By LTJG Kyle Cregge

As the United States Navy looks to space and cyber as new domains for warfare, it also ought to look deeper: to the seafloor. Increased competition for vital resources and the intent to control critical sea lines of communication will drive nations and their navies to the seabed. There are three serious operational challenges ahead for the U.S. Navy that will require both technical and intellectual investment to properly establish security on the seafloor.

In the context of seabed warfare the three challenges align with the first three operational phases of war as part of U.S. doctrine: 0, Shape the Environment; 1, Deter Aggression; and 2, Seize the Initiative. In Phase 0, the U.S. will have to grapple with the difficulty of shaping an environment governed by an international legal structure which the U.S. is not party to. In Phase 1, the U.S. will be challenged to deter potential seabed exploitation by submarines and unmanned or automated underwater vehicles (UUVs or AUVs) in the vast depths of the oceans. Such platforms will be limited in their communication with other vehicles or fleet command centers due to their distributed use and the inability to communicate quickly, reliably, and secretly at great water depths. When the Navy is required to seize the initiative in Phase 2, open warfare, the seabed will serve to expand the enemy threat area beyond the first thousand meters of the water column thereby increasing risk for forces entering and exiting critical straits, bays, and other waterways, which will require the greater allocation of assets down into the depths.

The South China Sea and the Seabed: A Blueprint for Future Lawfare

Lawfare, as defined by Maj. Gen. Charles Dunlap (Ret.) of Duke University, is “the use or misuse of law as a substitute for traditional military means to accomplish an operational objective.” The U.S. Navy is continuously involved in combating lawfare, such as the recent freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) conducted by USS Hopper (DDG 70) in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea (SCS). While China claims these and similar operations are violations of territorial sovereignty, the U.S. executes the FONOPs in order to repudiate the excessive Chinese island claims, which, if otherwise accepted by international norms, would come with associated economic rights within the SCS.

The basis for the legal battle comes from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), that the United States has not ratified, but recognizes as customary international law. Despite the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration against China, island building in the SCS continues. Chinese lawfare for islands and their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) is a blueprint that many nations could use to exploit the seabed, specifically because the primary reason the U.S. did not ratify UNCLOS was disagreement with Part XI of the Convention which deals with, “[the] area of the seabed and ocean floor and the subsoil… beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources.” The United Nations “Reaffirm[ed] that the seabed… as well as the resource[s]… are the common heritage of mankind,” and that developed nations capable of seabed mining should share both profits of mining and the technology to do so. Though there were limited discussions at the U.N. in the early 1990s to assuage U.S. concerns, UNCLOS remains unratified by the U.S. Senate.

