By Max Stewart

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increased and discernable concern surrounding the possibility of an invasion of Taiwan by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The topic returned to prominence in the wake of the 2018 National Defense Strategy which described a China seeking “Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near-term and displacement of the United States to achieve global preeminence in the future.”1 In the years since, despite the increase in geopolitical tensions, mainstream debate, and the unofficial public statements of U.S. figures, the official policy of the United States remains “strategic ambiguity,” or an unwillingness to firmly commit to the military defense of Taiwan. This is the natural byproduct of the U.S.’s “One China Policy” built upon the Taiwan Relations Act, Three Joint Communiques, and the Six Assurances.2

What this means in practice is that in the event of a PRC attempt at coercive military unification with Taiwan, the Biden Administration would lack the explicit standing legal authorities to intervene that exist with congressionally ratified treaty allies outside the limited War Powers Act. As indications and warnings (I&W) of a possible cross-strait assault emerged, and as the invasion began, a robust and likely time-consuming interagency debate would occur within the White House, Pentagon, and on Capitol Hill.

This campaign analysis seeks to determine how long U.S. decision-makers can realistically have those debates before the PLA seizes Taipei and the window for effective intervention with military force has closed. It does so by employing analytical modeling, informed by historical data, to determine how long the Taiwanese can resist a Chinese invasion absent direct U.S. military intervention given best-case-scenario timelines for the PLA. That is to say in this campaign analysis, tactical and operational chance favors the PLA, and Taiwanese resistance is more similar to that of the brave but desperate 2014 Ukrainian military fighting in the Donbass than the more successful and combat credible 2022 Ukrainian military which halted a Russian invasion. What follows is not meant to be predictive, but rather cautionary, and presents the most stressing timeline for U.S. decision-makers. Any deviations from this scenario would only serve to elongate the timeline for the PLA’s campaign, thereby increasing the decision-making space for U.S. leadership.

Scenario “Road to War”

In the scenario used for this campaign analysis, at the conclusion of the October 2022 20th Party Congress, President Xi orders the PLA to complete the forceful (re)unification with Taiwan in the summer of 2023. PRC and PLA decision-makers view the summer months as the best window to launch a cross-strait invasion. This period encompasses the most favorable tidal conditions in the strait, the highest readiness of its conscript force, and has the ability to partially mask its large-scale force buildup with its normally held annual summer exercises.3,4 However, despite PRC outward messaging as to the normalcy of the summer exercise, certain indicators over time will lead the U.S. Intelligence Community to assess with increasing confidence that an invasion is likely. As reported by John Culver with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, some of these indicators and warnings may include:

- Surging production in munitions.

- Actions to insulate its economy from the impact of sanctions.

- Freezes of foreign assets within China.

- Return of Chinese assets held in foreign states.

- Stockpiling of critical supplies and war-making materials.

- Psychological preparation of the Chinese populace for war.

- Large-scale movement of ships, planes, and armored vehicles.

- General mobilization to include “stop-loss” of conscripts.5

With the combination of factors above, initiated in the wake of the 20th Party Congress, it can be assessed that the U.S. and Taiwan would begin seeing I&W of a possible invasion six months before its execution. For the analysis that follows, the U.S. and Taiwan modify their assessments from “invasion possible” to “invasion likely” one month prior to the cross-strait assault. This is a generous assumption for China, as during the Russian invasion of Ukraine the U.S. had reliable intelligence of a coming invasion nearly five months before its start.6 In this PLA-best-case scenario, a combination of PRC operational security, messaging, misinformation, and military deception enables this surprise.

PRC Concept of Operations and Desired Endstate

The scenario below is broken down into distinct phases roughly corresponding to the anticipated concept of operations envisioned by various PLA scholars.7 The evaluated phases for this analysis will be:

- Joint Firepower Strike Operation (JFSO), Outlying Island Seizure, and Mine Warfare

- Strait Crossing and Initial Landing

- Securing the Lodgment and Building up the Breakout Force

- Breakout, Advance, and Seizure of Taipei

The desired endstate for the PLA is the complete seizure of Taipei and the inability for Taiwanese forces south of the city to counterattack and liberate the capital. The desired endstate for the PRC is dislocation, dissolution, or capitulation of the Republic of China (ROC) government and successful (re)unification of the island with the mainland before U.S. intervention can occur. While it is conceivable that the PRC may choose to isolate rather than seize the capital city, in this evaluated scenario, the PRC seeks to avoid a prolonged siege and has determined that once they seize Taipei, the credible threat of immediate U.S. intervention will end. In order to achieve this objective, the PRC has placed every emphasis on speed in its invasion, while also opting not to take preemptive action against U.S. bases and stations in the Western Pacific, knowing such an action would likely galvanize the U.S. public and provoke an immediate response.

Joint Firepower Strike Operation, Island Seizures, and Mine Warfare

Campaign Day 0 – Day 15

The PRC campaign against Taiwan will begin with what in PLA doctrine refers to as the JFSO. “According to the PLA textbook Science of Joint Operations, the purpose of the [JFSO] is to intimidate an adversary’s leadership and population, break its will to resist, and force it to abandon or reverse its strategic intentions.”8 These strikes would combine kinetic cruise and ballistic missiles and rocket artillery with non-kinetic cyber and electronic attack to systematically degrade Taiwanese command and control (C2), coastal artillery, ROC naval combatants, air defenses, and destroy much of the ROC Air Force (ROCAF) on the ground. Effective Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) here would be critical to enable the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) to establish air superiority over the island as well as provide their own strike capabilities in support of the JFSO.9

Because in the scenario the PLA has determined that speed is of the essence to close the window on U.S. intervention, the JFSO assessed will be time-based vice conditions-based, using what some PLA scholars believe to be the desired campaign length of 15 days.10 According to Ian Easton,

“Chinese writings do not at all appear comfortable with the idea of blockading and bombing Taiwan for an extended period of time… the longer China blockaded and bombed Taiwan, the more likely it would be that the United States and other democracies would decide to enter the war. Chinese doctrine calls for short but intense strikes on Taiwan to secure localized control over the airwaves, airspace, and seascapes. Once these were in hand, it is anticipated that the campaign would shift gears to focus on surprise landings.”11

In this evaluation the PLA will commence their cross-strait invasion on Day 15, viewing the risks of incomplete shaping of Taiwanese defense as more acceptable than the risk of providing U.S. decision-makers time to choose intervention and mobilize forces. The following assessment will primarily focus on three areas of the JFSO: Destruction of anti-ship cruise missiles, SEAD, and destruction of the ROCAF. While the PLA’s Strategic Support Force (SSF), in accordance with their Systems Confrontation and Destruction doctrine, will also conduct extensive cyberattacks during this period to “completely destroy the enemy’s command and control network, communication network, and computer systems of weapons and equipment,” these operations are not modeled in this scenario, but do support the overall analysis’s PLA-best-case-scenario timelines by enabling actions in other domains.12

In recent years, Taiwan has significantly increased both its quantity of anti-ship missiles (ASMs) as well as diversified their firing units from ground-based launchers to air- and sea-launched systems. Amongst its ground-based forces, it had roughly 20 Hsiung Feng III missile launchers in 2020, with plans for 70 more in 2023. For this scenario, the ROC fields half of the new launchers by the time of invasion. This brings total ASM launchers to 55. With an average of 490 missiles built a year by 2023, there will be no shortage of munitions to target a PLA invasion fleet.13 Additionally, Taiwan just purchased 100 Harpoon Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCM) launchers with 400 missiles, bringing the total number of ground-based platforms for the PLA to target up to 155 launchers.14 For this scenario, being a PLA best-case, ASMs on ROC Navy (ROCN) and ROCAF platforms will not be considered. The ROCN’s larger surface combatants, whose locations will be well known to the PLA at the outset of the conflict, are unlikely to survive the initial JFSO and be subject to the PLA’s first mover advantage. As naval battles are often shorter and more decisive than land battles, this will likely present an unrecoverable setback for the ROCN.15

Similarly, as other studies have found, most of the ROCAF will be destroyed either on the ground or in the air after during the bombardment. It is important to note that this can be done with an estimated 60 – 200 Short Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs).16 With an assessed SRBM inventory of roughly 1,000 missiles, this estimated expenditure is extreme reasonable even if as much as 50 percent of PLA missiles are kept in reserve for a possible counter-U.S. intervention operation.17 The few remaining ROCAF aircraft, limited to solely those planes operating out of the underground Jiashan Air Base, will likely be loaded for air-to-air combat rather than with air-launched Harpoon missiles.18

The PLA’s SEAD mission to destroy Taiwan’s Integrated Air Defenses (IADs) and hunt for Taiwanese mobile ASCM launchers however will be far more difficult than the strikes against the ROCN and ROCAF. Due to the mobile nature of these launch platforms, the PLA will rely more heavily on aviation-delivered fires rather than their ground-based missile inventory to prosecute these targets. This can be exceedingly difficult. During Desert Storm, despite the U.S. having total air superiority over Iraq and Kuwait, it still had difficulty in identifying, tracking, targeting and destroying mobile forces on ground. In five weeks, the U.S. only managed to degrade 40 percent of Iraqi armor vice almost 95 percent of the largely stationary Iraqi IADs.19, 20 In Serbia by contrast, “NATO aviators sought to neutralize Serbia’s approximately 40 SA-3 and SA-6 area defense SAM launchers but were able to destroy only three launchers and ten air defense radar emitters after several thousand SEAD sorties and the expenditure of more than 1,000 [missiles].”21

Taiwanese mobile anti-ship and air defenses will further be able to utilize the urbanized nature of Taiwan to its advantage, using larger factories, warehouses, and tunnels to conceal themselves while reloading or avoiding detection. With those considerations, it is likely that with a constrained JFSO driven by time vice conditions, the PLA will find a still partially functional IAD network and certainly more than 100 ASM/ASCM launchers operable at the start of their invasion.

