By LtCol James M. Jackson

Introduction

In 2027, Task Force Blade, a U.S. Naval (USN) task force in the Western Pacific, attempts to neutralize a People’s Liberation Army – Navy (PLAN) force through Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO). By dispersing its Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, Littoral Combat Ships, and Virginia-class submarines across the Philippine Sea and strategic chokepoints, the task force aims to enhance its elusiveness, resilience, and lethality. However, the limitations of this approach become apparent when confronted with the unique challenges posed by the vast Western Pacific theater and PLAN forces.

The operation begins with intelligence gathering using RQ-4 Global Hawk drones, P-8A Poseidon aircraft, and NRO satellites. Despite the advanced sensors, the PLAN’s use of electromagnetic spectrum management and deception techniques hinders the effectiveness of this intelligence gathering. These remote sensors struggle to gather and communicate targeting information to shooting platforms, and their lack of riskworthiness prevents them from gathering better information by gaining closer proximity to targets. Attack platforms, such as the U.S. destroyers, are subsequently compelled to break from their distributed operating posture to gain closer proximity to targets in order to gather targeting information with their organic sensors. These warships then attempt to coordinate a long-range missile attack using a combination of weapons such as Tomahawks and Standard Missile-6s (SM-6s).1 The SAG also coordinates with aircraft to launch Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASMs) against the PLAN forces.

But the process of compromising the distributed operating posture gave the PLA enough notice to put its platforms into a higher state of readiness, optimize its disposition against the probable threat axis, and surge several squadrons worth of aircraft to cover the warships. This forewarned and reinforced air defense network posed by the PLAN’s advanced warships and aircraft counters the comprehensive missile attack launched by U.S. forces. The need to break the distributed force posture to gain proximity to PLA forces drew U.S. forces deeper into the PLA weapons engagement zone, setting the stage for multiple rounds of counterattacks by PLA forces. The U.S. missile attack created signatures that clarified the sensing challenge for PLA forces, creating pressure for the now-targetable U.S. forces to concentrate into conventional formations to improve survivability. The limited magazine capacity of U.S. ships and logistical challenges limit the task force’s ability to sustain combat operations as it considers whether it can persist inside the WEZ.

Though this is only a vignette, it exposes significant limitations in the USN’s current approach to DMO when applied to the Western Pacific. Current distributed operating concepts must address these vast distances, complex environment, and the PLA’s anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities. The U.S. Navy can address some key challenges inherent in executing DMO against the PLA in the Western Pacific by incorporating lessons from Ukraine’s advanced scouting and targeting, asymmetric tactics, and establishment of sea denial zones in the Black Sea. Ukrainian actions can inform a novel framework for how a distributed U.S. maritime force can overcome the operational challenges and asymmetric disadvantages it will face against the PLA in the Western Pacific.

DMO – Defining the Concept

The most current and official definition of DMO is in the 2020 Tri-Service Maritime document “Advantage at Sea.” Accordingly, “Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) is an operating concept that focuses on the distribution, integration, and maneuvering of naval forces to mass overwhelming combat power and effects at chosen times and locations.”2 Furthermore, the “Fighting DMO” series on CIMSE notes several common themes in public definitions of DMO, including “the massing and convergence of fires from distributed forces, complicating adversary targeting and decision-making, and networking effects across platforms and domains.”3 Others have noted that the “denial of enemy intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities is essential to DMO,” and that the force must be “hard to find, hard to kill, and lethal.”4,5 These definitions can be synthesized to define DMO as the following:

The distribution and maneuver of naval forces across various domains, blending sea-based and land-based capabilities to effectively concentrate combat power and hinder adversary targeting while emphasizing the dispersion of units, diversified use of sensors and weapons, and incorporation of long-range and autonomous systems.

DMO signifies a strategic evolution from traditional platform-centric warfare to a network-centric paradigm.6 This approach enables massing firepower without co-locating launch platforms, facilitated by increased weapons range and networks for long-range coordination. It seeks to garner the advantages of concentration – a massive, unified strike force – without the associated risks of grouping assets too closely. DMO emphasizes a dispersed yet cohesive operational pattern, aiming to create a formidable force without centralizing targets for the adversary.

