By Travis Reese

“One of the greatest contributions of net assessment is that it calls for consciously thinking about the time span of the competition you are in.” –Dr. Paul Braken

“Short term thinking drives out long term strategy, every time.”–Herbert Simon, Nobel Prize-winning economist

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” The oft-repeated phrase from renowned author Peter Drucker continues to echo throughout defense circles and think tanks to catalyze change. Defense of the nation is a never-ending task achieved by balancing readiness for today’s threats and tomorrow’s challenges as part of a connected continuum. Yet, when it comes to addressing either current or future challenges, there is excessive lag between identifying needs and delivering relevant solutions. Senior leader dialogue often stipulates that the best assessments of needed capabilities come from operational commanders facing current problems. This is done while unironically pointing out the struggle to deliver capabilities in a relevant timeframe, often due to complex discovery relying on large human and capital investments. This dialogue is usually accompanied by a declaration that somewhere in industry exists a magic fix to the solutions delivery problem.

In response, industry and government research centers point to all the ways that the Department of Defense (DoD) is ineffective at discussing these problems earlier, while potential solutions wither away due to a lack of funds, institutional initiative, consistency of effort, or all three. To the DoD’s credit, Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks and Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Heidi Shyu have spearheaded initiatives for the DoD to improve future vision and analytic synchronization. Despite these initiatives, however, the culture around force design planning still eats strategy for breakfast, hindering if not outright stopping the delivery of timely capabilities. It is time to change the accepted practices of solutions discovery with a better method. A better method requires the DoD to establish multiple planning horizons with interactive comparisons between near-term and far-term designs stretched over 30 years.

The Problem

The DoD’s current planning horizons are ineffective at anticipating future needs and avoiding emergent gaps. This condition upsets the timely delivery of resources and capabilities because it keeps drawing the focus back to the “here and now” instead of the “there and later.” This leads to the constant refrain to “ask the warfighters” as the place where capability developers and program managers seek to find solutions to “here and now” problems as opposed to developing solutions for increasingly more capable “there and later” adversaries. This reactive response has the institution perpetually lagging. It also results in an abrogation of the Office of Secretary of Defense and the Service Chiefs’ responsibility to use their institutional mandates to forecast the “train, man, equip, and deploy” demands of the future. Instead, they often retrograde future force design issues onto current force employment problems.

This abrogation runs the risk of the entire defense enterprise doing what the late Colonel Art Corbett, designer of the Marine Corps’ Expeditionary Advance Base Operations and Stand-in Forces concepts, used to characterize as solving today’s problems with yesterday’s logic and being constantly surprised by the future. Relying on “warfighter” discovery followed by pressurizing the research, engineering, and acquisition communities to satisfy those demands should be a rare exception and not the norm. Warfighter discovery should exist for only the most unanticipated and untested concerns when the experience of conflict and day-to-day competition reveals unknown capacity of the adversary.

DoD must avoid strategic surprise by delivering well-considered solutions based on long-term forecasts coupled with risk-managed and informed investment. Implementing a process that preempts this persistent short fusing of acquisition effort and priorities can be done by conducting force development and force design based on three distinct time horizons paced over 30 years for the major security scenarios the DoD expects to face. With a long-term forecast model, the DoD can achieve a proactive strategy long before the majority of future challenges manifest as emergent gaps as is so often the case with today’s compressed institutional planning horizons of 10 years or less.

Static Logic Challenge

Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph Dunford stated in 2015 that “… adaptation is the things we’re doing right now with the wherewithal that we have, and to me innovation is…when you’re looking really for a fundamentally different way to do things in the future – disruptive, if you will. And so we’ve got to be able to do both of those things.”

General Dunford’s statement indicates that adaptation and innovation are unique ways to address solutions for emergent concerns and future challenges. The ability to identify the full range of innovative or adaptive solutions is often frustrated by the fact that future force planning frequently falls into two habits that create static logic: 1) fixation on the current security challenge which becomes an anchor to perceptions of the future which results in using the current state as the model for all future conditions (sometimes for 10 to 20 years) or 2) establishing a single point in the future and then using that point alone to design a future force with a constant interpretation of the threat regardless of new information or changes. This case frequently occurs due to the institutional inertia that builds up around a model as agencies work to align their programs and efforts to an accepted framework. Each change in the model often generates a halting effect on force development or design as organizations take years or better to adjust to a new conception of the future or threat.