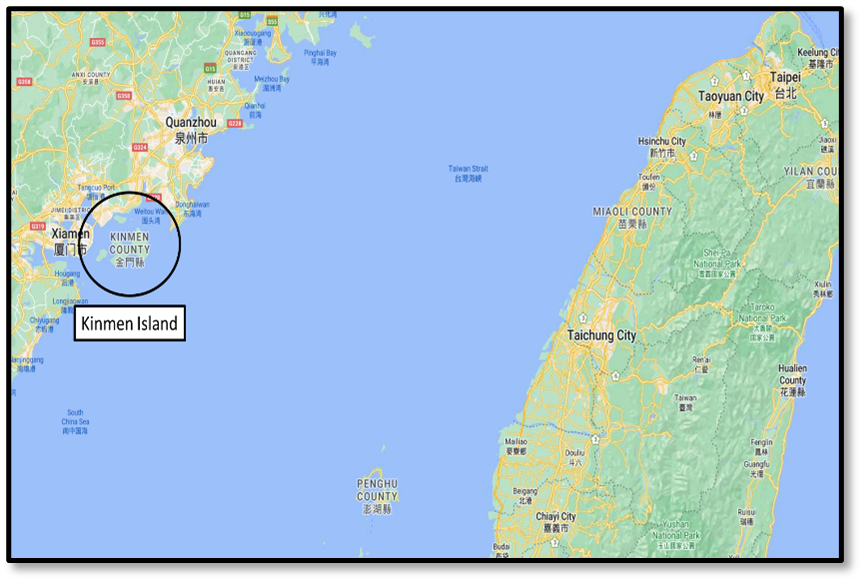

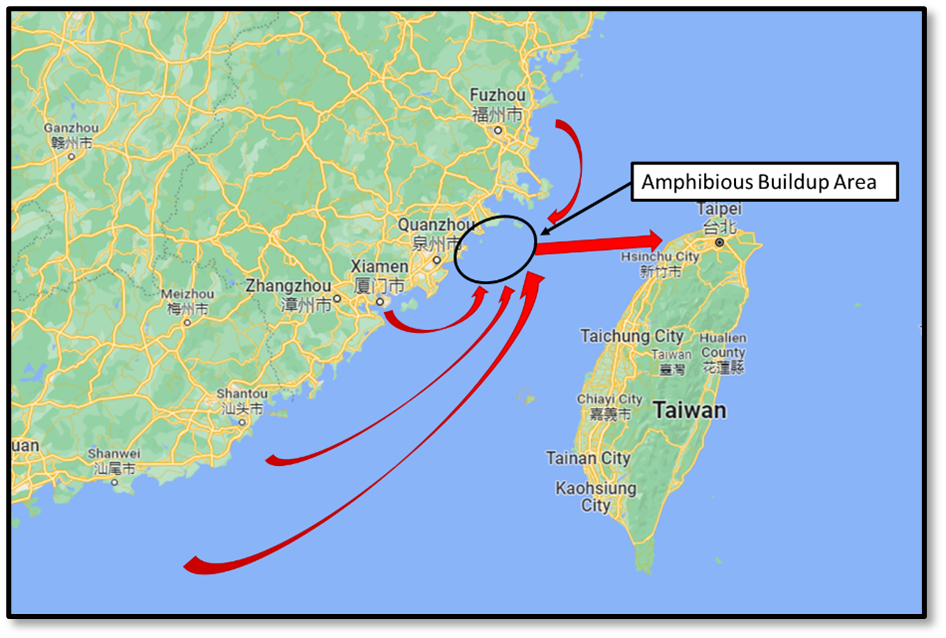

During the JFSO, the PRC will set the conditions for the cross-strait invasion by first seizing Taiwan’s outlying islands closest to the Chinese mainland. The PLA will employ Marine brigades already located in the Taiwan Straits Area to quickly seize Kinmen Island.22 This rapid action will not utilize any of the PLA Navy’s (PLAN’s) limited amphibious warfare ships. Rather the PLA Marines will employ their Type 05 amphibious assault vehicles to swim shore-to-shore across the four to nine miles separating Kinmen from mainland China.

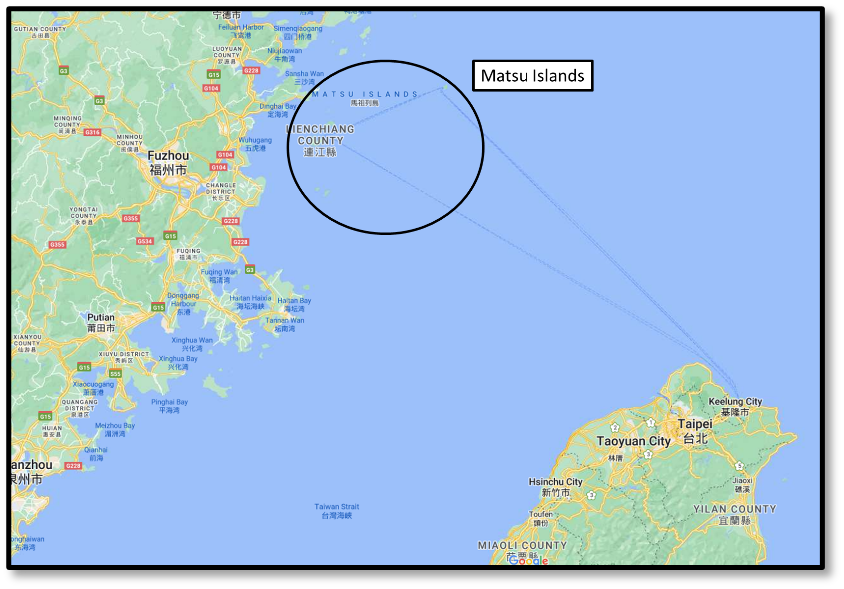

Similarly, the Matsu Islands, which stretch between 10 and 40 miles from mainland China, will also be seized during the JFSO utilizing airborne brigades supported by a follow-on air assault brigades from the Eastern Theater Command.23 These formations will be of limited utility during the initial assault on Taiwan itself due to the high likelihood of ROC IADs surviving the initial JFSO. However, the PLAAF’s SEAD mission against the smaller Matsu Islands would likely be successful enough to enable the deployment of paratroopers and heliborne forces. Both outlying island seizures can be support by shorter ranged shore-based artillery not otherwise required during the JFSO against Taiwan.

Naval mine warfare would also play a critical role in the events leading up to the PLA’s invasion of Taiwan. In this scenario, the ROC government does not begin immediately deploying naval mines into the strait at the determination that invasion is “likely” one month before the campaign begins. Rather, they assess that precipitously closing the Taiwan Strait to commercial maritime traffic via minelaying may incur international condemnation and jeopardize the goodwill they hope to generate amongst the international community. Because of this, only once the ROC government has determined that deterrence has failed and they can observe final PLA preparations that they begin their mining operations. In this scenario, that moment begins 72 hours prior to the start of the JFSO.

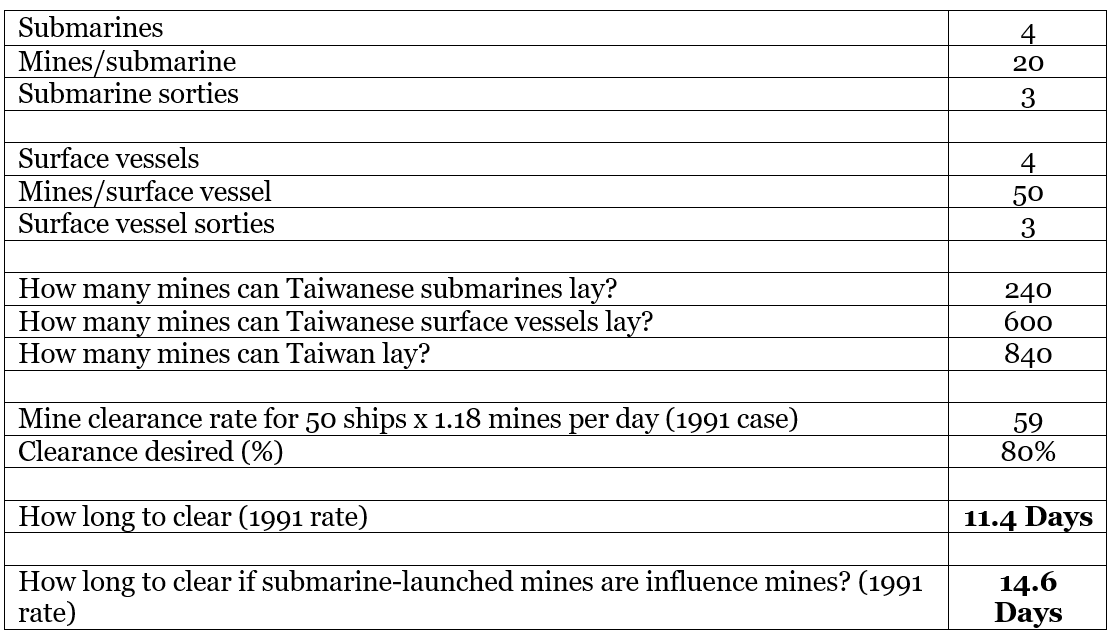

Taiwan has four indigenously build minelaying ships.24 While the mine magazine of each is unknown, these ships are roughly a third of the size of the Finnish Hämeenmaa-class minelayers, each capable of carrying roughly 150 mines.25 As such, for this campaign analysis each Taiwanese minelayer will be capable of carrying 50 mines per sortie. Additionally, Taiwan has four submarines: two Hai Shih-class subs and two Hai Lung-class subs.26 The Hai-Lung subs are roughly the same size as the Type 877 Kilo-class submarines assessed in Caitlin Talmadge’s “Closing Time,” while the Shih-class subs are two thirds of the size of the Kilos.27 With these considerations, the average mine payload for the four submarines will be set at 20 mines each. Each minelaying craft (submarine and surface ship) can conduct one minelaying sortie a day. Tasked with overcoming these explosive obstacles will be the 57 minesweepers of the PLAN. In the modelling conducted below, 50 vessels are available for clearance operations.28