DMO synthesizes the principles of distribution, integration, and maneuver to mass combat power effectively and is a response to specific challenges posed by the PLA’s sophisticated naval capabilities.7 The PLA maintains a highly capable anti-ship missile arsenal, including advanced weapons like the DF-21D and DF-26 missiles, which can target U.S. carriers and major surface combatants over long distances.8 The concept seeks to mitigate these threats by dispersing naval forces across a broader area. By employing DMO, the U.S. Navy aims to enhance its survivability in environments dominated by long-range missile threats and maintain its ability to project power despite an increasingly contested maritime domain.

Critical PLA challenges to DMO

The PLA’s sophisticated detection abilities, advanced missile ranges, and mass firepower strategies will challenge a distributed maritime force’s attempts at being elusive, resilient, and lethal. The PLA’s advanced ISR and detection capabilities include a vast network of land-based radars, over-the-horizon (OTH) radars, and a constellation of reconnaissance satellites. Maintaining resilience will prove challenging as the PLA’s long-range precision strike missiles, such as the DF-21D and DF-26 “carrier killer” missiles, target U.S. naval assets from long ranges. The PLA’s massed firepower strategies, particularly their saturation missile attacks, can overwhelm a distributed force’s defenses and deplete its magazine depth, effectively neutralizing its offensive capacity and ability to strike effectively first.

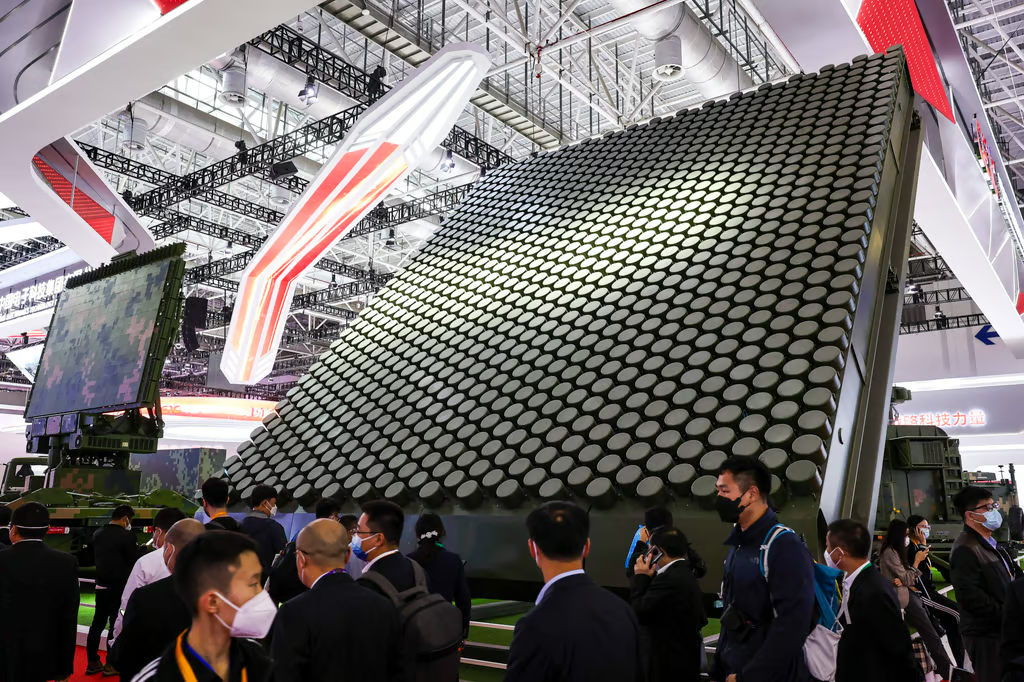

The PLA can nearly relentlessly detect and track naval assets across enormous distances. Their land-based radar systems, such as the JY-27A and YLC-8B, provide long-range surveillance coverage extending hundreds of kilometers from the Chinese mainland.9 Additionally, the PLA’s OTH radars, like the SLC-7 and SLC-18, exploit ionospheric reflection to detect surface targets up to 3,000 km away.10 Furthermore, China’s growing fleet of Yaogan and Gaofen series satellites equipped with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors enable all-weather, day-and-night monitoring of maritime activities.11 These advanced ISR assets, working in concert, severely undermine a distributed force’s fundamental intent to remain elusive. Maintaining operational effectiveness under DMO will require an increased focus on advanced stealth technologies, improved evasion tactics, and robust counter-surveillance measures.12 Adapting to this threat environment is critical for the U.S. Navy to counteract the sophisticated surveillance methods of the PLA effectively.

