By Matthew Merighi

Join us for the latest episode of Sea Control for an interview with Admiral Charles Michel, the Vice Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, for a discussion about his service’s unique role in ensuring international maritime security. From his vantage point at the intersection of military force and law enforcement agency, he discusses some of the emerging threats in the maritime domain, how cyber challenges affect the Coast Guard’s mission, and the enduring importance of protecting global supply chains.

Download Sea Control 140 – The Coast Guard with Admiral Charles Michel

A transcript of the interview between Admiral Michel (CM) and Matthew Merighi (MM) is below.

MM: We’re here with Admiral Michel, the Vice Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard. Admiral Michel, thank you for joining us on Sea Control today.

CM: Thanks for having me, I appreciate it.

MM: As is Sea Control tradition, please introduce yourself, tell us a little bit about your background, how you came to be where you are now, and what were the main events that happened along the way.

CM: Sure I’m the Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard, so I’m the number two person at the Coast Guard. I assist the Commandant. We’re in this great organization called the U.S. Coast Guard which has about 40,000 active duty members, plus reserve, plus a cadre of auxiliaries which help us out. Really, we are an agency with global responsibilities so the Commandant needs somebody like me to run this entire enterprise.

I’m the chief operations officer and also the chief acquisitions officer, and a bunch of other things that make this the world’s best Coast Guard. I think I’ve got an interesting background, and I know you have a naval officer audience, but the Coast Guard is kind of unique in that we can become specialized officers but also retain our line credentials at the same time. So I’m a lawyer for the Coast Guard as well as an operator. I spent about half of my pre-flag officer career afloat and the other half as a lawyer which is kind of unusual now. I’ve been able to work all the way up the organization. According to my bio I’m the only 4-star officer in all the armed forces who’s also a career Judge Advocate (JAG) which is kind of an unusual thing, just a consequence of what I do. So I’ve got kind of a unique background with operations afloat and legal, and I’ve done some other things for the Coast Guard.

MM: So let’s talk for a minute about your role since you mentioned you’re the only four star JAG who has managed to make it to that level. But you’re also the first 4-star Coast Guard officer who is not the Commandant. So in terms of your day to day role, in doing acquisitions and operations, how have you transitioned the role of the Vice Commandant to being a 4-star? Have you noticed it being different or how has that gone?

CM: It’s different and in a good way. I think Congress chose to elevate this position from what has traditionally been a 3-star to a 4-star in recognition of the Coast Guard’s prominence and the need for another senior officer for all the diplomatic and representational duties we share. I know you mentioned the COO and the acquisition officer which have external aspects, but our work with all the elements of the defense establishment, the 4-star elevation gets you into different levels of engagements than as a 3-star. Same on the international scene. Bringing a 4-star on the table has a different flavor. I know to junior officers there doesn’t seem to be a difference between a 1-star and a 2-star, but there’s a big difference between a 3-star and a 4-star in a lot of events and I think it’s a reflection of the prominence and the credibility of the Coast Guard within the congressional leadership.

MM: So let’s talk then about your work with the other services. What is the Coast Guard’s role in the maritime security space, particularly how it organizes and how it works with the other services? Also how does the Coast Guard pursue its unique mission set of being a military service and law enforcement agency?

CM: For your listeners who aren’t familiar with the Coast Guard we are a member of the armed forces at all times but at the exact same time we have the responsibilities of a law enforcement, regulatory, humanitarian, environmental protection, navigation, and communication agency and much more. These are all things we bring to the fight at the same times. So when you are talking about the world of threats we have an oar in the water on the symmetric threats such as nation state actors and on any given day a number of our ships are chopped to combatant commanders.

