From author Ian Birdwell comes The Changing Arctic, a new column that will focus on the unique security challenges presented by the increasingly permissive environment in the High North. The Changing Arctic will examine legal precedents, rival claimants, and possible resolutions for disputes among the Arctic nations, as well as the economic implications of accessing the region’s plentiful resources.

By Ian Birdwell

The Northwest Passage was once a mythic trade route that claimed dozens of Europe’s foremost explorers. Today, travelers can traverse the passage once sought by the likes of Cabot, Drake, and Franklin on the world’s first cruise line1 from New York to Anchorage; the trip lasts only about a month. This shift in accessibility to the Arctic is a direct result of the planet’s warming climate. While increased access to the Arctic offers advantages in terms of commerce and tourism, it has also ushered in a new era of maritime security issues for Arctic nations. Specifically, as the Arctic Ocean warms and northern ice sheets recede, the United States, Russia, Canada, Norway, and Denmark will confront new aspects of maritime security, potentially causing rifts in long-established relationships. As such, it will prove increasingly important to examine the history of these states’ interactions with an eye to the Arctic Ocean’s commercial future.

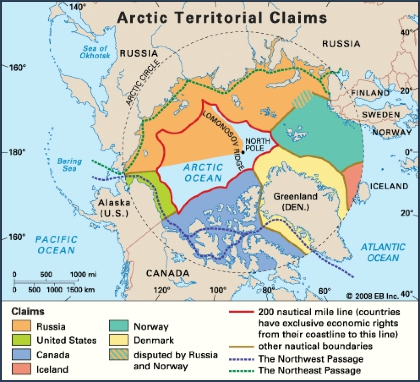

The Arctic has always been a place of contention for the nations surrounding it. As receding sea ice opens new sea routes, however, a comprehensive understanding of historical territorial disputes in the Arctic and the influence of the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) will be necessary. Canada was the first nation to claim vast swaths of territory in the Arctic Ocean in 1925. Not long after the Soviet Union followed suit, laying down their own claim in 1937.2 Though not yet passable by sea, control of Arctic territories was viewed as beneficial as it provided access to and providence over air routes. While moderately contested, Arctic territorial disputes would only become a marquee issue during the Cold War, when the region gained strategic significance as an area to base submarine-launched nuclear weapons.

Arctic nations’ ratification of UNCLOS and the end of the Cold War were catalysts for tension. Notably, the provisions of UNCLOS did not affect Arctic relations until climate change began in earnest because the majority of exclusive economic zones provided within it were practically inaccessible. However, as the ice has melted, the tenants of the Convention have failed to alleviate emerging territorial concerns. Four of the five Arctic Nations have only recently ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas3; the United States has still yet to do so.

As the waters warm, the Convention has been used as a tool to entrench territorial claims4 through UN appeals and report submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf UN Subcommittee (CLCS). In short, the interested parties are attempting to exploit the convention as a way to extend legitimate Arctic claims beyond the 200 nautical mile mark, as in Norway’s Submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). While Norway’s submission is noted by the UN is based on independent negotiations with other Arctic states to extend5 beyond the 200 nautical mile mark6, the most recent Canadian7, Russian, and Danish8 submissions to the CLCS have been partial submissions, allowing states to make arguments for territorial extensions in the Arctic beyond the CLCS time limit of ten years following ratification of UNCLOS, as outlined in article four9 of Annex II of the Commission of the Limits of the Continental Shelf section of UNCLOS. This, coupled with the geography of the Arctic Ocean, makes Arctic relations more difficult as it pushes territorial disputes into the realm of global bureaucracy under a convention poorly designed for use at the top of the world.

