By Dmitry Filipoff

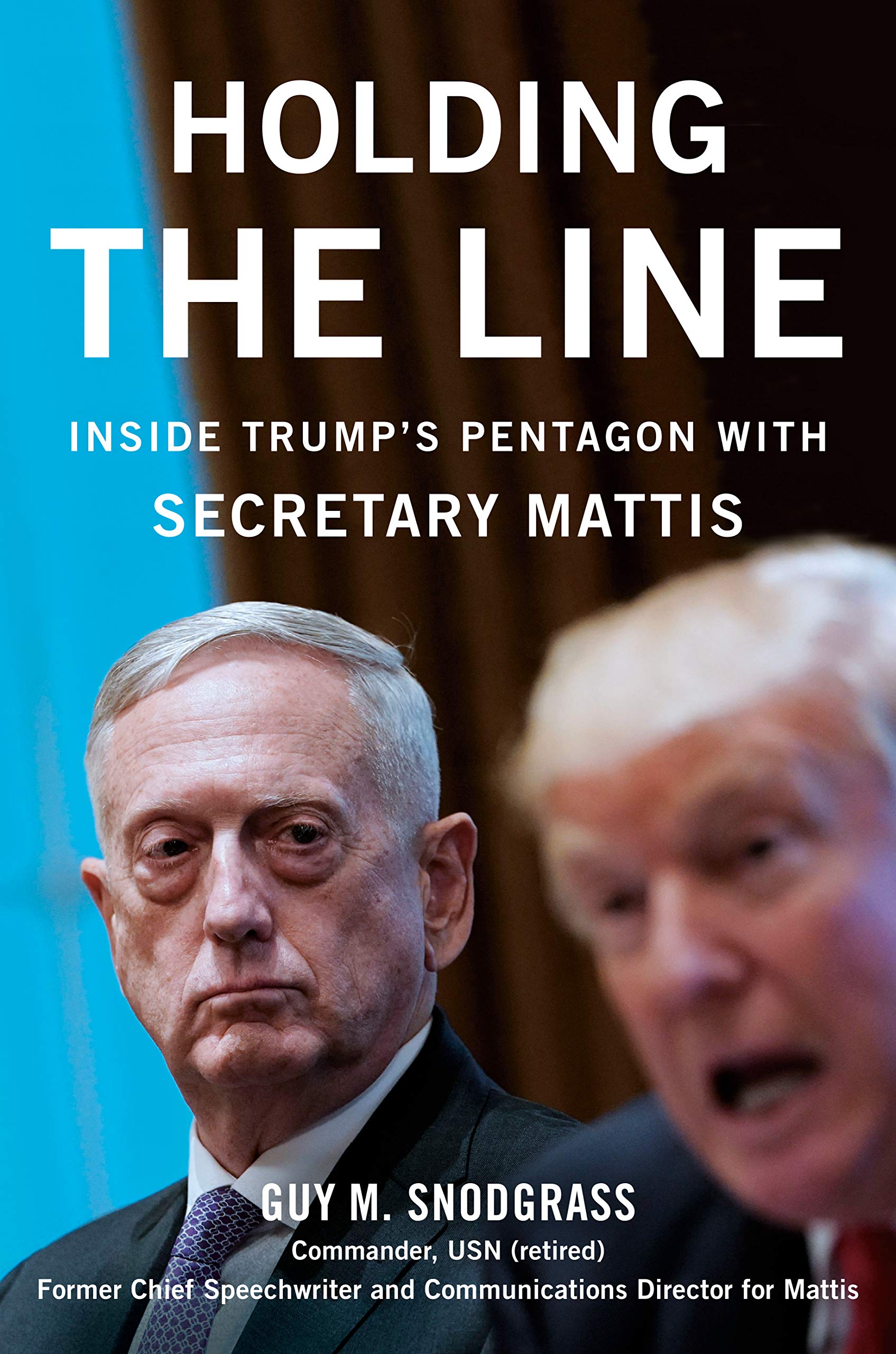

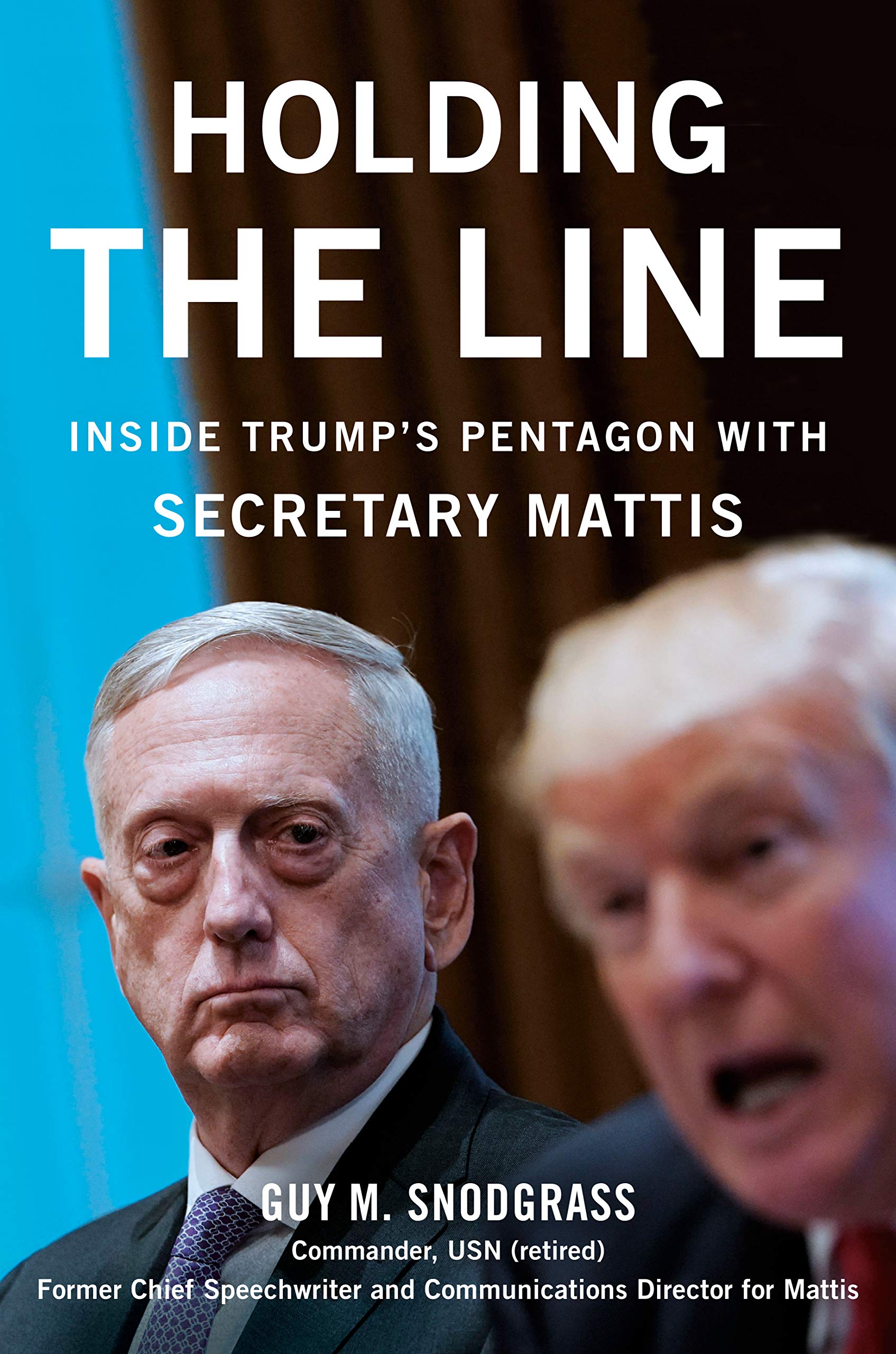

CIMSEC had the opportunity to discuss with Commander Guy “Bus” Snodgrass, USN (ret.) his new book, Holding the Line: Inside Trump’s Pentagon with Secretary Mattis.