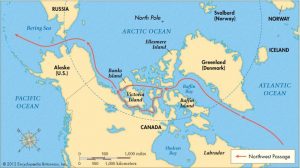

Today, without giving the numbers, we have a number of ships with U.S. Southern Command in a detection/monitoring mission. We have six patrol boats in the Persian Gulf who are chopped to CENTCOM. A lot of times we have an icebreaker chopped to PACOM for deep freeze missions. We participate in RIMPAC and other exercises with DoD. We’ve got responsibilities on the symmetric side and on any given day there are Coast Guard people on every continent. Some small boat units and some major units. We are required by statute to operate as a specialized service in the Navy during time of war when the president directs. So our equipment is interoperable with DoD partners. Many aspects of our operations are woven together.

At the same time the Coast Guard has the job of law enforcement agency, regulatory and many other things. A lot of our effort is engaged in that, regulation of shipping, making sure cargo entering the nation’s ports is secure, making sure inland waterways, which is a whole highway vital for economies to operate, works together. We deal with the navigation on the Great Lakes, we conduct polar operations, protect fisheries, you’ll probably see us on the Weather Channel rescuing people in storms and other things. And we’re a unique agency that operates in the whole threat spectrum from symmetric actors, to terrorists, to criminals, to regulator violations to mom-and-pop boaters getting in trouble, to natural disasters, hurricanes, earthquakes, and oil spills. All with 40,000 people, smaller than the New York Police Department.

MM: That’s obviously hard to accomplish with 40,000 people and a very broad mission set. One that many of our listeners know some of the aspects but not all. So from your position looking at those different challenges in maritime security and Coast Guard missions, which of those threats are the ones that interest you the most, that you think are going to be the most potent or the potential to evolve to be pressing to our national security? Is it terrorism, criminal elements, migration, what are sort of the things you’re keeping an eye on?

CM: On the symmetric side of the house, not counting DPRK, let’s take a look at the threats to freedom of navigation that are being asserted by nation states right now, whether its Russian navigation restrictions in the Northern Sea Route or things going on in the South China Sea. That increasing world of these unlawful navigation restrictions concern me quite a bit. I think freedom of the seas for national security and movement of commerce is absolutely critical. The Coast Guard plays a role in all those freedom of navigation assertions whether being the lead role of the international maritime organization where we champion these rights or others. Those concern me a lot on the symmetric side.

On the asymmetric side, we have a lot of terrorists out there doing a lot of bad things. Some of them have shown the ability to operate in maritime spaces. Maritime is also a logical route for moving goods or terrorists themselves, we monitor that extremely carefully. Post September 11th, we have established a layered security regime that involves ports, ships, and a whole network of connections as we deal with those asymmetric threats that may harm this nation. Then we have a bunch of other challenges such as competition for resources whether it’s unlawful claims to hydrocarbon jurisdiction, fisheries poaching, or a whole other world to work with. I get concerned with transnational criminal organizations in the Western Hemisphere due to their increasing sophistication. They put out semi-submersible vessels with over 3000 mile ranges. That means they can carry 7-10 metric tons of any product from South America to Africa almost undetected. Their ability to impact the lives of people in the Western Hemisphere, they create a large homicide rates, instability which is driving migration which is driving instability. I worry about that whole problem set.

Then when is the next black swan event such as an oil spill or a major hurricane or earthquake which we have responsibilities for. It really is a world of threats and it requires a very agile agency to have the capabilities and capacities and authorities to deal with this range of threats. Whether symmetric nations, law enforcement challenges, terrorists, and then the big one in my wheelhouse that surprised me the most is cybersecurity. You wouldn’t think the Coast Guard wouldn’t be that involved but we are. We are a member of DoD Information Network, so we have own cyber defense challenges. We also explore how to use cyber to better enable our mission sets. And lastly, we are the agency charged with the regulatory responsibility for an increasingly automated port and shipping industry.

You may have seen that we had a major attack on Maersk shipping and ports that shut them down for a while. The entire delivery chain was subject to a cyber attack and that concerns us because that industry is a model of efficiency; because it is reliant on the internet and all the goodness of that. And every time you bring in a new navigation, communication system, etc. that replaces a human which you plug into the internet, it creates vulnerabilities. That is probably my most challenging task to create an agency that can operate in that space while that space is an active operational battlespace.

