By Christopher Nelson

Cord Scott knows a lot about comic books. In fact, while reading his book, Comics and Conflict: Patriotism and Propaganda from WWII through Operation Iraqi Freedom, I tried counting how many comic books he mentions. What began as sheer curiosity turned into a lot of pencil marks. I gave up counting by the second chapter.

Comics and Conflict is not for the casual comic book fan. So if you are curious about Namor’s superpowers, or when the Hulk first appeared, well, look elsewhere. What it does do, and does well, is tell us how wars have influenced comic books, and how comic book heroes have reflected our culture – for better or for worse. Recently I had the chance to ask Professor Scott a few questions about his book and comic book culture today.

Professor Scott, thanks for joining us. Congratulations on writing an interesting book on the history of comics and war from WWII to post-9/11. It’s encyclopedic in scope, truly. How did this project come about?

This project started from two different areas. I remember reading a lot of comics as a kid when I was at a friend’s house, specifically the old DC war titles: Sgt. Rock, G.I. Combat and Unknown Soldier. My brother also started collecting the little GI Joes in 1982, and I started reading the comic book from Marvel that went with it – that in and of itself was a genius marketing move – so there has been an interest in comics for a while. However when I was in college my collecting days halted for a bit. More specifically, I was teaching at a design college in downtown Chicago when 9/11 occurred. I had been teaching a class in the history of propaganda, and was always looking for extra material, especially from a cultural perspective. Captain America was one of the first characters to tie into US military doctrine, while being part of a cultural medium, comic books. Anyway, I was reading a newspaper article not long after the event and had read about the creators at Marvel who were writing a specific issue that dealt with the attack. This was the now famous “all black cover” Amazing Spiderman 136. I was at a comic book shop picking that one up, and had noticed a Captain America graphic novel with a Nazi logo and the shop owner noted that Captain America was being brought back to fight terrorism. So I picked up these issues when they were published and used them in the class. Later on I was taking a graduate class in Cultural history at Loyola and the comics became the basis for the paper.

I noticed in your book that a lot – if not all– of the pictures of comic books are from your personal collection. How many comics do you have in your collection? Which one is your most valuable comic?

