Read Part One on the Battle of Locust Point. Read Part Two on the Nanxun Jiao Crisis. Read Part Three on Operation Eminent Shield.

By David R. Strachan

TOP SECRET/NOFORN

The following classified interview is being conducted per the joint NHHC/USNI Oral History Project on Autonomous Warfare.

Admiral Jeremy B. Lacy, USN (Ret.)

December 4, 2033

Annapolis, Maryland

Interviewer: Lt. Cmdr. Hailey J. Dowd, USN

Good morning.

We are joined again today by Admiral Jeremy B. Lacy, widely considered the father of autonomous undersea conflict, or what has come to be known as micronaval warfare. Admiral Lacy spearheaded the Atom-class microsubmarine program, eventually going on to establish Strikepod Group 1 (COMPODGRU 1), and serving as Commander, Strikepod Forces, Atlantic (COMPODLANT), and Commander, Strikepod Command (PODCOM). He is currently the Corbin A. McNeill Endowed Chair in Naval Engineering at the U.S. Naval Academy.

This is the fourth installment of a planned eight-part classified oral history focusing on Admiral Lacy’s distinguished naval career and his profound impact on modern naval warfare. In Part I we learned about the genesis of the Atom-class microsubmarine and its operational construct, the Strikepod, and the series of events leading up to the first combat engagement of the micronaval era, the Battle of Locust Point. In Part II, we learned of how continued Russian micronaval advances led to the development of AUDENs, Autonomous Undersea Denial Networks. We also learned of CYAN, a walk-in CIA agent who revealed Chinese penetration of the AUDEN program, and the resulting emplacement of numerous AUDEN-like Shāyú microsubmarine turrets throughout the South China Sea. In Part III, we learned of Operation Eminent Shield, an unmanned distributed maritime operation where Strikepods and squadrons of Esquire-class unmanned surface vehicles squared off against China’s maritime militia in the South China Sea.

Today we turn to the Persian Gulf, and the employment of Strikepods and Esquires in countering the IRGCN during Operation Indigo Spear, the U.S. response to the so-called Second Tanker War, wherein Iran, lashing out after years of crippling sanctions and perceived bullying by the West, utilized an indigenous, weaponized UUV to wreak havoc on regional stability and the global economy.

We joined Admiral Lacy again at his home in Annapolis, Maryland.

Let’s begin today with Operation Indigo Cloak, the deployment of unmanned maritime systems to the Persian Gulf. Can you tell us how it came about, and what role PODCOM played?

Beginning in mid 2019, Iran engaged in an increasingly belligerent campaign of economic warfare against the United States and the West, lashing out against crushing sanctions, and the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, and looking to drive a wedge between Washington and those EU nations still abiding by the JCPOA. Needless to say, CENTCOM was keeping pretty busy, and once they got wind of what we’d achieved in the South China Sea with Eminent Shield, they were more than a little interested in what we could do for them. So, late in 2018, we shipped two 12-ship Strikepods and a squadron of Esquires down to NAS Bahrain to help monitor IRIN and IRGCN operations.

CENTCOM was also becoming concerned about Iranian UUVs and USVs, and specifically, the Navy’s ability to counter them.

Yes, the Iranians were taking an increasingly keen interest in unmanned maritime systems, so while our main objective was augmenting ISR and providing MCM if needed, we were also monitoring for any developments in that space, especially in the undersea domain where things seemed to be heating up.

What kind of intelligence were you receiving on Iranian UUVs?

For several years we’d been monitoring Iranian efforts to acquire a viable unmanned undersea capability. Front companies with ties to the IRIN [Islamic Republic of Iran Navy] and Iranian defense ministry were attempting to buy COTS inertial navigation systems, accelerometers, and various other components, and sometimes even entire vehicles. Tehran’s unmanned fetish was legendary. UAVs and USVs had served Iran and its proxies well, and so it was entirely reasonable to assume that they’d eventually pursue UUVs. But unlike air or surface drones, the technological barriers to entry for the undersea are pretty high, and appeared too great for Iran to overcome on its own. There’d been one attempt back in 2012, the Phoenix, that went nowhere, and became more of an instrument of propaganda. After that baby failed to thrive, their efforts appeared to stall, but in actuality they’d simply gone underground.

To a renewed relationship with North Korea?

One that would bear significant fruit, as it had with the Yono [Iranian Ghadir-class] boats.

Iran’s first UUV – the Qom?