MM: Let’s dive deeper into the cyber issue. When I was doing some research before coming here, I saw you had given some talks on cyber and it surprised me just as much as it did about how crucial that realm is to the Coast Guard. Can you walk us through what happened to Maersk, it was Petya right?

CM: Yes, it was a Petya variant.

MM: So walk us through what happened, not just the basics but how the Coast Guard got involved and what you learned about how the Coast Guard needs to prepare for and how you’re going to get in front of it.

CM: First of all, we’ve got a good partner in Maersk. We do have authority to mandate reporting from certain partners, but they are a responsible party who brought this to our attention. They actually sit on a lot of our Area Maritime Security Committees (AMSCs). The Coast Guard Captain of the Port for each of the nation’s 361 major ports is designated as a Federal Maritime Security Coordinator. He chairs a committee that brings together all federal, state, local and private entities to deal with maritime security because ports are very integrated. If you deal with one portion of the port it will impact another. So getting a holistic approach to this problem set is critical. Most AMSC’s perform that function.

So this report was brought through the AMSCs. We took a look at it from a security perspective with Maersk. This was not a government-owned system. It was privately owned. The Coast Guard has mandatory security regulations on the physical security side, such as access control. On the cyber side we have some voluntary guidance but we have no imposed standards for shipping or port facilities. So we are operating against that kind of legal backdrop. But we reached out to help Maersk as much as we could, to try and get their arms around what kind of attack they were dealing with, what kinds of systems, business, or industrial control systems. Without going into great detail, a large portion of their remediation was done by their business people.These were their business systems by and large. But that split between what is the responsibility to a nation from cyber attack is really complicated.

For example, for a Maersk port facility, they have certain requirements for access controls. And typically those are to keep trespassers off their property or maybe a terrorist or a criminal or something like that. But it’s typically not to keep out nation states. If a nation state wanted access to that port facility, we do not require them to hold off nation states. But think about this from a cyber perspective. That exact same security posture for that Maersk port facility. If a nation actually attacks their cyber infrastructure, who has the responsibility to defend against that? A private citizen, the government, an insurance or regulatory problem? There’s a bunch of ways to skin that cat, we’re gonna have to get our arms around this, where on the physical security side we have that pretty much covered. We know what territoriality is, we know what a nation state attack is, we know what international law is on that. It has a physicality aspect that were comfortable with and cyber is a different animal.

Every time you turn on your cellphone it’s not just your friends and family; it’s hacktivists, criminals, nation states, all types of different actors, and what is your level of responsibility for that access system. It’s much broader, but as a lawyer I can tell you what I think will make a difference is creating common definitions and defining terms in this space then we can develop the norms we have in the physical world and get those into the cyber side. But we’re building this plane as it’s flying, there are real operations occurring in this space, good and bad.

The Coast Guard is kind of unique on this side, I think we talk from a position of not a large organization but authority-rich and when the Coast Guard was created it was not only for symmetric threats, i.e. nation states; the Coast Guard has been in every single war in the U.S., since the founding of the country, that has had a maritime component. But we also have this basket of other authorities that deal with law enforcement and regulatory and insurance challenges and all these other things. And you’re going to want to convert that same type of flexible nimble organization to cyber because when you get a cyber attack, where is it coming from? In the past if we knew it was from a nation state you know what the authorities were, if it was a criminal you know what the authority was. But now many times you get ambiguous threats. So when you need to align your authorities or responsibilities, you need a nimble agency like the Coast Guard, or the National Guard who also has nimble authority to deal with these types of threats. I know that Alexander Hamilton founded the Coast Guard in 1790, but in many ways he was very cyber aware because he founded an organization that was very nimble with all these authorities.