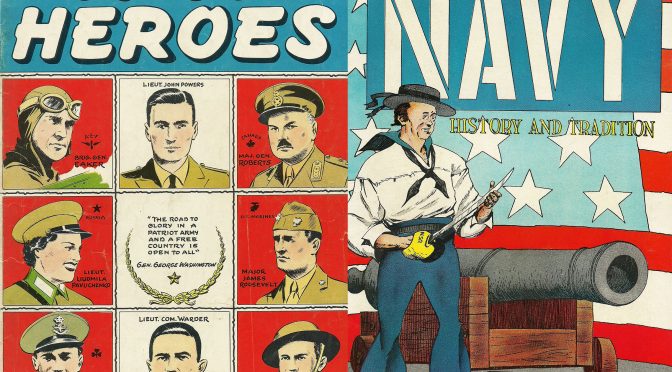

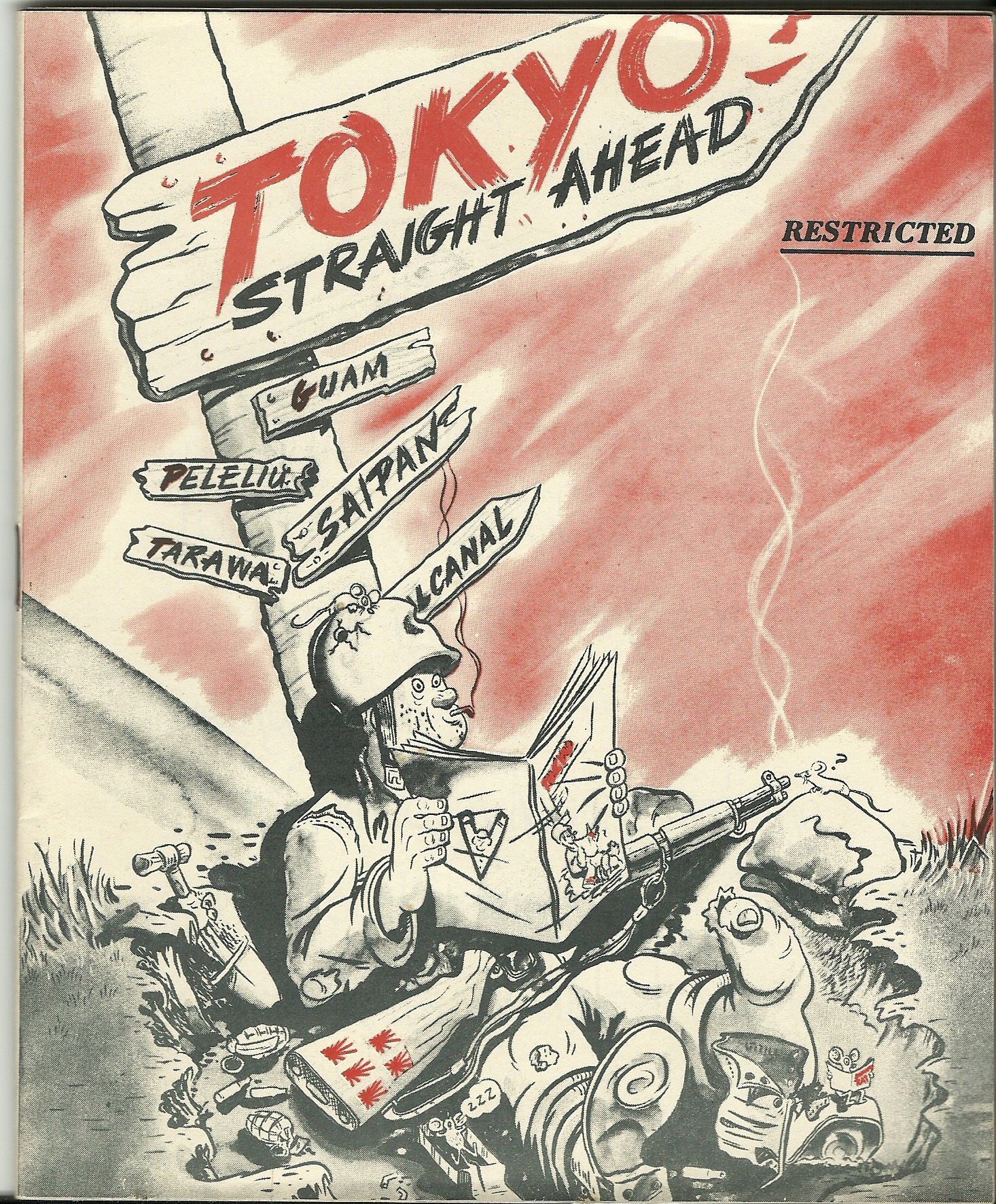

I have about eight long boxes worth, plus a couple dozen of trade paperbacks (reprints into one volume) and graphic novels (stand alone stories) as well. It’s pretty extensive and a pain in the butt to move! I have a lot of older ones (actual comics from WWII entitled True Comics, another entitled War Heroes, America Is Ready and Boys and Girls can Help Uncle Sam Win the War) but most were purchased for the stories and are not great as far as collectability is concerned. I would say that the most expensive comic item I own is most likely Remember Pearl Harbor, which was published right after Pearl Harbor. I also have a comic-related lithograph of Captain America which was done by Jim Steranko to raise money for 9/11 victims which was a bit expensive to me. I don’t buy a lot of them for their value and I certainly don’t own anything worth Sotheby’s interest. I also have a few items done by comic book artists for the military. I have a restricted comic training book for the UMUC entitled Tokyo Straight Ahead, and a couple of Joe Dope posters and some Army Motors journals, all done by Will Eisner.

In your opinion, who were the comic book heroes (or anti-heroes) that represented major conflicts in U.S. history? Why?

While many were incorporated into the US war effort early on, Captain America is still the oldest and biggest one directly tied to military conflict. While a lot of famous characters were brought into the war effort in WWII, Cap was really the most successful one that endured. There have been some great ones that are gone now. My personal favorite was Mr. Liberty, later Major Liberty, a mild mannered history professor who is turned into a superhero by the spirits of America. Cap was used briefly in the Red Scare of the 1950s. The Hulk was a take on nuclear testing. Tony Stark, AKA Iron Man, was an arms manufacturer that dealt with the Vietnam War prior to official US involvement. The Punisher was formed by his experiences in Vietnam – he was introduced in 1974 and was an anti-hero. There are more but these would be the most direct.