The PLA’s advanced missile capabilities, including weapons like the DF-21D and DF-26 “carrier killer” missiles, present significant challenges to distributed operations. These missiles can target U.S. naval assets from 1,500 miles and pose a severe threat to carriers and other large vessels.13 The DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle, with a range of up to 1,500 miles, further complicates this, as its maneuverability and speed present additional tracking and interception challenges.14 Moreover, the PLA’s continued development of the YJ-18 and YJ-21 anti-ship cruise missiles, with ranges exceeding 330 miles and 900 miles, respectively, adds another layer of complexity to the threat environment. These missiles, capable of being launched from various platforms such as submarines, ships, and aircraft, can saturate and overwhelm a distributed force’s defenses.15 The PLA’s investment in the H-6K bomber, which can carry up to six YJ-12 supersonic anti-ship missiles, further extends the reach and flexibility of their strike capabilities.16

Using massed, multi-axis missile attacks can achieve rapid dominance in a conflict. This approach exploits the finite nature of U.S. naval missile defense systems, such as the Aegis Combat System and Standard Missile interceptors. By launching a mass quantity of missiles from various platforms, including land-based launchers, ships, submarines, and aircraft, the PLA can saturate and exhaust these defensive capabilities.17 Such a depletion would effectively neutralize a distributed force’s (or platform’s) capacity before it can launch its own attacks.18 The affected force will have lost its ability to strike effectively first.19

The actions conducted by Ukraine against the Russian Black Sea Fleet (BSF) illuminate a way to resolve these challenges. The success of Ukraine in countering Russian aggression offers valuable lessons to address the PLA challenges of sophisticated ISR networks, long-range precision strike missiles, and massed firepower strategies. By incorporating key components of Ukraine’s approach, such as the use of mobile and shore-based anti-ship missiles, the employment of unmanned systems for ISR and strike missions, and the adoption of unconventional tactics like the “mosquito fleet” concept, the USN can develop a more resilient and effective distributed force posture. An evolved DMO framework, which emphasizes increased mobility, flexibility, and the integration of novel technologies and tactics, can help mitigate the risks posed by the PLA’s advanced capabilities and provide a more robust deterrent in the region. Nonetheless, adapting to this evolving threat landscape will require continuous innovation, experimentation, and a willingness to challenge traditional paradigms of naval warfare.

Ukraine in the Black Sea

Ukraine’s Black Sea operations demonstrate a potent combination of advanced scouting and targeting, unconventional tactics, and the establishment of sea denial zones. Through enhanced surveillance using drones like the Bayraktar TB2, Ukraine executed precision strikes on key targets, such as the sinking of the Russian cruiser Moskva.20 Ukraine complements this advanced scouting with asymmetric tactics, including employing mines, UUVs, shore-based anti-ship missiles, and small, fast-attack craft known as the “mosquito fleet.”21 By integrating these elements with innovative surface maneuvers, Ukraine disrupts traditional approaches to naval engagements, achieving stealth and effectiveness in striking first.

The culmination of these approaches is the establishment of sea denial zones, where Ukraine effectively restricts adversary access and transforms maritime spaces into formidable defensive lines.22 These measures limit enemy movement and provide a powerful deterrent against aggressive naval actions. Adapting and applying these lessons to the DMO concept can help mitigate the risks posed by the PLA’s advanced capabilities and enhance the resilience and effectiveness of U.S. naval forces in the Western Pacific.

