Chokepoints and Littorals Topic Week

By Captain Jamie McGrath, USN (ret.)

Keys to the World

Naval theorist Milan Vego opens a chapter on chokepoint control with a quote from British Admiral Sir John Fisher, who stated that there are “five keys to the world. The Strait of Dover, the Straits of Gibraltar, the Suez Canal, the Straits of Malacca, and the Cape of Good Hope. And every one one of these keys we hold.”1 Fisher spoke from an Anglo-centric view, but his point is evident that control of key chokepoints equated to control of national strategic interests. But a century later, with the technological advances in weapons and sensors, and the interconnectedness of the global economy, can such a claim be made today?

There are over 100 straits where international interest in the free flow of trade transcends the interests of the nearby littoral states. Not all of these maritime chokepoints are of equal importance. Military strategists often speak as Fisher did of strategic chokepoints, believing them to have significant geopolitical value and act as epicenters for maritime strategy, where the control of which is considered vital for success in maritime conflict. But are these chokepoints truly strategic? Does the success of a nation’s maritime strategy actually hinge on the control or loss of control of these narrow seas?

Perhaps the strategic value of any given chokepoint is overstated because the ability to truly “control” these chokepoints is significantly degraded in the current maritime threat environment. The focus should instead be placed on strategic seas, and not the connectors between them.

Strategic Versus Operational Significance

Before scuttling the idea of strategic straits, there should be a common understanding of the difference between the strategic and operational importance of maritime geography. Maritime strategy is the science and art of using all naval and non-naval sources of power at sea in support of the national military strategy, with military strategy being “the art and science of using or threatening to use military power to accomplish the political interests of a nation…”2 The 2018 National Defense Strategy calls for:

“A more lethal, resilient, and rapidly innovating Joint Force, combined with a robust constellation of allies and partners, will sustain American influence and ensure favorable balances of power that safeguard the free and open international order. Collectively, our force posture, alliance, and partnership architecture, and Department modernization will provide the capabilities and agility required to prevail in conflict and preserve peace through strength.”3

The focus on lethality, resilience, and lethality within an alliance and partnership architecture, combined with “lethal, agile, and resilient force posture and employment,”4 and “a global strategic environment [which] demands increased strategic flexibility and freedom of action,”5 indicate that fixed geographic positions like chokepoints have reduced strategic relevance in U.S. strategy.

Naval operations are defined as the “theory and practice of planning, preparing, and executing major naval operations aimed at accomplishing operational objectives.”6 While operational objectives are chosen to achieve strategic ends, there often are multiple operational options to a support strategy. The operational value of a chokepoint tends to be temporal and depends on the other operational factors of time, space, and force of the particular operation. A chokepoint with high operational value may have limited or no strategic value if other options exist to achieve the national political objectives.

Traditional Methods of Sea Control

The control of chokepoints has long been a primary way to control access to a given body of water. Revisiting Fisher’s assertion that there were five keys to the world, control of key straits meant control of the flow of global maritime traffic and, therefore, the strategic interest of most maritime nations. Warships and merchantmen during the age of sail depended on the prevailing winds for reliable propulsion and shore bases for routine resupply. These trade winds and shore bases funneled ships through specific shipping lanes, many of which transited the key chokepoints Fisher identified. Since transit of these chokepoints was essential, controlling them guaranteed control of merchant shipping and warship movement.

The emergence of steam propulsion removed reliance on the trade winds, but increased dependence on the shore bases that had been established in the age of sail, which were starting to serve as coaling stations. Thus, in Admiral Fisher’s time, his assertion was correct. But since World War II, dependence on shore basing for resupply has diminished. The U.S. Navy perfected at-sea replenishment during World War II, and merchantmen have significantly increased their unrefueled range, both of which reduced the reliance on shore stations and subsequent dependence on specific shipping lanes.

Chokepoints simplify several operational and tactical aspects of naval warfare by concentrating forces. This, in turn, limits the challenges of scouting and screening, because less sea space must be scouted and screened. The avenues of approach to the chokepoint are limited, so the party that controls the chokepoint can concentrate forces or make better use of limited forces available.

Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō’s defeat of Russia’s Second Pacific Squadron at the Tsushima Strait demonstrates how chokepoints simplify scouting. Togo did not know when the Russian fleet would arrive, nor did he wish to search for it in the open ocean. But he did know that the Russian fleet had to pass through the Tsushima Strait to reach its base at Vladivostok. This allowed Togo to concentrate his scouting force of cruisers in the strait and consolidate his battle line inside the Sea of Japan. But what if the Russians had entered the Sea of Japan through the La Pérouse Strait, Tsugaru Strait, or Strait of Tartary? In the 1890s, the limitations of coal-fired steam plants meant that traveling the extra 1000 or more miles without a coaling station made the Tsushima Strait the only choice. Today, however, at-sea logistics provide naval forces greater flexibility in entering strategic seas.

Changing Military Value of Chokepoints

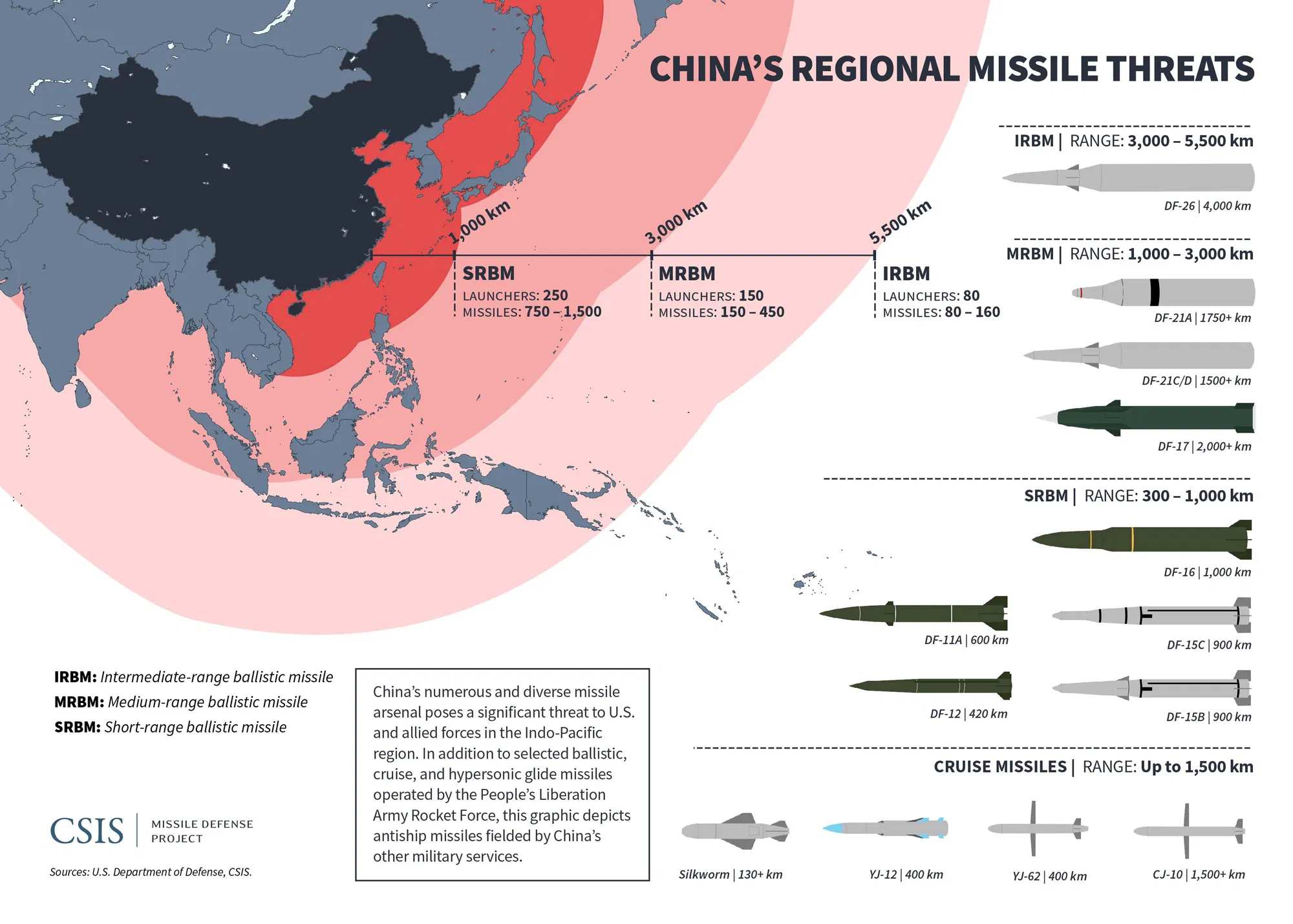

Historically, chokepoints held strategic military value partly because they forced ships to transit within range of the weapons and sensors posted there, and made movements more predictable. Into the second decade of the twentieth century, optical sensors and coastal guns limited that range to or just beyond the horizon. Technological advances over the intervening century expanded that range immensely. First, aircraft extended scouting range, then, as aircraft improved, expanded the striking range of weapons well beyond the chokepoint’s horizon. The introduction of radar further enhanced scouting and early-warning capabilities, and space-based surveillance now allows for the searching of vast ocean areas independent of geographic chokepoints. The missile age added over-the-horizon, ship-killing weapons, with anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBM) marking the ultimate long-range strike capability.

Holding a chokepoint serves two fundamental purposes, one rooted in sea control and the other in sea denial. The sea denial case, often a strategy of the weaker navy, holds that by controlling the chokepoint, an adversary cannot access the seas on its opposite side. As Vego points out, this is often part of a larger, major defensive joint/combined operation and maybe one of several elements of a national defensive strategy to either bottle up an opponent’s naval force in its own narrow seas, or prevent an opponent’s naval force from entering a narrow sea where it could threaten the defending nation’s territory.7 In the sea control case, control of the chokepoint theoretically allows one to use their naval forces at the time and manner of their choosing within the chokepoint and in the seas controlled by the strait. That is to say, if a nation controls a chokepoint, naval forces and maritime trade can pass through that chokepoint freely at the discretion of the nation that controls it.8

