By LT Jeff Vandenengel, USN

Bottom Line Up Front

The submarine force is highly capable but not near its full warfighting potential. Several factors limit submariners’ ability to prepare for safe deployments during peace and combat-effective operations during war. These factors include:

- Massive time obligations

- Limited training resources

- Extensive deployment administrative burdens

This two-part article outlines options to address these problems and thus enable submarine officers and crews to better prepare for the job only they can perform: at-sea operations and combat.

Introduction

Training for at-sea operations and combat has always been a primary concern in the U.S. Navy, and today those missions are more important and more difficult than they have been for decades. The recent fatal mishaps involving USS Fitzgerald, USS John S. McCain, and ARA San Juan, along with potential adversaries’ rapid technological advances, underscore the importance of training in the naval profession.

Warfighting training and preparations are especially crucial in the submarine force, which the Navy will rely on heavily in war. Today’s force of just fifty-three fast attack (SSN) and four guided-missile (SSGN) platforms are accomplishing vital missions during peacetime and will play a disproportionately important role in wartime.1 That outsized role will be accomplished by submarine wardrooms comprising less than two percent of all active duty naval officers and by crews comprising approximately three percent of all active duty sailors.2 With so much riding on so few, the submarine fleet must ensure its officers and crews are trained and ready to employ the warships the Navy has worked so hard to build and maintain.

Unfortunately, massive time obligations, limited training resources, and extensive deployment administrative burdens are severely impairing submariners’ ability to conduct effective training. As a result, the submarine force is not near its full warfighting potential, despite incredible technology, excellent material readiness, and the best people the country has to offer. Fortunately, there are numerous personnel and administrative solutions that would significantly improve each boat’s warfighting ability.

The Navy recently completed two excellent analyses of recent fleet mishaps: the Comprehensive Review3 and Strategic Readiness Review.4 These meticulous, constructive products closely analyzed the fleet’s problems to make substantive recommendations. To complement those high-level studies, this bottom-up “deckplate review” is submitted as an analysis of the Navy’s challenges from the viewpoint of an operational warship, with recommendations that would enable that ship to operate more safely and effectively.

It is important to note that the author and his fellow officers made these recommendations with a limited frame of reference and without complete knowledge of the Navy’s status with regards to personnel, budgets, training facilities, equipment, certification processes, logistics, and legal requirements. However, as the end users of all those lines of effort, it seems this feedback should be worth some measure of consideration.

The Navy and submarine force’s leadership have wisely instructed the fleet to focus on warfighting above all else. This paper details recommendations that would enable operational warships to meet that commander’s intent. Part One focuses on time constraints affecting the submarine fleet’s ability to focus on training. Part Two focuses on other problems that arise once submariners find time to train, both in their homeports and while deployed.

Factor 1: Time Constraints

“The ships, aircraft, and men and women of the Navy are finite resources. Those who man our ships are limited in the amount of time they have to perform equipment maintenance and build their warfighting skills…The core and primary competence of sailors must be mastery of naval warfighting skills.”– ADM Gary Roughead, USN (Ret.), and the Hon. Michael Bayer Secretary of the Navy Strategic Readiness Review5

The single largest factor limiting submarine warfighting training is officer and crew time. With numerous demands on their time, submariners are too often prevented from focusing on the job only they can do —tactically employ their warship — because they must accomplish tasks that supporting commands can assist with or perform more effectively.

