The following article originally featured at the National Maritime Foundation and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Gurpreet S. Khurana

Since 2010, the concept of ‘Indo-Pacific’ has gained increasing prevalence in the geopolitical and strategic discourse, and is now being used increasingly by policy-makers, analysts and academics in Asia and beyond.1 It is now precisely a decade since the concept was proposed by the author in 2007. Although the Australians have been using the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ earlier, it was the first time, at least in recent decades, that the concept was formally introduced and explained in an academic paper. The said paper titled ‘Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation’ was published in the January 2007 edition of Strategic Analyses journal of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi.2

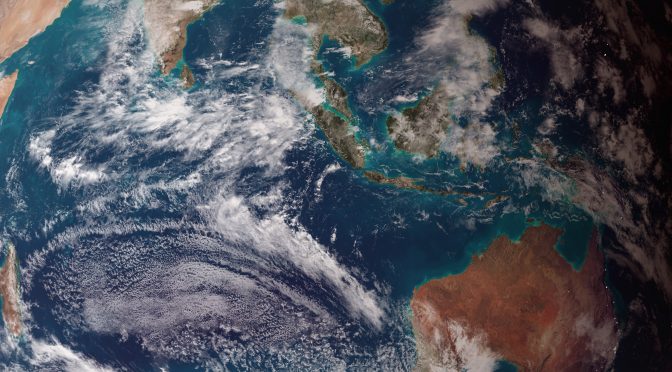

The term ‘Indo-Pacific’ combines the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and the Western Pacific Region (WP) – inclusive of the contiguous seas off East Asia and Southeast Asia – into a singular regional construct. There are some variations based on specific preferences of countries. For instance, the United States (U.S.) prefers to use the term ‘Indo-Asia-Pacific’, to encompass the entire swath of Indian and Pacific oceans, thereby enabling the U.S. inclusiveness for it to maintain its relevance as a resident power in this important region. Nonetheless, the fundamental ‘idea’ of ‘Indo-Pacific’ is accepted nearly universally. It has been argued that the concept of the Indo-Pacific may lead to a change in popular “mental maps” of how the world is understood in strategic terms.3

It may be conceded that there are some fundamental and distinct differences between the IOR and the WP in terms of geopolitics – including the geo-economics that shape geopolitics – and even the security environment. If so, how did the concept of ‘Indo-Pacific take root? It is a conceptual ‘aberration’? What was the underlying rationale behind the use of the term? This essay seeks to examine these pertinent issues. Furthermore, based on current trends, the analysis presents a prognosis on the future relevance of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept.

Indian Ocean-Western Pacific Divergences

Undeniably, the IOR and the WP differ substantially in nearly all aspects, ranging from the levels of economic development of countries and their social parameters, to the security environment. Unlike the IOR, the WP has been beset by major traditional (military) threats. Such insecurity is based on historical factors, mainly flowing from the adverse actions of dominant military powers, particularly since the advent of the 20th century – for instance, Japan; and now increasingly, China – resulting in heightened nationalism and an attempt to redraw sovereign boundaries, including ‘territorialization’ of the seas. The military dominance of these powers was a consequence of their economic progress, beginning with Japan, which later helped the other East Asian economies to grow through outsourcing of lower-end manufacturing industries – the so-called ‘Flying Geese Paradigm.’4

In contrast, the recent history of the IOR is not chequered by onslaught of any dominant and assertive local power. Why so? Despite being rich in natural resources – particularly hydrocarbons – the IOR countries were severely constrained to develop their economies. Not only did the colonial rule of western powers last longer in the IOR, but also these countries were too diverse in all aspects, and were never self-compelled to integrate themselves economically; and therefore, lagged behind East Asia substantially in terms of economic progress. As a result, many of these countries could not even acquire adequate capacity to govern and regulate human activity in their sovereign territories/maritime zones, let alone developing capabilities for military assertion against their neighbors. Therefore, the numerous maritime disputes in the IOR remain dormant, and have not yet translated into military insecurities. (The India-Pakistan contestation is among the rare exceptions, and is based on a very different causative factor.) The IOR is plagued more by non-traditional security issues, such as piracy, organized crime involving drugs and small-arms, illegal fishing, irregular migration, and human smuggling.