MM: So a parallel challenge to that that you alluded to in the cyber domain which is the Coast Guard has a role in is protecting supply chains. There’s the cyber dimension but there are also similar challenges to physical aspects too. Tell us a little bit about what the Coast Guard’s role is now and will be in the future for U.S. supply chain security

CM: So it’s related to what I said before. We built this wondrous supply chain that is the marvel of the world, and it gets better every day, with the just-in-time delivery of products, all overseen by this integrated IT that makes all this stuff happen. Monitoring containers from the time it’s loaded, where it gets on, where it’s trans-shipped, all the way here. Its sequenced to get on the automated truck that carries it to the rail yard. The Coast Guard doesn’t own that entire supply chain. We basically own the part where it gets loaded and where it gets off and we have responsibilities for a certain amount reaching the port.

When you look at negotiation in international ship port facility security code at the International Maritime Organization (IMO), it was revolutionary for the IMO to reach off of the ship onto the port. Bringing that port infrastructure into the security realm and our domestic legislation does the same thing. But other agencies such as Customs and Border Protection (CBP) with their lading rules and their electronic manifesting, cargo tracking, container security initiative, CTPAT, basically a partnership against terrorism that is voluntary and allows shippers to become trusted shippers. It’s a combination of things that’s going to protect this security chain. A lot of it resides on the side of the shippers but part of it is the government too. Where they are ladened on the ships, what the security arrangement at the port, on the ship and on the other end, how it reaches its intermode of transportation, all of which has a cyber element because it is all on network IT. So it’s a combination of both physical and cyber security.

I deal with issues like, should all containers be physically opened? I think if anyone who has asked that question has never been to the port of L.A.-Long Beach (LALB) and seen the vastness of the operation, and the majority of it brings goodness and essential economic strength, and what I will say is reduction techniques can be used to decrease the amount of physically going in and opening containers. But you can smartly address risk in that system through some more sophisticated methods.

MM: One of the most unique things I’m seeing about the Coast Guard is that you are referencing actions from private organizations and international partners which are done seamlessly with your own work. So what does the Coast Guard do that makes it able to effectively operationalize these public-private partnerships and international cooperation?

CM: First of all, the Coast Guard from its design in the very beginning, was made to operate with others. It started out as an anti-smuggling organization, but even then it was reaching to people on shore and to international components, so we have a great organizational reputation. Each one of our Coast Guard folks here has as part of their organizational DNA a natural bent to work with partners. We want to leverage our partners and I think it comes down to us being such a small organization with a lot of responsibilities. Authority rich with great people but not a lot of Coast Guard to go around. So we aren’t afraid to get our hands into cooperation at all.

Rarely do we reach for a fully organic Coast Guard solution which I think is rarity in government. Most government organizations say how are we going to build this, how much is it going to cost, etc. The Coast Guard mentality is: who can we work with to fulfill our goals? We’re more than comfortable with working with people. We have Coast Guard people in small numbers scatter around the government and around the world and they bring that organizational DNA of connecting with others. They bring that basket of authorities and they bring that organizational reputation of being a good organization and partner.

Private industry loves it. Many times they don’t want regulations; they want assistance and they want a level playing field so that they can remain competitive. Many times they want to shoulder that responsibility themselves. In cyber, I think many of the solutions are going to come from private industry with government guidance. And I think that softer approach is how the CG solves problems and thats the way we’ve been from the very beginning. We’re a natural integrator and typically our first grab is not to build our own organization, which is unusual for a regulatory organization.

MM: One of the challenges I’ve seen personally, one which Admiral Stavridis at the Fletcher school has talked about and the Stimson Center has been doing some work on, is the role of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing as an economic and national security threat. Walk us through what you see the future of fishing enforcement will look like and what the Coast Guard’s role will be.

CM: For many people, protein from the ocean is their main source of food. And I can tell you when people can’t eat then bad things happen. For a lot of countries it is an existential threat, especially these small Pacific island nations that rely on fishing for sustenance. This is a huge challenge and I can tell you there is a huge competition for resources.