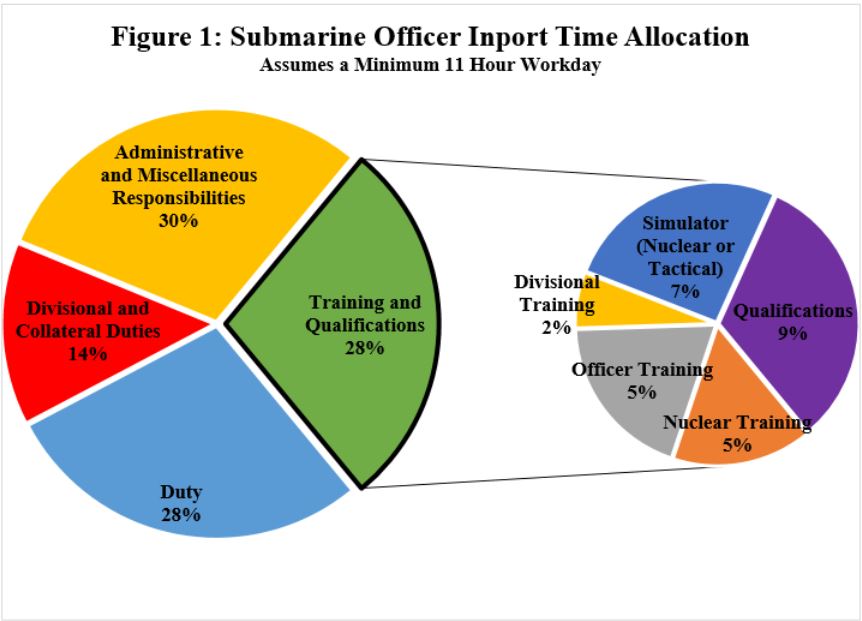

The wardroom is the best example of a submarine training group limited in its ability to prepare because of time constraints. As the only group to span the nuclear and non-nuclear worlds, the officers have numerous responsibilities that occupy almost the entirety of their workweek. Assuming an eleven-hour workday in port, officers spend an estimated 28 percent of their time standing duty, 30 percent of their time completing administrative and miscellaneous tasks (meetings, monitors, planning, etc.), and 14 percent of their time fulfilling divisional and collateral duties, leaving 28 percent of their time to complete training and qualifications.6 However, this time encompasses a vast array of training topics and requirements which span the tactical, nuclear, divisional, and maintenance areas, in addition to simulators and qualification interviews for junior personnel. This in-port time allocation is summarized in Figure 1.

What results is a strapped wardroom running from event to event, regularly working into the night and on the weekends to catch up. Despite carefully planned schedules, it is rare for all officers to attend all mandatory events because of overlapping demands. Even when an officer finds him or herself with free time, it is often in small blocks and rarely coincides with the rest of the wardroom, limiting the training he or she can effectively accomplish.

When the Navy assigns an officer to a task, part of that decision is based on the importance of the task and a lack of faith that someone else — a Chief Petty Officer (CPO) or non-ship’s force individual — could execute it properly. These many tasks help the ship improve its combat potential, either through improving its material condition, finding and fixing deficiencies, or developing the crew. While the importance of these tasks is not up for debate, the ability for someone besides an officer to accomplish them is debatable in every single instance except one: combat. No other group on a submarine has the training, holistic ship knowledge, access to information, and experience to fight the ship. However, when the vast majority of officers’ time is accounted for, the unintended consequence is that there are fewer opportunities for concentrated training on the numerous important warfighting topics that only they can perform. With so much information to teach officers and so little time to do it, most warfighting training is stuck at the basic level.

Fortunately, three categories of officer and crew time — in-port watch-standing, divisional and collateral duties, and administrative responsibilities — have opportunities for improvement that would allow for more focus on the fourth category of training and qualifications.

In-Port Duty

Standing duty, both as the Ship’s Duty Officer (SDO) and Engineering Duty Officer (EDO), undoubtedly improves the ship’s material condition and warfighting readiness. However, with a limited number of qualified officer watchstanders available, each officer must stand on average more than one duty day per workweek. Swamped with work controls, maintenance execution, inspections, and administration, there is little hope of study or training on those days. The amount of time spent on watch in port increases when ships use work control production officers or enter shiftwork, periods that can last days or weeks at a time. Throughout the author’s recent four-month dry-docking maintenance availability, an average of 29 percent of available qualified officers were on watch at any one time.7

The challenge is to reduce the time officers stand duty, allowing them to conduct more effective training together, without causing a reduction in the maintenance execution, security, or professionalism onboard. To meet those requirements, some basic ground rules were used when developing these options. There should always be at least one ship’s force unrestricted line officer onboard, either as SDO or EDO. There cannot be a reduction in watchstanding ability, as both SDO and EDO are challenging positions pivotal to fixing the ship and getting it back out to sea. Additionally, the use of duty alternatives should only occur during the day when needed to support training, with the wardroom resuming its normal duty roles at night to minimize the effect on supporting commands and individuals. Ship’s force would still stand most of the watches during the workweek and all of the watches outside normal working hours.