The Rationale

The broader rationale behind the prevalence of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept is the increasing developments in the area spanning the entire ‘maritime underbelly’ of Asia, ranging from the East African littoral to Northeast Asia. This is best exemplified by the launch of the U.S.-led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) in 2004 to counter the sea-borne proliferation of WMDs and their delivery systems. The PSI focused on the maritime swath stretching from Iran and Syria to North Korea.5 These developments led strategic analysts to search for a suitable common regional nomenclature to be able to communicate more effectively. The term ‘Asia’ was too broad and heterogeneous; and ‘continental’ rather than ‘maritime.’ The term ‘Asia-Pacific’ – which traditionally stood for ‘the Asian littoral of the Pacific Ocean’ – was inadequate.6 The ‘Indo-Pacific’ – shortened from ‘Indian Ocean–Pacific Ocean combine’ – seemed more appropriate.

The coinage of ‘Indo-Pacific’ has much to do with the increased eminence of India with the turn of the 21st century. It began in the 1990s with India’s impressive economic growth, and later, its nuclear weaponization. In 2006, Donald Berlin wrote that the ‘rise of India’ is itself a key factor in the increasing significance of the Indian Ocean.7 Also, India could no longer be excluded from any overarching reckoning in the Asia-Pacific; be it economic or security related. For example, India was an obvious choice for inclusion in the ASEAN Regional Forum (in 1996) and the East Asia Summit (in 2005). Even for the PSI (2004), President Bush sought to enroll India as a key participant through PACOM. However, even while India is located in PACOM’s area of responsibility, ‘technically’, it does not belong to the Asia-Pacific. During the Shangri, La Dialogue 2009, India’s former naval chief Admiral Arun Prakash highlighted this contradiction, saying,

“I am not quite sure about the origin of the term Asia-Pacific, but I presume it was coined to include America in this part of the world, which is perfectly all right. As an Indian, every time I hear the term Asia-Pacific I feel a sense of exclusion, because it seems to include north east Asia, south east Asia and the Pacific islands, and it terminates at the Malacca Straits, but there is a whole world west of the Malacca Straits…so my question to the distinguished panel is…do you see a contradiction between the terms Asia-Pacific, Asia, and the Indian Ocean region?”

The ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept helped to overcome this dilemma by incorporating ‘India’ in the affairs of ‘maritime-Asia,’ even though the ‘Indo-’ in the compound word ‘Indo-Pacific’ stands for the ‘Indian Ocean’, and not ‘India.’

Since long, the IOR had been a maritime-conduit of hydrocarbons to fuel the economic prosperity of the WP littoral countries, which was another significant linkage between the IOR and the WP, and provided much ballast to the rationale of ‘Indo-Pacific.’ In context of China’s economic ‘rise’ leading to its enhanced military power and assertiveness, this linkage represented Beijing’s strategic vulnerability, and thereby an opportunity for deterring Chinese aggressiveness. Ironically, China’s strategic vulnerability was expressed by the Chinese President Hu Jintao himself in November 2003 through his coinage of the “Malacca Dilemma,” wherein “certain major powers” were bent on controlling the strait.8 The reference to India was implicit, yet undeniable. In his book ‘Samudramanthan’ (2012), Raja Mohan says, “India-China maritime rivalry finds its sharpest expression in the Bay of Bengal, the South China Sea and the Malacca Strait…” which demonstrates the interconnectedness of “the two different realms (of) Pacific and Indian Ocean(s).”9

The Genesis

Against the backdrop of strengthening India-Japan political ties following the 2006 reciprocal visits of the two countries’ apex leaders, Indian and Japanese think tanks had intensified their discussions on strategic and maritime cooperation. At one of the brainstorming sessions held at the IDSA in October 2006, the participants took note of China’s strategic vulnerability in terms of its ‘Malacca Dilemma,’ and sought to stretch its sense of insecurity eastwards to the IOR with the objective of restraining China’s politico-military assertiveness against its Asian neighbors.

Besides, Japan itself was vulnerable due to its rather heavy dependence on seaborne energy and food imports across the IOR, and thus sought an enhanced maritime security role in the area in cooperation with India. During the discussions at IDSA, a clear concord was reached that the IOR and the WP cannot possibly be treated separately, either for maritime security, or even in geopolitical terms. It was during that event that the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept was casually discussed, which led to the publication of the January 2007 paper in Strategic Analyses (as mentioned above). Interestingly, a few months later in August 2007, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe addressed the Indian Parliament, speaking of the “Confluence of the Indian and Pacific Oceans” as “the dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and of prosperity” in the “broader Asia.”10

In 2010, the U.S. officially recognized ‘Indo-Pacific’ for the first time. Speaking at Honolulu, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke about “expanding our work with the Indian Navy in the Pacific, because we understand how important the Indo-Pacific basin is to global trade and commerce.”11

