China Sea reveal an interstate conflict which has taken on a distinctly maritime dimension and recent events in Egypt raise the threat to the free movement of international shipping through the Suez Canal. ‘Today, the assumption is that good order is a natural condition and can be taken for granted because ‘nothing happens’. But that ‘nothing happens’ is no accident, but is rather because of pre-emption and deterrence’[3]. This writer would strongly contend that the Royal Navy currently has insufficient numbers to deal with the low level threats posed by piracy and terrorism in addition to its other commitments. However the challenge is trying to convince taxpayers and the political establishment to make provisions for all eventualities, not just asymmetric. There is a tendency to assume that the interconnected nature of the international trade system means it is unlikely any nation state, with the capability to do so, would seriously consider disruption of the SLoCs or the key trading choke points as a way of advancing its national interests. Additionally, faith in international institutions and their role in diffusing crises is undermining public and political desire for increased expenditure on armed forces. Admiral Sir Jeremy Blackham and Gwyn Prins, writing in 2010 urged that ‘defenders of the status quo base their arguments on two strong assumptions. The first is that in a globalised and increasingly interdependent world, the powers of multilateral institutions and of supranational jurisdictions will and should wax, as those of the nation state wane. The second premise is that the utility of ‘hard power’ is being swiftly eclipsed by that of ‘soft power’, such as development aid. This stance has been given material expression in consistent year-on-year real money increases in the budget of the Department for International Development, at the expense of the chronic underfunding of the Ministry of Defence (MoD)’[4]. But as more nations with divergent national interests look to exploit the sea for their national advantage or to generate strategic leverage over regional rivals, the likelihood of confrontation can only increase. As Dr Lee Willett of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) wrote ‘[Globalisation] increases the perception of the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ and can fuel radicalisation and conflict, in particular with regard to resources such as energy, food and water. Globalisation also enhances the impact of events overseas on the UK’[5]. Should a crisis emerge where a state actor mounts a sustained and determined attack on the international trade routes, protracted procurement timelines would preclude any rapid generation of the forces required to counter such a threat.