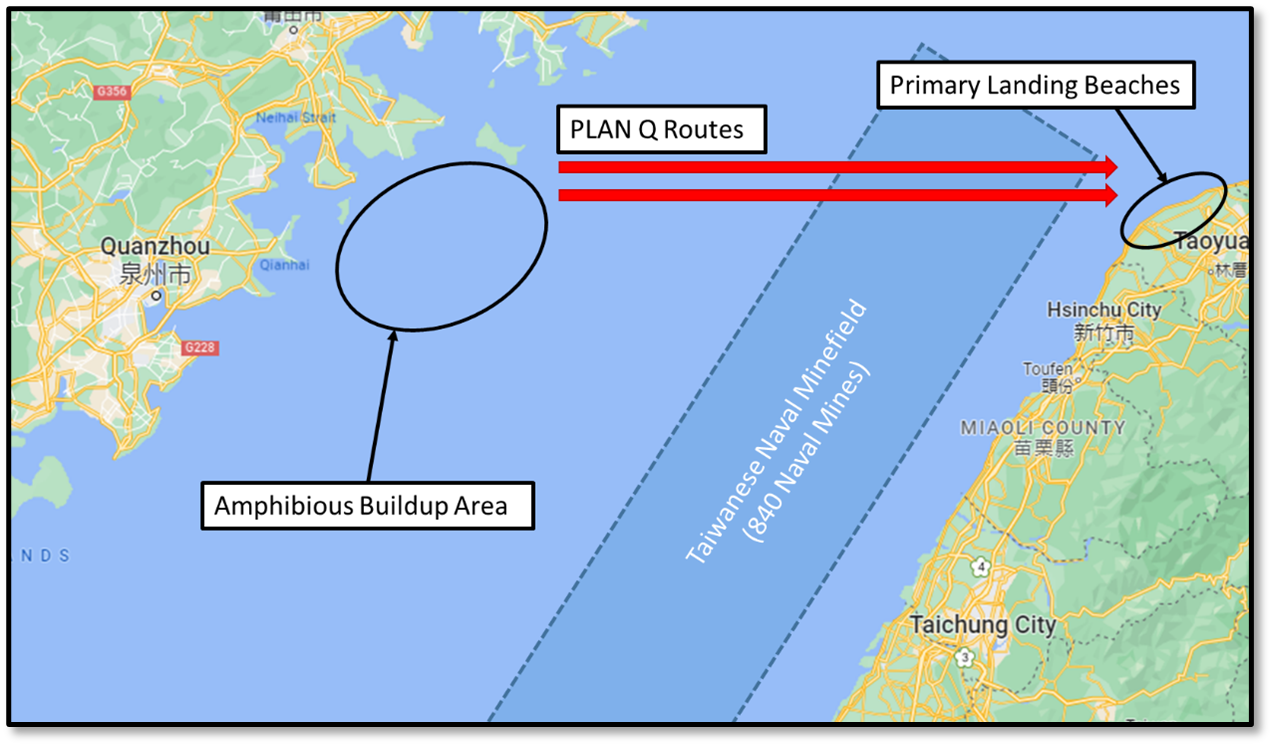

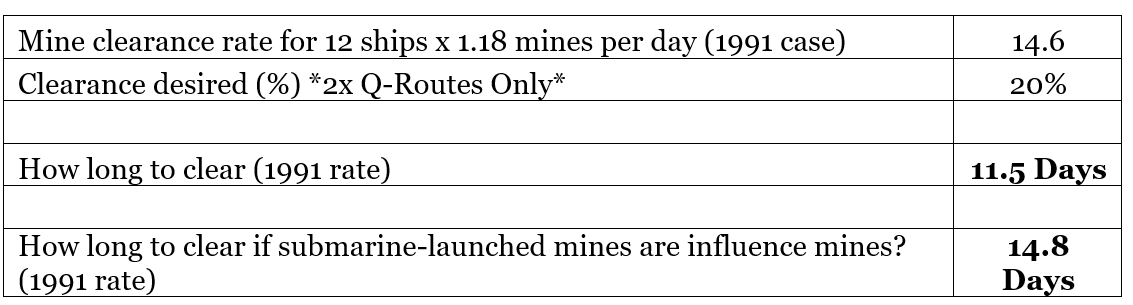

In the scenario, the PLAN begins conducting its mine clearing operations concurrently with the JFSO to allow the invasion force to immediately begin its cross-strait movement on Day 15. The model shows that the 50 minesweepers of the PLAN can clear 80 percent of the mines laid by the Taiwanese within the 15 days of the JFSO, even if they consist of the more difficult influence mines. It is important to note that this model does not depict PLAN minesweeper attrition at the hands of Taiwanese ASM/ASCMs. However, the model is built upon maximalist ends in the clearance of 80 percent of mines. Even with attrition, the PLAN could still clear two Q-routes for the invasion force within the 15 days of the JFSO with as few as 12 remaining minesweeping ships.29

Furthermore, because in this scenario the PLA has chosen to conduct a massed assault against only a single beachhead, while the Taiwanese will be forced to mine multiple approaches, the area required for clearance will be even smaller than in a larger scale scenario. This demonstrates that naval mine warfare, given Taiwan’s current minelaying capacity, is unlikely to play a critical component in the attrition of amphibs and other maritime lift platforms once the cross-strait invasion begins on Day 15. Furthermore, it shows the PLAN has tremendous flexibility in how it can choose to accomplish its endstate (clear routes for the invasion force) with different courses of action incurring various risk-to-force/risk-to-mission considerations.

Straits Crossing and Initial Landings

Campaign Day 15 – Day 20 (Landings Day 1 – 5)