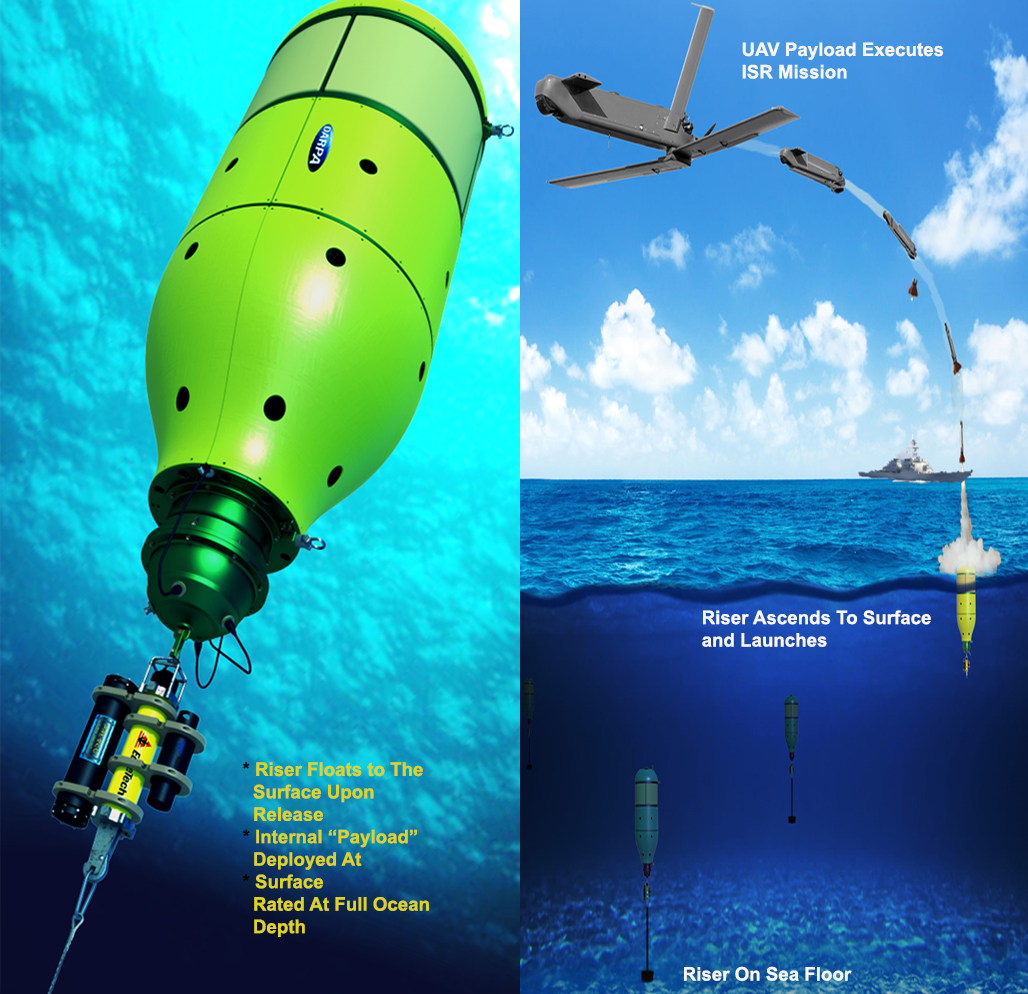

In the current maritime threat environment, controlling the land and water in the vicinity of the chokepoint no longer represents the exclusive manner to control it. The focus on strategic chokepoints may have held when the range of weapons was barely over the horizon, but today an adversary no longer has to control the geographic entrance to strategically important seas to deny their use. Space-based sensors and long-range missile firepower allow an adversary to effectively close, or at least threaten closure of, geographic chokepoints without the traditional need to hold the immediate surrounding land or seas. “Holding” a geographic chokepoint no longer guarantees the use of the seas on either side, nor does it ensure safe passage through the chokepoint itself. Therefore, the U.S. Navy would be better served to focus more broadly on its ability to control or deny strategic seas than the strategic chokepoints of ages past.