A fix to the static logic problem to maintain innovation and adaptation would be to sustain a constant flow of future projections that mature in detail the closer to the period under question. For example, analysis in the 20-year timeframe may only be able to inform decisions to investigate options in basic or applied research and operating concepts whereas analysis in a 10-year timeframe, informed by years of prior learning, would focus on prototypes and tactical experimentation.

The logic of static time periods also generates a fixed appreciation of the adversary and does not account for their reaction to a U.S. action. The moment the U.S. introduces a capability it should expect an adversary to develop countermeasures. The cost imposing strategy of responding to a well-developed measure with a cheap countermeasure should change the timeframe the U.S. could expect usefulness from initial capabilities for a given timeframe and consider their replacements. For this reason, force developers should construct planning horizons that reflect adversary transitions vice working from a single model for 10 years. However, almost every major acquisition undertaken by the DoD requires 10, 15, or 30 years to develop and, in many instances, is used for 30 to 40 years. In 2016, then-Army Chief of Staff General Mark A. Milley described the purpose of exploring new operational concepts as simply to “get this less wrong than whoever opposes us.” It is the task of future force planning to avoid strategic surprise and orient the institutions into “less wrong” outcomes. This is especially true when force design and the capabilities development process requires 10 years just to move through the initial stages of identification, explanation, buy-in, and approval.

A problem of fixing the DoD on a single assigned year for force design is that potential solutions outside the window of consideration often get set aside in a conceptual limbo. The irony is that somehow these solutions are expected to emerge when the enterprise decides they are ready for the next 10-year horizon. The inability to hold multiple time horizons in consideration becomes a technology and solutions decelerator. Planning in more than one timeframe can overcome the “cold start” gap of discovery, convincing the institution of viability, and accepting it as a suitable option. When discovery and analysis take place on a consistent basis long before a solution is needed, the speed of execution and delivery will meet the judgment of relevance. Potential solutions will require less modification since they will be refined with increasing levels of detail or discarded earlier if determined to be unachievable. That which is not explicitly covered under the near-term approach could be considered and placed into a less committing but equally informing future case. It will give context to any range of research and experimentation rather than merely evaluating an option based on its technical interest or amorphous potential.

Developing 30-year horizons will facilitate continuity of institutional thought, long-term vision, and iterative tests of ideas before requesting or committing scarce resources for what becomes a strategy-defining requirement, that if unrealized, compromises the potential for future success. It is not about hedging bets but maximizing the exploration of options under managed timeframes to identify the greatest range of acceptable solutions, refined through iterative institutional learning and shared understanding.

What does the solution look like? The model for a new process.

