This publication originally featured on Bharat Shakti and is republished with permission. It may be read in its original form here.

The article will be presented in two parts. In this part, the author explores China’s dependence on crude oil that traverses across the oceans to feed the country’s growth. These circumstances have prompted China to develop its naval forces, since its greater security concerns are in the oceans. The author initiates his discourse on Chinese strategy by detailing the foremost core imperatives that drive the Communist Party of China and its stated core national interests.

By Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan AVSM & Bar, VSM, IN (Ret.)

Much thought needs to be given to possible politico-military circumstances under which the Government of India might realize that a Sino-Indian military build-up, stand-off or confrontation is no longer a mere skirmish between their respective armies but a clash in which the Republic of India in its entirety becomes engaged in armed conflict against the People’s Republic of China. Within the context of these circumstances—themselves a matter of both conjecture and debate—this article seeks to initiate an analysis of contemporary Chinese military strategy, using the concept of “reach.”

In common with many such analyses, China’s White Paper of May 2015 forms the basis of our understanding of China’s Military Strategy, i.e. the plans by which the country’s military seeks to achieve national objectives at the strategic level.

The core imperatives that drive the Communist Party of China’s relationship to the State and the State’s relationship with the world at large include: 1) regime survival 2) “saving face” 3) domestic stability and 4) territorial integrity.

These resonate well with the more formally-stated six core national interests of China: 1) state sovereignty 2) national security 3) territorial integrity 4) national reunification 5) China’s political system established by the Constitution and overall social stability and 6) basic safeguards for ensuring sustainable economic and social development.

The commonly used term core interest, as used by the Chinese leadership, does not have direct correspondence with the same term used by India or, for that matter, by almost all other nation-states. The People’s Republic of China uses the term “to signal a more vigorous attempt to lay down a marker, or a warning, regarding the need for the United States and other countries to respect (indeed, accept with little if any negotiation) China’s position on certain issues”—in other words, “issues it considers important enough to go to war over.”

Along with the exponential growth of China’s “outward-leaning” economy in recent decades the country has experienced an equally meteoric increase in the geopolitical clout that it wields. Geopolitics is largely the sum of geoeconomics and geostrategy. Consequently, as China’s geoeconomic power has affected and dwarfed other regional and State economies, its asserted geostrategy has incrementally incorporated an number of geographic regions as its “core interests.” Examples include Xinjiang, the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea, and very nearly the whole of the South China Sea.

China’s geoeconomy has not only generated a more aggressive geostrategy but has also marked an inclination for other nation-states to acquiesce to China’s latest “core interest.” Within the Chinese state-apparatus, this acquiescence appears to have been understood as tacit acknowledgement of China’s intrinsic and inherent superiority to all other geopolitical entities and peoples. This concept of self is driven by the millennia-old Chinese belief that China is the “Middle Kingdom,” at the very center of global civilization, surrounded by barbarian vassals. It is a view that largely defines China’s sense of national identity. Thus, amongst the Chinese power-elites within the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Central Military Commission (CMC), the lack of any “pushback” from other global and regional powers to China’s assertions has led to a sense of disdain bordering on hubris.

In analyzing China’s military strategy, it is essential to understand three central features of the People’s Republic. The first is the critical importance of continuity and supremacy of the CPC. The second is the Chinese economy. The third is the uniquely Chinese concept of “face.” All three are closely linked. If the economy should falter or fail, the continuity of the CPC (regime continuity), or at the very least its continued supremacy, will become uncertain. Likewise, the Chinese sense of identity is inextricably linked to this concept of face and a national loss of face is likely to be far less acceptable than a mere “temporary” loss of territory or military assets. This critical feature offers India several military-strategic options in dealing with China.