Engineering Duty Officer

For EDO alternatives, the submarine force could train and qualify Limited Duty Officers (LDOs), officers from the Engineering Duty community, submarine junior officers (JOs) on shore duty, Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) civilian Shift Test Engineers (STEs), or nuclear-trained CPOs. Most of these options are already being executed in different parts of the submarine fleet.

LDOs, with their years of nuclear training and experience, are already standing duty on pre-commissioning submarines. Similarly, members of the Engineering Duty community are already heavily involved in maintenance planning and execution onboard ships, with many of their officers laterally transferring from the submarine community. Another easy option would be to use submarine JOs on their shore duty as “duty augment officers.” Submarine JOs are already standing 24-hour watches on their shore duty, such as Shift Engineers at the Nuclear Power Training Units (NTPU) or as duty officers on pre-commissioning units, and so it is likely that many would be interested in being “duty augment officers” where they are only required to stand duty on weekdays during normal working hours. Alternatively, submarine JOs who have transferred to the Reserve Component (RC) could also be activated to perform this function.

In addition to using different officers for EDO, the submarine force could employ the highly trained STEs of NAVSEA’s Nuclear Engineering and Planning Department.8 During major availabilities, these dedicated civilians, with more than two years of nuclear training and an in-depth knowledge of the engineering plant, work with the EDO to complete numerous complex evolutions. The EDO and STE literally stand next to each other throughout the entire day, giving orders that they must both concur on before executing. The submarine force should authorize STEs to relieve as EDO in order to not duplicate supervision, allow the STE to lead the complex engineering evolutions that he or she knows best, and allow the submarine line officer more time to focus on the warfighting task that only he or she can execute.

The final option for EDO alternatives are nuclear-trained CPOs. This is also a proven model, as CPOs are already successfully standing EDO at the NPTUs. However, with a limited number of nuclear-trained CPOs on board SSNs and SSGNs, there are not enough of them available to support their watch bill plus the EDO position without changing their manning.

None of these options—LDOs, Engineering Duty community officers, shore duty JOs, STEs, or CPOs—would be attached to the ship. Rather, they would work from squadrons and be shared amongst the boats, ready to relieve as EDO during the day as needed, granting the ship’s force officers much-needed time to conduct training. This way, just a few augment options could serve an entire squadron, assisting whichever boats are in port.

Ship’s Duty Officer

There are also numerous options to augment SDOs, with the right controls in place. Currently, SDOs must be qualified Surfaced Officer of the Deck (OOD) so that they are ready to get the ship underway in the event of an emergency. However, there are many days that it would be impossible for the ship to get underway in any reasonable amount of time, such as when in drydock or during major engineering maintenance evolutions, negating the need to keep an OOD continuously onboard. If the submarine fleet relaxes this requirement as a function of the ship’s readiness condition, then there are alternatives to making the ship’s force officers always stand SDO. Additionally, augmenting SDO instead of EDO has the added benefit of avoiding the extensive although necessary certification and administration associated with standing watch on a naval nuclear power plant.

Shore duty JOs would be an attractive option for SDO just as it is for EDO. Some of these officers could be from the Naval Reserve, serving a year of obligated service before retirement. If the ship is not going underway and there is a line officer standing EDO, then Supply Officers should qualify and stand SDO to ease the duty rotation, as they are already doing on surface ships. Finally, CPOs could qualify SDO to temporarily relieve during the workday. This option is more attractive for SDO than EDO because of the larger number of non-nuclear vs nuclear CPOs available to flex to watch-bill burdens.

Enlisted Duty

Enlisted duty also stands in the way of better tactical training. Sonar, Fire Control, Torpedo, Navigation, and Radio Divisions would all greatly benefit from more in-port time to focus on their advanced skillsets. However, when they are manning a three- or four-section duty rotation, it becomes very difficult to free a majority of the division for any extended period while also completing necessary maintenance.