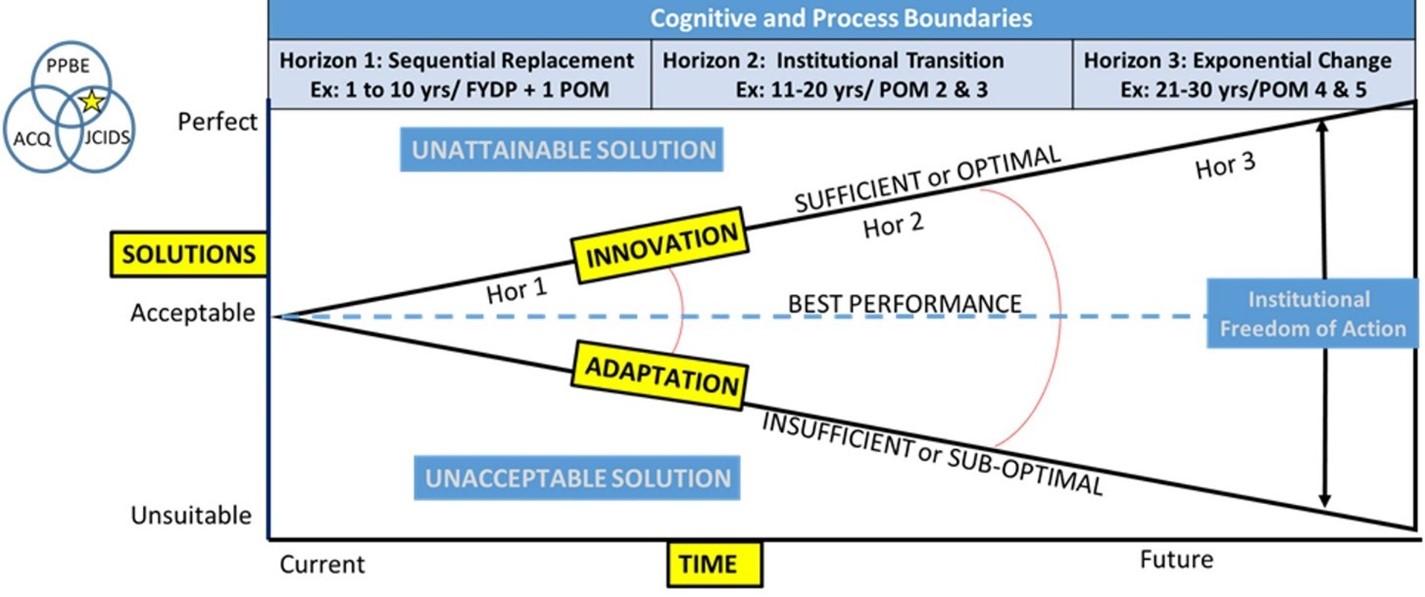

The Horizons of Innovation model provides a framework for three interactive but distinct institutional design horizons spanning from 10 to 30 years. The Y-axis, labeled “solutions” spans the spectrum from unsuitable to perfect. The X-axis, labeled “time” spans from the present into the future. Solutions are constrained by the positively sloped “innovation” line and negatively sloped “adaptation.” All solutions constrained in the angle formed between adaptation and innovation are acceptable where the bisecting dashed line represents the best performance. Solutions that exist below the adaptation line are unacceptable while solutions that exist above the innovation line are unattainable. DoD force planners should look at the limiting lines of innovation and adaptation across the three different horizons of 10, 20, and 30 years to develop the framework to address future challenges.

The Horizons of Innovation Model is adapted from the Three Horizons model introduced to business strategists around the turn of this millennia. Critics argue that horizons are too sequential and do not account for rates of change brought on by modern access to information. The combination of process and human factors in DoD force design, however, can still benefit from sequential framing because the Horizons of Innovation account for likely rates of change regardless of the potential spontaneity of innovation. The horizons model distinguishes between short and near-term achievability and distant long-term possibilities. The model shows the difference in thinking that simply makes sequential improvements, usually by only achieving competitive parity, along with paradigm shifting conditions, colloquially known as “game changers,” which create exponential changes in understanding that result in distinct advantages.

The Horizons of Innovation model provides a framework for three horizons. The Y-axis, labeled “solutions” spans the spectrum from unsuitable to perfect. The X-axis, labeled “time” spans from the present into the future. Solutions are constrained by the positively sloped “innovation” line and negatively sloped “adaptation.” All solutions constrained in the angle formed between adaptation and innovation are acceptable where the bisecting dashed line represents the best performance. Solutions that exist below the adaptation line are unacceptable while solutions that exist above the innovation line are unattainable. DoD force planners should look at the limiting lines of innovation and adaptation across the three different horizons of 10, 20, and 30 years to develop the framework to address future challenges.

Outside of the boundary formed by innovation and adaptation, two observations are readily apparent: 1) some desired innovation may be unachievable, but that possibility lessens over time and 2) some adaptations are suitable until obsolescence. Future opportunities are revealed as each new change gives a glimpse of the degree of disruption and benefit from that new understanding. The longer a problem is considered, the more likely abstract concepts of the future can be quantified. It is not a perfect understanding of the future but provides a model to identify areas that need investment to benefit from forecasted change.

The further one looks out, the greater the institutional freedom of action between innovation and adaptation. While the lines are linearly divergent, the difference between optimal and suboptimal solutions becomes greater with time. Any adaptation can be assessed to meet future demand and innovations can be identified that generate disruptive change. The model also shows that the closer in time to execution, the less institutional freedom of action there is. The longer future issues are considered, more possibilities could be explored. If a desired innovation is available sooner than expected, it could be seamlessly transitioned into an earlier horizon. This would create a phase shift up the vertical “solutions” axis, increasing advantage over an adversary. Conversely, if an expected innovation cannot be realized in time, the innovations can phase shift down. However, the loss of innovation is managed by shifting the lines of efforts from innovation to adaptation. The longer the institution looks into the future and evolves that understanding, the more risk accepting and opportunity seeking it becomes, vice risk averse and opportunity limiting. Allowing current force commanders to contribute their concerns to future analysis will prevent pinning the DoD just on “hear and now” concerns that in turn alleviates anchoring and availability bias in DoD planning.

