By Dale A. Jenkins, with contributions from Dr. Steve Wills

The Battle of Midway in June 1942 is best known for the brave actions of U.S. Navy carrier pilots who, despite heavy losses and uncoordinated action, were able to find and destroy four Japanese carriers, hundreds of Japanese naval aircraft, and hundreds of irreplaceable Japanese aviators and deck crews. What is not often remembered is that the defense of Midway was a joint effort with Marine Corps and Army aircraft also playing a brave role in the defense of the island against Japanese attack. Today, the U.S. military almost always fights in a joint context, and the Battle of Midway, especially in the key decision of the Japanese strike commander to rearm his reserve force for a second attack a Midway, highlight that even a small joint contribution can force an opponent to make fateful decisions. In this case, joint action contributed to a decision that cost the Imperial Japanese Navy victory and likely sealed the fate of its four-carrier task force and the lives of thousands of Japanese sailors.

A Joint but Disorganized American Team

By May 27, 1942, a week prior to the Battle of Midway, the code breakers at Pearl Harbor were able to advise Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester Nimitz that the Japanese Striking Force, which included at least four aircraft carriers, would launch an air attack at first light on June 4th against the defenses on Midway Island to prepare for an amphibious landing on the island. Nimitz reinforced Midway with every plane he could mobilize to defend the island: old Buffalo fighters and a few new Wildcats, Avenger torpedo planes, B-26 and B-17 bombers, Marine Dauntless dive bombers, Vindicators, and amphibious PBY Catalina patrol aircraft. Among these aircraft were a number of Marine Corps and Army aircraft. Nimitz planned to have three Pacific Fleet aircraft carriers, Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown in a flanking position northeast of the projected southeast Japanese track aimed directly at Midway, and then to coordinate with the land-based aircraft to concentrate his aircraft over the Striking Force for a simultaneous attack on the Japanese forces.

Poorly Coordinated Air Battle

While Army and Marine Corps aircraft did not make up the majority of the combat aircraft, they had the vital role of supporting Navy patrol aircraft by expanding the search around Midway Island and providing more early warning. Without the Army B-17 bombers performing maritime search, fewer Navy aircraft would have been less to patrol around the carrier task force. Although Navy patrol aircraft ultimately detected the Japanese occupation and striking forces, the additional patrol space provided by Army aircraft helped ensure the detection and warning to Midway before the attack.

