By Matthew Merighi

Join us for the latest episode of Sea Control for a conversation with Professor John Burgess of the Fletcher School about the Law of the Sea and its enduring effects on maritime security. This interview was conducted as part of the roll-out of the Fletcher School’s recently released primer on the Law of the Sea.

Download Sea Control 141 – Law of the Sea with John Burgess

A transcript of the interview between Professor Burgess (JB) and Matthew Merighi (MM) is below.

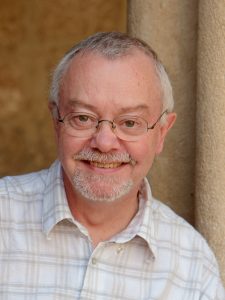

MM: And we’re back as I mentioned at the top I’m here with professor John Burgess of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Professor Burgess thank you very much for being with us on Sea Control today.

JB: It’s my pleasure.

MM: As is Sea Control tradition, please tell us a little bit about yourself. Tell us about what are the main formative experiences you’ve had that brought you from where you were to where you are today.

JB: Well, I’m a Professor of Practice at the Fletcher School and that’s after having worked in law firms for about 35 years. But I did always have an interest in national and maritime security. I took a sabbatical and worked for the U.S. State Department in the area and I’d say the majority of my published articles were in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings, so moving towards maritime security and Law of the Sea as part of the courses I taught here was a pretty natural progression for me.

MM: I guess I’ll probably start the podcast off by mentioning the fact that you have a very robust library of maritime books. I’m curious, you’ve done maritime work but what got you interested in maritime law in the first place? Was it a personal experience or was it kind of discovering it by happenstance through your legal work or what brought you into maritime law?

JB: Well, of course a place like Fletcher been interested in international law and it’s interesting the way fashion works sometimes. The Law of the Sea, as we’ll talk later about the principal Convention, was adopted back in 1994. The course at Fletcher was taught for a while but then dropped out of the curriculum and the more I looked at the issues the more odd that seemed because the Law of the Sea, as embodied in the Law of the Sea Convention, is one of the most comprehensive pieces in international law that exists. And it covers obviously 90 percent of the planet and it raises all the classic issues of international law: how nations work together, how disputes are settled, how resources and rights are allocated, and it crystallizes all of those issues and we face the questions and disputes and developments every day. And so that led me to really want to focus on it in a systematic way. And, of course, here at the school of the international relations, it was a great venue to be able to apply the law to a very rapidly developing set of global situations.

MM: Let’s talk then about the historical underpinnings that have led us to where we are now before we get too far into the current issues. So, the Law of the Sea: tell us a little bit about it. What is it? You talked a little bit about its effects but what is it functionally at its core, why does it exist, what’s the history behind it, and how did it come to be?

JB: To summarize concisely, for the Law of the Sea, one of the reasons that it’s so interesting is that it’s both very old and it’s newest today. When nations began trading, gradually maritime custom and maritime law developed governing those relationships and by the 17th century, international legal thinkers were beginning to think about the ocean as a separate legal space that was not owned by any nation or controlled by any nation, but was a common; shared for commerce and navigation among the world’s nations. And that concept has evolved as part of customary international law for centuries.

After the second World War, in a more complicated world in some ways, with increasing numbers of nation states and technology permitting greater exploitation of oceanic resources, nations began to focus on that system of customary law and whether it should be embodied in a treaty or treaties. And back in 1958, under UN auspices, preliminary group of treaties was adopted, but the scope was limited. And that led to a desire to address, on a comprehensive basis, the issues of Law of the Sea.

Over 10 years, dozens of nations in a conference of Law of the Sea worked to evolve what has become today, the Law of the Sea Convention: a treaty regarding the Law of the Sea, which became effective in 1994. And it is very, very detailed and very broad in its scope. It did several revolutionary things. It defined on a systematic basis a series of maritime zones; parts of the ocean over which states had different rights. And particularly, introduced the concept that we can spend a few more minutes on later, of an Exclusive Economic Zone, the right of coastal states to exploit the living and nonliving resources of the adjacent waters out to 200 nautical miles. It also crystallized in a written form the rights of maritime nations to freely navigate.

