By Matthew Merighi

Join us for the latest episode of Sea Control for a conversation with Dr. Alison Russell of Merrimack College about navies and their relationship with cyber. It’s about the distinct layers of cybersecurity, how navies use them to enhance their capabilities, and the challenges in securing and maintaining that domain.

Download Sea Control 143 – Cyber Threats to Navies with Alison Russell

This interview was conducted by the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University. A transcript of the interview between Alison Russell (AR) and Roger Hilton (RH) is below. The transcript has been edited for clarity. Special thanks to Associate Producer Cris Lee for producing this episode.

RH: Hello and Moin Moin, Center for International Maritime Security listeners. I am Roger Hilton, a nonresident academic fellow at the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University, welcoming you back for another edition of the Sea Control series podcast. Did any listeners read the news on twitter, message your friend on Facebook, or even do some mobile banking? Are you streaming this podcast for your enjoyment? If you did any of the above, like myself, you are dependent on the internet. So logically, based on this fact, it should come as no surprise that contemporary navies are as well. Naval technological capabilities and strategies have exponentially evolved from the nascent beginnings. Steam ships have been replaced by nuclear powered carriers while cannons have been substituted for intercontinental ballistic missiles. No doubt the power of modern navies is awesome, and as a result, their dependency and reliance on the cyber realm must not be overlooked.

Consequently, does this interconnectedness between hardware and software in fact leave 21st century navies more exposed to attacks from invisible torpedoes than actual physical ones? Here to help us navigate the minefield of the cyber threats facing both naval strategy and security is Dr. Allison Russell, she’s a professor of political science and international relations at Merrimack College in Massachusetts and a nonresident researcher at the Center for Naval Analyses. In addition, she’s the author of two books, Cyber Blockade and more recently, Strategic A2AD in Cyberspace. Dr. Russell, thanks for coming aboard today.

AR: It is great to be speaking with you Roger. Thank you for having me in your program today.

RH: Well, let’s get right into it. There’s no doubt that cyberspace and threats associated with it are hot topics today. While much of the news coverage on cyber threats is focused on hackers spreading disinformation, or even potentially gaining access to critical infrastructure, can you provide an initial overview of the role cyber plays in the contemporary maritime environment and as well as some of the menaces targeting the Navy?

AR: I would be glad to. As you pointed out, much of the attention on cyber threats focuses on hackers, data thefts, cyber espionage, and information or influence campaigns. And those are important. But these really are not the biggest threats in the maritime environment. The threats naval forces face in a maritime environment vary depending upon the part of cyberspace we’re talking about.

See, there are four levels in cyberspace: the physical, the logic, the information, and the user layers. The physical layer is the physical infrastructure, the hardware that underpins the global grid that is the basis of cyberspace. Although we tend to think of the internet and cyberspace as wireless or in the cloud, it is very much reliant upon physical infrastructure at its most basic level. Fiber optic cables including undersea cables, and satellites comprise some of the more prominent features of the physical layers of cyberspace.

The second layer is the logic layer. This is the central nervous system of cyberspace. This is where the decision-making and routing occurs to send and receive messages to retrieve files, really to do anything in cyberspace. The request must be processed through the logic layer. The key element of the logic layer are things such as DNS, the Domain Name Servers, and internet protocols.

The third level is the information level. This is what we see when we go on the internet: Websites, chats, emails, photos, documents, apps. All of that is the information posted at this level. But it is reliant on the previous two levels in order to function.

Lastly, the fourth level is the user level: the humans who are using the devices and are interacting with cyberspace. They matter because cyberspace is a man-made entity and its topography can be changed by people. Cyberspace is critical to modern naval strategy and security because it underpins the essential communications networks and capabilities of naval forces. And adversaries will seek to destroy or degrade those capabilities in the event of a conflict. Cyberspace enables robust command and control, battlespace awareness, intelligence gathering, and precision targeting, which are at the core of mission success. These days navies must defend and maintain their freedom to operate within cyberspace in order to be effective forces at sea.

