Navy Warfare Development Command’s Junior Leader Innovation Symposium was a great success. Thanks to LT Rob McFall and LCDR BJ Armstrong for their presentations – they were truly a highlight of the day and both presenters graciously plugged the NextWar blog. Also, the Naval Institute’s Sam LaGrone was on hand to talk about USNI’s new “News and Analysis” platform. This is a daily must-read, especially today’s piece by Dr. John Nagl on the submarine force. As a proud USNI member since 1997, I find the speed at which USNI is adapting to the new media landscape is truly impressive. Finally, the staff at NWDC is consistently welcoming and encouraging to junior naval professionals. Rear Admiral Kraft even took time out of a busy day to chat with this humble blogger. If you have an idea to make the navy a more combat-effective organization, NWDC is the most fertile place I’ve seen to grow that idea into something tangible. Get in touch with them!

But the title says this is about gladiators versus ninjas, you say. Where’s Russell Crowe? Allow me to digress…

Another of yesterday’s speakers gave me some food for thought – the Office of Naval Research’s Dr. Chris Fall. During his talk, he discussed using social platforms to vote for innovative concepts. Similar to the “like” function on facebook, these web applications promote innovative proposals based on the votes of other users. Dr. Fall specifically cited the Transportation Security Administration’s IdeaFactory as an example of this type of system. One aspect of the platform Dr. Fall mentioned raises several questions about innovation: all IdeaFactory proposals must be submitted publicly, using the employee’s real name.

Another of yesterday’s speakers gave me some food for thought – the Office of Naval Research’s Dr. Chris Fall. During his talk, he discussed using social platforms to vote for innovative concepts. Similar to the “like” function on facebook, these web applications promote innovative proposals based on the votes of other users. Dr. Fall specifically cited the Transportation Security Administration’s IdeaFactory as an example of this type of system. One aspect of the platform Dr. Fall mentioned raises several questions about innovation: all IdeaFactory proposals must be submitted publicly, using the employee’s real name.

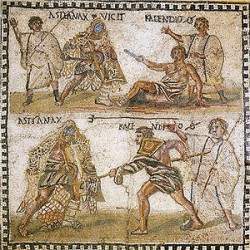

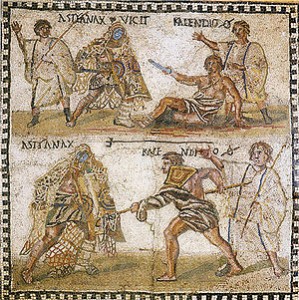

To what extent does innovation have to occur in public? Does anonymity promote or inhibit innovation? What is the career consequence for those who make more radical proposals in this system? As these questions came to my mind, I likened the public option to being a gladiator: your work is intensely scrutinized in full view of an audience. Anonymous writers are like the ninjas of feudal Japan, striking from the shadows.

We always seem to start discussions of professional writing and innovation with a discussion of career risk. As a writer working in both web and print, I want to throw out the disclaimer that the decision to speak, write, or blog publicly or anonymously is deeply personal and depends on circumstance. I don’t begrudge anyone who writes under a pseudonym, which has a venerable lineage extending far before “Publius” and The Federalist Papers. That being said, I think that writing publicly carries some advantages:

We always seem to start discussions of professional writing and innovation with a discussion of career risk. As a writer working in both web and print, I want to throw out the disclaimer that the decision to speak, write, or blog publicly or anonymously is deeply personal and depends on circumstance. I don’t begrudge anyone who writes under a pseudonym, which has a venerable lineage extending far before “Publius” and The Federalist Papers. That being said, I think that writing publicly carries some advantages:

- Attaching one’s name and reputation to a piece of writing creates a drive for excellence difficult to replicate when writing anonymously. None of us wants to be criticized, so public writers have more incentive to hone their arguments; ultimately, the better arguments will stand the best chance of adoption and implementation.

- Writing anonymously allows people to speak truth to power, but it also diminishes responsibility. As a result, anonymous writings can often devolve into mere complaint and invective. Public writing, while less able to challenge authority, also produces more measured, balanced prose and often proposes solutions instead of merely lamenting a problem.

- Being creatures of ego, we want credit for a winning concept. Public writing best enables that credit to be given fairly in the marketplace of ideas.

In other words, public writing may be a means to mitigate career risk rather than the source of that risk. There is certainly a time and place for writing anonymously, but if you have something to say about the Navy, consider your subject and your objectives. The smart move might involve attaching your real name to a point paper or blog post. We romanticize both the gladiator and the ninja in art and cinema. But each only makes sense when rooted in their particular historical and social circumstance. So it is with professional writing. If you have an innovative idea, the smart bet might indeed be to step into the gladitorial ring.

In other words, public writing may be a means to mitigate career risk rather than the source of that risk. There is certainly a time and place for writing anonymously, but if you have something to say about the Navy, consider your subject and your objectives. The smart move might involve attaching your real name to a point paper or blog post. We romanticize both the gladiator and the ninja in art and cinema. But each only makes sense when rooted in their particular historical and social circumstance. So it is with professional writing. If you have an innovative idea, the smart bet might indeed be to step into the gladitorial ring.

LT Kurt Albaugh is a Surface Warfare Officer and Instructor in the Naval Academy’s English Department. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.