That idea that there is an element of the commons that is available for free navigation, the conduct of trade, the conduct of naval operations and at one level, the 1994 treaty of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea is a great compromise that assures developed nations and maritime nations the traditional rights and access of navigation. And developing nations and others have the right to exploit neighboring living and nonliving resources in the sea. Of course, for some countries it’s both; the United States draws great value from its economic zones off its oceans in terms of fishing, mineral, petroleum, other resources and as the world’s leading naval power, it’s critical to the United States to be able to exercise the rights of navigation that are embodied in that treaty.

MM: Before we go into some of those areas and get into the specifics, I was wondering if you could tell us since many of us already know customary international laws but I’m sure there are some people out there that haven’t worked in international relations in the legal space, but walk us through what is customary international law and if that is a form of law, why then would there need to be a treaty and then a Convention to institutionalize that in paper?

JB: Customary international law is sets of practice that are adhered to by the international community as evidenced by state practice, what nations do, as evidenced by the supporting actions of international courts, the adjudication by these commentators, that isn’t written down in a law book, but which by reason of practice over the course of time and the acquiescence of the international community, takes on the nature of law and that is an historic element of international law and is relevant to the Law of the Sea to this day.

The issue with customary international law however is it’s neither comprehensive, things can develop technological enabling or security issues that the law hasn’t addressed before, and you can’t rely on the accumulation of custom to address. And its interpretation is limited in scope but comes up as academic commentators write articles, as courts interpret decisions and with somethings as complicated as the governance of the world seas, something more comprehensive, something that was more up to date in many respects was critical.

I’ll just throw one example and that relates to environmental issues. For protection of the oceanic environment for a variety of reasons, there was no substantial body of customary international law on that topic, and it could’ve taken decades or longer for it to evolve. And by then environmental issues in the 20th century to respect to the world’s oceans could be critical. So, one of the thing that treaty does is systematically set up a regime for addressing those questions. You can’t do that customary international law, you need a treaty.

MM: Let’s start going through the treaty then. You mentioned there’s a number of different areas, but you mentioned first and foremost the fact that the ocean is divided into different zones.

JB: Yes, that is correct.

MM: So, walk us through those zones, what are they, how are they determined, and what can states do in those different zones?

JB: I’m going to walk through it beginning close to land and heading out to sea. And in principal, the rights of a coastal state are highest, this makes sense, closest to land, and are more limited as you go out to sea. Internal waters which are the waters on the landward side of the low tide line are, sovereign territory; those waters are fully subject to the laws of the state, and if you’re on the Connecticut river, you’re under U.S. and Connecticut law as an internal water. But then, on the other side of that baseline, that’s created to determine the outer limit of internal waters, you’re in what’s called the territorial sea, the territorial sea has a breadth of up to 12 miles. States can define it, and most do, out to 12 miles and states, in essence, are sovereign over the territorial waters along their coast as well. They have the full ability to legislate and enforce their laws in those waters. Subject to one very important right that we can talk about later which is a right of innocent passage by third party states to traverse the waters, subject to limitation, but that’s it.

That’s really the only exception or limitation on the coastal states sovereignty. The next key zone is the one I described to you, the one that really was created under the Convention of the Law of the Sea and that is an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). That goes out all the way to 200 miles and it says that the coastal states have the exclusive right in that zone to exploit the living and nonliving resources. The seabed, what’s under the seabed, petroleum, fish, mineral rights, but those otherwise are part of the high seas, they can’t restrict navigation in the way they can in territorial waters, and their rights are therefore limited as opposed to territorial waters.

Once you get beyond 200 miles, it is the high seas, a commons that the world continues to have rights to navigate in. Below the surface, after 200 miles, there may continue to be rights to exploit minerals, under the extended continental shelf. That continental shelf set of rights can extend depending on the geology, it’s a complicated equation of a coastal state, out beyond 200 miles but typically not beyond 350 miles as an outer limit. And beyond that the seabed again becomes part of the common. It’s open to exploitation by all nations, whether they have access to the coast, whether they are landlocked or not, under the separate regime established under the treaty.