Correct. The Qom was a rebranded version of the DPRK’s indigenous UUV, the Gwisin, or “Ghost.” The Gwisin was small, about a meter in length, and outfitted with a bunch of smuggled-in COTS technologies. It was kind of a cross between the Chung Sang Eo “Blue Shark” torpedo and a Riptide, with its intended role being ISR or possibly some ASW. But the Iranians literally wanted more bang for their buck. So from the outset the vision for the Qom wasn’t merely to keep an eye on us, but to harass us, or even hold us at risk.

Which the USS Higgins encountered in April of 2018?

We’d received some reports that the IRGCN had been experimenting with Qoms, trying to configure them as undersea armor-piercing EFPs [Explosively Formed Penetrators] and employing them in swarming attacks against surface and subsurface targets. Intelligence indicated that they were capable of around 20 knots, so even without a warhead, the kinetic energy alone might be enough to disable a UUV, SDV, or even a small surface combatant if properly aimed and concentrated.

So, yes, it was during TLAM ops against Syrian chemical weapons sites that we experienced what the IRGCN had managed to achieve. Tehran was not happy with a U.S. missile strike originating in the Gulf, so they decided to send us a message by slamming a swarm of a dozen or so Qoms into the Higgins hull. There was little damage, but it was a wakeup call – Iran’s unmanned ambitions now extended well into the undersea domain.

Were there indications at that time that Iran was developing an indigenous UUV?

There were rumors, and some circumstantial evidence that something else was in the works. It was a source of some pretty … lively debate within the IC. We were all in agreement that some kind of program did exist, but the nature of it, how advanced, or how far along it was – we really had no idea. We definitely had no evidence that the Iranians had an operational prototype, or that they intended to deploy it against ships in the Gulf. One thing we did know – while the Qom may have provided a boost to Iranian ISR, it wasn’t a particularly useful weapon against high-value targets, and that’s what the Iranians really wanted.

Then in early 2019, Cyber Command managed a successful penetration of the IRIN, and they uncovered some files related to a project called AZHDAR – “dragon” in Farsi. From what we could piece together, it appeared that at some point during Iran’s search for an offensive UUV capability engineers hit upon the idea of repurposing something already in the IRIN inventory – specifically, an e-Ghavasi SDV. Being a “human torpedo” type of SDV, the e-Ghavasi was well suited to the task, and it was already capable of carrying a 600 pound multi-influence mine, so all that was needed was sensor integration, a COTS navigation system, coms capability, some ballasting, and a central processor – something as simple as a Raspberry Pi.

But the really intriguing part? The schematics depicted the vehicle’s diving planes and bilge keel recessing into the hull, and the rear stabilizers folding like a Tomahawk’s.

Which suggested that the Azhdar was a sub-launched weapon?

Yes, but it wasn’t until Fujairah that our suspicions were confirmed.

Can you tell us about that day?

It was a warm, brilliant spring evening, and I was enjoying a “Mother’s Day Eve” cookout with my family. I got the call around 1715, and half an hour later I was at my desk at PODCOM, getting briefings every fifteen minutes. We had Strikepods strung from the Gulf of Oman through the Strait and up to Kuwait monitoring IRGCN operations, but there’d been no reports of anything unusual. But then at around 2100 I get an “urgent,” and so I head to the vault for a call with an analyst from NAVCENT. Turns out a Strikepod patrolling off the east coast of the UAE had phoned in four contacts around 0530 local, about half an hour prior to the attacks. It was active sonar, so the hits were reasonably solid, moving west/northwest at around six knots until they disappeared approximately seven miles off Fujairah. Falken [the Atom/Esquire integrated AI] had classified them as probable biologics – dugongs, these manatee-like things common in those waters. The AI was learning fast, but was still prone to misclassification about 20 percent of the time, so this analyst, she took it upon herself to double-check its work, and proceeds to make a pretty compelling case against dugongs, but stopped short of calling them torpedoes. They were too slow and quiet.

Was that the first indication that you might be dealing with something new?

That, and given that in the days leading up to the attacks a Virginia had phoned in intermittent contact with a Kilo operating about 20 nautical miles to the southeast. Yes, you could say my hackle was up. It was definitely the first indication that we might be dealing with something other than fast boats and limpet mines. And it was enough to convince CENTCOM that we should probably take a closer look.