RH: Thanks for the brief outline. As I mentioned earlier the identity of the navy has changed greatly since its original inception into conflict theaters. Accordingly, the advent of cyberspace has added an entirely different dynamic to the field. And you mention some of them as well. Consequently, what are some of the new responsibilities that have arrived with the integration of cyber to navies? And in general, what is the role the navy plays within a larger national security architecture?

AR: The cyber capabilities are really integrated at all levels at the naval mission. So, the core capabilities navies seek to provide are the blue-water capabilities of forward presence, deterrence, control, sea control, and power projection, as well as maritime security and humanitarian assistance or disaster response. All of these core capabilities are supported and enhanced by cyber capabilities. Thus, the full spectrum of naval operations and the corresponding naval strategy involve cyber capabilities today.

For more technologically advanced navies, these cyber capabilities are so integrated into weapon systems and platforms, that they’ve become essential to full spectrum warfighting operations. For the less technologically advanced navies, cyber capabilities can still play an important role in augmenting other capabilities by providing command and control and acting as a force multiplier in certain situations. In addition to their blue water role, naval forces are responsible for providing cyber capabilities to support combatant commanders’ objectives in defense of national information networks and for fleet deployment. They are force providers to joint and interagency operations. They are supporters of the national mission and blue-water warriors all at the same time. As a result, they must have a holistic, full spectrum understanding of the role cyberspace plays from tactics to operations to grand strategy.

RH: That was a great encompassing of it. As you can see it comes full circle when you compare conflict theatres to human assistance missions which is great you mentioned. At the same time Dr. Russell, you cite out naval strategies are in a period of transition at the moment. Could you elaborate on these implications with regard to how cyberspace is impacting the current formation of national naval strategies?

AR: Yes, naval strategies are in a period of transition with regards to cyberspace. Most navies acknowledge the importance of cyberspace as a critical enabler, but there’s emerging recognition that cyberspace is also much more than that. Ultimately, cyberspace is a game changer for naval forces and security forces in general. All phases of conflict now have a cyber dimension. From phase zero planning to phase five stabilization and reconstruction, cyberspace affects all levels of war, from strategic to the operational to the tactical. All types of conflict are affected by cyberspace including conflicts in the other four domains. For naval forces in particular, cyberspace enables new kinds of fires: Cyber-fires. It improves situational awareness and enhances command and control.

It has also opened the door to new threats. Anti-access and area denial operations, improved targeting capabilities by adversaries, and presenting more targets for attack in the form of cyber-attacks. As naval forces adopt next technologies to leverage the unique capabilities of cyberspace, reliable access to cyberspace is a necessity. Assuring access to cyberspace and confident C2 for deployed forces regardless of the threat environment is a top priority for the U.S. Navy as well as for many others.

RH: There’s no doubt based on your texts and some of the other content out there that reliable access seems to be driving naval strategy and security, especially among the technically advanced navies. So thank you for mentioning that to the listeners.

We spoke about technologically advanced navies and less technologically advanced navies. To demonstrate some of the diversity in strategy, can you provide a quick comparison about how some of the national strategies have integrated cyberspace in their doctrine?

AR: Yes, I think a comparison of the U.S. and Russia helps to illustrates this.

RH: You couldn’t have picked two better countries to compare at the moment, so thank you for that selection, Dr. Russell.

AR: (Laughs) Well, there’s a lot of interesting things happening there. The current U.S. maritime strategy, the 2015 Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, has incorporated cyberspace and cyber power into that strategy in a very robust way. The strategy talks exclusively about all domain access and cross-domain synergy. By which it means, synchronizing battlespace awareness with all the layers and sensors and intelligence within that, and synchronizing that with the short access to networks. Offensive and defensive cyber operations, electromagnetic maneuver warfare, and integrated kinetic and non-kinetic fires. All of this is apparent in U.S. maritime strategy as essential elements in supporting the naval mission. And it’s all spelled out.