MM: So, it’s pretty intuitive then in terms of the rights of different zones and how they’re allocated for large bodies of land, so say for example knowing how far the end of California is from 200 miles, that’s pretty easy.

JB: It is, yeah.

MM: But they’re also notions of a place where there’s a lot of other features, I guess is the technical terminology from there and I think one of my favorites from the Law of the Sea Convention is the difference between islands and rocks. So, I was wondering if you could walk us through the differences between those two features are and how they play into the Law of the Sea?

JB: Yeah, I’m always reminded of the old Simon and Garfunkel song, “I am a rock; I am an island,” but it’s actually a legal concept here, not a musical one, and the key point is that, as you described, if you’re along a continental coastline, it’s pretty intuitive, you get 12 miles and then you get 200 miles. It’s a small percentage relative to the size of the continent, but how do you treat an island? And an island is defined under the Convention as a body of land surrounded by water that’s above sea level at high tide, and it actually creates a territorial sea and an EEZ as well, so if you’re looking at the Florida Keys individual islands that remain above high tide, they have the potential to create, a territorial sea and an EEZ all on their own.

So, I’m going to indulge for a second if it’s okay in a little geometry, let’s say you’re in the middle of the Pacific and you’ve got an island that is a mile wide. Well, it can create a territorial sea and an exclusive economic zone. I’m not great at geometry but I think the area of the circle is πr squared. So, 200 miles and square it: 40,000 miles, multiplied by pi; a one-mile island can create a tens of thousands of square miles of exclusive economic rights. Interestingly enough, that would mean that the nation that has the largest EEZs is the United States because of the range of the islands principally that are United States territory in the Pacific. Surprisingly enough, the next one is France.

MM: France?

JB: To understand that, you need to go look at a map and go “oh yeah French Polynesia or the islands that France controls in the Indian sea, Indian Ocean rather.” And how did they get so big? Because of this leverage and the drafters of the Law of the Sea Convention, they kind of knew that, they said we have to safeguard the abuse of that status so only one kind of island gets those rights. There’s a subset of islands that we’re going to call rocks. And those are islands that can’t sustain human habitation or economic activity. They don’t have to be literally rocks; they could be a sand spit, they could be a coral reef, but if they lack the capacity to support human habitation in a meaningful way or meaningful economic activity, then they do not generate an EEZ. And it eliminates that ability to leverage, so dramatically, the territory of an island to an essence to create very, very significant and valuable oceanic zones. So, they thought of it, but it’s still an issue in today’s law.

MM: So, let’s talk about that a little bit, because obviously the incentive for a country that owns a rock, you know, if it’s not the size of Oahu which has Honolulu on it, but is kind of the cartoon depiction of sort of a person on a tiny deserted island with a palm tree on it.

JB: Yeah with the palm tree on it (laughs).

MM: But the incentive I’m sure for a country with that in order to gain those exclusive economic rights is to say, “oh well, that can sustain human habitation.” So, I was wondering how then is it determined whether a piece of land in the water is an island or a rock? You have this sort of the definitions, but how do you define then human habitation, well, human habitation is pretty easy, but economic activity seems to be kind of fuzzy?

JB: Well, actually both of them are a bit tricky and as typically happens, the treaty doesn’t give you a lengthy piece of guidance on how to do that. And many nations including the United States have, I’ll use the phrase, been liberal in their interpretation whether a feature is an island, for the reasons you described. But in the last year, last summer, an international tribunal on the South Seas, which adds South China Sea in particular, which we’ll talk about, looked at that question and provided some more detailed interpretation and it said a few things.