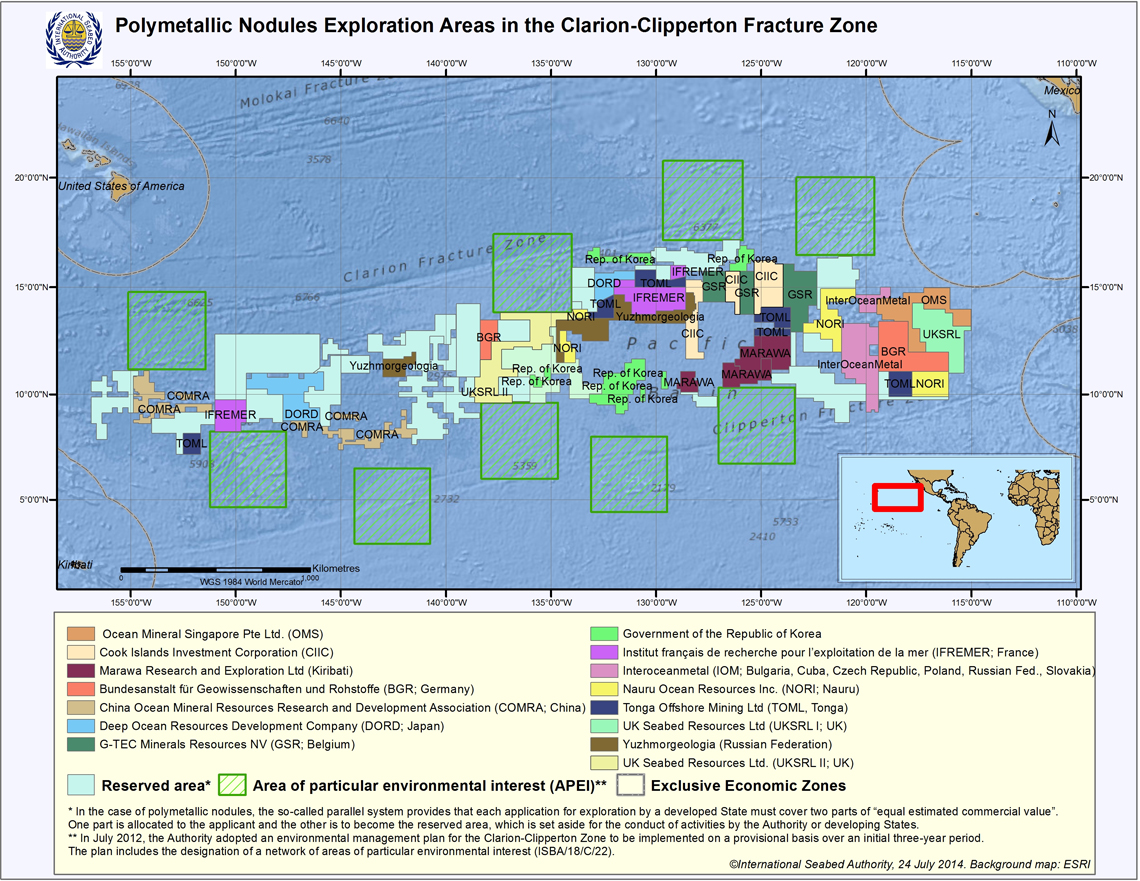

Under the current UNCLOS legal structure nations may extend their EEZ based on scientific study and submission approved by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. As the U.S. is not party to UNCLOS, there are no U.S. members on the Commission, nor are there currently U.S. civilian contracts for seabed exploitation through the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The ISA regulates the nearly 50 percent of the Earth which is outside the jurisdiction of national territories, and has contracts to explore for and potentially mine various lucrative metals with Russia, Japan, China, India, the UK, France, Germany, South Korea, Brazil, and other smaller nations. Without a cohesive national strategy or participation in an international legal framework, the United States government has left the shaping of the environment and the execution of national maritime strategy up to the otherwise apolitical Navy at the fleet operational level. Not only is there risk to U.S. forces failing to communicate intent clearly, but other near-peer nations will continue to use political lawfare to shape international norms to their preferences as the Chinese have in the South China Sea.

Seabed Deterrence: Limited Communications, Command and Control

As the Navy will shape and potentially deter actions at the seafloor, the assets called on to execute that mission will include surface ships, submarines, and AUV/UUVs. UUVs will be the only asset able to operate at the seabed, due to their ability to survive and work at depths beyond the first thousand feet of water, where submarines normally operate. Depending on the particular type of seabed exploitation, AUVs and commercial mining vehicles could be operating anywhere from 2,500 – 20,000 feet, with the support of surface vessels recovering both the vehicles themselves and the resources being mined. Yet while the depth of the water will be an issue for the Navy, the breadth of possible areas of operation is also staggering. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), which contains numerous polymetallic lodes ripe for mining, is a great deep-water plain as wide as the continental United States in the eastern Pacific Ocean. And while there will be competition in and around the Pacific Rim, global warming and further development of seabed mining technology has unearthed the Arctic Circle’s available resources to be mined which includes coal, diamonds, uranium, phosphate, nickel, platinum, and other precious minerals and hydrocarbons. As nations including the United States seek to establish firm economic claims on the seabed, there is the potential for a massive area for coverage, defense, and support of the U.S. flagged seabed mining expeditions (as the U.S. Navy has supported oil platforms in the Arabian Gulf before) by a Navy already strapped for forces required in other areas around the world.

Yet even if industry is able to rapidly develop a low priced AUV or UUV the Navy could serially buy, the UUVs will still be bound by the restrictions of massive water depths. Communication to a UUV at hundreds of meters below the water will at best be limited to the ELF spectrum, requiring massive antenna to transmit short messages, or using acoustic transmissions that would give away the position of a UUV to any enemy UUV’s passive sonar system. Other options include having the UUV surface for radio or satellite communications, or using a buoy to do the same while the UUV remains below the surface. Artificial intelligence may help in such a communications restricted environment by giving some level of control to a UUV with expected return and update patterns, but at the operational level UUVs will be not be a perfect solution in Phase 1, where potential escalation could happen rapidly due to a miscalculation. What might a near peer nation do if it was found that an AUV had sunk another AUV at the seabed? Or more critically, what if the AUV sunk a submarine or surface ship?