In contrast, there is very little information that is publicly available about how cyberspace effects the Russian maritime strategy. At last check, Russian maritime strategy does not directly address cyberspace and cyber security as a maritime or naval responsibility. But it does recognize the importance of what it calls information support of maritime activities for the maintenance and development of global information systems, including systems for navigation, hydrographic, and other forms of security. Most of the publicly available Russian cyber strategy in general focuses on information operations and disinformation campaigns. Despite having advanced cyber-capabilities, there’s not much information available on how that is being integrated into the Russian naval strategy.

RH: You know, it’s very unfortunate that there was no release of any new information recently in St. Petersburg, they celebrated national Navy day with President Putin visiting. But I guess we’ll have to stay on the lookout for any new information.

Before we even go up into the highly integrated platforms of navies in cyber, you reference very acutely the Kremlin’s use of synchronized fires. Can you briefly elaborate on what this concept is and if we can expect to see a similar pattern in future conflict theaters?

AR: Yes, without a doubt I think we can expect to see a similar pattern in the future. For those who don’t know, during the Russia-Georgia War of 2008, Russian forces assaulted Georgia on land, in the air, and from the sea, while at the same time Georgia was subjected to destructive distributed denial of service or DDOS attacks on the websites of Georgian government offices, financial services, and in news agencies. So, this was a synchronized attack in multiple domains on Georgia from Russia simultaneously.

In the Russia-Ukraine conflict, similarly Ukraine suffered multiple cyber attacks in conjunction with that conflict, including cyber attacks targeting infrastructure. I think that these synchronized integrated fires will likely continue and eventually become the norm in conventional conflict unless some action is taken, diplomatically or otherwise, to limit the use of cyber fires or restrict the number of quote unquote “legitimate” cyber targets.

RH: Again, that’s Russia picking on countries that are less developed, but it would be interesting to see moving forward against another more developed or modern adversary if it would be as effective a concept. When assessing operational level warfare, as well as tactical level warfare, how does cyberspace enhance their application?

AR: Starting with the operational level, cyberspace operations can be categorized in three ways: Offensive action, defensive action, and network operations.

Offensive cyberspace operations are designed to project power through the application of force in or through cyberspace. They’re cyber attacks. Defensive cyberspace operations are intended to defend national or allied cyberspace systems or infrastructure. Network operations design, build, configure, secure, operate, and maintain information networks and the communications systems themselves to ensure the availability of data, the integrity of the system, and confidentiality. So those all work together on operational level.

So, to give an example, we already talked about how cyberspace enables assured command and control, integrated fires, battlespace awareness, intelligence, as well as protection and sustainment. It also enables naval maneuvers, with positioning, navigation, and timing support. For sea-based power projection, in a landscape that is very often devoid of signposts and landmarks, the ability to have precise navigational information and over-the-horizon situational awareness is particularly critical. Cyber and satellite-based global positioning and navigational systems provide this capability. Beyond the navy itself, commercial and academic institutions that provide support to the fleet or the military in the form of design, manufacturing, research, and other products and services, are also part of the broader environment for naval security.

So, naval security and warfighting advantage depends in part upon thwarting attacks on military or government sites, as well as securing sensitive information from cyber theft or cyber espionage. Sensitive information in the wrong hands can of course undermine the operational effectiveness of the fleet by improving targeting of naval forces by adversaries and increasing the adversary’s knowledge of how forces man, train, and equip for warfighting.

Moving to the tactical level, naval commanders must incorporate the use of cyber technologies into their battlefield tactics. In practical terms, this means that defensive and offensive cyber capabilities will be integrated alongside kinetic action. This is the integrated fires. Cyberspace can increase the effectiveness of traditional kinetic fires through improved intelligence and targeting. But it also presents new challenges for defensive operations to protect these systems from cyberattack as well as kinetic fires.

Cyberspace and cyber capabilities play a particularly important role in supporting network-centric weapon systems, such as the tactical Tomahawk missile, which the U.S. launched into Syria in April. Tactical Tomahawks receive in-flight targeting data from operational command centers. Similarly, carrier aviation maintenance programs rely on cyberspace to enable them to provide mission ready aircraft.