As for characters that have been icons, Sgt. Rock was the big one. He was introduced in ’58, and was around for 30 years as a continual character. As a side note, the late Joe Kubert not only did work on Sgt Rock from the beginning but also worked on PS Magazine which features comics to show periodic maintenance in the US army. Sgt Fury is still around but has morphed over the years from war hero to spy.

What was the Golden Age of comics? For someone who follows comics closely, do you see a resurgence in comics that might portend a second Golden Age in comics? I mean, for example, Comic-Con attendance is growing yearly. And Marvel and DC comic movies will be, in all likelihood, some of the highest grossing films in the future.

I see a continued interest in comics but I personally don’t think that there will be a second Golden Age. There are too many competing forms of entertainment. However, I do think that comics continue to thrive as they bridge the literary aspect and the visual realm. Think of them as storyboards for the movie creation. They also provide ideas for video games, action figures and the like. Let’s be honest, who hasn’t thought about what powers they would like to have? There is escapism involved.

I enjoyed your discussion about the resurgence of comic books after the Cold War. In particular, you discuss Captain America v. the Punisher. How do these two characters embody different parts of American culture, and how were they used in comics to do so?

Cap and the Punisher have been the two aspects of US policy. One, Cap, abides by the moral rules and strives to instill patriotism in others. The Punisher is a man who is driven by the same morality, but doesn’t want the niceties of “civilized war.” Cap never seems to be vicious with his enemies, at least not in the modern sense. Punisher is often frustrated by those limitations. To put it into a very contemporary context, think of it as the discussion of enhanced interrogation techniques. We pride ourselves as Americans as not stooping to the level of our enemies by torturing others for information. Our enemies are not bound by such restrictions. The Punisher is the embodiment of the “ends justify the means.” That said, both characters have had their conversions of sorts, especially when it comes to storylines like Civil War.

If my count is correct, I believe we are somewhere around the 43rd Marvel movie following the release of Deadpool. And really, the majority of movies were made after 2000. Now Marvel is getting ready to release Civil War. But what movie would you want to see them make out of a comic book character that they haven’t yet, and what story line would you want to see?

This is a hard one, as most of the comic book characters I like have been done, although not always well. I would like to see a good adaptation of the Punisher. I recently worked on a book Marvel Comics into Film (McFarland Publishing, 2016) and wrote on the Punisher films. The last film with Ray Stephenson as Punisher came close but still failed in some regards. As for overall characters, I would like to see the Unknown Soldier or Sgt. Rock in a movie version, but only if the writing is good.

As I mentioned, Civil War is getting ready to hit theaters soon. And you talk about Civil War in your book. What made this “maxi-series,” as you call it, so fascinating to comic book fans?

The maxi-series was several comic books that were tied in to an overall arc. The story line was on the overall abuse of power (and superpowers) after a terrorist attack. The plot eventually put Cap and Iron Man on opposite sides of the freedom versus security debate. The creators of the series often noted that this was a way to deal with the real aspects of the fight over the PATRIOT ACT and its intrusion on American society. No one is ever right or wrong on these things but clearly when emotions are riled a lot of decisions can be made that seem good at first, but are dangerous in the cold light of day. Marvel eventually combined the various comics into TPB (trade paperbacks) that allowed everyone like me to read them without having to read each comic individually.

The story also had former villains fighting on the side of right and wrong. A variation of the old adage “an enemy of an enemy is my friend.” So that further complicated issues. Punisher could never see how anyone could work with criminals. In the story lines, the most interesting story is that of Spiderman who goes from one side to the other as he starts to realize that things at first glance are not all that wonderful under the new system of control. Since Spidey is a teenager, it also played into the fact that there is a bit more emotion and less rationality in the decision making process.

Recently, as you probably know, Marvel released a new Black Panther graphic novel. It was written by National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates and drawn by artist Brian Stelfreeze. It sold big. Something like 300,000 copies. How important is the author to artist relationship in the quality of a book? What writer/artist teams in your opinion are the perfect team in the history of comic books and conflict?

