By Dmitry Filipoff

From July 20 to August 3, 2020, CIMSEC featured a wide array of publications on the future of ocean governance, submitted in response to our call for articles issued in partnership with the Stable Seas program of One Earth Future. This turned out to be one of the most viewed CIMSEC topic weeks, and which featured insights from a wide range of authors.

Ocean governance is in a state of flux. Legal regimes are being revised, and maritime powers are employing hybrid tactics that seek to exploit the seams of legal frameworks and norms that constitute ocean governance. Non-state actors such as pirates, smugglers, and others are constantly innovating to further nefarious activity. The rules and standards that underpin good order on the high seas must keep pace with those who are keen to exploit them.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing is emerging as a significant issue. These natural resources require careful tending if they are to be sustainable, but aggressive fishing fleets, especially China’s, are depleting a resource that has long provided for millions. If revised regimes and norms cannot restore the world’s fisheries, they may become a major driver of competition and conflict in regions already suffering from tension. As the Cod Wars between allied Iceland and the United Kingdom revealed, fisheries can be, in the eyes of some, worthy of threatening broader conflict.

Ocean governance is explicitly tied toward the ability to effectively monitor and respond to crimes. But the vast expanse of the world’s oceans allows many criminals and nefarious actors to operate openly and in plain sight, unless someone has the means to both watch and react. Ocean governance is inseparable from maritime domain awareness, and developing greater awareness is often the first step toward establishing responses and distributing resources. Those who are tasked with enforcing good order on the seas will almost always suffer a dearth of monitoring and response capability, but ingenuity in the application of both will reap rewards.

Ocean governance is more than just combatting pirates or smugglers, illegal fishers or non-state actors. Ocean governance encompasses efforts that seek to prevent North Korean container ships and their partners in violating sanctions, or in understanding which hybrid warfare methods are more a legal matter than a military one. Ocean governance is center-stage in matters of great power competition, whether it be China’s nine-dash line in the South China Sea, or Russia’s maritime activities around the Crimean peninsula.

What is clear is that ocean governance deserves greater attention from policymakers, and the foresight to recognize that if many issues are not settled through enhanced ocean governance today, then later they may become far more expansive problems in the future.

Below are the articles that featured during the extended topic week, with excerpts. We thank these authors for their excellent contributions.

“Unauthorized Flags: A Threat to the Global Maritime Regime,” by Cameron Trainer and Paulina Izewicz

Fraudulent and false flagging is a complex issue requiring action from multilateral organizations like the IMO, national authorities, and the private sector. Each of these actors has a different set of incentives. Much is at stake for the private sector…The temptation to pass responsibility for combatting unauthorized flag use to others is immense. But it is only through steps taken collectively by all relevant stakeholders that this problem can be addressed.

“Stand Up A Joint Interagency Task Force To Fight Illegal Fishing,” by Claude Berube

Between NGOs, elements of U.S. government agencies, and Congressional legislation, there are positive moves toward addressing IUU fishing. Given the rapid depletion rates of fish stock, China’s growing global presence, and the impact of IUU fishing on economies, more action must be taken. Part of that action requires a reassessment of real innovative and adaptive measures that NGOs have used in partnership with host nations to counter what may be the greatest challenge in the twenty-first century.

“Reflecting the Law of the Sea: In Defense of the Bay of Bengal’s Grey Area,” by Cornell Overfield

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), more than any other implement of international law, has underpinned the orderly delimitation and governance of the world’s oceans. Despite its status as an unparalleled accomplishment of diplomacy and international law, the treaty is not exhaustive or without ambiguities. One outstanding issue in delimitation arbitration is the relationship between the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf – specifically whether one state’s EEZ rights can overlap with another state’s continental shelf rights. What deserves greater attention is how recent court maritime boundary delimitations derided by some observers as legislation from the bench in fact follow the black letter of the law more closely than state practice or previous court decisions.

“Make Maritime Stability Operations a Core U.S. Coast Guard Mission Focus,” by Dan Owen

Fortunately for the U.S. and the larger international development community, a basic framework or mechanism to address maritime instability already exists, called Maritime Stability Operations (MSO). Additionally, one U.S. government agency in particular is especially qualified and well-suited for this mission, the U.S. Coast Guard.

“Stop Seabed Mining Now,” by Drake Long

Seabed governance is going to be one of the thornier issues for a humankind more dependent on the oceans and coasts in the future, and the foundation needs to be laid now for an approach that does not imperil the seabed’s ecosystem for a very dubious profit. National governments may be too indecisive to come to consensus, and international organizations like the ISA are ill-equipped to enforce anything even if they do have a change of heart or code. The process of better seabed governance begins with increased scrutiny, and will largely depend upon an alliance of marine environmentalist non-governmental organizations and the scientific research community.