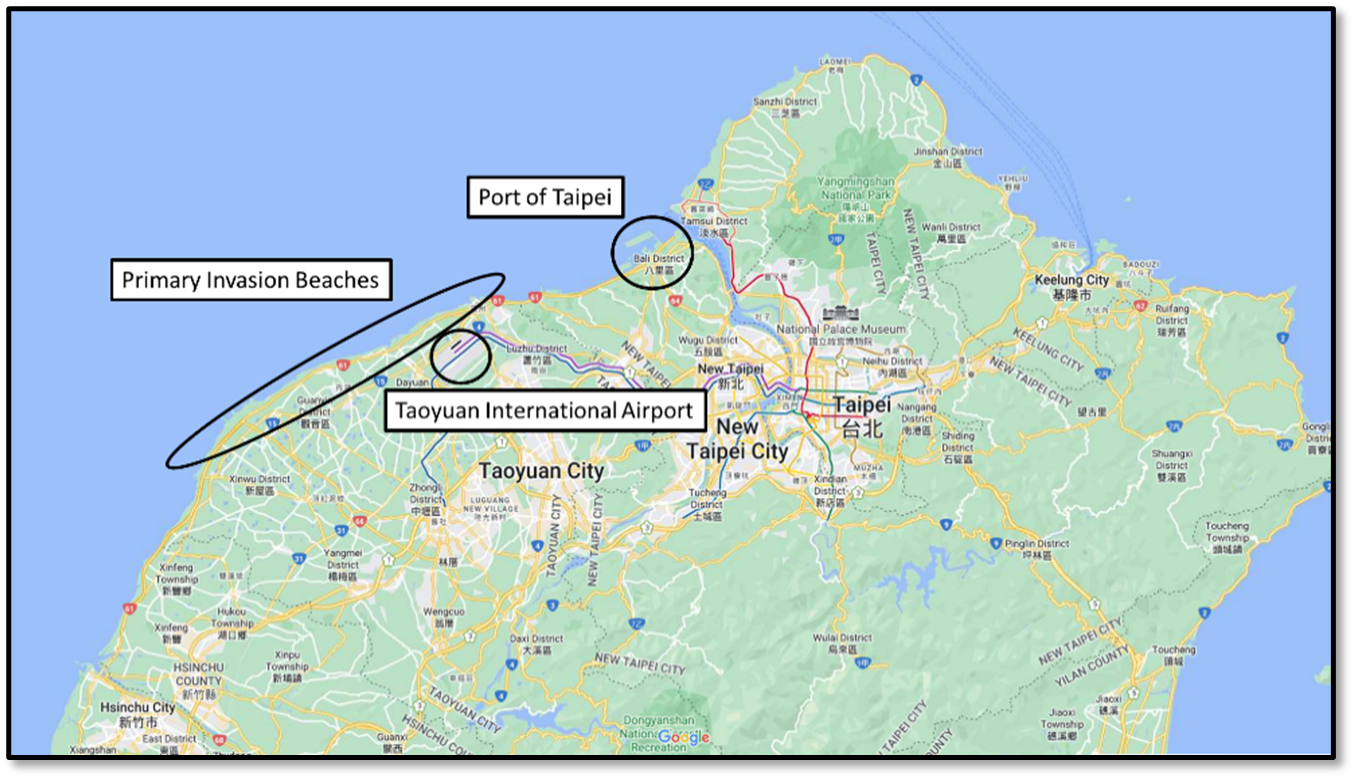

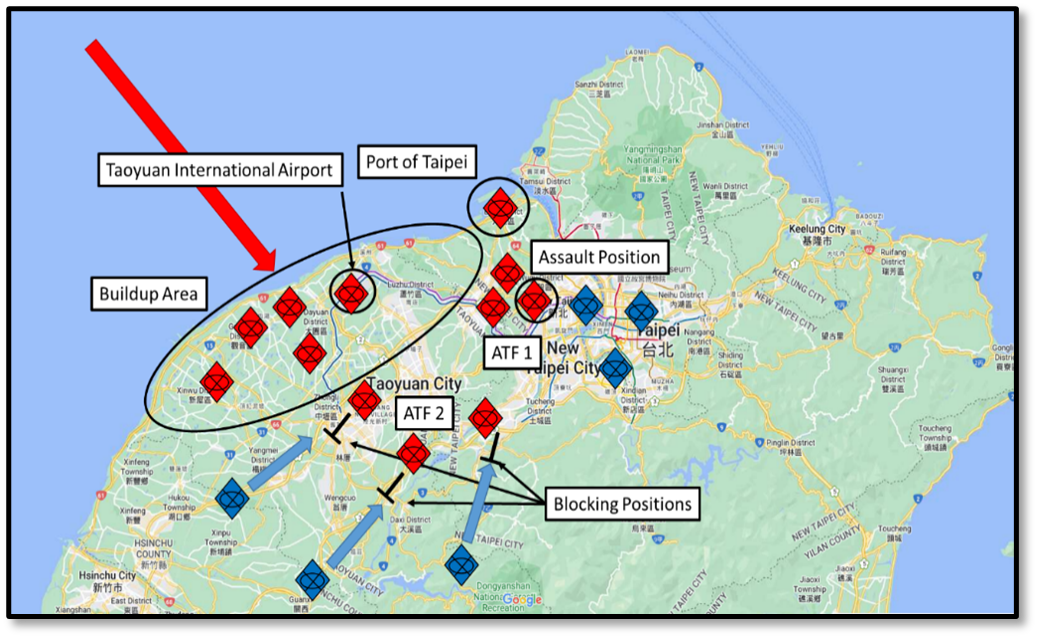

On Day 15 the PLA initiates the start of its cross-strait invasion of mainland Taiwan. The island has few suitable landing beaches, and the defending Taiwanese forces know them well. Furthermore, each of these beaches has prepared defensive positions, which would be reinforced over the weeks preceding the invasion. With these considerations, in this scenario the PLA has decided that instead of spreading limited amphibious, airborne, and Special Forces capacity across the whole of the island, they will mass their forces on a single beachhead directly adjacent to Taipei at the northernmost Western-facing beaches suitable for amphibious assault.30

By focusing their assault on only the northern portion of Taiwan, the PLAN can more easily mass the minesweepers and surface combatants required to protect the AWS and vulnerable Roll-On/Roll-Off (RORO) militarized commercial vessels. Similarly, this plan allows for the rapid buildup of ground combat power in order to avoid a lengthy overland campaign across the entire island. The proximity of the landing beaches to both a major industrial port and large international airport will further expedite the buildup of combat power and supplies, and the removal of casualties, during the invasion. By utilizing speed, intensity, and violence, the PLA hopes to isolate and rapidly seize Taipei and force the dislocation, dissolution, or capitulation of the ROC government.31

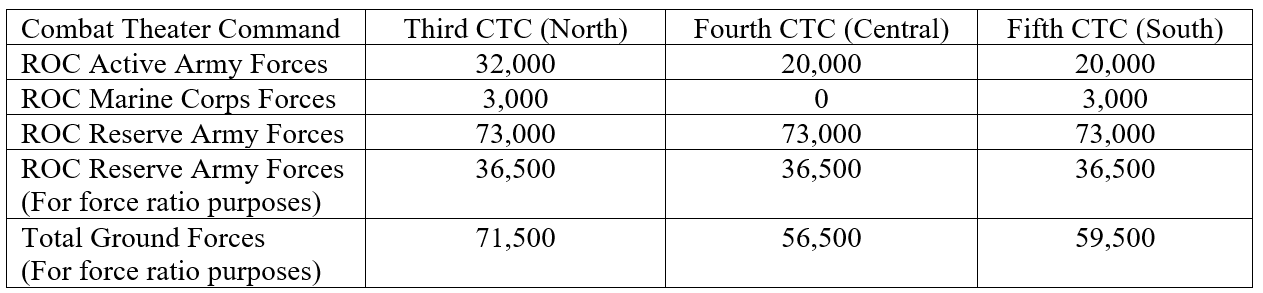

Facing this PLA invasion force will be the ROC Army and Marine Corps, comprised of both its active and reserve components. Taiwan’s active ground forces consist of 89,000 troops.32 The bulk of the Taiwanese Army is divided into three Army Corps spread across the northern, central, and southern portions of Taiwan. In the north of the country, the 32,000 soldiers of the 6th Army Corps is under the newly established joint headquarters the Third Combat Theater Command (CTC) and is responsible for the defense of Taipei and its surrounding areas. Their adjacent units are the 20,000 soldiers of the 10th Army Corps in the center of Taiwan under the Fourth CTC and the roughly 20,000 soldiers of the 8th Army Corps in the south under the Fifth CTC.33, 34 For the purposes of this analysis, the two ROC Marine Brigades are spread between the Third CTC co-located with the Army 6th Corps and the Fifth CTC co-located with the Army’s 8th Corps.35 The remaining ROC ground forces are located off mainland-Taiwan defending its various outlying islands.

The active force is furthermore augmented by questionably effective reserve formations. While Taiwan ostensibly has a large reserve force on paper, recent reports have revealed that the readiness, capability, and utility of this force is likely far below what would be required to repel a PLA invasion. As Paul Huang argues:

“They are called up at most once every two years by the Reserve Command to receive refresher training for five to seven days. In practice, such training rarely consists of more than just basic drills and a short practice session at the rifle range… And even if Taiwan somehow manages to muster dozens of fresh reserve infantry brigades before Chinese troops come ashore, Huang said they would be little more than cannon fodder consider how poorly the military has trained them in peacetime and the fact that there is not even a clear plan to fit them into the overall defense strategy… They exist for political, not military, reasons.”36

On paper Taiwan can muster as many as 2.3 million reservists. However, official government sources put the number of combat-ready reservists at closer to 300,000, though it should be noted that these “combat-ready” forces receive only the same limited training described in the quote above. Furthermore, a survey conducted by the Ministry of National Defense found that only 73 percent of Taiwanese would be willing to fight if Taiwan was invaded.37 For the scenario, it is assumed that while all 300,000 capable reservists are equipped and ready to fight, only 73 percent arrive at their muster stations, totaling 219,000 troops. These forces will be spread evenly between the three Army corps, totaling 73,000 additional reservists per corps. Furthermore, for force ratio considerations, and given the low-quality nature of these reserve formations, they are tabulated as .5 per soldier.

This brings the total number of defenders to the following:

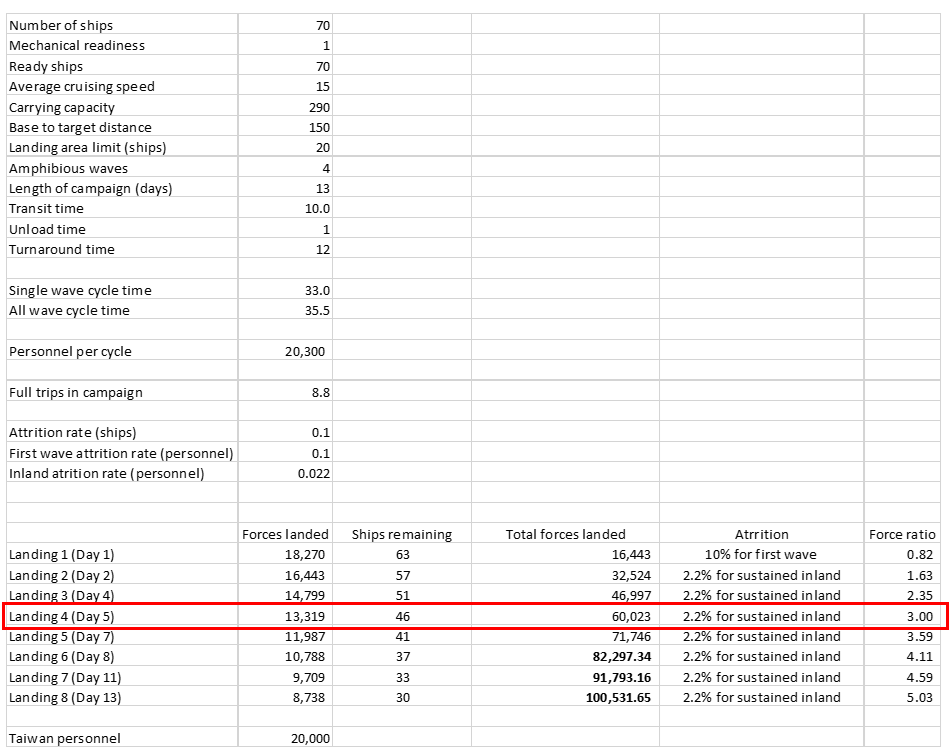

To achieve their initial beachhead, the PLAN will deploy its 70 amphibious ships of various types, capable of carrying roughly 20,000 troops in a single lift.38 These ships will depart their respective ports of embarkations, averaging roughly 150 miles from the targeted landing beaches, to aggregate with the minesweepers, cruisers, destroyers, and other surface combatants who will protect them on their 100-mile cross-strait movement. The primary task of these PLAN amphibs will be to land their embarked forces and rapidly return to mainland China to re-embark follow-on waves. Until the PLA secures the Port of Taipei, this will be the only method of building combat power ashore.