Most in-port watches require ship’s force sailors due to the level of knowledge required, but topside security watches could easily be outsourced to supporting commands. These watches are vital to protecting the ship, but do not require extensive training or certification. This off-hull support could come from Masters at Arms, Naval Reservists, or sailors on their shore duty attached to squadrons, again ready to support whatever boats are in port. Just as with officer support, ship’s force sailors would still stand the majority of the watches, but would receive assistance from these augment alternatives. Reservists have already assisted with SSGN security watches while overseas, and this model should be expanded to SSNs in their homeports during normal working hours.

Making Tough Choices About In-Port Duty

There are numerous options for standing SDO and EDO: ship’s force officers, LDOs, Engineering Duty community officers, augment shore duty JOs, NAVSEA STEs, and CPOs. However, only the ship’s officers can stand OOD, Contact Manager, and Engineering Officer of the Watch at sea and in battle. Similarly, there are numerous options for standing enlisted security watches in port, but only the submarine’s sailors can stand Fire Control Technician of the Watch, Torpedo Room Watch, and Passive Broadband Operator underway. Shifting a small portion of the in-port duty burden to these alternatives would free up desperately needed time for the ship’s officers and sailors to focus on the jobs that only they can perform.

Collateral Duties

Common themes when the Navy assigns collateral duties to submariners:

- Smart, hard-working submariners will put in the time and energy to tackle the challenge

- Those submariners will be completing their collateral duties at a steep opportunity cost: preparing for at-sea operations and combat

- In many cases, supporting commands can accomplish those collateral duties more effectively and efficiently

When submariners are not on watch, they have an array of collateral duties that again occupy their time and inhibit an at-sea focus. Responsibilities such as Quality Assurance Officer (QAO), Scuba Diving Officer, Radiation Health Officer, and Cryptologic Security Manager all make the submarine a more capable warship. However, significant parts of these jobs can be more effectively completed by specialized supporting commands, freeing submariners to focus on their primary functions.

The many shore commands and organizations that task submarines each rightfully strive to execute their respective programs. Most designate a ship’s force officer to be responsible for those programs knowing that it will maximize their chances of administrative success. Many of these programs are not individually overwhelming, and so the external commands apply moderate pressure to ensure the officers properly execute them. However, the cumulative effect of these various commands’ dictated programs is a culture in which submarine officers are constantly pulled in all directions except training for safe and combat-effective operations at sea.

To the junior sailors and officers on the deckplates, the Navy’s decisions to implement many new programs or requirements can seem to be made in a vacuum and without consideration of the reality of shipboard life. Each task is a good idea by itself, but crammed into already full workdays they rob those sailors and officers of time to focus on what matters.

Lots of good ideas with lots of unintended consequences are improving the submarine force’s collateral duties while distracting it from its primary function.

When everything is important—Audit and Surveillance Programs, Radiation Health Programs, Full Speed Ahead Training, Lessons Learned messages—nothing is important, including warfighting.

Procedure Development and Quality Assurance

Properly researched and written maintenance procedures are key to the ship’s material condition. While most of these are provided to the fleet, there are still numerous maintenance evolutions that have no provided procedure. This forces sailors and officers to research, write, review, and approve their own procedures, typically as Formal Work Packages (FWPs) or Controlled Work Packages (CWPs).9 This is a challenging process that requires numerous technical manuals, access to parts research, and a significant amount of time to do an adequate review. During a maintenance period, petty officers, divisional CPOs, division officers, department heads, and at times even the commanding officer (CO) must write, review, or approve several of these each week, with much of this effort duplicated on each boat in a class. Incorrect FWPs and CWPs can lead to critiques, rework, lost underway days, personnel injury, equipment damage, or loss of the ship in extreme cases.

Many of these maintenance packages are reviewed by the QAO, a JO who has attended a two-week school. Because that JO is dedicated to his submarine’s success, he will devote significant time and energy to properly execute the QA program. He will dig into the technical manuals, carefully review the Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual (JFMM), and conduct thorough parts research to ensure the work is done correctly and the ship can safely get to sea. Despite his intelligence and diligence, his lack of experience and time will prevent him from ever being as proficient in Quality Assurance (QA) as the people running the squadrons’ and regional maintenance centers’ QA offices. These administrators are typically retired CPOs and LDOs working full time on QA, able to draw on their expertise to produce quality products without the distractions of submarine life.