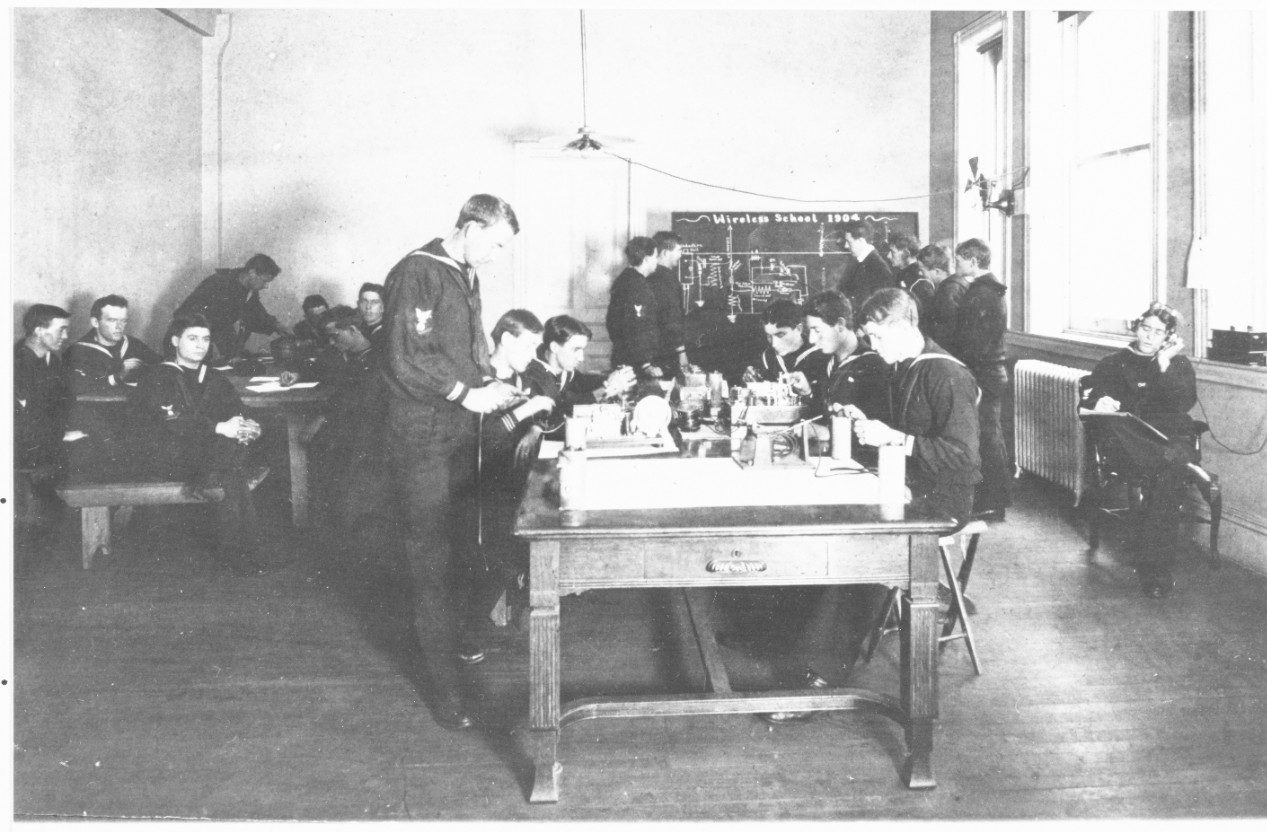

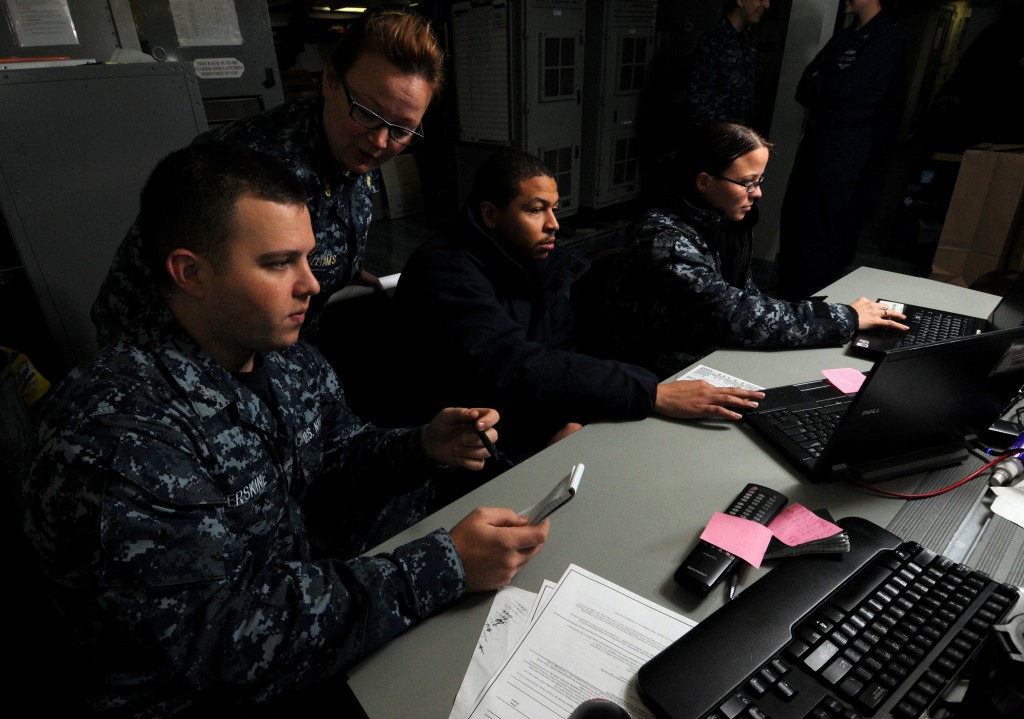

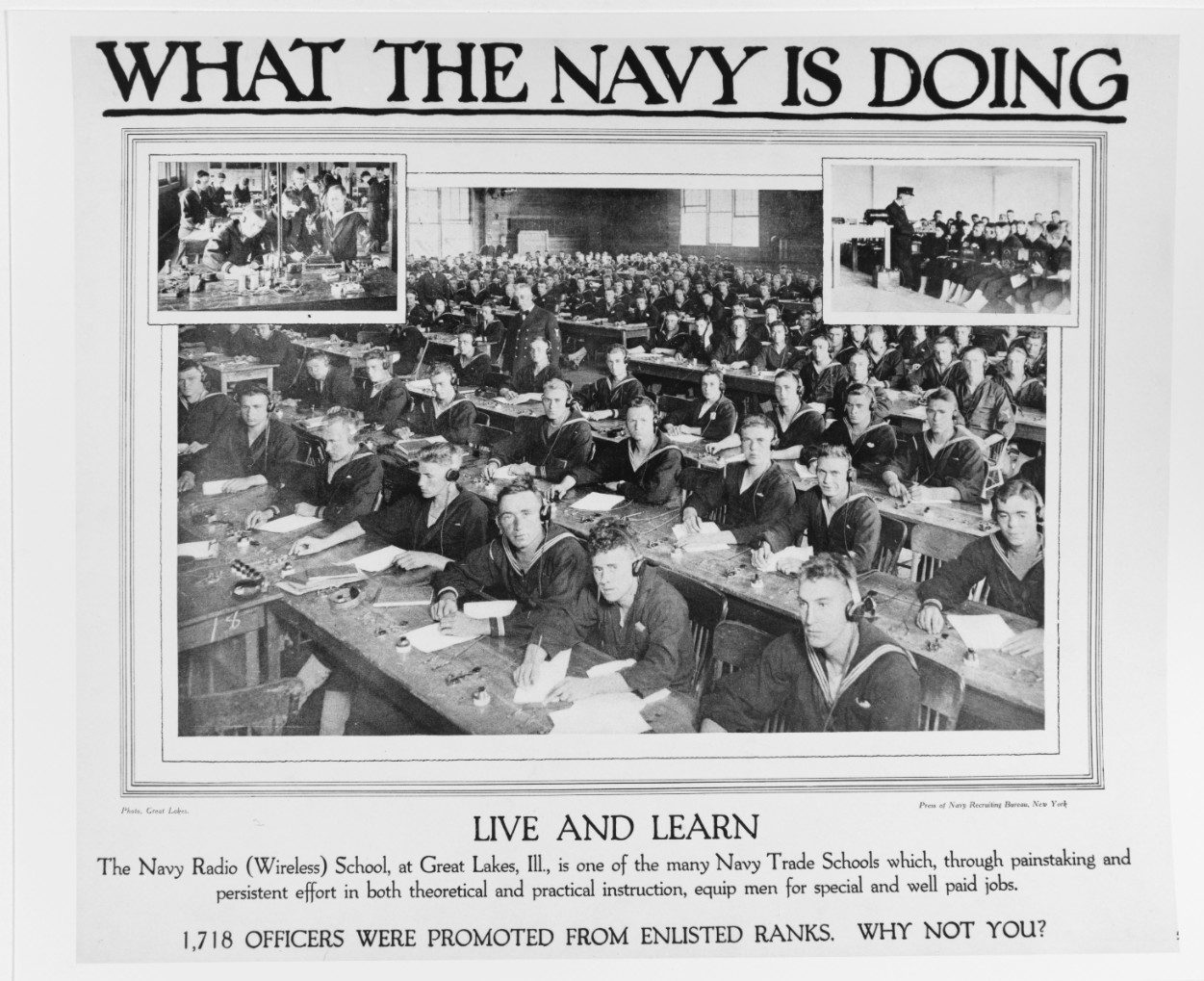

There are alternatives and workarounds to overcome system failures, but the point is that reliable access to cyberspace is critical to the successful employment of these systems. Naval security also depends upon the protection of access and critical information whether it is classified or not. For naval forces, this process of protecting critical information means educating and training sailors in good cyber hygiene habits and having cyber security integrated into the life cycles of systems.

RH: Moving on, we’ve discussed how naval strategies revolve around the four key layers. It is clear that the structure of cyberspace begins with the physical layer. Sometimes users forget how hardware like fiber optic cables and satellites are hidden from view in our daily use of cyberspace. It looks to be a frightening future as you provided a few examples that confirm how vulnerable these physical elements are to tampering.