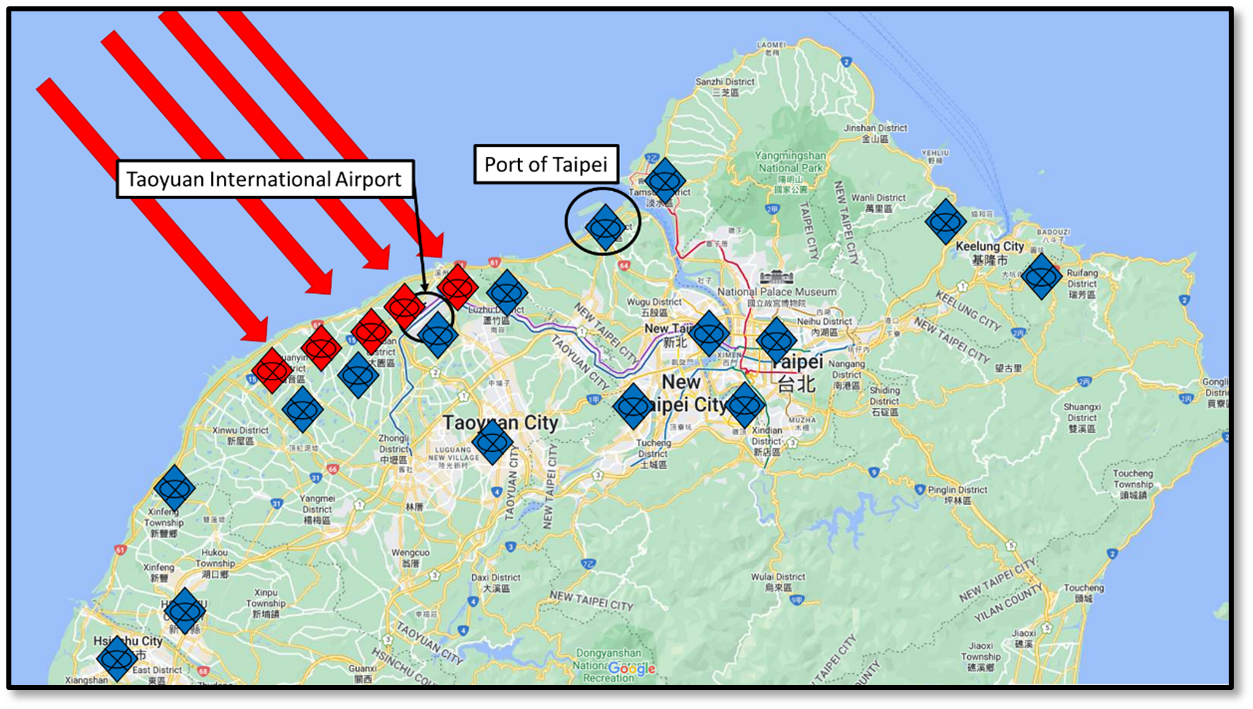

Based on the most up-to-date PLA doctrine on amphibious assault, “an individual amphibious combined arms battalion now likely has an expanded landing point width of 1.5 to 2 km, which would make the brigade landing section an approximately 3- to 4-km front.”39 The 20,000-man PLA initial landing force will be comprised of multiple brigades landing abreast. Facing them in the immediate area around the landing beaches will be roughly 20,000 troops from the Third CBT, with the remaining 51,500 troops spread out across the rest of the northern area of responsibility (AOR) to include the megacity of Taipei.

As the PLAN amphibs cross the strait, they will succumb to a roughly consistent 10% percent attrition based on the calculations provided in “A Question of Balance” depicting probability of hit based on remaining ASM/ASCMs who will themselves be attrited as their firing positions are revealed.40 PLA personnel casualties for the first wave are similarly depicted as 10 percent, with a sustained 2.2 percent once the fighting transitions inland.41 This results in a model that depicts it will take the PLA five days to meet the requisite force ratio of 3:1 to begin driving inland from their initial beachheads. During those first five days, the initial PLA landing forces will have to contend not only with the static defensive positions along the coast and immediately inland from the landing beaches, but also localized counterattacks from 6th Army Corps and the Marine brigade from the Third CTC. However, in this PLA-favoring scenario, these counterattacks will be severely degraded by the SSF attacks on the Taiwanese command and control networks, as well as massed fires from the mainland, both of which will cause not only the tactical degradation of the defenders, but also create significant psychological effects. Reinforcements from the adjacent Combat Theater Commands will be delayed for reasons that will be explained later in this analysis.

Securing the Lodgment and Building up the Breakout Force

Campaign Day 20 – 34 (Landings Day 5 – 19)

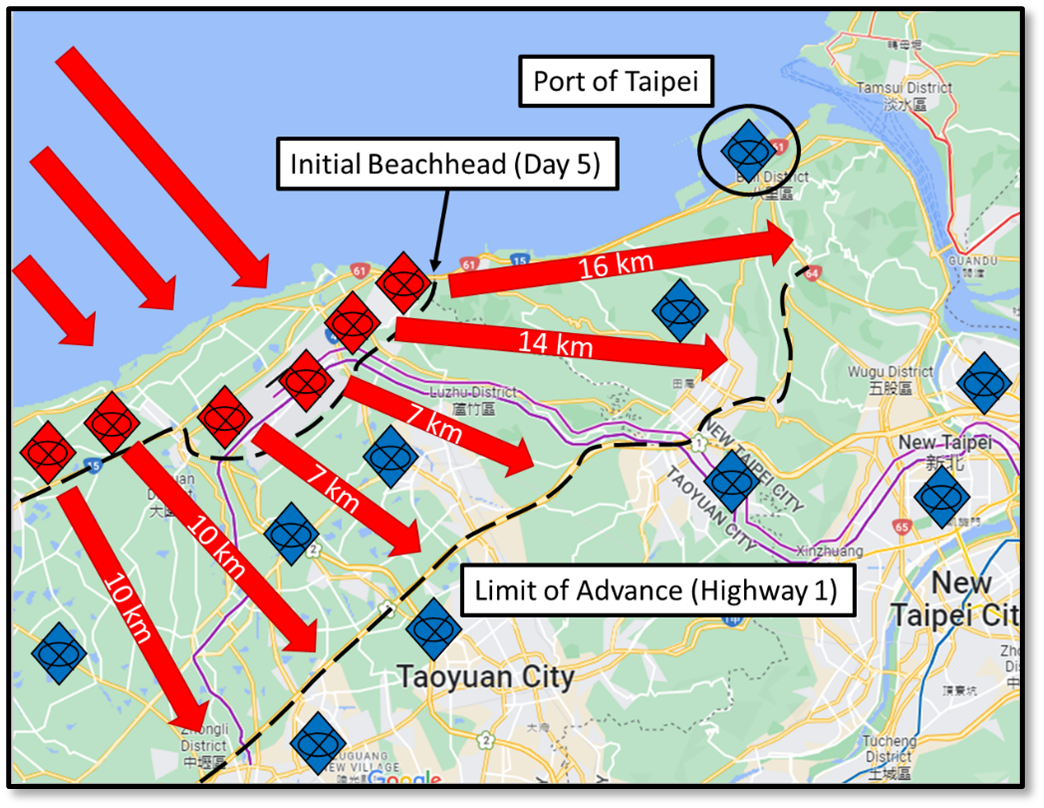

After the initial landings occur, the PLA will seek to rapidly expand its initial foothold on the island. This will occur on Day 5 of the invasion. Once the force ratio within the initial landing area reaches a 3:1 in favor of the PLA, the initial assault waves and their immediate reinforcements will push inland. This will allow them to secure key terrain and provide enough secure area to rapidly build up a force capable of breaking out of the initial lodgment and conduct the follow-on ground campaign. In this scenario, the PLA chooses to use the North-South running Highway 1 as their limit of advance tactical control measure and behind which to conduct their buildup. As a part of this operation to secure the lodgment, PLA amphibious forces will conduct a deliberate attack to secure the Port of Taipei located 16 km from the northern-most PLA unit on Day 5. The critical question in this phase will be how long the expected buildup of the breakout force will take given the ongoing attrition of PLA amphibs and other maritime lift vessels.