The book takes readers inside the trials and successes of Defense Secretary James Mattis as he sought to transition the Defense Department toward great power competition, while also managing international tensions and uncoordinated White House policy shifts. Snodgrass reveals how civil-military relations fared under the Trump administration, how Mattis worked behind the scenes to reassure allies in spite of the president’s rhetoric, and how Mattis offered steady leadership in turbulent times.

What made you want to write this book?

GS: A former Navy officer, I was taught early in my career the importance of passing on thoughtful lessons to those who will follow in our footsteps.

So, I thought it was important to write this book. Consistent with the oath I took, I saw it as providing a service to the American people and those who would follow in my footsteps. I want readers to be able to share in my personal experience.

I was an eyewitness to an important, but under-documented, moment in American history, especially as it related to America’s military. I feel it’s also important to underscore the role our military plays in today’s hyper-politicized national security environment.

There’s a difference between talking out of school while on your boss’s staff or while they’re still in office. It’s quite another to reflect on the experience once they’re out of office in order to share lessons that others may benefit from.

Secretary Mattis is noteworthy for being a recently retired general who served in the top civilian position at the Defense Department. This came at a time when the White House delegated more operational authorities to DoD, and a growing perception that DoD civilians have waning influence compared to their military counterparts. How would you characterize civil-military relations under Secretary Mattis?

GS: There are several passages and chapters in the book dedicated to exploring this theme.

Frankly, it was a challenging time for civ-mil relations. Far more junior (and active duty) military officers were expected to routinely provide direction to far more senior (and presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed) civilians. This was a construct fostered (and demanded) by retired Admiral Kevin Sweeney, Mattis’s chief of staff, and then-Rear Admiral Craig Faller, Mattis’s senior military assistant. We all worked within these confines to the best of our ability, but the minimization of civilian leaders, especially during Mattis’s first year, was a regular topic of conversation around the Pentagon.

As with any leader, as subordinates you are expected to align with their vision and requirements to achieve mission success. In some cases, Mattis’s decision to lead in this fashion resulted in wins (the ability to move fast on issues of national and international significance), but it also reduced cohesiveness, diminished morale, and reduced the initiative of those in the lower ranks of the various OSD components.

When the president unexpectedly announced policy by tweet, whether Syria withdrawals or banning transgender people from serving, it clearly went against a core tenet of Mattis’s that was repeated throughout the book, the importance of alignment and coordination. When the president announced national security policy shifts with no warning or consultation, how did the damage manifest, and how would Mattis manage the aftermath?

GS: You are referring to Mattis’s template of working to ensure “transparency and alignment” within the Pentagon. To your point, we were caught off guard by numerous announcements, most notably the transgender ban, the creation of a Space Force, the cessation of military exercises with our South Korean allies, and the July 2018 threat in Brussels to withdraw the U.S. from NATO.

This is akin to drawing your pistol from its holster, then blowing a hole in your own foot.

There’s also no strategy behind these impulsive announcements. It’s not that they are staged for effect. When the president tweets a new policy shift, it tends to catch the administration off guard and, in many cases, our international allies and partners off guard as well.

The obvious danger is threefold: first, the administration is unable to coordinate, diminishing the ability to provide the president with a well-coordinated response that would better serve his policy decisions; second, allies and partners question America’s new course and wonder if America still remains the leader of choice in regions around the world; and third, our adversaries and competitors—nations like China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea—are emboldened, and seek to exploit America’s perceived weakness/retrenchment.

For his part, Mattis would field phone calls from leaders around the world seeking reassurance. He would continually assure them that “America first does not mean America alone,” and that we still understood the importance of our alliances and commitments around the globe.

The book shows there was plenty of daylight between Mattis and President Trump when it came to managing relationships with allies. How did Mattis walk the tightrope of aligning with the president while also staying true to his own longstanding views of how to work with allies and respect their contributions despite policy differences?

GS: Mattis continually reinforced that “there should not be one inch of daylight” between the public pronouncements from the White House and the Pentagon.