Fisheries is just one example. Fishing technology has advanced so fast that boats can clean out all the protein they need and then get out of dodge and sell their products with no eye on sustainable fisheries, which really is a tragedy of the commons. Part of the reason they can do this is that there is no eye in the sky on oceans with maritime awareness. So it is a governance challenge too, the legal regimes. And legal regimes have been put into place. In fact, Congress recently took some action. One of the unique challenges of IUU fishing that makes it particularly difficult to deal with is you have to have a viable at-sea enforcement regime. You can’t deal with it through ports. A fisherman can choose where to put his catch or where he wants to trans-ship it, so by the time it gets to a port official, it is hard to be able to take action. I’m not saying port enforcement officials don’t have that in place; but if you don’t have that enforcement presence at sea to catch them in the act, take their boat, take their catch, you’re just not going to get there. There’s not enough law enforcement assets, so it’s a awareness challenges. I think that is where you’re going to see some of the most innovative things done will be in maritime domain awareness.

So the use of commercial overhead is something we’ve talked about before with sophisticated sensors to alert law enforcement regarding closed areas. To provide countries with some ability, even if it’s a shared ability, to do at-sea law enforcement. Some will get together to share an asset or maybe use a ship-rider program which we’ve done before to spread their authorities. I think that in combination with a smart look of the space itself is going to be a major way forward. I think transponders offer a lot too; to use transponders to sort out legitimate fishers from illegitimate fishers, deal with dark vessels and non-emitters, which we’re getting better at every day with sensors becoming cheaper. That is something else that we can do.

I’m of two minds of this thing. There are lots of countries where their fishers are doing illegal activities and I’m not convinced that all of them are doing everything they can to police their fishing fleet. At the same time, I’m optimistic about technology, more sophisticated law enforcement regimes that may balance this. And I think there is a place for port enforcement on this, although as I said you really can’t completely deal with it without at-sea enforcement.

MM: Since we’re reaching the end of our interview, we will conclude with the same conclusion with most of our episodes. Tell us about what you have been reading recently, what are the main articles and books that have caught your eye.

CM: This is going to sound pretty boring, but I’ve been reading a lot of energy-related publications because I believe the world is undergoing a geostrategic shift in the balance of power in energy and related products. Although it wasn’t covered very well in the press, President Trump mentioned not only energy independence for this country but also energy dominance. I would encourage people to examine that topic because that is super important.

This country has been energy dependent, in varying degrees, on lots of different players in the past, but it may not be in the future. We have liquefied natural gases leaving this country in export quantities both through the expanded Panama Canal to Asian nations which are consuming that. President Trump in his speech to Poland highlighted that a cargo of U.S. liquefied natural gas was delivered to Poland for the first time, which has huge geopolitical ramifications in regards to Russia. The combination of two simple technologies, horizontal drilling and fracking, has the potential of becoming a major energy supplier which will impact the world geopolitical climate. Whether it’s countries in the Middle East or South America who’ve relied on their own version of energy dominance, I see that being chipped away.

As a Coast Guardsman this is hugely relevant, because if energy is being exported by any means other than pipelines, it is moving by water and through the sophisticated shipping industry that moves products around in a global market. Once again, a just-in-time market, and we get movement of energy products in this country on inland waterways, offshore, arctic, you name it. These energy trends have the potential of reshaping the geopolitical globe that I grew up with. And I’m watching it very carefully and the Coast Guard is right in the middle of it because a lot of these products, unless they go by pipeline, move by water. And when you talk about products moving by water, you have the Coast Guard right in the middle of all that stuff.

MM: Thank you so much for your time, Admiral Michel. Best of luck with all of those diverse security challenges you have to deal with, and we’re all rooting for you.

CM: Great, proud to serve. Semper paratus.

Admiral Charles Michel is the 30th Vice Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Matthew Merighi is the Senior Producer of Sea Control.

Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.

Navy to talk about the Russian Navy and its latest developments.