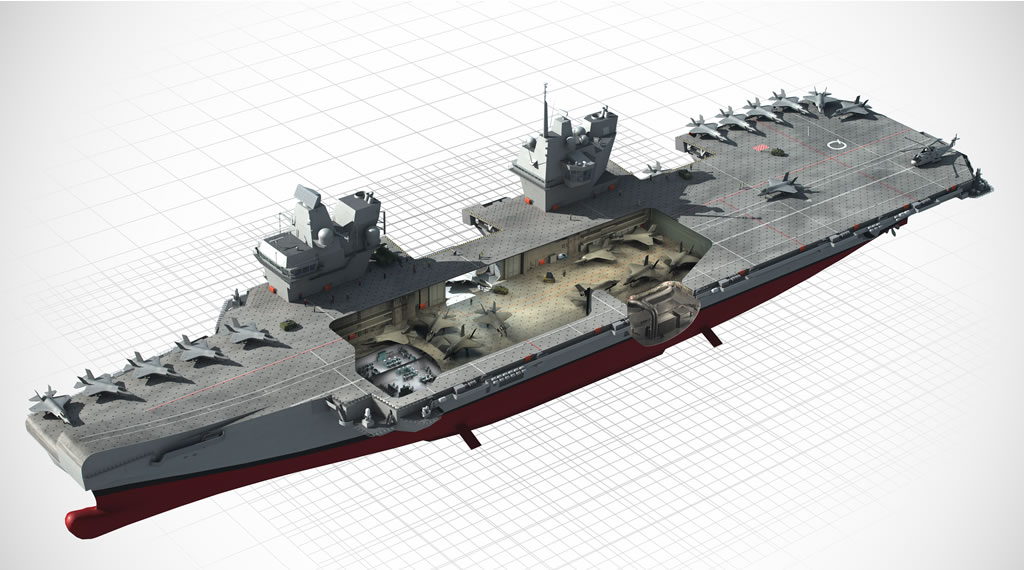

It is, or at least it should be, a simple assumption, that any government has a fundamental responsibility to take every possible action to protect its people from threats to their way of life, both through diplomatic means and military preparedness. In the case of Britain, maritime trade protection should be a key focus, or at the very least a constant consideration in defence planning, due to its critical contribution to the nation’s prosperity. The present size of the Royal Navy is dictated by current challenges as opposed to the full spectrum of future threats. The Royal Navy currently has 19 frigates and destroyers supporting a British commercial fleet of some 900 vessels. Once the new Aircraft Carriers are launched escort duties will further reduce the number of ships available for dedicated trade protection and counter-piracy operations[6]. The SDSR had promised catapults and arrestor gear for the new carriers to ensure interoperability and greater opportunity for the formation of Joint Maritime Task Groups that would ‘reduce the overall carrier protection requirements on the rest of the fleet’, freeing up RN vessels for trade protection[7] but a recent government u-turn means a reversion to the STOVL variant of the Joint Strike Fight and the abandonment of ‘cats and traps’ has inevitably made this more problematic. ‘Use of the sea demands presence along the sea routes. Presence is the prerequisite for the silent deterrent messages that naval force alone can articulate’[8] and a credible presence requires numbers and therefore greater investment in frigates and destroyers. It is mystifying that the Royal Navy is struggling to garner a greater share of the public purse, but a key reason for this is a lack of public appreciation of the increasing levels of maritime trade entering British ports delivering the goods, both vital and luxury, that they take for granted. A clearer definition of national strategy could clarify military force structures and diffuse tri-service infighting through sober appraisals of long-term national strategy, of which the Royal Navy, as the guardian of trade, is the key component.

In a recent article in the Naval Review entitled ‘Affordability in a Wider Context’, Paul Fegan investigated defence inflation and the impact this has had on the costs of warship procurement programmes. He concludes that, if this subject is examined through the lens of GDP as opposed to money spent in real terms, it is clear there has been ‘little change in the amount of national income needed to buy a new ship, even a ship which is technologically advanced and matched to contemporary threats…It is perhaps reassuring that we are asking no greater a national commitment to buying a warship than we were 50 years ago’[9]. One example he cites is that in cash terms HMS Daring (launched in 2006) cost 4,509 per cent more than HMS Devonshire (launched in 1960) yet the latter required 0.049 per cent of GDP against Daring’s 0.047. Paul Fegan rightly concludes that it is then not a question of defence inflation and the notion that we simply can’t afford to sustain a large fleet but it is instead an issue of priorities, and when it comes to prioritising those election-winning strategies, welfare and health among other immediacies will almost always trump defence. But it would seem appropriate to recognise that in order to sustain health and welfare, defence must deliver with respect to global trade protection and therefore should be treated as an equal partner rather than as an aged relation, no longer needed in this modern world. Such short-termism is dangerous and failing to acknowledge the prospective threats to shipping and taking measure to counter these threats, borders on the negligent.

Britain is an island. It is a Sea Power in the truest sense; its history and its future will be to a great extent shaped by its interaction with the world’s oceans. The sea has for centuries been a source of strength, providing her with a barrier against invasion and a source of economic prosperity and in so doing forging a resilient national character. However the sea, if under appreciated as a key strength has the potential to become a key vulnerability. The continued reduction in the Royal Navy’s size has, without doubt, dramatically hit its capability and flexibility. This has been the inevitable consequence of government policy, authored by policymakers with little grasp of strategy, more concerned with securing international kudos by focusing on high profile ‘kinetic’ conflicts as opposed to supporting the mundane but critical tasks performed by the Royal Navy on a daily basis. Having a flexible maritime force to counteract potential threats to international SLoCs, no matter how remote they may seem at the present time, is common sense for an island nation and a duty of its government. It must be cautioned that reliance on the support of other navies is a risky approach; any action has to assume political agreement and interoperability questions remain with regards to the new Royal Navy carriers after the removal of the proposed ‘cats and traps’. The decline of the Royal Navy, reflects political and other military priorities and from this we can only assume there is either ignorance as to the significance of the maritime trade sector or an arrogant disregard of the threats posed to it. The days of lobbying on behalf of the Royal Navy; ‘we want eight, we wont wait’, are regrettably long gone, and with the government’s short term horizon and a public ignorant of our maritime dependency there is a need for the key stakeholders both in the forces and in the maritime shipping and insurance industries, to work together to engender a greater understanding amongst the public and politicians.

It would not be an exaggeration to claim that Britain owes its existence, as a free and democratic nation, to its merchant marine and its Royal Navy, as the recent Battle of the Atlantic celebrations highlighted. But the memory of that struggle, if it is to have a lasting legacy, must be transposed into tangible lessons and sensible policy planning for the future. Britain’s strength derives from her island status, but it is this that is also her greatest weakness. She risks being hostage to events until there is a realisation in Whitehall that ships are relatively inexpensive and ignoring the threats to prosperity they guard against could come at an intolerable price.

Simon Williams received a BA Hons in Contemporary History from the University of Leicester in 2008. In early 2011 he was awarded an MA in War Studies from King’s College London. His postgraduate dissertation was entitled The Second Boer War 1899-1902: A Triumph of British Sea Power. He continues to write on naval history and strategy and in 2012 he hosted the Navy is the Nation Conference, in Portsmouth, UK. The aim of this event was to explore the impact of the Royal Navy on British culture and national identity. His second event on Navies and National Strategy is due to be held in early 2015.

2 thoughts on “Learning from History: British Global Trade and the Royal Navy”