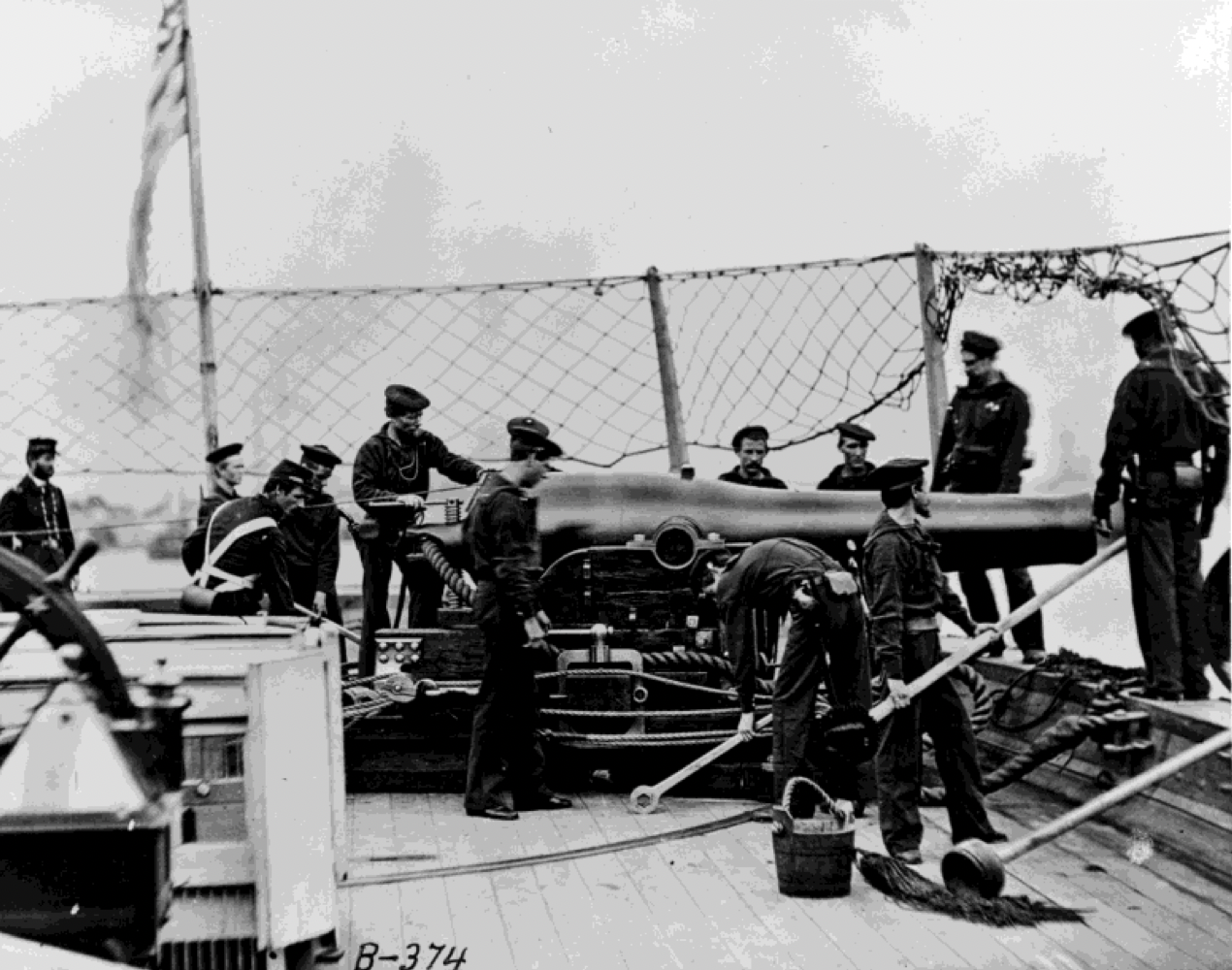

At 0430 on June 4, the Japanese carriers launched 108 planes, half of their total force, to attack the Pacific Fleet shore defenses on Midway Island. The remaining planes constituted a reserve force: attack planes armed with anti-ship torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs, and a large complement of Zero fighters. At 0603, a U.S. PBY patrol aircraft from Midway located the Japanese carrier fleet. Strike aircraft from Midway flew to intercept the Japanese carriers and land-based Buffalo and Wildcat fighters rose to defend the island. Marine Corps gunners on Midway fired antiaircraft guns at the attacking Japanese aircraft. The military facilities on Midway were heavily damaged in the attack with hangers and barracks destroyed. Casualties among the Midway aircraft defending Midway were equally heavy. Of the 26 Marine Corps F2F Buffalo and F3F Wildcat aircraft that opposed the Japanese strike on Midway, fifteen were lost in combat. At the end of the battle only two air defense fighters were still operational to defend the island.

The joint attackers flying against the Japanese carriers fared little better than the joint air defense fighters. Six Avenger torpedo planes and four B-26s were the first to reach the Japanese carriers just after 0700 and were opposed by thirty Japanese Zeros. Five of the six Avenger torpedo planes were shot down trying to attack a Japanese carrier. Two B-26 aircraft targeted another carrier, and one was shot down, and two escaped after their ineffective torpedo drops. The fourth B-26 was on fire, and the pilot may have attempted a suicide crash into the bridge of Japanese flagship Akagi, but he narrowly missed and ended up in the ocean. During this encounter, the carriers were forced to maneuver, and although the attacks from the Midway planes failed to score any hits, they caused alarm and confusion in the Japanese command. Aircraft from the Pacific Fleet carriers, however, failed to appear because the carriers at 0600 were over sixty miles away from their expected position, were beyond their operating range and did not launch. As a result, Admiral Nimitz’s plan for a concentrated attack failed. Joint coordination of fires is an absolute necessity in operations and the resulting failure of the Midway-based joint air attack to inflict damage is a good example of what happens when coordination is not present.

