Introduction

The United States possesses the world’s leading military. It has the most sophisticated air, land, sea, and, now, cyber forces and wields them in such a manner such that no single nation, barring the employment of total nuclear war, approaches its destructive capability.

America’s military power in these realms is identifiable. Fighter jets, bombs, tanks, submarines, ships, and more — these are all synonymous with the Nation’s warfighting portfolio. And in the modern world, even though we cannot see a cyber attack coming, we can certainly see its results — as with the alleged Stuxnet attack on Iranian nuclear facilities. To the public, these tools together are America’s “stick” on the global stage, for whatever purpose its leaders deem necessary.

Space is different. There are no bombs raining from orbit, and no crack special forces deploying from orbital platforms. The tide of battle is never turned by the sudden appearance of a satellite overhead. In fact, no one in the history of war has ever been killed by a weapon from space. There are actually no weapons in space nor will there be any in the foreseeable future.

Yet, America is the world’s space power. The Nation’s strength in the modern military era is dependent on its space capabilities.

Yet, America is the world’s space power. The Nation’s strength in the modern military era is dependent on its space capabilities. Space is fundamentally different than air, sea, land, and cyber power, and at the same time inextricably tied to them. It buttresses, binds, and enhances all of those visible modes of power. America cannot conduct war without space.

Simply, space is inherently a medium, as with air, land, sea, and cyber, and space power is the ability to use or deny the use by others of that medium. The United States Air Force (USAF) defines military space power as a “capability” to utilize [space-based] assets towards fulfilling national security needs.[1] In this, space is similar to other forms of military projection. But, its difference comes in how it is measured. When viewed in this context, space power is thus the aggregate of a nation’s abilities to establish, access, and leverage its orbital assets to further all other forms of national power.

Big Brother is Watching

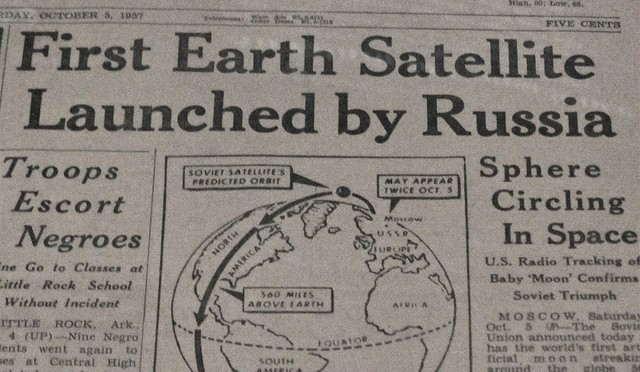

It is important to note that space power is inherently global, as dictated by orbital mechanics. It is essentially impossible to go to space without passing over another nation in some capacity. Thus, the concept of peaceful overflight was established with the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, when the United States did not protest the path of the satellite even as it passed over the Nation. This idea stands in contrast to traditional territorial rules in which it would be considered a violation of sovereignty to put a military craft on or above another nation without express permission.

This difference became especially obvious in 1960 when Francis Gary Powers was shot down in his U-2 spy aircraft above the Soviet Union. Prior to that, the U.S. recognized that its missions over Russia were certainly a provocation and against international norms, but felt that the U-2 aircraft were more than capable of evading Soviet ground-based interceptors. The imagery intelligence (IMINT), they thought, justified the risk.

The downing and subsequent capture of Powers was a significant embarrassment for the United States, and President Eisenhower immediately halted this practice. From that point forward, it became clear that the only viable way for the U.S. to gather substantial IMINT against an opponent with sophisticated anti-air capabilities was via satellite.

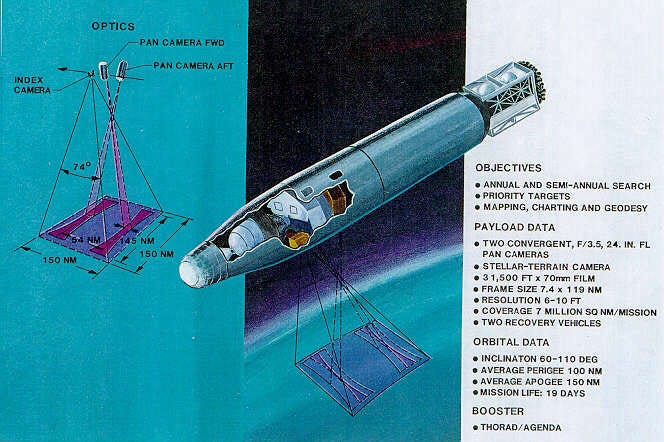

The best quantification of space power in its early days came just a few months after the Powers incident. The CIA-run Corona program produced the first successful IMINT satellite in history. This satellite, code-named Discoverer 14, obtained more photographs of the Soviet Union in just 17 orbits over the course of a day than all 24 of the previous U-2 flights combined. Electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellites, such as the early generation GRAB program (which actually launched before Corona), helped map Soviet air defenses by detecting radar pulses, which enabled strategic planners to map bomber routes. Although air-and-sea-based reconnaissance craft had the capability to also detect radar pulses, they could only identify targets at a maximum of 200 miles within the Soviet Union, far less than was needed to plan a secure route to interior targets. Space became more than just a one-to-one replacement of existing tools; it offered significantly more access to foes.

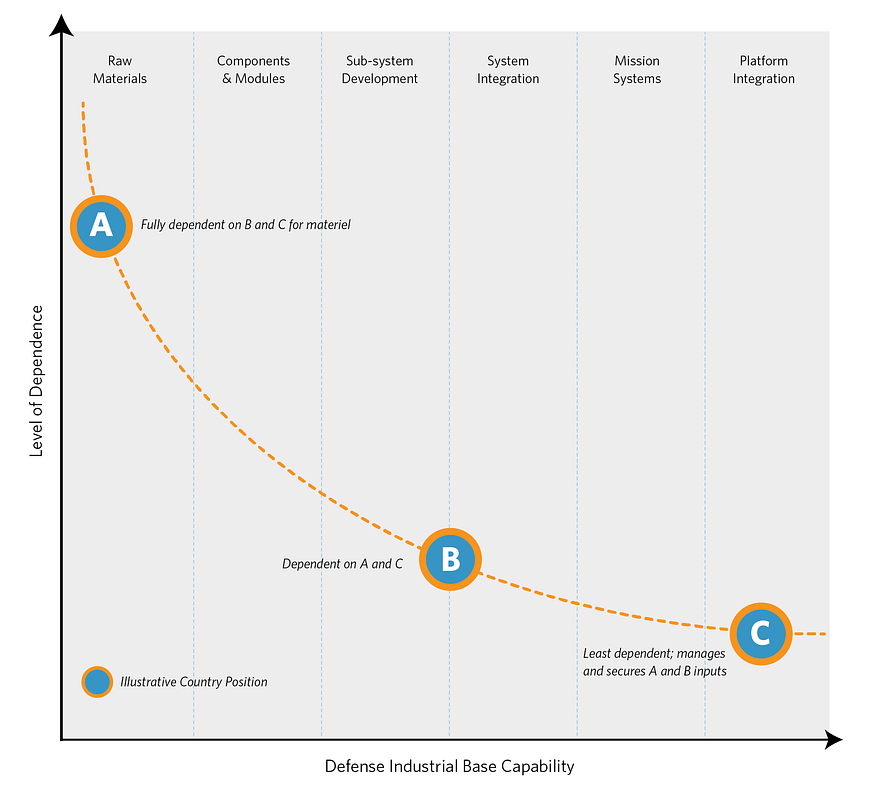

Superiority then became three-pronged: who had the broadest capabilities, who had the best technology in each form of space-based intelligence gathering, and who had the best coverage? Said another way, how well could a nation monitor all spectra in detail at all times everywhere that matters?

Nearly a decade after Corona transformed space into a viable form of power, the U.S. leveraged its first reliable weather monitoring and communications relay satellites in the Vietnam War. This expanded the role of space to that of an active component on the battlefield, rather than just a pre-conflict source of intelligence — an enormously important growth.