While the Horizon’s model is agnostic of personal bias or viewpoints, there is still a human element in force design methodology. Novel solutions that change paradigms and alter the inertial course of massive institutional ships takes time. A contemporary example is found in the efforts of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General David Berger, to accelerate the naval service toward modernization by 2030. To casual observers, it seems that General Berger is the initiator of this effort. That is far from the truth. The lineage of the Force Design 2030 efforts trace themselves back to his predecessors throughout recent times. General Dunford began a force redesign in 2015, followed by the 37th Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Neller, and his introduction of Marine Corps Force 2025. Current iterations continuing under General Berger will cover a span of seven years. Despite having the full support of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Berger’s effort to modernize require explanation, convincing, testing, and advocacy. By the conclusion of his tenure as Commandant, the transition to a new force design will have taken nearly 10 years. This transition period beckons several questions: even as FD2030 falls into place, where is the next horizon? Have strategic leaders considered the frame that will emerge after 2030? Where is the guidance to evaluate the potential outcomes of the 2030 force? How will the adversary respond? What countermeasures/innovations must be developed?

Too often near-term executors are segregated from future visionaries as if they have mutually exclusive institutional roles. The model shows they are not distinct but complementary. Immediate pressures force the DoD to emphasize the near-term challenges and solutions that are biased and anchored in the present. These current concerns generate responses that are often risk averse because of the perceived potential for loss. Future speculation promotes a greater propensity to accept risk because the focus shifts from potential loss to potential gain. Collective discussion with involved stakeholders should be held in all three horizons simultaneously. This ensures that choices for institutional readiness can be assessed over the different time horizons which allow for an informed approach. Focusing exclusively in one time frame generates collective ignorance since it disregards the existence of the next range of options and opportunities. It is possible to be both a contemporary and future thinker simultaneously, which is necessary to assesses risk and balance the forces that are “here and now” with the forces that will be “there and later.”

An additional opportunity from this method is that younger generations will be inculcated in strategic thought and be exposed to the strategic environment they will face earlier in their careers. Advancing in one’s career with a sense of ownership over the potential challenges and being involved in the likely solutions will generate career-long strategic thinking. If adopted, the Three Horizons model enables transition of the future environment to successor generations. This could catalyze an educational shift to think critically and creatively both at the individual and institutional level ensuring the proper shaping of the future design of the force with each turnover of leadership. Current leaders can manage force sustainment challenges while sponsoring and investing in the contributions of future generations on an informed basis led by those who will inherit the outcomes.

Leaders that are reticent to engage in timelines beyond 10 years may do so because they fear how future considerations can be viewed as path determinant once they are discussed in public. This happens because there is no running institutional method of discourse to encourage evolution of thought over time. Rather, it remains a leader-managed process subject to the whims of the next decider rather than being a participant-driven enterprise with clear transitions and gates between ideation, iteration, and ultimate leader-required decisions based on legal obligations and restraints. Nothing substitutes for a well-considered problem with persistent investments of time and resources. Nothing improves support of an institutional direction like transparent stakeholder engagement on a persistent basis. The Horizons of Innovation model, with its three frames of replacement, transition, and exponential change, supports both and invites rigorous analysis at each step.

Conclusion

Horizons are not fixed limitations but rather means of effectively organizing referred to as “chunking,” and based on likely periods of technology development or institutional transition. This model can serve as an institutional tool for facilitating change, stabilizing the disruptive effects of innovation, programing the arrival of new capabilities, and replacing obsolete practices and models in a managed timeline. It enables detailed analytic approaches based on the continuous refinement of institutional design for the future with iterative adjustment. The Horizon model can enhance acquisition, programming and budgeting, and capability development processes by organizing stakeholders into common appreciation of long-term force design.

The current capabilities development process requires 10 years to move through the initial stages of identification, explanation, buy-in, and approval to generate needed solutions to likely military challenges 15 to 20 years on the future, let alone solve current problems and readiness challenges. Competitors and adversaries are executing on their long-term strategies and steadily growing their capabilities and capacities having followed a similar process of decades-long planning and organized action.

They have however accelerated towards their goals by harnessing steady and persistent momentum rather than attempting radical lurches based on short-term forecasts and near-term focus. Their ability to capitalize on a long-view approach, while critically analyzing our force (and that of our allies) is enabling them to progress toward strategic and operational overmatch. Adversaries’ planned transitions from current to future through managed modernization have resulted in our present challenges.