The 2015 White Paper clarifies that China characterizes outer space and cyberspace as the “new commanding heights in strategic competition among all parties.” It likewise declares China’s intent to focus upon building a reliable second-strike capability. However, the sharpest thrust has been reserved for the oceans, which is understandable given the prominence that the 2015 White Paper accords to the contemporary strategic concerns of the People’s Republic. These strategic concerns include America’s pivot towards the Indo-Pacific, Japan’s recasting of its military and security policies, and the resistance being offered by Philippines and Vietnam to China’s 9-Dash Line and its assertive activities in the Spratly Islands.

The Chinese Armed Forces are charged with the preservation and protection of the country’s core interests, and this tasking determines China’s military strategy. As war evolves towards “informatization,” a key strategic task of Chinese armed forces is safeguarding China’s security interests in new domains such as Global Positioning Systems, Electronic Warfare (EW) and Cyber/Information Warfare. The latest White Paper has also reaffirmed the centrality of active defense as the guiding strategy for China’s military forces. Thus, offense at the tactical and operational levels is consistent with an overall defensive orientation at the strategic level. By this logic, cyber-attacks are integral elements of the Chinese military’s efforts to “resolutely safeguard China’s sovereignty, security and development interests” in cyberspace. Indeed, in the cyber and maritime domains alike, Beijing consistently rationalizes assertive activities as justified responses to prior provocations.

Despite the inevitable hype that has accompanied analyses of the 2015 White Paper, this is a Chinese strategic concept that predates the People’s Republic itself. Its first articulation within China may be attributed to Mao Zedong, the CPC’s founding chairman, who codified it in a much studied 1936 essay on the “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War,” which outlined “the strategy that the Red Army used in order to overcome stronger Nationalist and Japanese opponents—right from the Party’s inception in 1921 until its greatest triumph in 1949.”

“Active defense may be accurately described as a strategically defensive posture that a big, resource rich but (militarily) weak combatant assumes to weary and turn the tables on a stronger antagonist. Such a combatant needs time to tap its resources—natural riches, manpower, martial ingenuity—so it protracts the war. It makes itself strong over time, raising powerful armed forces, while constantly harrowing the enemy. It chips away at enemy strength where and when it can. Ultimately the weaker becomes the stronger contender, seizes the offensive, and wins. It outlasts the foe rather than hazarding a battle early on—a battle where it could lose everything in an afternoon.”

Obviously, a nation needs physical and strategic maneuvering space to work this strategy. Originally, this strategy was confined solely to the geospatial imperatives of the land war fought by the Red Army, wherein Mao’s peasant troops had the luxury of withdrawing into the remote interior of China. This move forced the enemy forces to choose between breaking contact and ceding the initiative or giving chase and overextending themselves. In the latter case, Red Army units, operating closer to their own logistics base could raid and harry the overstretched enemy, cut supply routes, and fall upon and annihilate isolated units. It was a strategy that the Russians, too, had used a century earlier when, in 1812, they seduced Napoleon deep into the Russian interior, leading to military disaster for France.

The term active defense remains contemporary in militaries other than the People’s Republic of China. The US Department of Defense, for instance, also uses the term, albeit predominantly (if not solely) with distinctly tactical connotations and defines it as “the employment of limited offensive action and counterattacks to deny a contested area or position to the enemy.” The Chinese, however, apply this as a general strategic principle applicable across all levels, from the tactical to the strategic. At the level of geostrategy, the required “maneuver space” shifts from the hinterland to the largely maritime expanse of the Indo-Pacific.

Here, the concept of strategic maneuver has intimate linkages with geoeconomics, much of which, as a result of the geographic element within that term, is maritime in nature. As the renowned Chinese Professor Lexiong Ni put it, “When a nation embarks upon a process of shifting from an ‘inward-leaning economy’ to an ‘outward-leaning economy,’ the arena of national security concerns begins to move to the oceans. This is a phenomenon in history that occurs so frequently that it has almost become a rule rather than an exception.”