To both alleviate a time demand on the QAO and numerous other submariners and to ensure they execute maintenance correctly the first time, more procedures should be written and approved off the ship. These could be standardized as Reactor Plant Manual (RPM) procedures and Maintenance Requirement Cards (MRCs) or provided as FWPs and CWPs. This will reduce the duplication of administration across boats, improve the quality of procedures, and allow the ships to focus on their execution. This will not work for all procedures, as many will still have to be tailored to a ship’s unique conditions or equipment.

The newly developed Automated Work Package Generator (AWPG) is a great start to combating this problem. Retired QA experts research and write CWPs and periodically provide them to the fleet for use. However, boats are not allowed to simply use these quality packages, but must still complete the full review process. Additionally, the AWPG only covers a small fraction of all the procedures submarines must write on their own.

Maintenance and engineering organizations off the ship are better at writing and approving technical procedures than submariners are. Submariners are better at employing their warships at sea. To produce a submarine fleet that is both in better material condition and more effectively trained for sea, the submarine fleet should transfer as many procedure writing responsibilities from the boats to supporting commands as possible.

Scuba Diving

SSN’s Scuba Diving Divisions perform important functions including hull inspections, component cleanings, and serving as rescue swimmers. They are also another example of a program that makes the ship more capable but at a cost.

To meet the required number of personnel in Dive Division, submarines must send an officer and several sailors to Dive School. During this six-week period they are lost to the ship and completely unable to train on their primary warfighting duty. When they return, they must perform all the required maintenance, training, dives, and inspections in addition to their normal duties.

The Supplemental Preliminary Inquiry on USS Fitzgerald’s June 2017 collision contained numerous examples of astonishing courage exhibited by the crew as they struggled to save their ship. It also contained a statement likely surprising to many submariners: Fitzgerald and surface ships “have no dive equipment aboard, nor do they have trained and qualified divers.”10 If surface warships and SSBNs are not required to man Dive Divisions, then the rest of the submarine fleet, with smaller crews and less space for gear stowage, should follow their example.

All SSN homeports have specialized divers that perform all the boats’ advanced maintenance and inspections, and these could be used to accomplish the dives currently being done by ship’s force. These specialized divers are highly trained, well equipped, and dive as their primary responsibility, making them a more proficient and safer alternative than submariners fulfilling a collateral duty. When pulling in for deployment port calls, most US Navy ports again have divers that could perform required inspections or maintenance. Additionally, flyaway teams could support boats when in foreign ports without U.S. Navy diver presence, a model the surface fleet is already employing. In war, port calls would all likely be at U.S. Navy ports, negating the need for those flyaway teams. Boats at sea could employ Search and Rescue (SAR) swimmers as surface ships already do, ready to respond in case of a man overboard. Transforming the ship’s divers into SAR swimmers would greatly cut down on the time lost to school, administration, maintenance, and inspections.

Just like QAOs, Scuba Diving Officers are going to work tenaciously to lead a safe and effective program. However, with their schedule so packed, the time they spend focusing on Dive Division is time they do not spend studying the Nautical Rules of the Road, how to safely proceed to periscope depth, or how to recover the reactor in the event of a scram at sea. Finally, just as with QA, there are supporting organizations off the boat that will always be better at the task because of their experience, specialized equipment, and singular focus.

Miscellaneous

There are numerous other collateral duties that follow a similar theme of being important to the submarine, but more effectively performed by someone not aboard that submarine. The Navigation and Operations Officer, as the security officer, initiates Secret security clearances for everyone onboard when it comes time for their renewal. However, squadron Special Security Officers (SSO) could easily take on this task and free the Navigator to focus on the safe planning and operation of his ship. SSOs already initiate Top Secret clearances for submariners, as well as all Secret clearances when the boat is out of contact on deployment. SSOs should continue that support when boats pull back in.