Within twelve hours we carved out two six-ship Strikepods and sent them into the blast zones, and it wasn’t long before we had some hits. Side scanning sonar identified one large debris field to the east of Fujairah where Al Mazrzoqah, A. Michel, and Andrea Victory had been anchored, and a smaller one to the northeast where the Amjad was hit. Follow-up hi-def footage captured several irregularly shaped, metallic objects scattered along the seabed, but we needed to be absolutely sure. So, we got on the phone with COMSUBPAC, and about four days later, Jimmy Carter rolls in for Retract Stripe.

Were you directly involved in Operation Retract Stripe?

With PODCOM providing ISR and ESM support – yes, I was involved. And then once the recovery phase was underway I got called to the vault and was able to watch in real-time via [Strikepod] Relay as Carter’s ROVs recovered the debris and brought it aboard.

And what did it reveal?

For the most part the debris was unrecognizable – just twisted and mangled chunks of metal. But two large pieces were still intact – what looked like the stern section of a torpedo, and a nose section that contained an acoustic sensor of some kind, possibly from a Valfajr or EM-52.

What was your reaction?

I was impressed, to be sure, but hardly surprised. The Iranians had proven themselves quite resourceful with unmanned systems. They’re cheap, expendable, effective, and provide the plausible deniability they want. That is, unless the debris is successfully recovered, and the vehicle is constructed from something easily identifiable and already in the inventory.

So you were confident then that it was an Azhdar?

Confidence was high, but we weren’t one hundred-percent certain. There was also the possibility, however remote, that we were looking at actual e-Ghavasis, that the IRGCN had actually used the vehicles for their intended purpose – to insert special forces who then attached limpet mines to the tankers. Maybe they’d run into trouble and for whatever reason decided to scuttle them? But within hours a thorough analysis of the debris uncovered evidence of guidance systems, sensors, and processors, so between that, the nature of the blast damage, as well as the intelligence we’d been receiving, it all fell into place, and we concluded that Azhdars had been used in the Fujairah attacks.

Armed now with that information, were there any discussions in Washington of going public with it? To build a diplomatic case against Tehran?

I wasn’t really privy to the policy considerations, but if you start talking about a rogue state introducing what is essentially a stealthy, mobile, semi-autonomous mine into one of the most hotly contested bodies of water in the world – well it isn’t too hard to imagine our Gulf allies wanting to avoid the destabilizing effect that such a revelation might have, one that could easily mushroom into a full-blown regional crisis. And sure enough, it wasn’t long before official word came down from Dubai: the attacks were carried out by an unnamed state actor using divers attaching limpet mines. There was no finger pointing at Iran, and there was no mention of a weaponized UUV.

What about the report issued by the Norwegian Shipowners’ Mutual War Risks Insurance Association – the DNK? They concluded that it was in fact an Iranian “undersea drone” that had been used in the attacks. How did they know?

I’m not sure they actually did know. I have no idea what information they had, or where they got it, but it seemed more like speculation, or an analytic leap of faith. It did get picked up by Reuters, but the story fizzled pretty quickly, and pretty soon it faded from the news cycle entirely.

Meanwhile your job had become more urgent?

Iran had just upped the gray zone ante, so yes, very much so. Having confirmed that Iran was in possession of an operational, weaponized UUV, it was critical that we find out as much as we could – its true capabilities, warhead yield, current inventory, production rate. And from there, anticipate how it might be employed in the future.

Let’s fast forward a bit. There’s a lull in activity as the world, particularly Iran, grapples with COVID-19. Then things start heating up again in early 2021.

The sanctions put in place by the Trump administration were taking a real, measurable toll on everyday Iranians. And after Soleimani, and the struggles with COVID-19 – which apparently was “engineered” by the United States using Iranian DNA – there was mounting pressure on [Iranian President Hassan] Rouhani to stand up to Washington. Closing the Strait [of Hormuz] had always been viewed as the nuclear option, but conditions were quickly reaching a point where such a move might be seen as the only recourse.

So, in late 2020 and early 2021, the attacks on Gulf shipping resumed in force, and well beyond the pinprick operations of the recent past. A broader campaign appeared to be underway, with several tankers attacked every week, some with limpet mines, a handful seized by special forces, but most seemed to be the result of conventional mines, which was all at once frustrating and puzzling. Fifth Fleet under Operation Sentinel had been working overtime providing escorts and minesweepers, and we’d been providing Strikepods for MCM since the beginning of Indigo Cloak. There was no surface activity indicating that an IRGCN minelaying operation was underway. We were taking a lot of heat at PODCOM, but everything checked out – technologically, operationally.