An appropriate contextualization for the listeners of this threat was on display in a 2015 New York Times article that describes increased Russian submarine activity and how the construction of unmanned, undersea drones related to fiber optic cables is rattling the Pentagon. According to Rear Admiral Fredrick Roegge, commander of the Navy Submarine fleet Pacific (COMSUBPAC) he was quoted as saying, “I’m worried everyday about what the Russians could be doing.” What is your take on the threat to the physical layer and is this threat explicitly exaggerated? Or is it a feature that national security policy makers should be more concerned with?

AR: That’s a great question, I don’t believe that it’s exaggerated. The cables carrying global business for more than $10 trillion per day and 95 percent of daily communications. They are very important to our global economic and political structure.

Back in the 70s before there was a system as robust and widespread as it is today, the U.S. was willing to take great risks to tap into the cables in Soviet waters to gain intelligence. Now these cables carry much more information and have much more value in the present context. The Russians are seeking to identify and potentially exploit infrastructure weaknesses of the US and the West. So, I think it is absolutely worth being concerned about.

RH: Can you comment a little bit on what would happen in the event of tampering and what the process of repair might look like moving forward?

AR: Well, it’s a little hard to speculate on exactly what would happen, but somethings that could happen is, cables could be severed, they could be cut, which would cause a slowdown in the system, and it would be difficult to repair them, particularly because these cables lie along the ocean bed, the floor of the ocean. And so, there are a certain number of ships in the world that can go to these places and fix the cables and that can be a process that is expensive and is time consuming. That’s just one scenario where the cables are cut.