First of all, when we evaluate whether an island can sustain human habitation or economic life, we’re going to look at the island in its natural state, so for starters, if the Chinese or somebody else build a huge structure or transform the island, you can’t look at that, you have to go back historically, see what it looked like before human intervention transformed it. Secondly, you’re going to look at the ability to sustain human life without massive outside intervention. If you fly in lots of people, you fly in water, fly in food, it’s clear that those external interventions again aren’t the test, you have to look at what is there on the island. And interestingly enough, it doesn’t necessarily have to have a human population. The question is “is there water, are there resources to supply food whether its vegetation or animal or fish that could or does sustain a human population?” And not on a transitory basis, people coming through for two months a year to fish doesn’t count.

Secondly, in the tribunal they also took a hard look at what economic activity or life would mean, and underscored that it couldn’t be merely extractive. You know there are islands that were made of bird dung, guano, and in the 19th century, people would go and mine these islands, well that’s just extractive, that’s not economic life, there has to be some set of resources that would permit economic activity on an island, and that could be mining, it could be fishing, but it can’t simply be mining that cannot sustain and does not sustain a local population. That still raises lots of factual questions in every case, but it does make clear that an island has to be something more than just a palm tree and someone waiting for the ship to come, to qualify. And that’s going to have implications for nations like the U.S. and France and others who have significant island claims.

MM: So, we understand a bit about the zones, how they’re built, how they’re projected out, and some of the controversies surrounding this which we’ll get into the specifics in a bit, but to set up the ground work for everyone out there in our audience, tell us a little bit about what you alluded to earlier, about innocent passage and freedom of navigation. What is it, how does it function, and how does the Law of the Sea Convention define those different kinds of activities? What are the rules of the road?

JB: And those are critical elements because really the Law of the Sea is a balancing of interests of states, the coastal states want to control as much as possible, as far as possible and obviously maritime and commercial states wish to be able to conduct trade and activities without interference by coastal states, and those compromises are reflected in a couple of different concepts.

The first is the concept of innocent passage. As I mentioned a few minutes ago, the sovereign coastal state has a lot of power and authority in the territorial sea, subject to one exception and that is the vessels of third parties can traverse the territorial sea to make a transit or to enter into the ports of the coastal state under the doctrine of innocent passage. The coastal state cannot forbid that kind of transit or activity, and when you think about it that’s pretty critical to commerce, a cargo ship proceeding along the U.S. coast in order to trade in order to access U.S. ports in order to efficiently transit is going to enter territorial waters, and this right of innocent passage allows it to do so, but it’s a very limited right. The passage has to be continuous, it has to be expeditious, you can’t anchor off a coast for a week, absent an emergency set of circumstances, so it’s got that test, and it has a variety of other tests that are designed to assure that innocent passage isn’t exploited to take advantage of the coastal states’ resources or military security.

For example, you can’t fish on innocent passage, because that is in conflict with the rights of the coastal state. You can’t operate military systems, you can’t take on or land aircraft or launch aircraft. Submarines have to proceed on the surface which kind of spoils the whole purpose of being a submarine precisely to avoid provocative threats to the security and safety of the coastal state. So that’s the balance its achieved.

Transit rights relate to a very specific kind of territorial water, and that’s international straits. Straits of water that connect bodies of the high seas or economic zones and you could think of lots of examples: the Straits of Gibraltar, the Straits of Malacca, places which are narrow waterways, that would be the territorial waters of the contiguous states, but this special set of transit rights are granted. It’s rather like innocent passage, but because international straits are so critical to global security and commerce the rules are more relaxed.

I mentioned submarines couldn’t proceed on a submerged basis in innocent passage. They can in transit rights. The number of restrictions on activities in transit rights is much more limited than for innocent passage. And aircraft have transit rights as well as vessels in innocent passage, only surface vessels and submarines have that right. So, this is to the more liberal regime, which is a critical regime to assuring global access to those straits that are fundamental choke points in the conduct of global commerce.

MM: There’s also a concept inside the Law of the Sea called sovereign immunity.

JB: Yes.

MM: I was wondering if you – since that’s at least tangentially connected to innocent passage and freedom of navigation rules – walk us through what is sovereign immunity? What does that mean?