You believed it was something else?

Our intelligence on the e-Ghavasi SDV suggested that it was only capable of around 6 knots, or less when loaded down with a warhead. With the convoys running at anywhere from 15 to 20 knots, we expected that, should Tehran ever make good on its threat, the Strait would be seeded with conventional mines – anything from floating and moored, to EM-52s and MDM-3s – with any Azhdar attacks reserved for targets at anchor, like Fujairah, or while entering or leaving port. So we concentrated Remora-heavy Strikepods in those areas and prepared for CUUV [Counter-UUV] operations, but when the convoys were being hit after months of persistent, intensive minesweeping, and without any acoustic evidence indicating torpedoes or rising mines, it suggested – at least to me – that something else was at play, that Iranian engineers had found a way to boost the Azhdar’s power output, enabling it to track and strike targets traveling at cruising speed.

An improved Azhdar? In eighteen months?

Yes. And not only in terms of power and propulsion. We later learned that after the success of the Fujairah operation, the Azhdar benefitted from the Valfajr and Hoot torpedo programs. It had clearly become a priority for Tehran.

How was the IRGCN deploying them?

That was the million-dollar question, one that was the cause of many a sleepless night. We had a lot of information from disparate sources, but we needed to connect the dots.

We knew that the Fujairah Azdhars were based on an e-Ghavasi, which was compatible with a standard 21 inch (533 mm) torpedo tube, and we also had intelligence that the vehicle’s control surfaces were designed to recess into the hull and spring open upon launch. This suggested that the Azhdar was intended to be deployed from a submarine for maximum stealth, which could have meant any one of four different classes, but most likely Kilo or Ghadir. IRIN Kilos, when they were actually working, typically operated in the deeper waters of the Gulf of Oman, and so a Kilo was likely the platform of choice for the Fujairah attacks. But they could also have conceivably been launched over the side of a ship, or even from the side of a pier.

We also knew that Ghadir operations had undergone a pretty fundamental shift in recent months. The Ghadir is a midget sub, with a range of only about 500 nautical miles surfaced, and about 50 submerged, so typically their deployments were quick, out-and-back junkets that only lasted a few days. But in late 2020, we began to notice that they were gradually increasing in duration. A week, then a few weeks or more. And they were random and staggered, seemingly without rhyme or reason. You might have four boats sail, with three of them returning a few days later, two of which would then sail again within hours of tying up and then be gone for like two weeks. The OPTEMPO was all over the place, and in hindsight it was clearly an attempt to confuse and deceive us, because pretty soon three quarters of the Ghadir fleet – ten boats – were on seemingly extended deployment.

But what finally sealed it was the uptick in IRGCN night-time surface operations. We thought they were exercises, and of course we had Strikepods and Esquires keeping a close watch. And one night, there it was – in the moonlight, a Gasthi [fast boat] moored alongside the unmistakable silhouette of a conning tower.

They were rendezvousing with the subs?

Yes, ma’am.

From the outset of Indigo Cloak we’d had Strikepods positioned outside Bandar Abbas, Qeshm Island, and Jask, keeping tabs of the Ghadirs, and since there were only a handful deployed at any given time, we could usually provide man-to-man coverage. But we failed to anticipate a slow-motion surge, so we had to scramble and switch to zone, and inevitably they’d slip through and disappear. They’d sprint and drift, and – unbeknownst to us at the time – settle on the bottom, somewhere in the shallows flanking the shipping lanes.

Operating on minimum power, the Ghadirs could lie there on the seabed for days, waiting patiently until targets appeared overhead and then quietly release their Azhdars. At a prearranged time and place, they’d head to the surface, rendezvous with a reload crew, snorkel while taking on food and ordnance, and perhaps there would be a change in personnel. Then they’d head back to the bottom to await more prey. In this way the Ghadirs could remain on station almost indefinitely, like stealthy, semi-permanent undersea missile batteries.

The Navy had actually anticipated something like this. We’d gamed it several times, but always with the expectation that they’d be shooting torpedoes – essentially martyrdom operations, since we’d follow the acoustic trail right back to their front door. But releasing an Azhdar generated very little sound, and what little there was would be masked by the ambient noise. The Ghadirs were already quiet and hard to detect, but if they sat on the seabed, it would be virtually impossible to find them.

So, an organized Iranian anti-shipping campaign was underway. What was the reaction in Washington?