I think that there is a very important correlation between the writers and artists. Black Panther is another important character to Marvel. To be honest I have not seen the new GN. The right combination has great impact. One take on Captain America which I found really interesting in idea but lacking in execution was Kyle Bakers take, Captain America: Red White and Black (2003). It noted that the Super-soldier program that created Cap was originally part of the Tuskegee Experiment, and that the first test cases were black. Unfortunately the artistic style was a detriment to me. Some folks hated it as it was too political or too much of a variation of the theme. For war comics, I would say Garth Ennis and Carlos Esquerra have done some outstanding work on several serious and satirical series. War Stories is what comes immediately to mind. Joe Kubert and Bob Kannigher were good for the old Sgt. Rock, GI Combat and Enemy Ace comics from DC. Jack Kirby and Joe Simon were great not only for Cap, but also the Boy Commandos, and even Front Line. I would say that the best overall teams were from EC when they did the Frontline Combat, Two Fisted Tales and related series in the 1950s. Archie Goodwin did some memorable stuff for Blazing Combat in the 1960s but overall currently it centers most on Garth Ennis as a writer.

Here’s a hypothetical. Let’s say I’m interested in reading comics but I haven’t picked one up in a long time. I’m in the military. And let’s say I haven’t been in a comic book store in ages. Once I enter a comic book store I realize I’m surrounded by cardboard boxes and lots of plastic. So…if I want to buy a few comics that deal with serious themes – like loss, leadership, justice, sacrifice, history – where do I begin? What questions should I ask?

Man, that’s an interesting question. I suppose it would depend on what genre one is looking for. If one wants pure war stories, I would go with War Stories. Living here currently in Seoul (I teach for UMUC to military personnel) there are TPBs of War Stories on sale in the BX. The military has embraced certain aspects of the role of comics. Marvel does an AAFES (Army-Air Force exchange system) comic book give away every year at PXs. The Navy did a graphic novel that dealt with the role of medics and corpsman in The Docs. Ernie Colon and Sid Jacobson did a comic for Military OneSource on the readjustment to life in the States and on PTSD, entitled Coming Home. I would say ask the clerks if they have any suggestions. There is such an industry behind it now that there is also the monthly trade catalog that features upcoming titles. Mostly I just look and try to find what looks interesting to me. If one gets an interest in war or military comics, then they could peruse the back issues but this can get pricey, especially if one wants to start getting into the series. I would also suggest looking first at the libraries. The Graphic Novels section in any library has a lot of titles that are TPB, GN or other bound compilations. It was how I started some of my work on Civil War. Then finally one could purchase Comics and Conflict, and then harangue the author for suggestions (HAHAHA).

The Atlantic magazine recently published an interesting piece about comic books and “The Canon.” Simply, people get really grouchy when directors and writers start messing with the facts about comic book characters’ backgrounds, their history. As the author says, this frustration, this sense of ownership by fans, it’s born out of love. Which I believe. But what are your thoughts on this? From your study, have comic book characters simply, in many instances, been reinvented, that they do change over time? That there is really no one way to see a character?

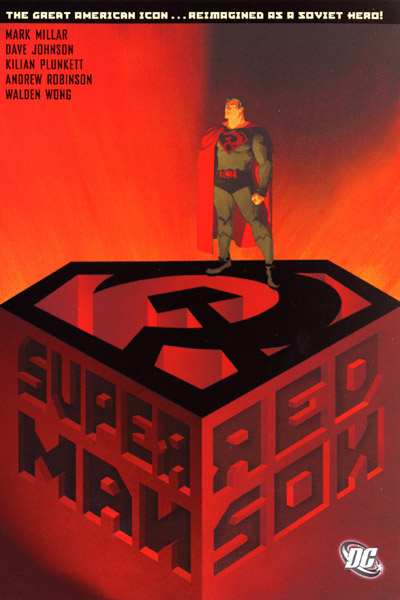

This is always a source of contention for purists. For example, I personally loved the take on Nick Fury as portrayed by Samuel L. Jackson. But because he was originally white (started out as a Kirby and Simon creation – Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos), some hated this version. I can understand some fans wanting to stick with the original formula but if it’s done well, it can be interesting. If it’s not done well, then I get mad like everyone else. I have read some interesting takes on characters. I loved the re-envisioning of Superman in Superman: Red Son, written by Mark Millar for example. The premise was that Superman landed not in Kansas in 1938, but hit in the Ukraine. The new Superman had a hammer and sickle in lieu of the “S”. Now I’m not a communist but I thought that the story line was interesting. However, some fans wrote in and were furious that he could take an American icon (he’s Scottish, by the way) and bastardize it. I actually remembered reading the original Superman #300 storyline that Millar premised the newer update on. Cap’s reinvention, Iron Man’s transformation to War Machine or Iron Patriot were also takes on this. Comic books, like the movies often have different writers and artists over the years. Everyone wants their own take on the character. Then again, I don’t always agree with how things turn out.