JB: Well, it’s more than in the Law of the Sea; it’s really more of a doctrine of international law that states will not conduct criminal or adversarial actions against other states. And when you think about it, it’s an element of comity and we won’t go on with France interfering with U.S. military aircraft and ships and France similarly does not want us doing the same with theirs. But its significant with the Law of the Sea in that many of the provisions in the Law of the Sea exempt vessels that are subject to sovereign immunity or aircraft that are subject to sovereign immunity. For instance, the anti-pollution provisions don’t apply to a U.S. warship or a French warship for that matter.

In innocent passage, it’s an interesting dynamic because it basically says that if a ship that has a right to sovereign immunity violates the ground rules for innocent passage, the coastal state has the right to take steps to ask it to cease the passage. What that means isn’t entirely clear, it is in fact very likely that there’s no right of force or coercive ability to force the sovereign immune vessel to change its course and conduct, so implicit of that is risk of standoff and certainly the rights against the sovereign immune vessels are more limited. And state interference with those kind of vessels is a very serious breach, not just of Law of the Sea but of international law, which was why when the Chinese picked up a drone operated by the U.S. vessel, which is subject to sovereign immunity, it was a U.S. government vessel although not a naval ship as such, that raises implications of a breach of sovereign immunity.

MM: So then let’s talk about some of the specific examples since you mentioned China, since that’s the one that probably most of the people out here are familiar with. Walk us through the South China Sea, why is the Law of the Sea a part of the disputes happening there? What does it say about the disputes that have been happening and how is it generally guided the developments that have happened in that region?

JB: Well, in some ways it’s a textbook example of the importance of the Law of the Sea because the South China Sea is fraught with conflict. There are small islands: the Spratlys, for instance, and the Paracels that are claimed by the multiple adjoining states. The claims with respect to economic zones and extended continental shelf create issues of overlap and conflict. And, this is in a region where suspicion and friction between the neighboring states is high, so the ground rules of the Law of the Sea are critically important element in helping to resolve the frictions that are embedded in the issues I just described to you. And one of the key elements has been the tension between the Chinese view of its rights with respect to the South China Sea and those of the adjoining states.

The international tribunal decision at the permanent court of arbitration in 2016 that I mentioned earlier, really arose out of that and some other related disputes, but the principal core was with respect to China’s view of its rights over the South China Sea. China has asserted that it has broad sovereign rights within an area defined by the so-called 9-dash line, and that expression comes from the fact that the map that originally included it had nine dashes, the number of dashes varies from time to time, that doesn’t matter. What does matter is that the line embraces the great majority of the South China Sea. It comes down close to Indonesia, Vietnam and to the Philippines. And the line conflicts with the Exclusive Economic Zones of those nations. China’s never defined precisely, and certainly not in the context of the Law of the Sea, what it means by the sovereign rights under the 9-dash line, but both verbally and in action, has asserted rights that would be in conflict with the Law of the Sea for instance, the access of Filipino fishers to living resources within the South China Sea has been restricted by the Chinese on the basis of the 9-dash line.The tendency of China to increasingly enforce or assert the 9-dash line was triggered when Vietnam and the Philippines began oil exploration in the South China Sea.

The tribunal took a hard look at the 9-dash line, and it unequivocally said that, this line which China asserts has its origins in ancient historic rights to the sea is in conflict with the Convention of the Law of the Sea and hence is legally of no effect. The tribunal said that when China signed the Convention, it gained great rights including to the EEZ around China that didn’t exist before, and in doing so, also lost any more vague and historic claims. And that was a very important decision both legally and geopolitically. It’s no question that legally it was the right decision. This kind of broad, inchoate historic right to great reaches of water doesn’t exist anywhere in the Law of the Sea. And in addition, it was a firm message that, from a political standpoint, China’s position was an overreaching assertion of sovereign rights, which is one of the reasons why the Chinese have so bitterly denounced the decision.

MM: So, let’s talk about the other end of this, since we’ve talked mostly about the economic rights, let’s talk about freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, because you mentioned the drone seizure, what then does the Law of the Sea say should be happening in the South China Sea and what is the position of China, how they’re acting, and how do they contrast with one another?