“Regional Maritime Security Governance and the Challenges of State Cooperation on Piracy,” by Dr. Anja Menzel

Threats to maritime security cannot be understood in isolation, as they are deeply interrelated. Going forward, maritime security governance will therefore need a more integrated understanding of the hazards posed by maritime crimes as well as the potential of coordinated efforts to combat these crimes. Specifically, it is necessary to strengthen maritime domain awareness by emphasizing potential synergies between combatting maritime crimes with the blue economy and the safety of the marine environment.

“Fight Illegal Fishing for Great Power Advantage,” by Matthew Ader

IUU fishing is an ongoing humanitarian, economic, and environmental disaster. Working to stop it will be relatively affordable and advantageous for the U.S. if it leverages regional partnerships and interagency assets. More work should be done to explore the possibilities it offers as a matter of urgency.

“The Cod Wars and Today: Lessons from an Almost War,” by Walker Mills

Not once, but three times in the 20th Century, cod was almost the causus belli between Iceland and the United Kingdom in a string of events referred to collectively as the “Cod Wars.”1 The Cod Wars, taken together, make clear that issues of maritime governance and access to maritime resources can spark inter-state conflict even among allied nations. Fishing rights can be core issues that maritime states will vigorously defend.

“Arctic Governance: Keeping the Arctic Council on Target,” by Ian Birdwell

This June has been unsettling for the Arctic. Russia experienced three events the Arctic Council has been dreading for years: an oil spill, an outbreak of wildfires, and the hottest Arctic temperature record being set with a 100-degree Fahrenheit day in Siberia. However, Russia is not alone in addressing these events. The Arctic Council, the Arctic’s premier multilateral organization, has sought to prepare the region and the globe for the eventuality of a warmer Arctic.

“Maritime Crime During the Pandemic: Unmasking Trends in The Caribbean,” by Dr. Ian Ralby, Lt. Col. Michael Jones, and Capt. (N) Errington Shurland (ret.)

To keep pace with and ultimately get ahead of the criminals, CARICOM member states will need to explore a range of tools for addressing the full spectrum of illicit maritime activities. This includes using new technology such as maritime domain awareness platforms, enhancing operational cooperation through CARICOM IMPACS and the RSS, and both adopting and implementing legal instruments such as the Treaty of San José. While the pandemic has curtailed and thwarted many good things around the world, it somewhat ironically has helped catalyze this process in the Caribbean.

“Ocean Governance and Maritime Security in The Gulf of Guinea,” by Bem Ibrahim Garba

Much can be achieved through the collective efforts of these coastal communities when they come together as progressive stakeholders for the governance of the Gulf of Guinea. Effective ocean governance within the Gulf of Guinea will require their collective identification of common goals and the implementation of collectively agreed upon effective strategies for managing the region. These must all be built on enduring institutional structures.

“Using Geospatial Data to Improve Maritime Domain Awareness in the Sulu and Celebes Seas,” by Michael van Ginkel

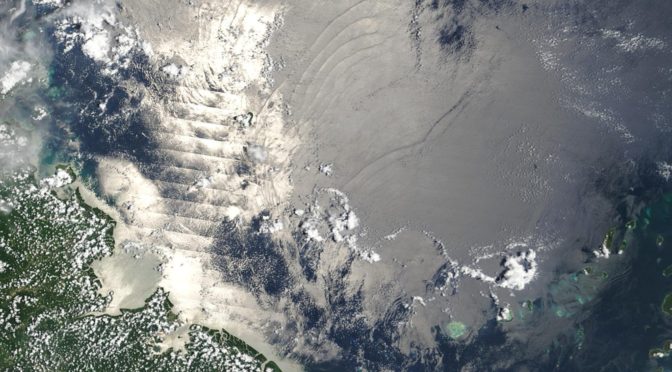

Sprawling archipelagos and limited government resources make comprehensive maritime domain awareness (MDA) challenging in the Sulu and Celebes Seas. To improve their information gathering capabilities, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines have invested in advanced geospatial data acquisition technologies like unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and satellites.

“In the Deep End: How Seafarers Are Redirecting Security Consciousness,” by Jessica K. Simonds

Seafarers engage in various security practices while transiting the Straits of Hormuz, Bab Al-Mandeb, the Gulf of Aden, and the broader Indian Ocean. How have these practices developed to identify and communicate emerging maritime threats based on how seafarer feedback has been incorporated within strategies that counter piracy?

“Implications of Hybrid Warfare for the Order of the Oceans,” by Alexander Lott

Since Frank Hoffman coined the term “hybrid warfare” in 2007, numerous articles and books have been written on this theme from the perspective of military studies and international relations. Yet the existing legal literature has not so far focused on the challenges that hybrid warfare poses for the order of the oceans. One of the main current research gaps lies in the lack of clear understanding on how the law of the sea operates in hybrid warfare.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Content@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: An overhead view of a container ship (Getty)