The Radiation Health Program, led by the executive officer (XO), helps ensure the crew’s long-term health by tracking their radiation exposure. However, the administratively burdensome program detracts from the XO’s ability to fulfill his primary duty of Training Officer. To refocus XOs—and prepare them to be the next Dick O’Kane under the next Mush Morton—much of the Radiation Health programs should be outsourced to squadron Undersea Medical Officers or squadron Independent Duty Corpsmen. These specialists are better suited to yield a quality product, allowing the XOs to focus on crew training. At sea, XOs would still be responsible for the Radiation Health program, but in port they would be relieved of these duties.

Maintaining proper inventories and controls of cryptologic keys are an obviously vital task for the submarine and the entire fleet. Because it is a painstaking process that the fleet is obviously concerned with, a CPO and JO are tasked with leading the program with a great deal of oversight from the CO. However, there are options to shift the administration off the boats by making them simple end-users, significantly cutting down on the time and paperwork associated with the program. The Navy should fully implement this proposal to free a CPO and JO from yet another task and, more importantly, give the CO more time to focus on what only he can accomplish.

Other tasks such as the Safety Program, Ship Systems Manual (SSM) page updates, gauge calibration, and painting could all be partially outsourced to a combination of shore duty sailors, reservists, specialized supporting teams, or civilians. Each task is small, but when sailors are sleeping at work for duty every third or fourth day, accomplishing incredible amounts of maintenance, and pushing to accomplish numerous qualifications and training sessions, every little bit helps.

Conclusion

“In many cases, our biggest challenges and opportunities for improvement are at [the junior officer and chief] scale of the command. By virtue of piling on meaningless collateral duties and programs that contribute little to operational and warfighting excellence, we have confused these leaders, making it hard for them to see through the chaff and to prioritize the personal and professional development of their people.”- ADM John M. Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations Message on Navy-Wide Operational Pause11

None of these tasks — maintenance procedure development, scuba diving, radiation health, security investigation initiation, cryptologic security management— are by themselves a huge burden on the ship. Together, they are a constant pull on submarine officers and crews, minimizing the time they can devote to what truly matters — warfighting.

The submarine force can continue to use ship’s force officers to stand SDO and EDO, to demand they write and review numerous FWPs and CWPs each week, and to expect them to execute numerous collateral duties. That would be the simplest option because it is how the undersea fleet has operated for decades and because it is the safest choice for when the submarine is in port. However, the unintended consequence is that once the submarine returns to sea, its officers and crew will be less safe and tactically adept than they could be if they were given the time to properly prepare.

Part Two of this article will focus on other problems that arise once submariners find time to train, both in their homeports and while deployed.

LT Vandenengel is the Weapons Officer on USS Alexandria (SSN 757). He developed this paper with a working group of submarine officers. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Department of Defense. You can reach him at jeff.vandenengel@gmail.com.

Endnotes

1.“Fleet Size,” Naval Vessel Register, last modified April 9, 2018, accessed April 15, 2018, http://www.nvr.navy.mil/NVRships/fleetsize.html.

2. “Navy Demographics,” U.S. Navy Fact File, last modified September 29, 2017, accessed October 1, 2017, www.navy.mil/navydata/nav_legacy.asp?id=146. Assuming 53 SSN crews and 8 SSGN crews of 16 officers and 140 sailors each.

3. Admiral Philip S. Davidson, USN. “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents.” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Fleet Forces Command, October 26, 2017).

4. The Honorable Michael Bayer and Admiral Gary Roughead, USN (Ret.). “Strategic Readiness Review.” (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of the Navy, December 3, 2017).

5. Ibid, 78-79.

6. Assumes each officer stands six duty days per month, equating to 1.4 duty days per five-day work week. “Administrative and Miscellaneous Responsibilities” include monitors, audits, meetings, planning sessions, miscellaneous requirements (such as flag visits or one-time training sessions), a thirty-minute lunch, and 2.5 hours of unaccounted for time weekly.

7. Estimating twelve qualified watch officers, with two unavailable due to the Prospective Nuclear Engineer Officer (PNEO) course. Various engineering evolutions and testing periods required additional watches such as night-shift EDOs and SDOs, Senior Supervisory Watches, and production officers.

8. “Nuclear Engineering and Planning Department, Code 2300,” Naval Sea Systems Command, accessed November 25, 2017, http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Home/Shipyards/Norfolk/Department-Links/C2300-Nuclear-Engineering-and-Planning-Department/.