In 2012, the Australian analyst Rory Medcalf wrote that he was convinced that the “Indo-Pacific (is) a term whose time has come.” A year later in 2013, Australia released its Defence White Paper, which carried the first government articulation of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept.12 Soon thereafter, Rory Medcalf endorsed India’s centrality in the Indo-Pacific construct stating that “Australia’s new defense policy recognizes India’s eastward orientation.”13

China was initially circumspect of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ coinage. As the Australian writers Nick Bisley and Andrew Phillips wrote in 2012,

“…Viewed from Beijing, the idea of the Indo-Pacific…appears to be to keep the U.S. in, lift India up, and keep China out of the Indian Ocean… (which is why), the Indo-Pacific concept has…received a frosty reception in China…”14

In July 2013, Chinese scholar Zhao Qinghai trashed the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept on the basis of his interpretation of it being an “India too” geopolitical construct.15 Notwithstanding, not all Chinese scholars have been dismissive of the concept. In June 2013, Minghao Zhao wrote,

“…And it is true that a power game of great significance has unfolded in Indo-Pacific Asia. The U.S., India, Japan, and other players are seeking to collaborate to build an “Indo-Pacific order” that is congenial to their long-term interests. China is not necessarily excluded from this project, and it should seek a seat at the table and help recast the strategic objectives and interaction norms (in China’s favor).”16

Interestingly, in November 2014 the Global Times, an official Chinese English-language daily, carried a commentary cautioning India on the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept. It said that the Indo-Pacific concept has not been endorsed by the “Indian government and scholars,” but scripted by the United States and its allies “to balance and even contain China’s increasing influence in the Asia-Pacific region and the Indian Ocean,” and who have made India a “linchpin” in the geo-strategic system. Paradoxically, however, the commentary was titled “New Delhi-Beijing Cooperation Key to Building an Indo-Pacific Era.”17

Prognosis

It emerges from the foregoing that the current prevalence of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept is premised upon – and necessitated by – the growing inter-connectedness between the IOR and WP, rather than any similarities in their characteristics. This leads to another pertinent question: What would be the relevance of the concept in the coming years?

According to preliminary indicators, the relevance of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept may be enhanced in the future due to the strengthening linkages between the IOR and the WP. Events and developments in one part of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ are likely to increasingly affect countries located in the other part. Furthermore, over the decades, the growing trade and people-to-people connectivity between the IOR and WP countries may benefit the IOR, and slowly iron out the dissimilarities in terms of economic and human development indices.

China’s ‘Maritime Silk Road’ (MSR) and India’s outreach to its extended eastern neighborhood through its ‘Act East’ policy could contribute substantially toward the economic integration of the IOR and the WP. Indonesia’s putative role is also noteworthy. It is an archipelagic country that straddles the ‘Indo Pacific’ with sea coasts facing both the IOR and the WP. Possessing substantial potential to become a major maritime power, Indonesia is likely to be a key player in the process of melting the IOR-WP divide, and thereby reinforcing the ‘Indo-Pacific’ construct.

Over the decades, the current dissimilarities between the IOR and the WP in terms of the security environment may also diminish, if not vanish altogether. Greater economic prosperity in the IOR is likely to be followed by increasing stakes in the maritime domain, besides the ability to develop naval capabilities. The hitherto ‘dormant’ maritime disputes in IOR could become ‘active.’ Furthermore, the MSR could be accompanied by China’s invigorated efforts toward naval development to fructify its ‘Two-Ocean Strategy.’18 China’s intensified naval presence in the IOR could lead to increased likelihood of acrimony due to its politico-military involvement in regional instabilities and maritime disputes. It may also cause the PLA Navy to increase its activities in the maritime zones of IOR countries, and have unintended encounters at sea with the naval forces of other established powers, leading to enhanced maritime-military insecurities. In such a scenario, the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept would be essential to manage the regional developments and integrate China into the established norms of conduct in the IOR.

In the broader sense, as India’s leading strategist Uday Bhaskar avers, “In the global context, the Pacific and the Indian oceans are poised to acquire greater strategic salience for the major powers of the 21st century, three among whom – the China, India and the U.S. – are located in Asia.”19 Indeed, a holistic treatment of the Indian-Pacific Ocean continuum would be required to assess the evolving balance of power in Asia, and to address the fault-lines therein, with the overarching aim of preserving regional and global stability.