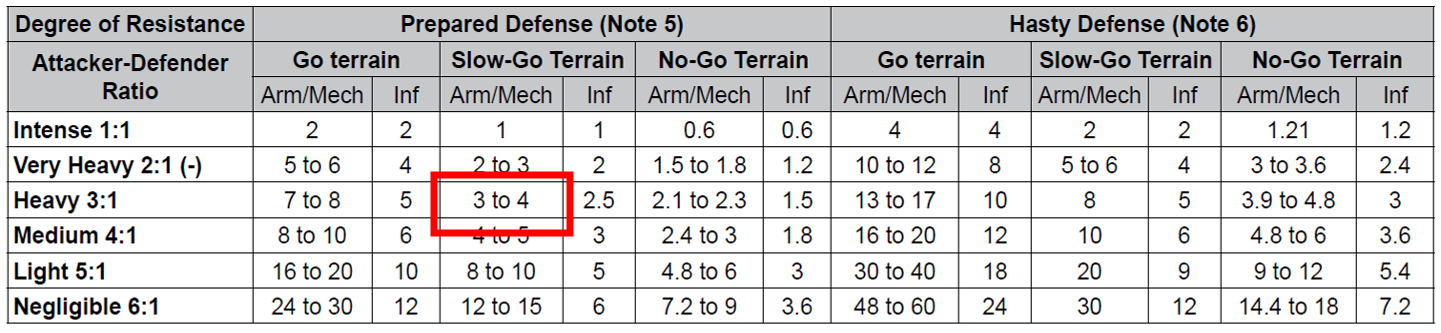

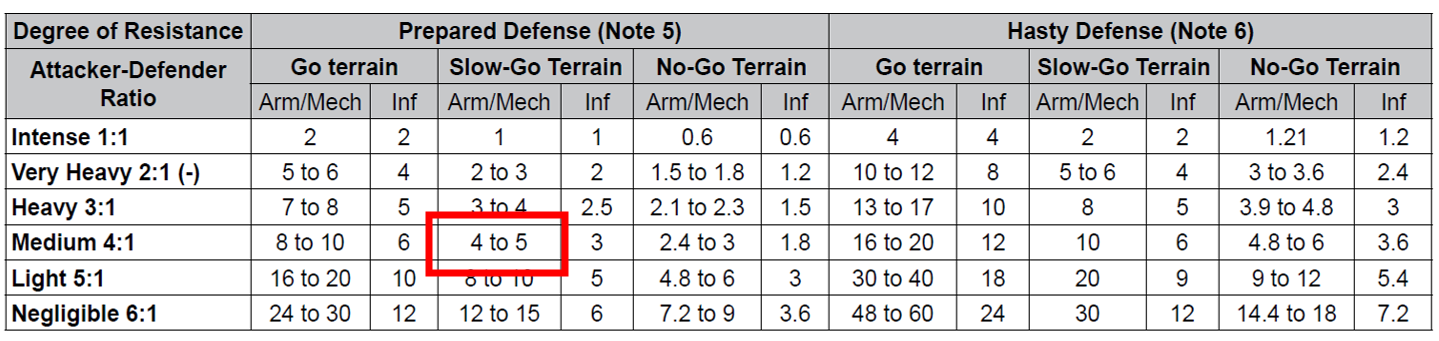

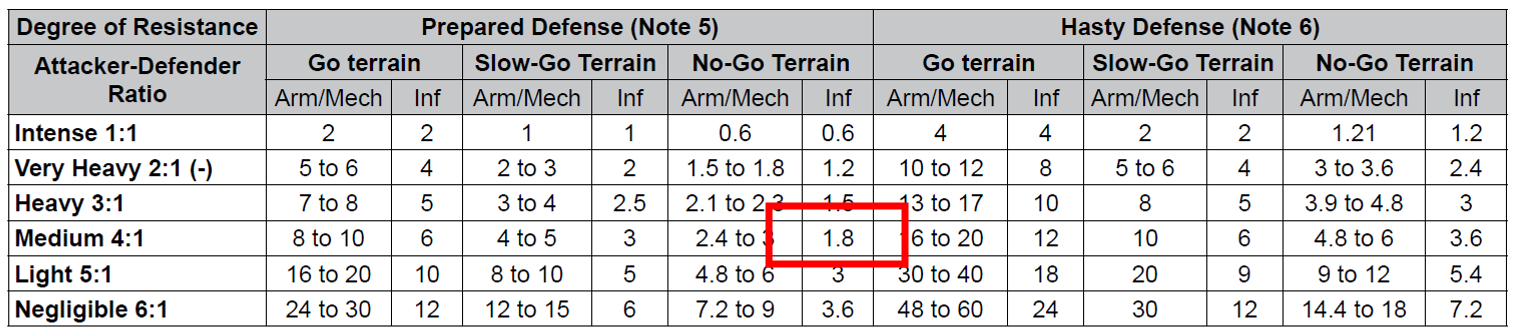

The seizure of the Port of Taipei will be a critical enabling action during this phase of the operation, allowing an increased throughput of PLA forces to be unloaded not just via ship-to-shore connectors, but also directly at the industrial dock facilities of the port. To determine how long it will take to secure the port as well as reach the limit of advance at Highway 1, the below chart will be utilized with the following factors. The localized force ratio is 3:1 is in favor of the PLA against Taiwanese forces occupying prepared defenses, with the hilly and urbanized terrain in the lodgment classified as “Slow-Go Terrain.” With these factors considered, it will take the PLA a total of 4 days to seize the port and secure its lodgment along the limit of advance, occurring on Day 9 of the invasion and 24 days after the start of the JFSO.42 It is important to note that this timeline would remain unchanged even if the PLA chose to seize the port with a direct amphibious or airborne assault, as those forces would still require relief from the assault elements landed at the primary landing beaches 16 km away.

In this PLA-favoring analysis it is assumed the invasion force can capture the port infrastructure intact and it is not sabotaged by its Taiwanese defenders or extensively damaged in the fighting. The seizure of the port will enable the PRC to begin ferrying additional forces across the strait in commercial vessels pressed into military service. These militarized RORO vessels are a key component of any invasion scenario and critical to the success of the land campaign.43 The PRC has spent years conducting the legal and regulatory requirements to ensure these vessels are available during times of war: “The 2003 Regulations on National Defense Mobilization of Civil Transport Resources, the 2010 National Defense Mobilization Law, and, most recently, the 2016 National Defense Transportation Law… allowed for the creation of National Defense Transportation Support Forces.”44 This provides the PLAN with a massive fleet of maritime transports to augment its own amphib inventory. In 2019, there were 3,987 PRC-flagged ships of 1,000 tons or greater in operation, with more than double that number of vessels being PRC-owned but foreign-flagged.45 Capt. Tom Shugart (ret.) evaluated the utility of this civilian maritime capacity during an invasion scenario and found the following:

“China’s military-associated roll-on/roll-off vessels could deliver more than 2,000,000 square feet of vehicles per day — more than four heavy brigades’ worth of equipment. Over time, this roll-on/roll-off civilian shipping alone could deliver seven full Group Armies with their associated brigades — likely more than 300,000 troops and their vehicles — in about 10 days.”46

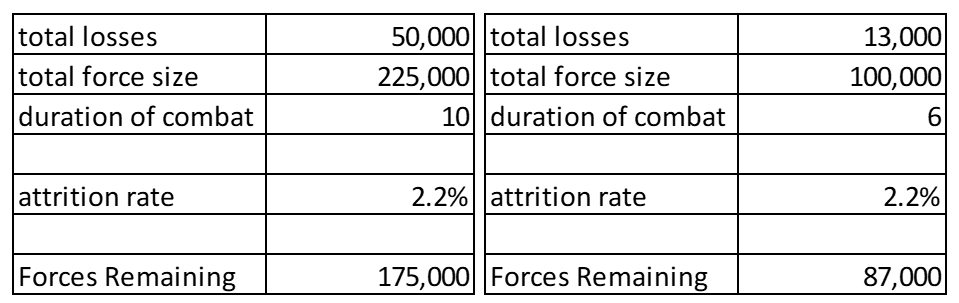

Without knowing the exact details of the computations used by Shugart (attrition, port availability, etc…) this campaign analysis will conservatively reduce the author’s original number by 25 percent, resulting in a total of 225,000 additional PLA forces arriving on mainland Taiwan 10 days after the seizure of the port on Day 19 of the landings.

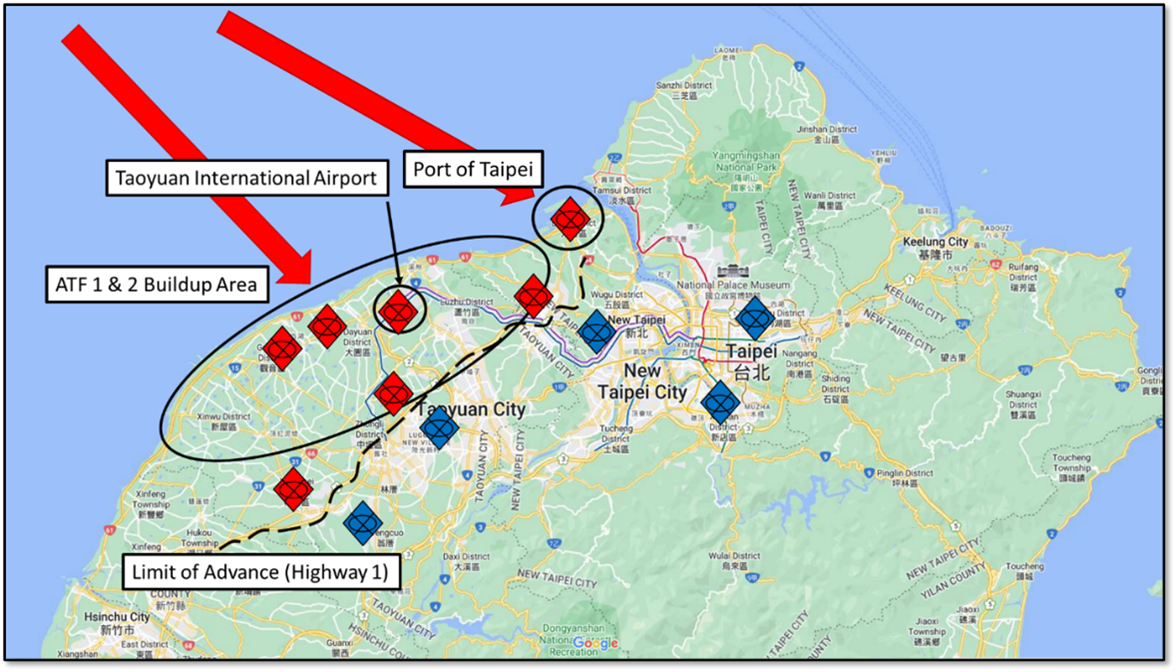

In the evaluated scenario, the PLAN suspends amphib lift operations after landing 8 on Day 13 once the amphib force has sustained over 50 percent attrition. With a sustained 2.2 percent attrition rate amongst both the initial forces and the troops landing at the port and driving forward to secure the lodgment, that results in a total of 262,000 PLA troops ashore on Day 19 of the landings, and 34 days since the start of the JFSO. It should be noted that while the Taoyuan International Airport is seized during the initial days of the landing, the air bridge established by the PLAAF will be utilized primarily for supplies and casualty evacuation. The PLA’s heavy ground forces will be brought to the island almost exclusively by ship to maintain unit integrity and avoid mass casualties in the air as a result of the lingering IAD threat.