9. Executive Director SUBMEPP, “Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual,” Revision C Change 5. (Portsmouth, NH.: Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Department of the Navy, 11 August 2016), Part I Volume V Chapter 2.

10. “Supplemental Preliminary Inquiry and Line of Duty Determination Regarding Injuries and the Deaths of Seven Sailors Aboard USS FITZGERALD (DDG 62) On or About 17 June 2017.” (Yokosuka, Japan: Commander, Carrier Strike Group FIVE, 2017), 16.

11. Admiral John M. Richardson, USN. “CNO Richardson Message on Navy Operational Pause,” USNI News, October 6, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/10/06/cno-richardson-message-navy-operational-pause.

Featured Image: DIEGO GARCIA (Sept. 8, 2011) Sonar Technician (Submarine) 2nd Class Jeff Wiesmaier, left, Chief Fire Control Technician Johnathan Taylor, Missile Technician 2nd Class David Laymon, MachinistÕs Mate 1st Class Cody Henry and MachinistÕs Mate 3rd Class Christopher Smith secure the Los Angeles-class attack submarine USS Dallas (SSN 700) in Diego Garcia. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Chris Williamson/Released)

Excellent – very constructive ideas! How would some of these manifest outside of the large and well supported squadrons and IMAs aka Guam?

Several of the truly administrative programs outlined should be reviewed and shifted to the ISIC/NSSC/IMA/TYCOM… However, I disagree with shifting duty and maintenance responsibilities for a couple reasons. First, it’s about ownership. Submariners fix their gear because they go to sea and submerge the ship. You are committed to excellence because your life is at stake. Everyday at sea on a submarine is a fight against the ocean. Keeping it all bay and outside the people tank is priority one. No matter how dedicated a shore side maintainer is, they will never feel the same responsibility for theirs and their shipmate’s lives as the people that take the sub to sea and sink it on purpose. Second, maintaining your gear and gaining in-depth knowledge of its operations is a war fighting skill. When stuff breaks at sea in a war, it’s up to you to fix it and continue the fight. That takes years to develop. By the time you are a CO it is you and a couple of Chiefs that have seen just about everything. If you growup as an Officer not having experienced material issues and been intimately involved in their maintenance or repair, you won’t, as a CO, be ready to assess risk at sea and fight the ship when it is still possible or pull it off line when you know it’s not. You won’t be able to ask the IMA. It will be you and your team making that call. The tactics pubs don’t cover that.

When in port, training resources are limited, we need more. When we are at sea we need to shoot more Ex-torps, more countermeasures, and conduct more high end exercises…that takes money. The in port duty watchbill is not your master. You adapt it so the people you need to train are available. The issue is we use trainers around the clock and we don’t get many reps and sets because resources are limited and a lot of crews must share. When you are assigned OPFOR duties in an exercise, do you run the points and conduct engineering drills or do you challenge your crew to plan an operation to the max extent allowed by the scenario guidelines. Do you simulate firing point procedures while in the local op areas at PD or maneuver the ship to simulate approach and attack scenarios, conduct simulated ISR or do you clear the broadcast and stay on PIM…a submarine crew must be able to do many things in parallel. A call for more CODT should be coming from all corners of the force. Give our Skippers the time to train their crews at sea.

The article at times seems to suggests that tactical war fighting training is the only important duty of a submarine officer and that perhaps single focusd Serial learning and operations would improve our war fighting capabilities. I disagree. I think that approach would dilute our culture and make us less. What makes Submariners “special,” is our ability to multi-task at a high level. It is also a war fighting skill and an advantage if and when we are called to fight and win. Submarine Officers cannot solely be a tactical warfighter. They must be that of course, but so much more.

Three thoughts:

1. Recognizing that an 11-hour day is probably generous (you further state that the crew often works well into the night, and weekends), Big Navy needs to think seriously about crew fatigue. It’s well-documented how even minor fatigue approximates and exceeds the impairment of drugs or alcohol. Fatigue has been a contributing factor in multiple naval casualties and mishaps. The can-do attitude of sailors and submariners will mean folks keep taking on more and more, until bad things happen. Big Navy should consider IMO rest requirements (minimum 10 hrs’ rest every 24 hrs, with at least 6 of that in an unbroken period; minimum 77 hrs’ rest every 7 days) and create regulations that “bag” our surface and subsurface forces the same way pilots reach max hours. This will force Navy planners to recognize they cannot keep piling more and more onto the deckplates and devolving their responsibility to COs and junior leaders to “manage.”