Ukraine has effectively employed advanced scouting techniques in the Black Sea to enhance its ability to strike Russian naval assets first. The use of aerial surveillance drones, such as the Bayraktar TB2, has provided remote situational awareness deep inside the adversary weapons engagement zone and targeted precision engagements, as demonstrated by the tracking and targeting of Raptor-class patrol boats.23 The sinking of the Moskva cruiser was achieved through precise intelligence that cued Neptune missile launches, highlighting Ukraine’s capacity to execute high-impact strikes by leveraging a rapid intelligence-gathering and targeting cycle. Ukraine’s comprehensive scouting methodology also incorporates penetrating UAVs and UUVs for intelligence-gathering missions against various targets, including the minesweeper Ivan Golubets and the cruiser Admiral Makarov.24 These successes showcase Ukraine’s effective integration of reconnaissance, scouting, and ISR capabilities to target Russian BSF operations. By combining advanced technologies, riskworthy scouts, and streamlined intelligence analysis and decision-making processes, Ukraine has established an effective model for conducting maritime surveillance and targeting in a contested environment. The USN can use similar scouting concepts to gain an advantage in the Western Pacific.

Ukraine’s Black Sea naval operations have uniquely applied unconventional tactics, leveraging advanced technologies and innovation to counter Russian aggression. The employment of Bayraktar TB2 drones for precision strikes against Russian Raptor-class patrol boats and a BK-16 high-speed assault boat near Snake Island represents an unconventional use of aerial drones in a maritime context, allowing Ukraine to challenge Russia’s naval superiority while minimizing risk to Ukrainian forces.25

Similarly, the deployment of MAGURA V5 USVs to successfully attack larger Russian vessels, such as the Project 22160 patrol ship Sergey Kotov and the Tarantul-class corvette R-334 Ivanovets, represents a departure from traditional naval conflict, as these small, agile, and expendable platforms can swarm and overwhelm enemy defenses.26 These unconventional approaches, further enhanced by the integration of cyber warfare capabilities and special forces operations, as exemplified by the joint Ukrainian SBU and Navy effort that seriously damaged the Ropucha-class landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak near the Port of Novorossiysk, have allowed a smaller, less powerful naval force to effectively challenge a larger adversary.27

2027 Revisited: TF Blade in the South China Sea

TF Blade, operating in the South China Sea, adopts a form of Ukraine’s advanced scouting and targeting tactics to counter a PLA naval threat. The task force, composed of Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, Littoral Combat Ships, and USVs, detects a PLAN SAG near the Spratly Islands using a network of MQ-9B SeaGuardian UAVs and Orca UUVs.28 The SeaGuardians provide persistent, high-resolution imagery of the PLA SAG, which includes a Type 055 Renhai-class cruiser and several Type 052D Luyang III-class destroyers. At the same time, the Orca UUVs gather acoustic intelligence on the PLA ships, identifying their unique sound signatures and tracking their movements. Fusing the data from these penetrating scouting platforms, the task force’s AI-enabled battle management system generates a comprehensive, real-time picture of the PLA SAG’s disposition and vulnerabilities, revealing that the Type 055 cruiser, a critical command and control node, is operating with degraded air defense capabilities.

In 2027, TF Blade seizes the opportunity, launching a coordinated, multi-domain strike against the PLA SAG. A swarm of USVs deploy electronic warfare payloads to jam the PLA ships’ sensors and communications while emitting deceptive signatures. At the same time, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers are able to launch a salvo of SM-6 missiles from widely distributed firing positions. These missiles, guided by the targeting data from the SeaGuardians and Orcas, converge on the Type 055 cruiser, overwhelming its weakened defenses and neutralizing the ship with multiple hits. This strike’s precision and coordination considerably weakens the PLA SAG, forcing it to withdraw from the area and reassess its strategy.

Following the successful strike against the PLA Surface Action Group (SAG) near the Spratly Islands, TF Blade continues to monitor the situation using its advanced scouting and targeting capabilities. The task force launches a series of asymmetric attacks to further disrupt PLA operations and degrade their combat capabilities. A Zumwalt-class destroyer employs its stealth to gain proximity to a PLA amphibious group and deploys a swarm of small, expendable USVs to conduct a coordinated attack on a PLA Type 071 transport dock. These USVs, armed with miniaturized torpedoes and guided missiles, evade PLA defenses and deliver a compromising strike on the vessel by significantly damaging its well deck.

TF Blade’s CSG and its associated Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) establish a sea denial zone against the PLA Navy in the Western Pacific. By deploying a network of MQ-4C Triton drones for high-altitude surveillance, supplemented by satellite reconnaissance, the CSG and DESRON effectively track critical PLA assets, including Type 055 destroyers operating near the Paracel Islands, and monitor their movements toward the first island chain. Another layer of close-in penetrating scouts and drones is situated in higher-risk areas to gain high quality targeting information that can be relayed back through the Tritons to cue standoff engagements from distributed forces.