Every square kilometer of ice that disappears raises the stakes in the Arctic region due to its large untapped commercial potential and as the world’s next trade route. Ice previously made oil exploration infeasible. Now, a shrinking ice sheet makes it easier to maintain oil rigs while offering opportunities for expansion. Russia has been pushing the most for this kind of expansion10 due to their expansive arctic coastline. The Russian Federation stands to gain the most commercially. However, the opportunity to control vast amounts of petroleum resources has the United States, Canada, and Denmark excited for drilling opportunities as well. While the recent drop in oil prices11 has tempered this excitement somewhat, time will tell if market shifts and changes in government regulation spark an oil rush in the Arctic. This throws not just national oil giants like Gazprom into the Arctic, but potentially any private oil company capable of negotiating the use of ocean territory into the mix, further complicating territorial disputes and international agreements. Thus, it becomes vital for nations on the Arctic Ocean to solidify their territorial claims either in international courts, diplomatic agreements, or through deterring their rivals from contesting their claims with force.

Passage through the Arctic region12 is likely to become incredibly important as ice levels stabilize and charts improve, yet there are several rising complications for passage that are not environmental. While most routes pass through either Canadian or Russian territorial waters, the entrances to those routes can be militarily contested by Denmark, the United States, and Norway, regardless of which nation’s territorial claims include those waters. This in and of itself poses a problem, because some form of stability and control is needed to ensure shipping routes can be used. While it is unlikely for routes to be blockaded or military conflict to arise, the fact passage control could be contested by any of these nations forces them to develop Arctic-capable assets.13

As climate change alters the Arctic Ocean, the transformation of the world’s highest seas will push the nations surrounding it into an area of unresolved territorial disputes and increasingly higher financial stakes. To provide for more detailed analysis on these nations, the consecutive articles in this series will take an in-depth look at each nation’s goals, limitations, and security concerns as the ice sheets recede.

Ian Birdwell holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Government and International Politics from George Mason University.

1. Paris, Costas “Luxury Cruise to Conquer Northwest Passage” Wall Street Journal. May 10, 2016 <http://www.wsj.com/articles/luxury-cruise-to-conquer-northwest-passage-1462872605 >

2. McKItterick, T.E.M. “The Validity of Territorial and Other Claims in polar Regions” Journal of Comparative legislation and International Law, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1939)

3. United Nations “Declarations and Statements” Oceans and Law of the Sea. Accessed June 3, 2016 <http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm#Denmark Upon ratification>

4. Associated Press in Toronto “Canada to Claim North Pole as its own” The Guardian. December 9, 2013 <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/10/canada-north-pole-claim>

5. Russian Federation “Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf Outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines” United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. Updates June 30, 2009 <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_rus.htm>

6. Kingdom of Norway “Commission on the limits of the Continental Shelf Outer Limits of the contiental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines” United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. Updated August 20, 2009 <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_nor.htm>

7. Canada “Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf Outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines” United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. Updated December 29, 2014 <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_can_70_2013.htm>

8. Kingdom of Denmark “ Commission on the limits of the continental shelf outer limits of the conteitnal shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines” United Nations Oceans and Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. Updated May 21, 2014 <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_dnk_68_2013.htm>

9. United Nations “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Annex II” <http://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/documents/annex2.htm>

10. Gurzu, Anca “Economic pain pushes Russia to drill in high Arctic” Politico April 24, 2016 <http://www.politico.eu/article/economic-pain-pushes-russia-to-drill-in-high-arctic-oil-energy-natural-gas/>

11. Krauss, C. and Stanley Reed “Shell Exits Arctic as slump in oil prices forces industry to retrench” New York Times. September 28, 2015 <http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/29/business/international/royal-dutch-shell-alaska-oil-exploration-halt.html>

12. Stephens, Hugh “Northwest Passage a Key to Canada’s relationship with Asia” The Globe and Mail.May 19, 2016 <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/northwest-passage-a-key-to-canadas-relationship-with-asia/article30091202/>

13. Weber, Bob “Denmark joins Arctic arms race” The Toronto Star. July 26, 2009

Featured Image: Arctic waters (Incredible Arctic / Shutterstock)

Glad CIMSEC is looking at the Arctic more, but please don’t make this series a place for the fear-mongering that seems to pervade media and pundit coverage of the region. International relations are remarkably cooperative up north, and they will likely continue to be. Even as Russia rolled through Ukraine, things still remained cooperative in the Arctic. Just really think through the coming articles and look at the true literature on the region beyond simply overblown coverage from the uninformed that aims to get clicks.