Oil prices were skyrocketing. People were paying close to four dollars a gallon at the pump. Insurers were running scared, and shipping traffic was slowing. We’d been here before, of course, in 1988, and also in 1984 in the Red Sea, but the economy always found a way to adjust to the risk. This time things seemed different, though, especially when the media got to publishing rumors of Iranian “killer robot submarines” roaming the Gulf.

The U.S. had to respond, but the question was how given the risk of escalation. Iran could answer with shore-based ASCMs, or even turn the Azhdars against U.S. warships, a particularly problematic scenario. There were also concerns that they would go scorched earth and order proxies to attack Saudi Arabia or Israel.

And to further complicate matters, this was the first national security test of a newly elected president who was bound and determined to demonstrate U.S. resolve.

Something had to be done. So the president tasks the Joint Chiefs, who then turn to WARCOM, and one day I get a call from Coronado pitching me on this crazy counter-gray zone operation to disrupt the Azhdar attacks.

Seizing the Ghadirs?

A daring plan, to be sure, but since PODCOM had some recent experience in this area, I was sure we could help pull it off.

And so Indigo Cloak becomes Indigo Spear.

Yes, a WARCOM/PODCOM joint operation, with Esquires and Strikepods providing support for what was essentially a large-scale, covert interdiction campaign. In a nutshell, teams of SEALs – Rapid Interdiction Platoon (RIPs) – would be assigned to three LPDs and three DDGs which would be fanned out along the shipping lanes, from the Strait to Farsi Island. PODCOM would be charged with hunting submarines, detecting and tracking replenishment operations, and pinning down the boats until the RIPs arrived to grab them.

Can you explain a typical Indigo Spear operation?

The Ghadirs were careful to stay within Iranian territorial waters. Without a declaration of war, this made Esquire and RIP ops tricky, so they would occur only under cover of darkness. Strikepods, of course, had been operating well inside twelve miles for months.

The first task was finding the subs, and we had two methods of doing that. First, through a kind of large scale MCM operation, we deployed Strikepods fitted with ultra high resolution side scanning sonar to comb the seabed. If they found something interesting, they’d establish a kill box by forming a wide-area passive sonar array to listen for transients, or a torpedo door opening. If an Azhdar was detected, the Strikepod would vector a Remora, and on at least three occasions we achieved good kills and traced it back to the source.

The second method was by monitoring the replenishment tenders operating out of Bandar Abbas and Qeshm Island. An IRGCN replenishment team would head out between 0100 and 0300 local, usually in two Gasthis with a crew of three – one pilot, and two divers – with each towing an Azhdar behind. For EMCON purposes, the rendezvous would have been arranged prior to deployment, or during the previous replenishment evolution, and at the predetermined time, the Ghadir would come to periscope depth, take a peek, surface, and connect with the tender.

The actual reload operation would be fairly straightforward. The Gasthis would maneuver alongside the Ghadir and deploy their divers, who would then submerge the Azhdars and guide them into the empty torpedo tubes. Meanwhile, the sub would snorkel, take on food and supplies, and occasionally there’d be a change of personnel. And then back down it would go. The whole process would take less than thirty minutes.

So, our job was to detect the Gasthis as they left port, and if something looked interesting, we’d order the closest Esquire to launch a Sybil [quadrotor UAV] and we’d be eyes-on with infrared video in a matter of moments. We’d watch the evolution, and as they headed back to port, we’d vector a nearby Strikepod, or deploy one from the Esquire to mark it. Meanwhile, the Sybil would have alerted the task force and a RIP would be deployed.

And what then?

The Strikepod would have the sub pinned down with active sonar, so they’d know we had a fix. We knew from the Fujairah debris that the Azhdar was equipped with an undersea modem, and intelligence suggested that the Ghadirs were similarly equipped, so the RIP would send them a few chirps via DUMO [Dipping Undersea Modem] ordering them to surface. There’d be no response, of course, so we’d raise our voice and start detonating Remoras, one every minute or so. Nothing to cause any damage, but enough to get their attention, and by the third or fourth one we’d usually hear them blowing ballast. The Iranians were aware of our ROE, and so could be reasonably sure we wouldn’t attack unless provoked. Nevertheless, even for the most confident sailor, there are few things more terrifying than being depth charged, and eventually the fear and uncertainty won out and they’d head for the surface where our guys would be waiting. They’d offload the crew and the weapons, and then use the combined thousand-plus horsepower of their two RHIBs to drag the boat out to a waiting LPD where it would be maneuvered into the well deck for … safe keeping.