TF Blade positions its penetrating UUVs near the Spratly Islands to further restrict PLA naval operations while laying sensor-laden smart mines to control crucial sea lanes and chokepoints. These UUVs discreetly monitor PLA submarine activity, particularly the movements of their Type 093 and Type 039 classes, providing real-time intelligence on their positions and patrol patterns. Leveraging this intelligence, Arleigh Burke-class destroyers distribute themselves into firing positions outside PLA submarine patrol boxes, launching Tomahawk strikes against PLA command and control centers on Mischief Reef and Subi Reef, damaging their A2/AD network.

These actions challenge and reshape PLA’s traditional maritime strategies, imposing significant operational constraints on their naval forces and pushing their effective range further back from critical areas like the Taiwan Strait. Through this multi-domain approach, the CSG and DESRON establish a robust sea denial zone in the Western Pacific.

Logistical and Sustainment Challenges in Extended Maritime Operations

Applying Ukrainian Black Sea tactics against the PLA in the Western Pacific presents significant logistical challenges due to the region’s vast distances and the USN’s need to maintain long supply lines. Unlike Ukraine’s operations in the Black Sea, which benefit from close proximity to land-based support, the U.S. Navy would need to sustain operations up to 6,000 nautical miles from its main bases in the continental United States. The PLAN, in contrast, enjoys a logistical advantage with its interior lines of communication and access to numerous bases along the Chinese coast, the furthest being only 1,500 nautical miles from the potential areas of operation in the South China Sea.

The USN must establish a robust network of forward operating bases, pre-positioned supplies, and mobile logistics platforms to overcome these challenges and effectively implement DMO tactics informed by the Ukrainian experience. This would require significant investment in logistics infrastructure, such as increasing the number of support ships from the current 29 to an estimated 60-70, as the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments recommended.29 Additionally, the USN would need to expand its access to facilities in allied countries, such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, and develop new technologies to extend the range and endurance of its platforms, particularly unmanned vehicles. For instance, the U.S. Navy’s current MQ-4C Triton drone has a range of 8,200 nautical miles, but operating in the Western Pacific may require even more extended endurance capabilities.30

Conducting DMO using Ukrainian concepts will require making logistics more distributed, with smaller depots that are less targetable. This will increase the redundancy of the logistics network where no logistics node is so critical that its loss severely impacts the broader force. Techniques employed by Ukraine, such as the use of diversified, smaller platforms, can be scaled up and supported by the USN’s advanced logistical capabilities, enabling sustained operations even in the extended operational areas of the Western Pacific. Smaller, higher quantities of capabilities would require fewer exquisite capabilities, allowing for the use of numerous smaller ports and airfields that may not be accessible to the USN’s large ships. Utilizing more yet smaller logistics nodes throughout the theater would improve logistics resiliency and flexibility.

Differences in Maritime Theater Characteristics

The operational environments of the Black Sea and the Western Pacific differ significantly, presenting unique challenges in applying Ukrainian naval tactics against the PLA Navy. The Black Sea is a relatively confined body of water with a maximum width of 600 nautical miles. In contrast, the Western Pacific is a vast expanse of ocean, with the potential area of operations spanning thousands of nautical miles from the South China Sea to the Philippine Sea. These differences in scale and geography substantially impact the effectiveness of various naval tactics and technologies, and the viability of applying Ukrainian lessons to the Pacific theater.

The Black Sea’s confined nature allows for the effective use of smaller, more agile craft and the deployment of dense networks of sensors and mines to control key chokepoints. These tactics may be less effective in the vastness of the Western Pacific, as the PLAN has greater room for maneuver and can leverage its larger, more capable ships to project power over greater distances. Ukraine’s successful use of shore-based anti-ship missiles, such as the Neptune, and drones, like the Bayraktar TB2, similarly rely heavily on the Black Sea’s limited distances and the ability to integrate land-based support. However, more extended detection and engagement ranges, as well as the limited availability of land-based support infrastructure, may reduce the effectiveness of these systems in the open ocean environment of the Western Pacific. Adapting Ukrainian tactics to this theater would require significant investment in developing long-range platforms, such as larger USVs and UUVs, as well as enhancing existing systems to extend their reach and endurance.