2. The Navy needs to trust machines. A lot of what humans do aboard ship can be, and is, done by machines in the civilian/commercial world, and in other countries’ navies. Yes, we need people who understand how to monitor and manage machines. But we need to take advantage of the technological innovations of the past 50 years that allow machines to competently do much of the work humans used to do. Save the manpower for the times when it’s really needed (e.g. close-quarters navigation; combat or near-combat situations).

3. Move the training off the ship. One reason that civilian, commercial, and other countries’ navy ships can operate with much smaller manning is that the sailors/submariners show up fully trained and qualified. Time is not wasted aboard ship trying to train and qualify oneself or supervise the training of others. Training is primarily conducted ashore, with standardized curriculum and qualified/experienced instructors; students who cannot pass do not proceed to a ship. Students spend time in simulators or go to sea for short periods of time to practice what they are learning. But every ship/submarine is not a training platform. Vessels are reserved for accomplishing the mission, with a fully trained and qualified crew. Moving training to the schoolhouse also removes many of the management and disciplinary problems that crop up with a largely untrained, unqualified, inexperienced, and overtasked workforce trying to educate each other.

I also wholeheartedly concur with Craig Hempeck above: standing watch is critical to building proficiency; and, active and engaged watchstanding is where sailors/submariners should be learning and practicing to fight the ship. Every watch should be an opportunity to discuss or safely experiment with techniques, tactics, and procedures to locate and defeat the adversary.

I commend your group for working on this project and hope that those up the chain will listen to your suggestions.

Your #3 won’t work. While people can show up qualified, the ship must still train as a team. This is simple human truth. Ever seen a ‘great all-star game? And no group of awesome all stars could beat one full time team of professionals. Besides, do what, not train. For the time you are on the ship? No one does that in any complex field.

I could have been clearer: My recommendation was to move qualification training off the ship, as they do in Commonwealth Navies and civilian marine jobs.

Using your sports analogy, this would mean making sure people had the requisite skillsets, as demonstrated by meeting a certain level of game-day performance, before moving up into the major leagues.

As you highlight, mission-related training is a key focus once people report to the ship. Relocating the qualification training to the schoolhouse will give folks a lot more time to focus on mission-related training aboard ship – and ensure they are working with a team where everyone meets basic performance standards.

While I have issues with some of the ideas, overall I support these initiatives. For years and in many billets I worked unsuccessfully to move the burdens off the ship. Two simple examples: why not have ship’s divers simply complete the PADI open water course…if even that much is needed; why are there no fleet wide approved drill guides? In almost every case the barrier is that the ship must be accountable. To that I say of course, yet we provide RPMs, SSMs, OPs and tons of other stuff. Drill guides, random FWPs, rad health and more are not outsourced simply because noone else wants the pain. To this day I can hardly believe we don’t force ELTs to read TLDs anymore. What will we do when a machine does chemistry? Oh wait, it does, and we still write deficiencies.

I agree that outsourcing everything will diminish the force, but quit holding onto things just because it was ‘harder for me.’

I recently read that Nuc (and I presume, sub) qualified EMs can qualify for $100K reenlistment bonus. I was a Nuc EM on a fast attack. I had 30 hour work days in port and often 40, 50 and 60 hour days at sea. My last 2 years, in port and at sea, I had port & stbd watches. At the end of my six years I volunteered to reenlist on the condition I got gas turbine school. The O-gangers were surprised I didn’t love being a Nuc. I got out and got a great job in IT. If you want to meet someone who loves his job, talk to a Ruby or Javascript developer.

Here’s why being a submariner is difficult:

1. Requirements increase, while manning decreases.

2. Nobody cares about 3-M

3. People that used to be on submarines, forgot what it was like to be on submarines…I.E. Inspection teams!