Perhaps a good way to understand the application of this strategy at the grand-theater level is to simply abandon the lexicon of the standard Western approach to active defense, which in Indian analyses is all too frequently simply “copied-and-pasted,” and instead examine this stated strategy through a different prism, one that I call “reach.” We need to consider reach as an overarching ability with internal (e.g., political/societal) as well as external (geopolitical) facets and with spatial as well as temporal dimensions.

Internal reach may be considered as the ability to tap into the intrinsic sources of China’s strength—its people (including its global diaspora) and their conditioned sense of identity, their value system with the centrality that it gives to the concept of “face,” their industriousness, their innovativeness, their ability to reverse-engineer everything from contemporary and evolving concepts to cutting-edge and state-of-the-art military-hardware, their fierce determination to regain “face” that was lost in the Century of Humiliation and to not lose it ever again, etc. This is, in effect, the contemporary re-creation of the Chinese people as a roughly homogeneous mass—the peasant army in a modern, sophisticated avatar—no longer peasants but retaining the quality of “mass” all the same.

At the geoeconomic level, economic reach is the ability of China to build its own economy and sustain its economic growth by gaining and maintaining access to geographically diverse external sources of economic wealth (whether by way of access to raw materials from foreign lands or through market expansion of Chinese products in foreign lands). China’s geostrategy translates economic reach into geographical reality over a time frame that is predetermined by the state.

In other words, at the geostrategic level, strategic reach is the ability to shape the probable battlespace by enabling access and logistic support to Chinese commercial and State entities (including military entities) throughout China’s areas of geopolitical interest, so as to enable and/or facilitate economic reach while avoiding placing all geoeconomic eggs in a single basket.

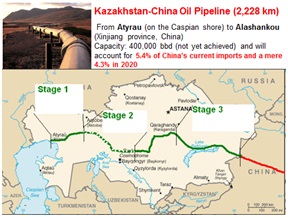

In some cases, this geoeconomic reach can be realized within a purely land-centric (continental) frame of geographic access. For instance, Mongolia, which has substantial reserves of high quality coking coal, is an important focus of China’s overland strategic reach. Likewise, Russian overland exports of oil, gas and

minerals (especially iron ore) increasingly feed the voracious economic appetite of China and have catapulted China into Russia’s largest trade partner, ahead of Germany. In the case of Vietnam, too, where the principal exports to China are oil and coal, a significant amount of the trade is overland, since the 1,300 km border is shared between the Chinese provinces of Yunnan and Guangxi and eight provinces of Vietnam. Both China and Vietnam have invested billions in highway and railway infrastructure to facilitate their bilateral overland trade. China’s significant imports of refined copper and copper ore from Laos also move predominantly along overland trade routes.

However, to meet the ever-growing demand for mineral resources and petroleum-based energy that is required to sustain China’s economic growth, the bulk of China’s imports of these resources are being drawn from increasingly distant areas that are either accessible only by sea or where seaborne transit offers the most cost-effective movement in terms of volume, time, and space. In fact, the maritime component of her geostrategy is so large that China is increasingly forced to venture into the uncertainties of becoming very nearly a pure maritime power. In China today, there is widespread recognition that a competent and well-balanced blue-water navy is the only military instrument that can obtain and sustain a favorable geopolitical situation in all the dynamic shifts that characterize international relations between China and the nation states upon which her geoeconomy depends. Indeed, the economy is simultaneously China’s greatest strength and its greatest vulnerability, and therefore, it is the centerpiece of the country’s policy and strategy. This is, of course, true of India as well.

However, to meet the ever-growing demand for mineral resources and petroleum-based energy that is required to sustain China’s economic growth, the bulk of China’s imports of these resources are being drawn from increasingly distant areas that are either accessible only by sea or where seaborne transit offers the most cost-effective movement in terms of volume, time, and space. In fact, the maritime component of her geostrategy is so large that China is increasingly forced to venture into the uncertainties of becoming very nearly a pure maritime power. In China today, there is widespread recognition that a competent and well-balanced blue-water navy is the only military instrument that can obtain and sustain a favorable geopolitical situation in all the dynamic shifts that characterize international relations between China and the nation states upon which her geoeconomy depends. Indeed, the economy is simultaneously China’s greatest strength and its greatest vulnerability, and therefore, it is the centerpiece of the country’s policy and strategy. This is, of course, true of India as well.

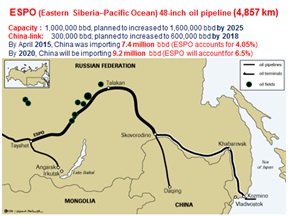

An ever-increasing demand for energy fuels China and India’s economic growth. Although the share of coal is still the largest in the energy-basket of both countries, oil consumption is growing so rapidly that it is driving the foreign policy and security perspectives of both China and India. In 1985, China was East Asia’s largest exporter of oil. In 1993, China became a net importer, and in 2015, she became the largest importer of crude oil on the planet. By April 2015, China was importing a staggering 7.4 million barrels per day (bbd) and by 2020, China will be importing an estimated 9.2 million bbd of crude-oil.

An ever-increasing demand for energy fuels China and India’s economic growth. Although the share of coal is still the largest in the energy-basket of both countries, oil consumption is growing so rapidly that it is driving the foreign policy and security perspectives of both China and India. In 1985, China was East Asia’s largest exporter of oil. In 1993, China became a net importer, and in 2015, she became the largest importer of crude oil on the planet. By April 2015, China was importing a staggering 7.4 million barrels per day (bbd) and by 2020, China will be importing an estimated 9.2 million bbd of crude-oil.

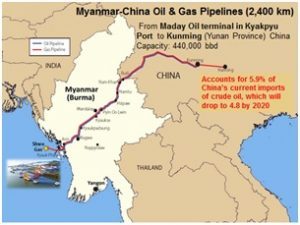

For all the marvelous engineering, the three main crude oil pipelines into China (the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO), the Kazakhstan-China oil Pipeline and the Myanmar-China oil pipeline), taken in aggregate, cater for a mere 15% of China’s crude oil imports. Almost all of the enormous quantity of crude oil that China imports either lies within or must travel across the Indian Ocean and must transit one or more of the chokepoints that connect the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. These are: the Malacca Strait, the Sunda Strait, the Lombok strait, and the Ombai-Wetar strait. Of these, the Malacca Strait and the Lombok Strait of are particular importance to China and constitute what Chinese leaders term the “Malacca Dilemma.”

For all the marvelous engineering, the three main crude oil pipelines into China (the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO), the Kazakhstan-China oil Pipeline and the Myanmar-China oil pipeline), taken in aggregate, cater for a mere 15% of China’s crude oil imports. Almost all of the enormous quantity of crude oil that China imports either lies within or must travel across the Indian Ocean and must transit one or more of the chokepoints that connect the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. These are: the Malacca Strait, the Sunda Strait, the Lombok strait, and the Ombai-Wetar strait. Of these, the Malacca Strait and the Lombok Strait of are particular importance to China and constitute what Chinese leaders term the “Malacca Dilemma.”

It is prudent to remember that the terms “energy security” and “security-of-energy” are not mere semantic variations. Energy security is the degree to which the available or assured and affordable energy exceeds the demand. The security-of-energy, on the other hand, is the physical security of the energy as it flows across or under the sea or over the land. Consequently, China, as a country, concerns itself with energy security, while the Chinese Navy concerns itself with the security-of-energy.

Conscious of all this, China is executing a geostrategy that will enable her to assure her geoeconomic needs. As in the famous Chinese game of Go, the People’s Republic is putting in place the pieces that will shape her desired geopolitical space.

The second part of this article will explore China’s geostrategic execution further.

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan retired as Commandant of the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala. He is an alumnus of the prestigious National Defence College.