Another scenario is that they can be potentially tapped into somehow. That is, of course, what the U.S. did to the Soviet Union in Operation Ivy Bells in the 1970s, and that was used for espionage purposes. So, something along those lines could be done with these cables with information being stolen or simply recorded and copied, but then passed along so that nobody knows that someone else was listening in. So, there are a variety of different things and they would require different responses, but some of them would be difficult to detect and to identify that there was a problem, while others like a cut in the cable would be immediately apparent.

RH: In terms of the logic layer, do you think it’s conceivable that a Stuxnet-like attack could seriously damage naval operations? It is worth noting to our audience that even in the case of air-gapped networks, which is what Iran was using, infections from viruses are still possible.

AR: I think it is entirely possible that a cyber-attack could manipulate the logic layer of cyberspace in a number of ways which could cause it to malfunction or shut down completely in order to inhibit the flow of data, which could directly affect naval operations. You make a very good point that even air-gap networks are still at risk. The Stuxnet attack happened 10 years ago, but it successfully targeted highly sensitive protected air-gap systems. And the technology and cyberweapons have advanced quite a lot in the decade since then.

RH: It seems like a bit of an antiquated question, but in the event, that a Stuxnet attack hit a naval operation, what would the response of the Navy be? I mean, do they still know how to use compasses and work like they did back in the day?

AR: (Laughs) This is a good question. But there are workarounds. There are capabilities that are redundant that have resiliency built in. Things would not function perfectly, but most things would still continue to function, so they would still be able to get to where they were going, but they wouldn’t be as effective as they’re intended to be. And so, it would be problematic. Absolutely.

RH: Just as an example for listeners though, but again theoretically, if there was a Stuxnet attack on an operation, it could kill the ability of network-centric weapons to function, correct?

AR: It has that potential, or could cause them to malfunction. So, an object could appear to go on course go off course, or not be able to function entirely or, if it’s ordnance, explode too early, something along those lines.

It can cause a variety of effects, depending on exactly what type of attack it is and what it’s designed to do. Because these attacks – we say attacks in cyberspace happen very quickly because they do in cyberspace – but they also typically take a very long time to develop.

So, that’s another thing where we can develop the cyberweapons and keep them until you’re ready to use them, they do take a while to actually develop. But once you deploy them they happen almost immediately.

RH: A lot of those symptoms you just mentioned earlier about, sort of, missiles veering off course or exploding too early, that’s also a good way to look at the early stages of the North Korean missile program, which unfortunately has evolved to a dangerous point right now. But that’s also maybe a good example if you would agree about the various difficulties that come with a Stuxnet like attack on any sort of cyber infrastructure.

AR: I think that’s an excellent sample.

RH: Drives people crazy in Pyongyang. We have an established the crucial role of cyber for naval strategies, and touched on the composition and structure. Against this backdrop, what are the main opportunities for naval forces and policy makers moving forward with cyber?

AR: Well, there are many potential opportunities but there are three that I think are the most important and exciting.

The first is improved battlespace awareness. Cyber capabilities allow naval forces to have a better understanding of the environment in which they are operating and that is very very good for them.

The second is that cyberspace presents new opportunities for modelling and simulation to help naval forces prepare and train for warfighting.

And then third, as a new domain, cyberspace presents opportunities for cooperation with partner nations for developing, maintaining, and protecting a domain to ensure things like reliable access for allies and partners. And limiting the adversary’s maneuverability within the domain.

So, the domain is essentially a blank slate for cooperation within the international community. That provides some really exciting and interesting opportunities.

RH: Despite these improvements in the maritime domain, it is safe to say that you still remain skeptical of the numerous challenges that threaten naval security. Can you identify and describe some of the major threats? To either advanced technological navies or less advanced navies.