That being said, Mattis worked behind the scenes to provide his best advice to President Trump and others in the administration. He also worked closely with international leaders, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in particular, to reassure allies of America’s continued commitment to longstanding coalitions and alliances.

Secretary Mattis was considered one of the “adults in the room” who could manage Trump’s negative tendencies while also defending established policy. But as you note, after the ousters of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, National Security Adviser Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, and Chief Economic Adviser Gary Cohn, Mattis was essentially the last man standing. How did Mattis’s ability to deal with the White House change after these senior officials were pushed out?

GS: I dedicate an entire chapter of the book, “The New Team,” to this change in Mattis’s stature within the administration. In short, it was readily apparent that Mattis was in trouble by April 2018. National security adviser H.R. McMaster and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson both departed in relatively short order, leaving Mattis to wade into the role of running interference when disagreements in policy arose from within the White House.

In addition, the arrival of Mike Pompeo and John Bolton into their respective roles—both skilled political operatives— continued to diminish Mattis’s influence with President Trump.

I highly recommend the book, as it provides a firsthand portrayal of how Mattis navigated his role throughout his two years within the administration.

Secretary Mattis found himself taking on a role as a senior diplomat, arguably more so than is usual for a Defense Secretary, and perhaps even a more trusted and credible diplomat than the first Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson. This occurred as the administration was attempting major cuts to the State Department and slashing the ranks of career diplomats. How did Mattis advocate for diplomacy as a tool of national security, and how was his interagency relationship with the State Department in particular?

GS: Mattis made clear that he and Tillerson were joined at the hip on the importance of diplomacy. Mattis continually deferred to Tillerson on issues of diplomacy, making sure that we all understood that the DoD’s role was to ensure America’s diplomats spoke from a position of strength.

From my perspective, Mattis and Tillerson shared very similar worldviews regarding the importance of American participation in the international community, and on the importance of strengthening—not diminishing—our longstanding alliances and partnerships. As Churchill said, “The only thing more difficult than fighting alongside your allies, is fighting without them.”

The internal divisions within the State Department, Tillerson’s relative disconnect from his own rank and file, and the media’s relentless coverage of Tillerson’s problems at State rapidly diminished his standing with the president, reducing his ability to advocate for State’s position within the White House.

In your roles as speechwriter and communications director you became intimately familiar with Mattis’s voice and views. What was that like, and how did it shape your view of Mattis?

GS: In several chapters of the book, I bring the reader into this process: the resources we had available to better understand Mattis’s worldview, our interactions with him on a continuing basis, and how we navigated crafting speeches that would require minimal interaction on his end. At the end of the day, the best possible outcome was a speech that I would send in to Mattis, and he would pass it back with no changes, or with minimal corrections.

The role of chief speechwriter really afforded the incomparable opportunity to study Mattis up close and personal, to understand his worldview, and to be able to “channel” his words on the national and international stage.

It was an honor to have the opportunity to serve in that capacity, and to work alongside many stellar civil servants and military members throughout the Pentagon, as well as alongside two very talented speechwriters.

Any final thoughts to share?

GS: Only that a lot of thought and consideration went into crafting this book, to include reaching out to senior mentors for their advice early in the writing process. It was important to craft a book that was historically accurate, that presented an apolitical view of Mattis’s two years in office, and that would stand the test of time. I saw it as a continuation of my service to capture my firsthand experiences in a memoir, one where I could also share lessons learned for those that read the book, and for those that will invariably follow in our footsteps.

Guy “Bus” Snodgrass recently served as director of communications and chief speechwriter to Secretary of Defense James Mattis. A former naval aviator and F/A-18 pilot, he served as a commanding officer of a fighter squadron based in Japan, a TOPGUN instructor, and a combat pilot over the skies of Iraq as part of his twenty-year navy career. Today he is the founder and CEO of Defense Analytics, a strategic consulting and advisory firm.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at [email protected].

Featured Image: Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis briefs the press at the NATO Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, June 29, 2017. (DOD photo by U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Jette Carr)