JB: Yes, the tribunal did not address that set of issues, but it has been an escalating and critical source of friction as well particularly although not exclusively between the U.S. and China. And it has two elements, the first relates to innocent passage. I’ve described that before, it’s the right for the continuous and expeditious crossing of territorial seas, innocent passage is available to warships as well as civilian vessels, but a certain number of nations including China have asserted that it’s necessary to provide notification and to obtain consent to conduct innocent passage. The U.S. position, which is consistent with the Convention, is that that consent is not required.

That war honestly has been more one of words than of action perhaps fortunately. The U.S. conducts what it calls freedom of navigation exercises from time to time to preserve those rights. It’s complicated in the South China Sea because those navigation exercises have sometimes been ambiguous, the U.S. has sailed within 12 miles of certain of these small maritime features and it’s been unclear whether the U.S. is in fact asserting innocent passage and conceding there’s a territorial sea around the feature, or is the U.S. asserting that there’s no territorial sea, and is simply a high seas transit right, and that ambiguity continues. China protests those exercises, we periodically conduct them, as I said the struggle has largely been one of words, but it is important and as a security matter for the United States, the assertion of the right of innocent passage within the South China Sea is very important.

The other and more broad question is, whether there are any limitations on the conduct of military surveillance, reconnaissance, or activities within China’s EEZ. And China also interprets its rights there very broadly. It asserts that the EEZ can only be used for peaceful purposes and that reconnaissance flights, this is beyond the 12 miles remember, it’s out beyond that zone, or military exercises are inconsistent with its interpretation of the Convention. And that has led to serious difficulties.

More than a decade now ago, there was a collision between a Chinese interceptor aircraft and a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft, the Chinese pilot was killed and his plane crashed, the U.S. aircraft was forced to land on an emergency basis on a Chinese airbase. And unfortunately, with the last couple of years, nothing that serious has occurred, but there have been recurring games, for the lack of a better word, of international chicken between Chinese interceptor aircraft and U.S. reconnaissance aircraft. And the risk of an incident there is real. And again, arises from the U.S. goal of assuring, particularly as a major power in the region and as a leading naval power, that its high seas rights are preserved. The erosion of that would be a serious blow to U.S. security interests, and China’s assertions that at least within the EEZ, conduct of that nature is not allowed of absent Chinese consent.

MM: So, lest our audience assume that basically every tension over the Law of the Sea somehow involves the United States and China or let’s be honest, sometimes just China and its neighbors, tell us a little bit about the United States and Canada and its disagreements on freedom of navigation.

JB: What could be friendlier than the United States and Canada? But things do happen when the issues are ones critical to open navigation to the principles of Law of the Sea and to access resources and that’s shown up between the United States and Canada on an abiding disagreement regarding the fabled Northwest Passage, the sea route through the Canadian island chain, that once upon a time explorers hoped led directly to El Dorado, but now with melting arctic ice may offer a way through the great circle route to significantly reduced transit time between the U.S. east coast and Asia.

The Canadian position is that they are internal waters and if you recall, internal waters are equivalent to sovereign territory, there are no rights of third party nations and the rights abide exclusively with the coastal state. And in some ways, this has become a key psychological element to the Canadians, the Northwest Passage being truly part of the “Canadian north” or the “Canadian arcti”c, however you define it. The U.S. perspective is rather different. It is that the Northwest Passage is in fact an international strait, a way to connect two sets of high seas, and is subject to the transit rights available to third party nations under international law. And that therefore for example, a U.S. ship could proceed through the northwest passage without consent or notification, provided that it abided by the rules applicable to transit passage.

This disagreement remains more theoretical than real in the sense that traffic obviously through the Northwest Passage is limited. The two states have agreed to share information regarding such passages without the United States in anyway acknowledging that Canadian waters are internal and without Canada acknowledging in any fashion that the Northwest Passage is an international strait. And part of the disagreement turns on what an international strait mean. What does it mean to be used to permit passage between two sets of high seas or EEZs? Does “real use” constitute part of that definition? Because historically transit to the Northwest Passage relative to most other international straits has been very limited.