It is time to account for the role of those factors in the process for force design as well. Retired Australian Army Major General Mick Ryan, in a recent interview on his book War Transformed, articulated the case for balancing current and future when he described the cultural paradigm that needs to be overcome. He opined that democracies are good at leveraging 24-hour news cycles and 3 to 4-year electoral cycles. Conversely, he stipulated that if leaders want to exploit microseconds of opportunity that may only be possible through building the societal patience to think in decades.

The Horizons of Innovation model provides discipline to forecasting decades into the future. Although the future is uncertain, it is not a fact-free activity solely left for conjecture. Future planning can be a very informed process with logical designs and reasonable outcomes. When the Horizon model is used, these designs and outcomes will help define how current means satisfy requirements when adapted to new circumstances. The model also shows where the potential for disruptive innovation may be needed to avoid strategic surprise and overcome anticipated concerns. Famed Disney Imagineer and consultant to the DoD on future innovation, Bran Ferren stated, “We don’t do strategic or long-term thinking anymore. If anything, we may do long-term tactical thinking and call it strategic, but it’s really just a spreadsheet exercise…That’s not a survivable model.” Bran Ferren’s words articulate a pressing problem, and the Horizon model may just be the prescription to fix it.

Travis Reese retired from the Marine Corps as Lieutenant Colonel after nearly 21 years of service. While on active duty he served in a variety of billets inclusive of tours in capabilities development, future scenario design, and institutional strategy. Since his retirement in 2016 he was one of the co-developers of the Joint Force Operating Scenario process. Mr. Reese is now the Director of Wargaming and Net Assessment for Troika Solutions in Reston, VA.

Featured Image: JAPAN (Aug. 18, 2022) – U.S. Marine Corps F-35B Lightning II’s assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 participate in an aerial refueling mission during a 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit Certification Exercise over the East China Sea, Aug. 18, 2022. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Pfc. Justin J. Marty)

What an excellent article. Having just read Dr. Dan Goure’s “Pink Flamingo: The U.S. Military Will Pay for Its Munition Shortage” at nationalinterest.org, I was wondering how much short term focus in resource allocation contributes to that problem. I look forward to some detailed study of Mr. Reese’s ideas.

The Navy failed at long term planning three times during my active days. In 1973 in the Eastern Med we faced a Soviet fleet but we had no anti-ship tactics or weapons. In 1990 we showed up in the PG and Red Sea with no doctrine or C2 mechanism to conduct a progressive air campaign. In the early 90s the Navy had to forcibly retire senior officers while gapping their billets because in 1979 Navy planners did not think through officer requirements if the Service shrunk. The issue is not predicting the future but maintaining a balanced portfolio of capabilities to hedge for the unexpected.

Barney, I did not say predict the future once in the article. It was about developing a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis, and iterating on potential solutions. I also used the word scenarios (plural) to emphasize the range of threats and concerns that need to be considered. Nothing in my thesis neither stipulates prognostication anymore than trend analysis lets one consider nor does it establish a solitary unitary force model. Your concern regarding past strategic design failures is exactly what I’m trying to correct. My other article for Human Factors week on changing the leader and led paradigm in force design also talks about how to avoid the omissions in key issues like doctrine or manpower planning as well. In the end, all needed capabilities to address emerging threats or tactics require a future case and lead time to deliver the solution.

Travis, sorry, did not mean to say you were trying to predict the future, but even future cases have to be handled with care. What we did on the CS21 project was to get at longer term factors via a challenge and response process in which red and blue took turns reacting to the other’s strategic plans. After three iterations we thought we saw the central factor that would be relevant to our tasking.

No offense taken at all Barney, I just wanted to clarify for purpose of framing. I hate how tone gets lost at times. BTW, great article last week on wargaming. I reposted on LinkedIn and it got a fair amount of traffic. That’s a great point on CS-21. Certainly the idea here is do what you did with CS-21 but give it time to mature over a longer period. I think the results you hoped for (especially with some expected improvements in simulation tools) would be more likely (with appropriate caveat that I acknowledge it’s theoretical premise).

Travis, the other approach we used back in 2003 was to use an excessively challenging scenario as a kind of concept atom smasher to see how the Services’ future concepts fitted together. The quark that popped out was that nobody intended to maintain a SEAD capability, eithe relying exclusively on stealth or assuming one of the other Services would handle it. As a secondary insight the flags that were cell leaders determined that the US needed a global operational level command to coordinate logistics and possibly other matters since – wait for it – what happens in one AoR affects what happens in the others.