The U.S. Navy must think through all these potential ROE considerations before allowing lethal capability on an AUV, so that a computer’s miscalculation resulting in a seabed skirmish would not grow into an undesired broader conflict. Regardless of lethal autonomy, the U.S. Navy will continue to struggle to integrate unmanned systems in all domains. But deep-water seabed presence will remain especially difficult to properly resource for patrolling, as well as maintaining control of those assets, and communicating commander’s intent while deterring diverse enemies over massive areas.

Seizing the Initiative: Keeping the SLOCs Open

In a proposed Phase 2 environment, the seabed will be a fertile ground for exploitation by military assets, primarily as an extension of mine and anti-submarine warfare. While it is possible to imagine a strike warfare or air warfare capability, it would be incredibly difficult technologically to maintain assets such as missiles at the seabed in a ready configuration for extended periods to then be launched either at land targets without a ready communication system to initiate the launch, or at air threats when the system would lack an indigenous radar or missile guidance system. It is far easier for less complicated mines, torpedoes, or UUVs to be moved slowly along the seabed or deployed in waiting for a worthwhile target such as a ship or submarine. And much like in land warfare where terrain is critical, the Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) and the seafloor in the vicinity will be critical to control. SLOCs and other strategic maritime chokepoints have always been important, but much as the use of the seabed extends the water column for submariners, it will also expand the threat area posed by seabed mines and torpedo-capable UUVs. The U.S. Navy is already struggling to develop replacements for its aging Mine Counter Measures (MCM) fleet and an Explosive Ordnance Disposal team would be unable to access deeper seabed mines, given the incredible depths. The Navy would have to rely on other UUVs or Remotely Operated Vehicles to clear an area with limited certainty due to both the massive space required to clear, and the ability for more threats to be moved in via the seabed after time.

One can imagine the threat this poses either offensively or defensively to the Navy’s fleet. Commercial traffic for a large portion of the East Coast could be hampered if a vessel was sunk in the Chesapeake Bay by a seabed AUV during a broader conflict with a near-peer competitor. A UUV capable of traveling via the seabed could cross large portions of the oceans slowly, then maintain a position in a critical strait, bay, or harbor, unbeknownst to an enemy: waiting on a cue to activate and target enemy shipping or military vessels. Beyond homeports and harbors, seabed mines and UUVs could drastically change both the logistics and employment of forces for the U.S. Navy if critical waterways were infested with numerous AUVs hunting specific acoustic signatures. The Navy’s ability to deploy warships to key maritime regions, such as the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal or Bab el-Mandeb Strait, could be completely denied by seabed-based platforms. Similarly, the thought process that the Navy used historically with the GIUK (Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom) Gap is instructive. There, a listening network provided cues to friendly submarines to get underway and track Soviet submarines when they entered critical waterways. In the future, seabed listening stations could cue AUVs to track, report, and kill enemy UUVs, ships, and submarines.

Conclusion: An Arms Race

While the U.S. Navy will be tested to operate at or near the seafloor in the future, there is reason for hope. First, while the U.S. Navy will have difficulties reliably communicating with seafloor assets due to the environment, so too will its rivals. Second, all nations are vulnerable to seafloor-based attacks, which means the U.S. Navy could just as easily go on the offensive if attacked. Third, the costs associated with developing a sustainable deep water seabed military asset will remain expensive for all nations, and prohibitive for most, as no nation currently has UUVs able to withstand the pressure at depths of thousands of feet. Nevertheless, the United States will have to determine how it will shape its own law-based national security strategy considering America’s failure to ratify UNCLOS. At the operational level, seabed UUVs will likely lead to an arms race given all of the discrete tactical opportunities they offer. In an inversion of land warfare, control of the low ground will grant victory on the high seas.

Lieutenant (junior grade) Kyle Cregge is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He served on a destroyer and is a prospective Cruiser Division Officer. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or Department of Defense.

Featured Image: Photo via actor212 from Flickr.