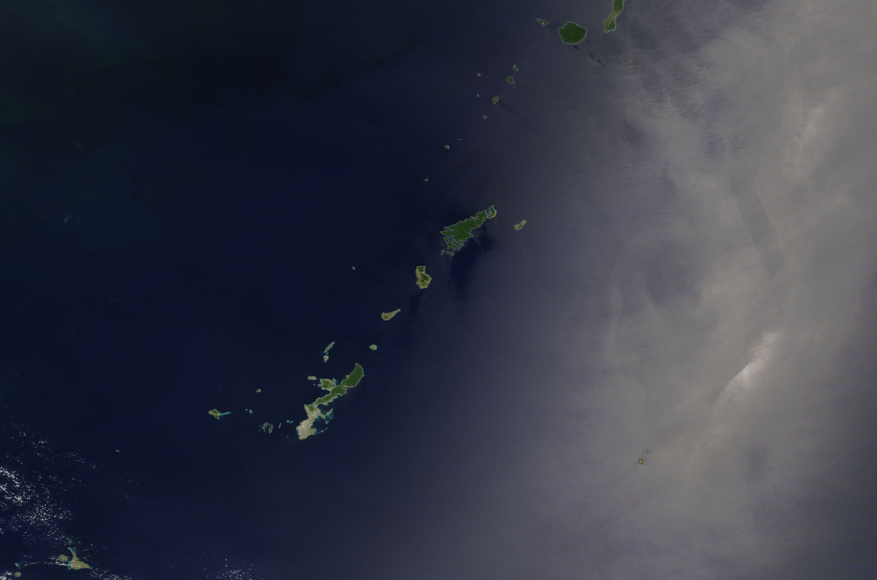

While the Black Sea’s confined nature allows for the use of dense networks of sensors and mines to control key chokepoints, the USN can still adopt this approach in critical areas of the Western Pacific. These include critical maritime chokepoints like the Taiwan Strait, Philippine Strait, the Ryukus Island chain, and the littorals in the South China Sea. In these areas, the USN could create localized sea denial zones informed by the Ukrainian experience. By adapting these tactics and technologies to the unique geography of the Western Pacific, such as focusing on strategic chokepoints and key archipelagic terrain, the USN can effectively apply the lessons learned from Ukraine’s Black Sea operations to counter the PLAN, despite the differences in the scale and characteristics of the operational environments.

Recommendations

For the USN to better implement these tactics, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) should sponsor studies to explore the optimal integration of penetrating and riskworthy USVs and UUVs into the DMO concept, focusing on their roles in ISR, EW, and offensive operations. These studies should specifically investigate the most effective USV/UUV platforms and payloads for specific missions, command and control architectures for coordinating drone swarms, USV/UUV facilitation of distributed killchains, tactics for employing drone swarms in littoral environments, and countermeasures against adversary drone threats.

The USN should develop and test asymmetric warfare tactics inspired by Ukrainian operations. These should focus on the coordination of USV/UUV swarm attacks on enemy surface combatants, the integration of cyber and EW capabilities to degrade enemy C4ISR networks, the employment of mines and coastal defense systems to establish localized sea denial zones, and the use of small, agile units for amphibious raids and seizure of key maritime terrain. The integration of these tactics should be refined through wargaming, simulations, and live exercises, such as the Navy’s Large Scale Exercise (LSE), to validate their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

The USN should prioritize developing and integrating a system similar to Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) with USVs and UUVs to enhance the situational awareness and distributed lethality of conventional naval forces.31 Key focus areas should include the AI-driven autonomous coordination systems for human-machine teams, advanced communication and data-sharing technologies for secure and reliable connectivity, and the integration of collaborative combat systems with other maritime assets operating in a distributed manner. These systems should undergo rigorous testing in realistic A2/AD environments to ensure reliability in a contested electromagnetic spectrum.