The PLA cannot break out from their lodgment and seize Taipei until they amass two forces. The first is the city assault force, hereby referred to as Assault Task Force 1 (ATF 1). This is the force whose primary mission will be the intense urban fighting required to conduct the first megacity seizure operation in the history of warfare. Based on a Third CTC defensive force from 6th Army Corps and Marine brigade in and around the city comprising roughly 51,500 troops, ATF 1 will require a force of 206,000 to achieve the desirable 4:1 odds required for this type of heavy urban combat.

The second PLA force to amass prior to the breakout is the blocking force, hereby referred to as Assault Task Force 2 (ATF 2). ATF 2’s mission will be to establish blocking positions south to isolate Taipei and prevent Taiwanese reinforcements from entering the city. There are 116,000 Taiwanese active and reserve ground troops in Fourth and Fifth CTCs, responsible for the middle and southern portions of Taiwan, respectively. In this scenario, given the gravity of the situation, the Taiwanese military command chooses to displace two-thirds of those forces north to attempt to defeat the PLA assault on the capital. The remaining third are ordered to stay in place to prevent further landings around the island. Thus ATF 2 be required to defend against 76,500 Taiwanese soldiers in their counterattack towards Taipei. This requires the PLA to amass a blocking force of only 38,225 to deny the Taiwanese from achieving the 3:1 or better force ratio generally required for offensive operations.

This means the total required PLA breakout force, consisting of both the ATF 1 and ATF 2, will require 244,225 troops and is met by the 262,000 troops available from the above-calculated combination of amphib and commercial sealift deliveries by Day 19 of the landings. The remaining 17,750 PLA troops ashore not otherwise assigned to ATF 1 or ATF 2 will form a reserve capable of surging to either objective as required.

Breakout, Advance, and Seizure of Taipei

Campaign Day 34 – 46 (Landings Day 19 – 31)

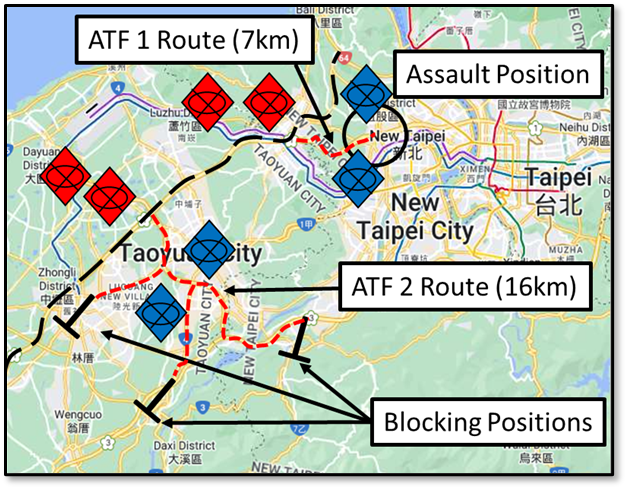

Once the PLA amasses the requisite number of forces, on Day 19 ATF 1 and ATF 2 would conduct their breakout from the initial lodgment. ATF 1 would follow Highway 1, which provides the most direct route towards the outskirts of Taipei. This route consists of a multi-lane highway with rolling hills on either side mixed with urbanized terrain. While the route offers an ostensibly high-speed avenue of approach, this will be partially negated by the hilly and urbanized terrain along the roadways which offers opportunities for easy-to-conceal defensive positions. The clearance of these defenses will slow the overall tempo of ATF 1, operating at the division level, as it fights down Highway 1 and adjacent routes for a total of 7 km to reach its assault positions at the outskirts of Taipei. Given the 4:1 forces ratios available, the prepared Taiwanese defenses, and “Slow-Go Terrain,” the likely rate of advance for ATF 1 will be 5 km a day, requiring a total of two days. Once this force arrives in its assault positions on Day 21, it will have to hold in place until ATF 2 has established its blocking position to the south and sets the conditions for the city’s seizure.

Simultaneously with ATF 1’s drive towards Taipei to its assault positions, ATF 2 would break out from the lodgment and push south to assume the blocking positions meant to isolate Taipei and prevent a Taiwanese counterattack from interfering with the seizure of the capital. In this PLA-favoring scenario, this ROC counterattack is delayed by a series of factors to include: the mistaken belief that the Third CTC can defend its own AOR, a fear of additional landings elsewhere on the island, the degradation of Taiwanese command and control networks by the Strategic Support Force, damage to the physical road infrastructure by the JFSO, and the mass exodus of Taipei’s millions of residents fleeing south causing both a humanitarian crisis as well as blocking all major routes north.

ATF 2’s drive will be opposed by the remaining Taiwanese forces originally tasked with defending the landing areas, who have been reduced from 20,000 to 8,500 after 2.2 percent attrition daily for 19 days of combat. This force, facing the 38,225 troops of ATF 2, create a better than 4:1 force ratio in favor of the advancing PLA fighting over similar ground as their counterparts in ATF 1. With these calculations, and with ATF 2 attacking at the division level with multiple brigades operating abreast along multiple routes, it will take ATF 2 just over three days to travel the 16 km to reach their blocking positions.

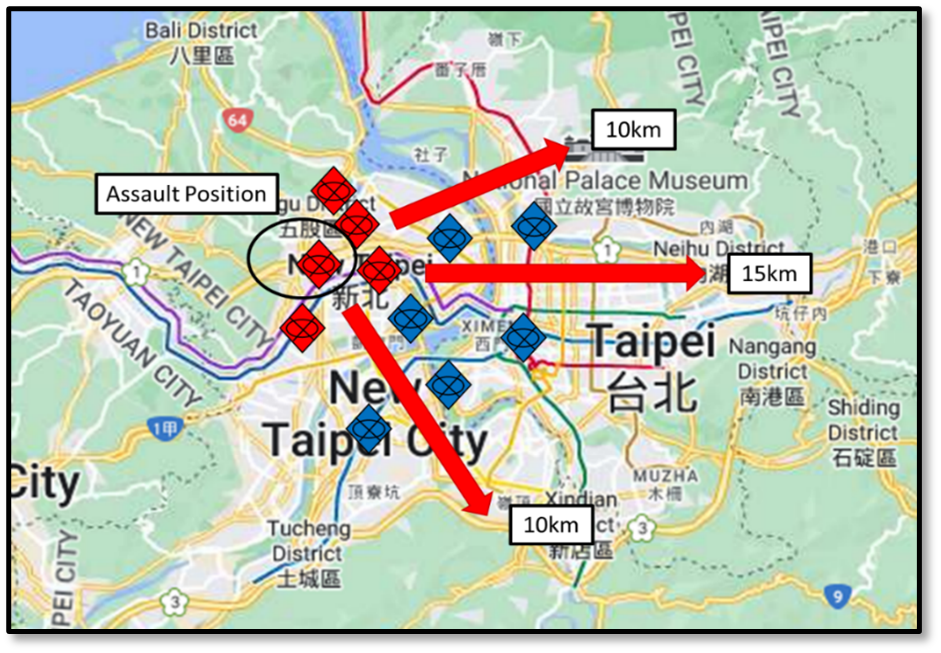

Once ATF 2 has successfully established its blocking positions and completed the isolation of Taipei on Day 22, and 37 days after the start of the JFSO, conditions will be set for ATF 1 to seize the city. PLA doctrine uses the rapid 2003 seizure of Baghdad and Fallujah in 2004 as the archetypal rapid urban assaults to emulate on Taiwan. This is especially important as during this final stage of the invasion, “time is of the essence—either to counter U.S. intervention or to minimize the window during which the international community might rally to the cause of the defender.”47 However, it should not be lost that Taipei and its surrounding area, comprised of over 10 million residents, is a megacity roughly twice the size (in terms of population) of Baghdad in 2003.48

ATF 1 conducted its breakout from the initial lodgment with 206,000 troops on Day 19, arrived at its assault positions outside Taipei on Day 21, and will begin its assault on the city on Day 22. With 2.2 percent of attrition suffered each day, ATF 1 will have 192,500 troops available to conduct their urban advance and will operate along a multi-division wide frontage. Facing them will be the remains of Third CTC’s ground forces, the 6th Army Corps and Marine brigade, originally numbering 51,500. This force has also been fighting since Day 19 with a 2.2 percent attrition rate, and by the time ATF 1 is ready to conduct its assault, will be comprised of 48,100 personnel. That results in a force ratio of or 4:1 in favor of the PLA.

Taipei, easily described as no-go terrain, consists of prepared defenses and is 15 km in distance across. While it is impossible to know the appetite ROC ground forces will have to subject their own capital to destruction, the PLA will seek every opportunity to achieve maximum speed. Whenever able they will attempt to maneuver to bypass and isolate enemy strongpoints in the dense urban terrain, rather than fight a lengthy siege block-by-block, in an attempt rapidly seize the city, close the window on U.S. intervention, and bringing about the end of the ROC government. With these factors considered, ATF 1 will take nine days to seize the entire city moving with multiple divisions abreast at the pace of their infantry advancing.

Policy Implications

While combat operations may continue on the island, the above modeling shows the practical window for U.S. intervention in a Taiwan invasion prior to the seizure of Taipei and the displacement, dissolution, or capitulation of the ROC government effectively closes 31 days after the initial landings. In the scenario, this is 46 days after the start of the JFSO and 76 days after the “invasion likely” assessment, though both of those times were based on educated assumptions vice data-backed models. As stated, this analysis is based on a best-case-scenario timelines for the PLA, in which the Taiwanese resistance they encounter is more akin to that demonstrated by the beleaguered 2014 version of the Ukrainian military vice its more successful 2022 descendant. U.S. policy in the short run must be focused on ensuring Taiwan’s military is not the overwhelmed, underequipped, and unprepared former, but rather the well-equipped, well trained, and motivated latter.