Operational and Tactical Effects of Indecision

The operational effect on the Battle of Midway from their disjointed Marine Corps and Army aircraft, and later those of U.S. carrier torpedo squadrons, however, was significant. Japanese Striking Force commander Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo received a message earlier from the commander of the Midway attack force recommending another attack on Midway but was slow in deciding how to respond. Because of the desperate attacks from Midway, and his personal narrow escape on the Akagi bridge, Nagumo decided the reserve force needed to launch a second attack on Midway. At 0715 he ordered a change in the ordnance of the reserve planes from torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs to the high explosive impact bombs used on land targets. At 0728, a Japanese scout plane sent a message – ten enemy ships sighted; ship types not disclosed.

Now Nagumo was presented with a dilemma, he had two different targets – the facilities on Midway Island and the now-spotted ships. He decided to let his returning Midway strike force land first and then launch his reserve force armed with torpedoes to attack American ships. This required changing the ordnance loaded on his reserve aircraft back to torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs from the weapons loaded to attack Midway a second time. This difficult and time-consuming operation would cause a substantial delay in getting the aircraft airborne.

The disruption of the Japanese air planning cycle by Marine Corps and Army aircraft yielded key tactical results as well. The Japanese planes that had attacked Midway returned as planned, beginning at 0830. They all landed by 0917, but an attack of all four refueled and rearmed air groups against the Pacific Fleet carriers would not be ready to launch until about 1045, at the earliest. Authors Jonathan Tully and Anthony Parshall noted, “the ceaseless American air attacks had destroyed any reasonable possibility of “spotting the decks” (preparing for strike aircraft recovery before Tomonaga’s (the commander of the Japanese Midway bombing attack force) return because of the constant launch and recovery of combat air patrol (CAP) fighters,” needed to intercept the attacking Army and Marine aircraft from Midway. This Japanese loss of tempo in Japanese carrier operations due to these attacks would prove fatal of the Japanese force.

Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance, in command of carriers Enterprise and Hornet, had closed the range and dispatched full air groups from both carriers at about 0710. At 1025, Dauntless dive bombers from Enterprise, running extremely low on fuel, found and destroyed two Japanese carriers. At the same time Yorktown dive bombers destroyed a third carrier. Several hours later Enterprise dive bombers destroyed the fourth carrier, but not before its attack on Yorktown led to the loss of that ship. At the end of the day, Pacific Fleet carrier pilots had scored a major victory that marked a turning point in the Pacific War.

The attacks of the Midway-based aircraft had not scored any damage on the Japanese carriers or their escorts, but they contributed to the overall victory by keeping both the Japanese aircraft and ships engaged and unable to re-arm effectively for another Midway attack, or a strike on the American carriers. The delays in preparing this strike, and some luck left Japanese aircraft re-arming and refueling below decks when U.S. carrier-based dive bombers attacked, and they hits they scored on those planes caused conflagrations on the Japanese flattops that could not be extinguished.

Joint Lessons

The attacks by the Midway-based joint strike failed in their tactical mission but yielded later successful tactical and operational results. The Navy recognized the value of the B-17 in a scouting role to the point that Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King ordered a number of Army aircraft for naval service. The Army believed that the B-17’s from Midway had inflicted damage on the Japanese fleet, but the failed horizontal bombing attacks by the big Army bombers convinced the Japanese to ignore the Army planes in the future. Failures in hitting Japanese ships later in the Solomons campaign caused the Army to re-assess the B-17’s ability to attack ships. The Army later discovered that “skip bombing,” a process developed with the Australians was a more effective means through which Army aircraft could attack ships.

The joint aspect of Midway’s defense continued as Army Air Force aircraft provided defense of the island well into 1943 due to shortages of Navy and Marine Corps aircraft committed elsewhere in the Pacific War. The Marine Corps 6th Defense battalion remained in garrison on Midway until the end of the war, and the idea of Marine Air/Ground forces engaged in sea control warfare is returning to the Marine Corps in the form of Marine Littoral Regiments in Force Design 2030. The value in understanding the Battle of Midway from a joint perspective is that even the smallest amount of joint action at a crucial phase can fundamentally improve the odds of joint force success.

Dale A. Jenkins is the author of Diplomats & Admirals, 402 pages, Aubrey Publishing Co., New York, Dec. 2022.

Dr. Steve Wills is a navalist for the Center for Maritime Strategy.

Featured Image: Torpedo Squadron Six (VT-6) TBD-1 aircraft are prepared for launching on USS Enterprise (CV-6) at about 0730-0740 hrs, June 4, 1942. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives)