By Chris Peters

When I reached Charlestown Navy Yard on August 19, 2012, it seemed like a perfect morning to be underway in the harbor: clear skies, a forecast high in the mid-70s, and the ship going to sea was USS Constitution, set to sail on her own power for the second time in 131 years. Reporting as her conning officer was certainly the last thing I ever expected to do.

Six months earlier, Commander Matthew Bonner, Constitution’s 72nd commanding officer, asked if I’d be up for the job. Boston NROTC, where I teach navigation and naval operations to midshipmen, has a long standing relationship with Constitution. With only an Executive Officer and Operations Officer, the wardroom would be fully stretched that day. I was understandably more than happy to help out.

Once onboard, I surveyed the area where the navigation team and I would be working. The harbor chart was laid out on a folding table in front of the ship’s proud 10-spoke wooden helm about three quarters of the way aft. Navigation equipment was rather limited; a magnetic compass on each side of the ship’s wheel was the only permanently installed equipment. Technicians from Naval Sea Systems Command, onboard to monitor the stability of the ship, had also installed a digital reader for course and speed.

As the underway time of 1000 neared, the ship was buzzing with activity. Constitution’s normal crew is around just over 50, but they had assistance from 150 Chief Petty Officer-Selects temporarily assigned for a two-week CPO heritage program. Also onboard were several former Constitution commanding officers, Medal of Honor recipient Captain Tom Hudner (Ret.), three flag officers, and the British Consul General. With the crew taking in the last line and casting us into the harbor, I could feel the shared excitement as we began our historic cruise.

There was no conning to be done, initially. One primary tug boat and a backup were towing the ship approximately three miles to a predetermined “sail box” just past the channel entrance where we would have up to a mile to maneuver with sufficient separation from shoal water. Despite not having active control of the ship, two Quartermasters laid regular fixes from a handheld GPS receiver.

Once in the channel, Commander Bonner and the British Consul General laid a wreath overboard to honor the 7 American and 15 British sailors who died in the fierce battle between Constitution and HMS Guerriere 200 years ago that day. Constitution’s vanquishing of the British frigate was a milestone victory for the early U.S. Navy and also the occasion where the ship earned her famous “Old Ironsides” moniker.

Summer weekends are popular times for pleasure boaters in Boston Harbor, and that Sunday was no exception. Hundreds of boats were out in the harbor to catch a glimpse of America’s ship of state, with many trying to follow along for the whole cruise. Fortunately, the Massachusetts State Police, Boston Police, Massachusetts Environmental Police, and U.S. Coast Guard provided escort and protection with a sizable exclusion zone around Constitution.

The two-hour trip to the sail box flew by. Before I knew it, our two tugs were turning us around between Deer Island and Long Island and into position. Around this time our “sail master,” a First Class Boatswains Mate, began barking commands to a hybrid team of Constitution crew and CPO-selects. In well-rehearsed sequence and with dozens of Sailors on various lines, the crew raised Constitution’s three main sails. The world’s oldest commissioned warship was coming to life.

It was almost game time for me and my helmsman, a First Class Sonar Technician. We reviewed what we learned the prior Friday during steering checks: maximum rudder in either direction is 20 degrees, one full turn of the wheel is 10 degrees, therefore each of the wheel’s 10 spokes represents one degree of rudder. There was no rudder angle indicator like one typically finds on ships. Instead, a black marking on the line wrapped around the wheel moves forward and aft relative four rows of line on either side as the wheel turns.

The Quartermaster recommended course 260T to return us to the western end of the sail box and back into the channel. To verify we were on that heading, I called over to the still-connected tug’s captain. Constitution’s two magnetic compasses fluctuated during the transit and now displayed conflicting headings, and since we were still dead in the water, our digital course repeater was unable to help. After verifying that we were on the correct heading, I was ready to go.

“Conn, tug’s cast off!” the Captain yelled to me, and with a “Rudder amidships,” we were off and sailing. The entire crew, who had worked so hard and waited so long for this special moment, erupted in spontaneous applause as the tugs moved away and took ready station off our quarters. I can recall the surreal feeling of looking to my left and right seeing no tugs and knowing that I was playing a small part in navigating this almost sacred warship, and would remember it for the rest of my life.

I allowed myself only a brief period to soak in the moment and then kept my focus on driving the ship. Although we were laying frequent fixes, I relied on input from the Captain, who had climbed partway up the ship’s rigging for a better view. Standing by the helm, one has only a limited view of what is actually ahead of the ship. As we intended to maintain course, only minor rudder adjustments were required.

USS Constitution handled very surely. At roughly two knots speed over ground, we pressed ahead. Our speed, while slow, impressed everyone onboard since we had a tail wind of just about three knots. That was just enough to fill our sails and keep Joshua Humphrey’s brilliantly designed ship moving ahead. News helicopters circled overhead and hundreds of boaters kept up with what must have been a majestic sight. The last time Constitution was underway on sail power was 1997, and prior to that was 1881.

Seventeen minutes later, our brief sail into history came to an end. The tug returned, the crew partly lowered the sails, and Constitution was no longer under our direction. It felt like no time at all, but I relished every second. It was a great feeling to shake hands with the helmsman and quartermasters as we shared congratulations and absorbed up what we had just done.

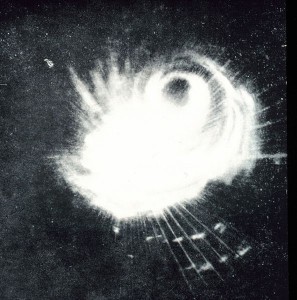

We were not finished yet, though, as the return to Charlestown was still ahead and Constitution still had one more show to put on. The tug brought us to a stop just north of Fort Independence at Castle Island, where thousands (including my mom) had assembled for a view. The crew came to attention, and with a thunderous “boom” a 21-gun salute commenced. Dozens of surrounding boats answered with their whistles and the harbor was alive with enthusiasm. Afterwards, in an unscripted moment, the Chief-selects broke out in “Anchors Aweigh,” soon joined by the whole crew. We sang so loudly that the crowd on shore could hear, I later learned, and they loved it.

Around an hour later, a small crowd welcomed Constitution back to the Navy Yard, and we moored where we had started roughly four hours earlier. Knowing that the day’s events were almost certainly something I would never take part in again, I took time to reflect before disembarking. I thought of naval heroes like Edward Preble and Stephen Decatur who walked Constitution’s decks two centuries before. Considering their bravery, courage, and the impact they and USS Constitution had on our early Navy and the country, I was incredibly humbled to feel so connected to their history. I also thought of the professional, passionate Constitution sailors I met that day. Those impressive men and women are heirs to and representations of our proud past. On August 19, 1812, USS Constitution’s iron-like live oak hull repelled British cannon fire, but it was the courage and resilience of the American Sailor that won the day and continues to keep our Navy strong.

LT Chris Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy and an instructor at Boston University.

The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

Featured Image: BOSTON (Oct. 22, 2021) USS Constitution is underway during Chief Petty Officer Heritage Weeks. (U.S. Navy Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Alec Kramer/Released)