How were you able to sustain the operation for so long without alerting the Iranians?

When a sub surfaced, there was always an orbiting Sybil to jam any outbound traffic, and of course we took the crew into custody. But mostly it was just skilled exploitation of what theoretically should have been their strength – minimal C2. The Ghadirs were expected to maintain strict EMCON, coming shallow at a prearranged time and wait for a visual on the inbound tender. Since it was seven days between evolutions, it gave us a window to operate without raising suspicion. And when a sub was a no show, the tender assumed it was a miscue and headed home. But if a sub surfaced and the tender was a no-show, the skipper was expected to return to port.

So that’s how the Iranians caught on?

Exactly. When the subs were no-shows and weren’t eventually defaulting back to base, they realized something was up. The night-time excursions came to an immediate halt, and the Iranians were so desperate to avoid additional losses they cobbled together a flotilla of Boghammars equipped with DUMOs to fan out and broadcast a kind of acoustic kill switch ordering the remaining Ghadirs home. Our rules of engagement were quite clear, and unless fired upon, we could not engage, so we could only watch and liste as they headed home to fight another day.

How many Ghadirs made it back?

Of the ten boats deployed, a total of four made it home. So, with four in the bull pen, they walked away with eight.

And what was Tehran’s reaction?

Outrage. We were pirates, and the submarines were in territorial waters engaged in training exercises, and we’d engaged in an act of war. But their protests were fairly short-lived, since we now had Azhdars in our possession, as well as forensic evidence from numerous blast sights, and the testimony of several IRGCN sailors. Washington was able to skillfully control the narrative, and once the news media seized upon the Azhdar, Iran’s denials increasingly fell on deaf ears, while the United States was often praised for showing restraint in the face of what was a brazen provocation on the part of Iran.

Nevertheless, Tehran did manage to achieve some marginal gains.

They’d managed to sow plenty of instability, and inflict significant albeit largely short-term economic damage on the global economy, and left unchecked, the psychological effect of Azhdar operations alone could have effectively closed the Strait. So, from that perspective, Iran had asserted itself and demonstrated its power to influence events in the region. But they’d forfeited six submarines in the process, and largely obliterated any chance of consolidating power or strengthening their economic security.

Would you consider Indigo Spear a victory for the United States?

Yes and no. We’d helped avert a global economic meltdown, but ultimately it was yet another stalemate in what was an intractable regional quagmire. Yes, Iranian naval power had suffered a blow, but one from which they would quickly recover. On the plus side, we’d demonstrated our resolve, and our willingness to use force. We’d also proven, once again, that adversary gray zone tactics could be countered effectively by leveraging advanced unmanned systems. But nevertheless, one thing was pretty clear: if there was going to be stability in the Gulf region, it wasn’t going to happen by force. We couldn’t bend Iran to our will without a full-scale operation that destroyed their capability to wage war. And that wasn’t going to happen absent a truly compelling reason to risk so many lives.

Yet Tehran’s game of incremental belligerence, of gray zone brinkmanship, was becoming increasingly untenable. And in the absence of strategic clarity or competent statecraft on either side, Tehran and Washington were fumbling their way toward yet another protracted regional war that neither could afford to lose.

[End Part IV]

David R. Strachan is a naval analyst and writer focusing on autonomous undersea conflict. He can be reached at david.strachan@strikepod.com.

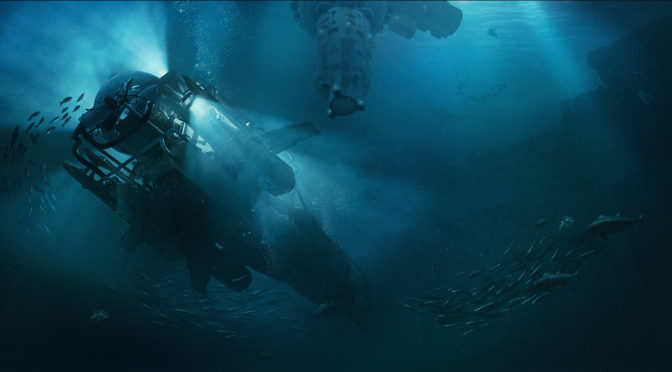

Featured Image: “Keyframe 2: The Descent” by Robin Thomasson via Artstation