While U.S. leaders have limited ability to influence the Taiwanese will to fight, as seen in Ukraine, they can indirectly increase it by providing the island nation with the weapons and equipment it needs to conduct an asymmetrical defense in depth. These provisions should include mobile anti-air systems, land and naval mines, as well as the platforms to rapidly emplace them, and additional anti-ship missiles. Critically, the U.S. should also provide Taiwan with additional redundant, survivable, and hardened command and control capabilities to enable the efficacy of their battle networks and directly counter PLA attempts to implement a systems confrontation and destruction approach to the campaign.49 As seen with Starlink in Ukraine, ensuring a reliable command and control ability even in the face of a powerful adversary can prove decisive, and can serve to boost not only operational abilities, but also morale. These capabilities should be furnished either through expedited foreign military sales or the limited use of presidential drawdown authorities. All of these assets will serve to slow the advance of the PLA and thus elongate the decision-making space available to U.S. leaders.

To reduce that decision-making timeline, U.S. political leadership and the interagency must have the discussions and debates now, prior to crisis, about potential U.S. responses to various possible scenarios. These scenarios should include low-end contingencies such as the blockade of Taiwanese-administered islands in the South China Sea to high-end scenarios such as the invasion depicted above. While it is widely reported that the Department of Defense conducts planning and exercises to prepare for these eventualities, it is a dangerous misconception to believe the military can or will operate in isolation during a conflict between the PRC and U.S.

To rectify this, the administration should amend their priorities for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administered National Exercise Program (NEP) to include preparedness for major state-on-state conflict. The NEP conducts exercises incorporating the interagency, local and state leadership, non-governmental organizations, as well as the private sector and “is the primary national-level mechanism for examining and validating core capabilities across all preparedness mission areas… aligned to the Principals’ Strategic Priorities, which are determined by the Principals Committee of the National Security Council.”50 Per FEMA, the 2021-2022 Principal’s Strategic Priorities for the NEP include such topics as Continuity of Essential Functions, Cybersecurity, Economic Recovery and Resilience, National Security Emergencies and Catastrophic Incidents, and others.51

While all are important topics for the nation’s security, preparation and conduct of war should be added to the list and be the focus of a biennial national level exercise. Though it was recently reported that the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party conducted a wargame on a Taiwan invasion scenario, “the members of Congress took the role of the president’s national-security team” rather than wargaming their own legislative responsibilities.52 Encouraging congress and the interagency to realistically exercise their own expected roles and responsibilities in the lead up to crisis and during conflict will serve to expedite decision-making and will drastically, and perhaps decisively, improve the nation’s ability to respond.

Major Maxwell Stewart, USMC, is a Combat Engineer Officer and Northeast Asia Regional Area Officer. He is currently serving as an Action Officer in Operations Division, Plans, Policies and Operations, Headquarters Marine Corps. He holds a master’s degree in security policy studies from the George Washington University’s Elliot School of International Affairs. These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the official views of any U.S. government department or agency.

References

1. “Summary of the National Defense Strategy of the United States.” U.S. Department of Defense. 2018. Pg 2

2. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2021 Annual Report to Congress.” United States Department of Defense. November 2021. Pg 123

3. Wood, Piers and Charles Ferguson. “How China Might Invade Taiwan.” Naval War College Review; Volume 54. November 2001.

4. Clay, Marcus, Dennis Blasko, and Roderick Lee. “People Win Wars: A 2022 Reality check on PLA Enlisted Force and Related Matters. War on the Rocks. 12 August 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/08/people-win-wars-a-2022-reality-check-on-pla-enlisted-force-and-related-matters/

5. Culver, John. “How We Would Know When China Is Preparing to Invade Taiwan.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 3 October 2022. https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/10/03/how-we-would-know-when-china-is-preparing-to-invade-taiwan-pub-88053

6. Harris, Shane, Karen DeYoung, and Isabelle Khurshudyan. “The Post Examined the Lead-Up to The Ukraine War. Here’s What We Learned.” The Washington Post. 16 August 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/08/16/ukraine-road-to-war-takeaways/

7. Easton, Ian. “The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia.” CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 3 October 2017. Ch 4

8. Wuthnow, Joel, Derek Grossman, Philip Saunders, Andrew Scobell, and Andrew Yang. “Crossing the Strait: China’s Military Prepares for War with Taiwan.” National Defense University. Washington, DC, 2022. Pg 118

9. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg 121-122

10. Easton. “The Chinese Invasion Threat.” Ch 4

11. Ibid.

12. “In their Own Worlds: Science of Military Strategy 2020.” China Aerospace Studies Institute. Montgomery, AL. January 2022. Pg 153.

13. 1945. “Taiwan has big Plans for its Missiles if China were to Invade.” Sandboxx. 4 August 2022. https://www.sandboxx.us/blog/taiwan-has-big-plans-for-its-missiles-if-china-were-to-invade/

14. Press Release. “Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office In The United States (Tecro) – Rgm-84l-4 Harpoon Surface Launched Block Ii Missiles.” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, United States Department of Defense. 26 October 2020. https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/taipei-economic-and-cultural-representative-office-united-states-17

15. Anderson, Nicholas. “Session 6: Introduction to Maritime Operations.” The Analysis of Military Operations. Fall 2022. Slide 55

16. Shlapak, David, David Orletsky, Toy Reid, Murray Tanner, and Barry Wilson. “A Question of Balance: Political Context and Military Aspects of the China-Taiwan Dispute.” The RAND Corporation. 2009. Pg 51.

17. “2021 Annual Report to Congress.” Pg 163

18. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg. 330

19. Press, Daryl. “The Myth of Air Power in the Persian Gulf War and the Future of Warfare.” International Security Volume 26. Pg 31.

20. Heginbotham, Eric. “The US-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996 – 2017. The RAND Corporation. 2015, Pg 128

21. Ibid. Pg 128

22. “2021 Annual Report to Congress.” Pg 161

23. Ibid.

24. “Taiwan Navy Launches Third and Fourth Indigenous Mine-Laying Ships.” Naval Recognition; Naval News December 2021. 17 December 2021. https://navyrecognition.com/index.php/naval-news/naval-news-archive/2021/december/11132-taiwan-navy-launches-third-and-fourth-indigenous-mine-laying-ship.html

25. “Hämeenmaa Class.” Naval Technology. 14 September 2010. https://www.naval-technology.com/projects/hameenmaaclassminela/

26. “The Military Balance. Chapter Six: Asia. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group. 14 February 2022. Pg 93

27. Talmadge, Caitlin. “Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz.” International Security, Vol 33. Summer 2008. Pg 89 – 96

28. Ibid. Pg 259

29. Talmadge. “Closing Time.” Pg 89 – 96

30. “Taiwan’s Best Landing Sites Are Well Defended.” Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/toaster/v2/charts/2a1fb12a801548c0971a9eb0c0e43f52.html?brand=politics&webTheme=light&web=true&hideTitles=true

31. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg. 144

32. Office of the Secretary of Defense. “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022 Annual Report to Congress.” United States Department of Defense. November 2022. Pg 165

33.“Republic of China Army.” GlobalSecurity.org. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/taiwan/army.htm

34. Yeo, Mike. “Taiwan Unveils Army Restructure Aimed at Decentralizing Military.” Defense News. 17 May 2021. https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2021/05/17/taiwan-unveils-army-restructure-aimed-at-decentralizing-military/

35. Office of the Secretary of Defense. “Military and Security Developments Involving the PRC.”

36. Huang, Paul. “Taiwan’s Military is a Hollow Shell.” Foreign Policy. 15 February 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/15/china-threat-invasion-conscription-taiwans-military-is-a-hollow-shell/

37. Huizhhong, Wu. “Army Reserve Worry Taiwan as China Looms.” Taipei Times. 12 September 2022. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2022/09/12/2003785178

38. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg. 224 – 230

39. Ibid. Pg. 224 – 230

40. Shlapak, Orletsky, Reid, Tanner, and Barry Wilson. “A Question of Balance.” Pg 116

41. Posen, Barry. “Measuring the European Conventional Balance: Coping with Complexity in Threat Assessment.” International Security, Volume 9. 1984.

42. “MAGTF Planner’s Reference Manual.” MAGTF Staff Training Program Division (MSTPD). Training and Education Command; United States Marine Corps. 11 January 2017.

43. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg. 232

44. Ibid. Pg. 231

45. Ibid.

46. Shugart, Thomas. “Mind the Gap, Part 2: The Crossing-Strait Potential of China’s Civilian Shipping has Grown. War on the Rocks. 12 October 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/10/mind-the-gap-part-2-the-cross-strait-potential-of-chinas-civilian-shipping-has-grown/

47. Wuthnow, Grossman, Saunders, Scobell, and Yang. “Crossing the Strait.” Pg. 146

48. Ibid.

49. Work, Robert. “A Joint Warfighting Concept for Systems Warfare.” Centers for New American Security. 17 December 2020. https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/a-joint-warfighting-concept-for-systems-warfare

50. “National Exercise Program Base Plan.” Federal Emergency Management Agency. Washington, DC. 22 Oct 2018.

51.“NEP Overview Flyer.” Federal Emergency Management Agency. Washington, DC.

52. Quinn, Jimmy. “What a Taiwan War Game Taught Congress.” National Review. 20 April 2023. https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/what-a-taiwan-war-game-taught-congress/.

Featured Image: Marines assigned to a brigade of the PLA Navy Marine Corps move forward for assault after disembarking from their amphibious armored vehicle during a beach raid training exercise in the west of south China’s Guangdong Province on August 17, 2019. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Yan Jialuo and Yao Guanchen)