Captain Gurpreet S. Khurana, PhD, is Executive Director at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NMF, the Indian Navy, or the Government of India. He can be reached at gurpreet.bulbul@gmail.com.

Notes and References

[1] ‘Indo-Pacific: Strategic/ Geopolitical Context’, Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pacific

[2] Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation’, Strategic Analysis (IDSA/ Routledge), Vol. 31 (1), January 2007, p.139 – 153

[3] David Brewster, ‘Dividing Lines: Evolving Mental Maps of the Bay of Bengal’, Asian Security, Vol. 10(2), 24 Jun 14, p.151-167, at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14799855.2014.914499

[4] Shigehisa Kasahara, ‘The Asian Developmental State and the Flying Geese Paradigm’, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Discussion Paper No. 213, Nov 2013, at http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/osgdp20133_en.pdf

[5] ‘Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI)’, Arms Control Association, 2 Jun 2007, at https://www.armscontrol.org/taxonomy/term/21

[6] Japan and Australia promoted the term ‘Asia Pacific’ in the 1970s and 1980s to draw them closer to the United States and the economically burgeoning East Asia. India was far, geographically, from the region, and politically, economically and strategically remained uninvolved for inherent reasons. See D. Gnanagurunathan, ‘India and the Idea of the ‘Indo-Pacific’’, East Asia Forum, 20 Oct 12, at http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2012/10/20/india-and-the-idea-of-the-indo-pacific/

[7] Donald L Berlin, ‘India in the Indian Ocean’, Naval War College Review, Vol.59(2), Spring 2006

[8] Ian Storey, ‘China’s Malacca Dilemma’, China Brief (The Jamestown Foundation), Vol. 6(8), 12 Apr 2006, at https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-malacca-dilemma/

[9] C Raja Mohan. Samudramanthan: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: October 2012)

[10] Confluence of the Two Seas”, Speech by H.E. Mr. Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan at the Parliament of the Republic of India, August 22, 2007, Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) website, at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

[11] Remarks by Hillary Rodham Clinton, US Secretary of State, ‘America’s Engagement in the Asia-Pacific’, US Department of State, 28 Oct 10, at http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2010/10/150141.htm

[12] ‘Defending Australia and its National Interests’, Defence White Paper 2013, Department of Defence, Australian Government, May 13, at http://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper/2013/docs/wp_2013_web.pdf

[13] Rory Medcalf, ‘The Indo-Pacific Pivot’, 10 May 13, at http://www.indianexpress.com/news/the-indopacific-pivot/1113736/

[14] Nick Bisley (La Trobe University, Australia) and Andrew Phillips (University of Queensland, Australia), ‘The Indo-Pacific: what does it actually mean?’, East Asia Forum, 06 Oct 12, at http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2012/10/06/the-indo-pacific-what-does-it-actually-mean/

[15] Zhao Qinghai, ‘The Concept of “India too”(“Yin Tai”) and its implications for China’(translated from Mandarin “印太”概念及其对中国的含义), Contemporary International Relations (现代国际关), No. 7, 2013, 31 July 2013,at http://www.ciis.org.cn/chinese/2013-07/31/content_6170351.htm

[16] Minghao Zhao, ‘The Emerging Strategic Triangle in Indo-Pacific Asia’, 4 Jun 13, at http://thediplomat.com/china-power/the-emerging-strategic-triangle-in-indo-pacific-asia/

[17] Liu Zongyi, ‘New Delhi-Beijing Key to Building an <Indo-Pacific Era>’, Global Times, 30 November 2014, at http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/894334.shtml

[18] Robert D. Kaplan, ‘China’s Two Ocean Strategy’ in Abraham Denmark and Nirav Patel (eds.) China’s Arrival: A Strategic Relationship for a Global Relationship (Centre for New American Strategy: Sep 2009), p.43-58, at https://lbj.utexas.edu/sites/default/files/file/news/CNAS%20China’s%20Arrival_Final%20Report-3.pdf

[19] C Uday Bhaskar. ‘Pacific and Indian Oceans: Relevance for the evolving power structures in Asia’, Queries, Magazine by the Foundation for European Progressive Studies (FEPS), No. 3(6), Nov 11, p.123-128

Featured Image: Composite rendering of the Eastern Hemisphere of Earth, based on data from Terra MODIS, Aqua MODIS, the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program, Space Shuttle Endeavour, and the Radarsat Antarctic Mapping Project, combined by scientists and artists. (NASA/ Wikimedia Commons)

I just signed up to your websites rss feed. Will you post more on this subject?