More than that, it represented a substantial evolution of war as a whole. The sudden enhancement of meteorological data due to dedicated satellites gave field commanders far greater clarity than in previous conflicts as to when would be the ideal windows to mount a strike or a longer campaign. This was especially important in Vietnam, which was often overcast.

The United States faces the greatest diversity of military threats in its history. At the same time, the military is undergoing a significant size reduction.

Satellite communications also made their wartime debut in Vietnam. This capability offered the first true live link between war planners and field commanders, for the conveyance of orders and the timely distribution of sensitive intelligence. Whereas intelligence satellites broadened the world by opening up vast new areas to prying eyes, communications satellites dramatically shrank it. However, this new channel was offered only to the top commanders in any region, due to limitations in infrastructure. Soldiers in the field still used radios to communicate with base.

All these space capabilities continued their evolutionary growth for the next few decades. But, it was Operation Desert Storm in 1990 and 1991 that marked space power as a revolutionary change in the conduct of war. Called the “first space war” by some, this conflict was the first time that satellite communications and new position, navigation, and timing (PNT) systems were utilized in direct concert with military forces to monitor and direct an ongoing campaign at all levels. Space-based intelligence-gathering satellites mapped Iraqi strategic installations well ahead of the first shots and continued to track changes in enemy force distribution. Satellite communications systems enabled ground forces to transmit targeting data to en-route aircraft, substantially improving the accuracy of dropped munitions. In addition, while the constellation was not yet fully deployed, the Global Positioning System (GPS) conveyed Coalition forces an enormous strategic advantage, by enabling ground forces to travel through previously unmapped territory and circumvent the heavily defended road system into Iraq.

Today

The United States faces the greatest diversity of military threats in its history. At the same time, the military is undergoing a significant size reduction. Yet, more so now than ever, it possesses the ability to strike anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice. It does not need to constantly maintain local forces when it has force projection. In the modern world, force projection would not exist without space power.

Special forces and drone operations have taken front stage in America’s Global War on Terror. IMINT and SIGINT satellites provide important intelligence about targets far below. GPS satellites enable drones to fly to areas of interest and, if necessary, guide their munitions to their final destinations with minimal collateral damage. Drone operators are often far away from the craft they are piloting, many times even in a different hemisphere. This capability is only possible by utilizing high throughput communications satellites. For special forces, GPS is used to get the teams quickly to their targets. Further, portable satellite communications units allow them to relay updates to their commanders and call in support if necessary.

These options are especially effective against non-space actors who do not have the capabilities to strike back. However, space is increasingly becoming “congested, contested, and competitive” — meaning a broader group of nations is doing more to leverage space for their own military power and deny others from doing the same. China stands out in this realm. While the nation (exclusive of nuclear weapons) stands no match against the United States in any conventional confrontation, it possesses counter-space technologies that would dramatically curtail America’s force projection strengths. In such a situation, America’s power abroad would decline dramatically, to such a point that along the Asian coasts, China may have local superiority.

As such, the definition of space power is expanding, to being the aggregate of a nation’s abilities to establish, access, leverage, and sustain its orbital assets to further all other forms of national power. Earth-shaking rocket launches aside, space is the silent partner in nearly American military endeavor today. Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom and the subsequent counterinsurgency operations that followed demonstrated that clearly enough. Space guides soldiers, sailors, airmen, and bombs to their targets, gives the photographs and signal intercepts to understand what enemies are planning, and provides secure, global communication in an era of global need.

[1] Air Force Basic Doctrine, Air Force Doctrine Document 1, U.S. Air Force Headquarters (Washington, DC: September 1997) 85.

Your monthly East Atlantic edition of Sea Control brings you Alex Clarke with a panel on the state of NATO’s defense spending in the UK and Continental Europe, and whether this spending is sufficient to face our modern threats.

Your monthly East Atlantic edition of Sea Control brings you Alex Clarke with a panel on the state of NATO’s defense spending in the UK and Continental Europe, and whether this spending is sufficient to face our modern threats.