The U.S. view is that it can be used and it has been used whether or not it’s a large number of times and hence it’s a strait. The Canadian view is that that’s not the case because usage has been highly limited and doesn’t correspond to what has been historically associated with international straits. There are ironies to the position on both sides, I will note that it’s not entirely clear that it would be a geopolitical victory for the U.S. if it is an international strait, because for example, that means that Russian reconnaissance aircraft are free to fly down the straits under rights of transit. On the other hand, from the U..S standpoint, the principle at stake is critical because if there is any evolving body of law that erodes the definition of international straits, it’s a clear detriment to a leading maritime and a naval nation like the United States, so it does matter.

MM: So, the Canada issue and the strait versus internal water alludes to the fact that the ocean is changing and that as a result of the changes in the ocean, it is also then driving changes in the Law of the Sea, if not the law itself, but in terms of evolving issues that are coming up. So, besides the Canada strait versus internal waters issue, what other issues do you see coming down the pike for the Law of the Sea?

JB: Well, the issue you just alluded to is one of them. And as you also mentioned it goes well beyond the question of the northwest passage. As we’ve talked about before, the definition of the low tide line is a very important marker, one of the key ways, not the only way, but one of the key ways that the baselines from which the maritime zones are measured is defined. We had a discussion about the difference between a rock and an island.

Well imagine if as it seems to be the case, global sea levels are rising, there are currently islands that are a meter or two above sea level. Given another 50 or a 100 years, if current trends continue, that could fundamental impact on the definition of maritime zones. They may be retreating landward. There are islands which would disappear, eliminating EEZs, or territorial seas associated with those islands. And there’s no resolution today about whether the baseline should be frozen and the way the borders are defined today is embedded, at least for some period of time, or whether they’re ambulator: the legal word for walking around, whether they reflect adjustments in sea level.

There are groups under the International Bar Association and U.N. auspices looking at it and it’s a real question. Let alone dealing with the broader question which is not purely a Law of the Sea question of what becomes of island states, small nations in the Pacific or the Indian Ocean, it’s not simply a question of maritime borders disappearing, but of a country disappearing. And what is the status of a country’s sovereignty and what happens to its population? So it’s a good thing that it isn’t going to happen in the next five years, because it’s going to take a lot longer to resolve issues of that depth and complexity.

MM: So, as is Sea Control tradition since we’re approaching the end, please walk us through what it is that you’re reading right now. You obviously have a very interesting and diverse background in terms of you know your education. So, tell us a bit about what you’ve been reading lately, whether its Law of the Sea-related or maritime-related, even if it’s something fun you found online recently.

JB: Yeah, well I think I describe two things. One is kind of a pure Law of the Sea book, but it covers a bit different topics then we’ve been discussing but one that the audience might be interested in is and that is a book by Natalie Klein on maritime security and the Law of the Sea that talks about issues we really couldn’t talk about today, including piracy and weapons of mass destruction and issues of intersection of security issues and Law of the Sea. And I’ve also been reading a book on the Barbary pirates which is a kind of a classic set of questions that relates to the history of U.S. frigates but also these, some of these issues were present at the beginning of the United States, issues of control of piracy, freedom of navigation. If the Barbary pirates were anything, they were dedicated to limiting freedom of navigation and exploiting the sea in a way that was at odds with freedom of commerce and of security.

MM: Wonderful, well thank you very much again professor for being with us on Sea Control and best of luck with all of your work. And hopefully we’ll be able to welcome you back on again at some point in the future

JB: My pleasure, thanks a lot.

John A. Burgess is Professor of Practice and Executive Director of the LLM Program at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. He teaches courses on international finance transactions, international securities regulation and cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

Matthew Merighi is the Senior Producer of Sea Control and Assistant Director of Fletcher’s Maritime Studies Program.

Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.

Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.