Why do you think so many people buy tickets to see a blockbuster film starring a comic book character, yet they wouldn’t be caught dead in a line at Barnes and Noble with a new copy of Doctor Strange? There seems to be, still, a cloud that hangs over comics, that these are children’s books. Is this true? Has this always been the case?

This has been an issue for a lot of folks. Comic books were born in a time in American history when there were not as many outlets for folks. As the original comics were simply re-published Sunday cartoon sections, they were seen primarily for kids. This didn’t mean that adults didn’t read comics as well. During WWII, the average age of a reader was pre-teens, 12 I think. But by the 1960s the readership went up a bit, and so some enterprising companies started to write stories to appeal to teen readers. This was why Spiderman was such a hit: he was a teen like his reader base.

By the early 2000s the average age of a comic book reader is in its early 20s. More money to burn on comics, but in return they expect more: more violence more language and even more of aspects towards sex. So some folks who walk into a comic book store and expect to read simple wholesome comics may be surprised or shocked. The creators and companies have evolved. The idea that the comic book collection will be the next gold mine is also a bit of a bust. Yes you may see a mint condition Amazing Fantasy #16 (first appearance of Spiderman) go for $600,000 or an Action Comics #1 (first appearance of Superman) go for $1.5 million but for those rarities, most are not worth the vast amount of money that people thought at one time. For me, it was simply using the material to look at aspects of history from a cultural base. I find the stuff incredible and adapted to other fields, like military training.

In your book, you talk a lot about how comics take sides – many were pro-war and many were anti-war. Do you think comics tend to be pro-war or anti-war? Or have they reached a point where they really can tackle the nuances of conflict?

Overall I think that war comics, especially the more recent ones, tend to be anti-war at their core. There have been some that were all heroics, and fantasy (Charleton was a great example of war fantasy) but overall, most of the stories have tried to say that there is always a cost of combat. Even though Sgt. Rock was seen as a fantasy of combat, and some Vietnam troops said that they wanted to enact heroics like those they had read a few years before, even Kubert tried to address the real nature of war and its stresses and violence. Again, I think that the best examples of war comics with a message were those from EC comics in the 1950s. This is the company that made MAD Magazine. Frontline Combat and Two Fisted Tales were written by WWII vets, and many of the stories had a cynicism to it. Some of the stories even tried to dispel the image of combat in film. I am reminded of one story from Two-Fisted Tales entitled “Corpse on the Imjin.” The story is told in a second person format, and describes in detail the concept of a soldier engaged in hand to hand combat. The book is shocking in an era when the comics were still VERY patriotic. This story had the reader (“You feel the breath go out of him as you hold him underwater”) active in the story. It also dealt with the very topical issue of the Korean War, not the exploits of WWII, where the “enemy” was more clear-cut. As I was by the Imjin River last weekend, I couldn’t help but think of that storyline. There are a lot of current comics that deal with the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. There are even graphic novels in other languages that tell of their experiences. I have one in German called Smile and Wave. But the confusion, the frustration and the war experience are not simply good guy wins, bad guy gets his, but it’s one of more layers. I think that comics like that are the best, the most real.

Professor Scott, thank you so much for your time.

Cord A. Scott has a Doctorate in American History from Loyola University Chicago and currently serves as a Traveling Collegiate Faculty for the UMUC-Asia. He is the author of Comics and Conflict: Patriotism and Propaganda from World War II through Operation Iraqi Freedom, published by the US Naval Institute Press. He has written for several encyclopedias, academic journals such as the International Journal of Comic Art, the Journal of Popular Culture, the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, and in several books on aspects of cultural history.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is a regular contributor to the Center for International Maritime Security. He is currently stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The comments and opinions above are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.