AR: Yes, and there are many challenges, but again I’ll pick the top three that I consider to be the most dangerous or the most important:

First, anti-access and area denial operations in cyberspace are the most significant challenge to the basic goals of naval forces: To retain freedom of maneuvering in cyberspace and deny freedom of action to the adversaries. Cyberspace is essential to naval operations so therefore; the protection of cyberspace is also essential. It doesn’t matter how new or fancy your ships are, if they don’t have the capabilities you need because you can’t access cyberspace. So, I think the most important challenge is, maintaining access to the domain.

The second is significant challenge for naval forces is that offense has the advantage. Threats in cyberspace develop faster than forces can protect against in many cases. The domain is constantly evolving, and innovation is happening so quickly that creating new systems, platforms, and tools occurs at a rapid pace. With the creation of new applications comes the opportunity for new vulnerabilities within the systems. Adversaries are constantly seeking new ways of attack or penetration of networks.

While defensive cyber operations have to work very hard to keep up with the constant onslaught of attacks, there are things like advanced persistent threats, APTs, that are these stealthy persistent attacks on a targeted computer system in order to continuously monitor and extract data. These are particularly problematic because they are so difficult to detect and could render significant damage. We just saw recently that a very prominent cyber security firm was actually targeted with the use APTs, which is very worrying given that they are a prominent cyber security firm. And in addition, the speed at which some cyber attacks can take place, the relatively low barriers on entry to cyberspace, and the potentially big impact of an attack provides a lot of incentive for attackers to keep trying. So, it’s difficult for defensive operations to keep up with them and innovate to protect against future attacks.

RH: I have to be honest Dr. Russell, based on our discussion and the litany of challenges, I’m more inclined to believe that navies will remain exposed to invisible torpedoes more so than physical ones. But hopefully the offensive actions and the various layers will become more resilient in defending and fighting them off. Undoubtedly, it has been an eye-opening podcast that has served to expand our collective assessment on the role of cyberspace and the implications for both naval strategy and security. As we sail off on another sea control series podcast Dr. Russell, do you have any operational takeaways for the listeners or the issues they should pay special attention to?

AR: Well, the rise of cyber capabilities of allies and adversaries such as precision targeting and long-range attacks on systems mean that navies will be simultaneously more connected and more vulnerable at sea than ever before. The modern Navy has so many capabilities that rely on cyberspace that it must not take access to cyberspace for granted. As our ships grow smarter and we invest more and more in the high-end capabilities that allow this unprecedented array of actions, let us not forget to simultaneously ensure that the cyber-connected systems are protected so that our new technology can be used effectively when it’s called upon.

Sun Tzu observed that it is best to win a war without fighting. If modern navies did not have access to cyberspace, it would be very difficult for them to fight. The goal of the navies in the future will be to retain freedom of maneuver and deny freedom of action to adversaries at sea. As well as in cyberspace.

RH: Dr. Russell, thank you again for taking the time to enlighten us on such a relevant and complicated issue.

If our listeners want to follow up in more detail on cyberspace and maritime strategy, or gain a better outlook on the general maritime domain, The Routledge Handbook of Naval Strategy and Security, edited by Sebastian Bruns and Joachim Krause, published in 2016 is an indispensable resource to have. Please check www.kielseapowerseries.com for more info on the book and other podcasts derived from the book.

With no shortage of maritime issues within the greater geopolitical landscape, I promise I will be back to keep CIMSEC listeners well-informed. From the Institute for Security Policy at Kiel University and its adjunct, the Center for Maritime Strategy and Security, I’m Roger Hilton saying farewell and auf wiedersehen.

Dr. Alison Russell is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Studies at Merrimack College. The author of Cyber Blockades (Georgetown University Press, 2014), she worked for six years as a security analyst at the Center for Naval Analyses where she specialized in naval strategic planning. She holds a Ph.D. from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, an M.A. in International Relations from American University in Washington, D.C., and a B.A. in Political Science and French Literature from Boston College.

Roger Hilton is a nonresident academic fellow for the Institute for Security Policy at the University of Kiel.

Matthew Merighi is the Senior Producer for Sea Control.