The USN should also explore ways to integrate DMO with Marine Stand-In Forces (SIF) and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO).32 These efforts should focus on developing rapidly deployable, self-sustaining EABO units that can provide ISR and targeting support to distributed naval forces. Additionally, the Navy should explore the employment of SIF using USVs, UUVs, and coastal defense systems to create localized sea denial zones.33 To seize and defend critical maritime terrain in contested environments, coordination between DMO and SIF/EABO assets should be a key priority. Finally, these experiments and exercises should refine tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) for integrated DMO-SIF/EABO operations, ensuring a cohesive and practical approach to distributed maritime warfare.

Finally, the USN should establish and codify clear DMO doctrine, and it should evaluate the proficiency of naval formations at executing this doctrine during their certification cycles. Simultaneously, the Navy should create a dedicated warfighting development organization to lead, coordinate, and prioritize DMO-related efforts across the Navy and Marine Corps. It should develop and maintain a repository of lessons learned and best practices from DMO exercises and operations, provide training and education to Navy and Marine Corps personnel on DMO concepts and tactics, and foster collaboration with allies, partners, and industry to advance DMO capabilities and interoperability. By taking these steps, the U.S. Navy can create a comprehensive framework for the successful implementation and continuous improvement of DMO, ensuring its forces are well-prepared to operate effectively in contested environments and counter the evolving threats posed by near-peer adversaries.

Conclusion

Ukraine has demonstrated the value of exploiting vulnerabilities in Russian naval operations with asymmetric capabilities. These methods have effectively pushed Russian naval forces away from the western Black Sea and forced them to operate primarily near their bases in Crimea and Novorossiysk. This forfeiture of sea control has found Russia largely confining its naval forces to defensive positions with limited ability to project power or support land-based operations in southern Ukraine. Despite the significant disparity in maritime strength and the loss of a substantial portion of its fleet early in the conflict, Ukraine’s innovative approach to sea denial, centered on penetrative scouting, precision targeting, and asymmetric capabilities, has allowed it to effectively dispute Russia’s sea control in the Black Sea coastal waters, significantly undermining its strategic position in the region.34 While the lessons learned from Ukraine’s Black Sea operations provide valuable insights, their direct application to the Western Pacific requires careful consideration of this vast and complex theater’s unique geographical and operational challenges.

By analyzing the theoretical underpinnings of DMO, the practical challenges in the Western Pacific, and Ukrainian actions against the Russian Black Sea Fleet, a framework can be developed that directly addresses the challenges of a distributed force facing the PLA. Despite the difference in operational environments, the fundamental principles and tactics employed by Ukraine in the Black Sea can be adapted and applied to counter the PLAN in the Western Pacific. The USN can enhance the effectiveness of DMO by focusing on advanced scouting, asymmetric tactics, and the establishment of sea denial zones along key maritime terrain, as demonstrated by Ukraine’s success. This will not only broaden the applicability of DMO as an operational concept, but can also provide a tangible framework for addressing asymmetry in naval warfare.

LtCol James Jackson is a career logistician in the U.S. Marines. He is a graduate of the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School and is currently an Operational Planner at Marine Corps Forces Cyberspace Command.

References

[1] “Standard Missile-6 (SM-6),” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, accessed April 7, 2023, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/sm-6/.

[2] Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power, U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 25, December 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Dec/16/2002553074/-1/-1/0/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF.

[3] Dmitry Filipoff. “Fighting DMO, PT. 1: Defining Distributed Maritime Operations and The Future of Naval Warfare”. Center for International Maritime Security. Accessed March 8, 2024. https://cimsec.org/fighting-dmo-pt-1-defining-distributed-maritime-operations-and-the-future-of-naval-warfare/.

[4]Harlan Ullman. “Are There Flaws in the U.S. Navy’s Distributed Maritime Operations?,” Defense News, January 23, 2023. https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2023/01/23/are-there-flaws-in-the-us-navys-distributed-maritime-operations/.

[5] Richard Mosier. “Distributed Maritime Operations: Hard to Find,” Center for International Maritime Security. Accessed March 8, 2024. https://cimsec.org/distributed-maritime-operations-hard-to-find/.

[6] Dmitry Filipoff. “Fighting DMO, PT. 1: Defining Distributed Maritime Operations and The Future of Naval Warfare”. Center for International Maritime Security. Accessed March 8, 2024. https://cimsec.org/fighting-dmo-pt-1-defining-distributed-maritime-operations-and-the-future-of-naval-warfare

[7] Ibid.

[8] Dr. Sam Goldsmith, “VAMPIRE VAMPIRE VAMPIRE The PLA’s anti-ship cruise missile threat to Australian and allied naval operations,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, April 2022, 10.

[9] “Introduction to Chinese Military Radar,” GlobalSecurity.org, accessed March 12, 2024, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/radar-intro.htm.

[10] Ibid.

[11]James Andrew Lewis, ‘No Place to Hide: A Look at China’s Geosynchronous Surveillance Capabilities,’ Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), accessed March 20, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/no-place-hide-look-chinas-geosynchronous-surveillance-capabilities.

[12] Richard Mosier. “Distributed Maritime Operations: Hard to Find,” Center for International Maritime Security. Accessed March 8, 2024. https://cimsec.org/distributed-maritime-operations-hard-to-find/.

[13] “Missiles of China.” Missile Threat. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/.

[14] “Missiles of China.” Missile Threat. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/.

[15] “YJ-18,” Missile Threat, accessed March 24, 2024, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/yj-18/.

[16] Military Today, ‘H-6K Strategic Bomber,’ accessed March 20, 2024, https://www.militarytoday.com/aircraft/h6k.htm.

[17] “The Chinese Navy: Preparing for ‘Informatized’ War at Sea,” Office of Naval Intelligence, Suitland, MD, 2021, https://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2021_China_Informatized_War_at_Sea.pdf

[18] Dmitry Filipoff.”Fighting DMO Pt 4: Weapons Depletion and the Last Ditch Salvo Dynamic.” CIMSEC. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://cimsec.org/fighting-dmo-pt-4-weapons-depletion-and-the-last-ditch-salvo-dynamic/.

[19] Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and Robert P. Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, Third Edition (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 269. See Hughes’ concept of “striking effectively first”.

[20] H.I. Sutton, “Timeline-2022 Ukraine Invasion At Sea,” Accessed March 22, 2024, http://www.hisutton.com/Timeline-2022-Ukraine-Invasion-At-Sea.html.

[21] Ibid.

[22] USNI News. “Western Navies See Strategic, Tactical Lessons from Ukraine Invasion.” Accessed March 20, 2024. https://news.usni.org/2023/01/31/western-navies-see-strategic-tactical-lessons-from-ukraine-invasion.

[23] H.I. Sutton, “Timeline-2022 Ukraine Invasion At Sea,” Accessed March 22, 2024, http://www.hisutton.com/Timeline-2022-Ukraine-Invasion-At-Sea.html.

[24] Sutton, “Timeline-2022 Ukraine Invasion At Sea”.

[25] H.I. Sutton, “Timeline-2022 Ukraine Invasion At Sea,” Accessed March 22, 2024, http://www.hisutton.com/Timeline-2022-Ukraine-Invasion-At-Sea.html.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Naval News, “Boeing Delivers First Orca XLUUV to U.S. Navy,” Naval News, April 28, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/04/boeing-delivers-first-orca-xluuv-to-u-s-navy/

[29]Timothy A. Walton and Ryan Boone, “Sustaining the Fight: Resilient Maritime Logistics for a New Era,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2019, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/Resilient_Maritime_Logistics.pdf. Viii.

[30] “MQ-4C Triton Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS),” Naval Technology, accessed March 24, 2024, https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/mq-4c-triton-bams-uas-us/.

[31] “Air Force, Navy collaborating on 4 ‘fundamentals’ of CCA drones,” DefenseScoop, accessed 1 April 2024, https://www.defensescoop.com/air-force-navy-collaborating-on-4-fundamentals-of-cca-drones/

[32] United States Marine Corps, Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 2023), 1-2.

[33] U.S. Marine Corps, A Concept for Stand-in Forces (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 2021), 4.

[34] Vego, Milan (2015) “On Littoral Warfare,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 68: No. 2, Article 4. This paper utilizes Dr. Vego’s definition of sea control: “the ability to use a given part of the sea or ocean and associated airspace for military and nonmilitary purposes and deny the same to the enemy during open hostilities.”

Featured Image: A satellite photo appearing to show the damaged Russian landing vessel Olenegorsky Gornyak leaking oil while docked in Novorossiysk, Russia. Ukraine said its sea drones damaged the warship. (Photo by Planet Labs PBC via AP)