Changing Economic Value of Chokepoints

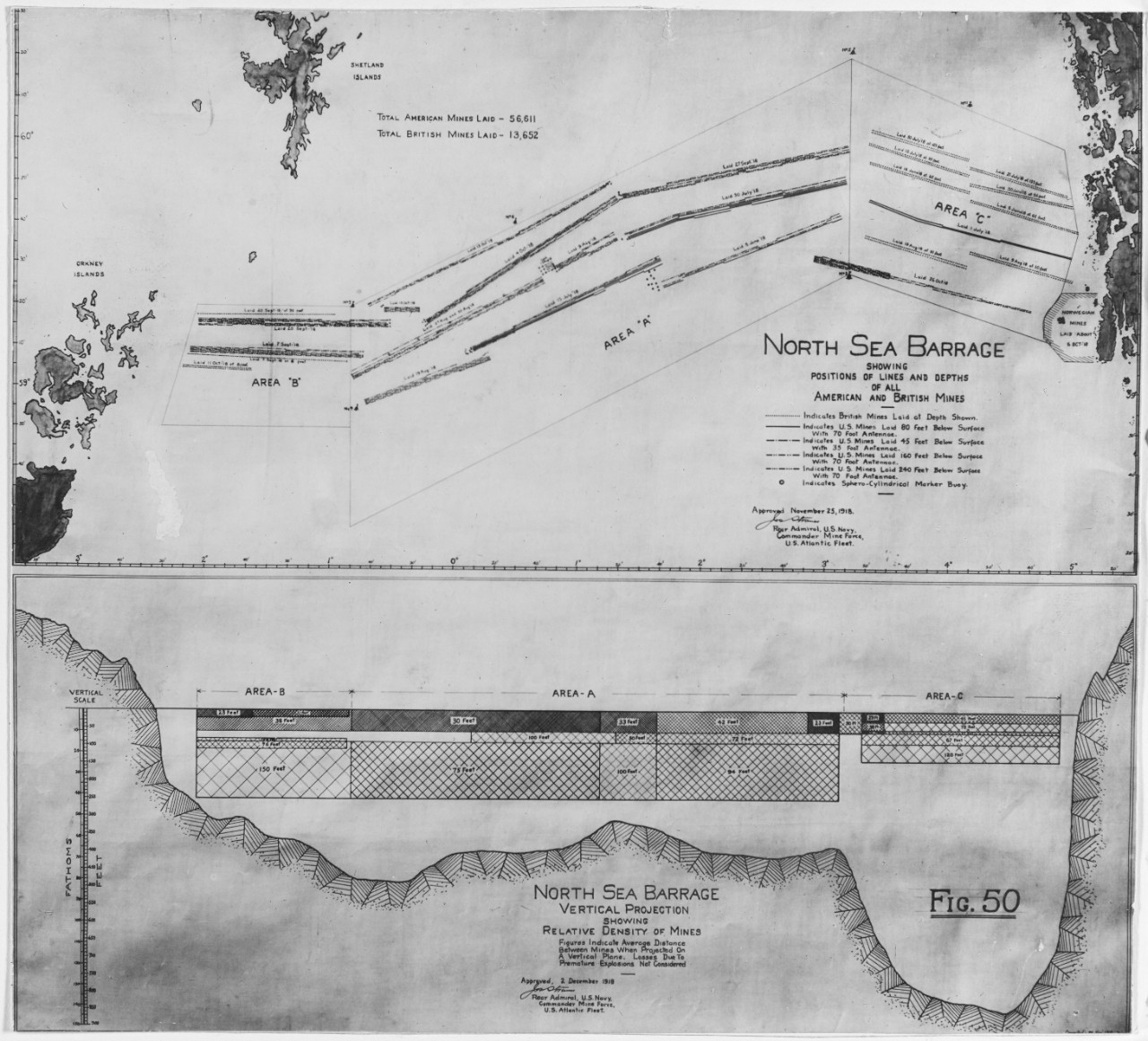

Another element that gives a chokepoint strategic value is the volume of trade transiting the strait. Traditionally, blockades and maritime trade warfare have used control of chokepoints to great strategic effect. Britain’s control of the Dover Straits, combined with the North Sea Mine Barrage, closed all maritime trade to Germany during World War I and contributed to the fall of the Kaiser’s government in 1918. During World War II, the failure of the Axis powers to seize the Suez allowed Great Britain to continue using the canal for resupply of its empire. Would such action have the same strategic effects today?

Today, high trade volume certainly gives a strait economic value because these chokepoints often represent the shortest route from manufacturer to market and thus the cheapest transportation cost. But is controlling trade through a strait a viable strategic goal? Chris McMahon argues that maritime trade warfare is ineffective in today’s global economy. Among the many reasons he presents, he notes that the closing of chokepoints has no real impact on global trade.9 One of the most-often mentioned strategic chokepoints is the Strait of Malacca because it handles so much of the world’s maritime traffic. But how would closing the Strait of Malacca affect global trade? It would impact Singapore’s role in the global shipping market, certainly. But would the global shipping network be severely burdened by having to transit the Sunda Strait or the Lombok Strait? Would there be a cost increase, yes, but once the market adjusts for the increased cost, shipping will find a way to make it work.

Consider the wave of piracy off the Horn of Africa in the early 2000s, an area often discussed as a strategic chokepoint because of the volume of trade passing through the Arabian Sea. Shipping companies dealt with the insecurity of that maritime region in one of three ways – accept the risk and charge accordingly, arm themselves against pirates, or re-route ships around the Cape of Good Hope at increased cost and charge accordingly. In each case, maritime trade continued. Lord Fisher mentioned the Suez Canal as one of the keys to the world, but it has been closed on five occasions since it opened in 1869, including for eight years between 1967 and 1975. During that most recent closure, the cost of shipping around the Cape of Good Hope was markedly higher than the Suez route but presented no serious economic hardship to global consumers. Rerouting Pacific trade for a closed Strait of Malacca would have a similar minimal effect on the cost of global trade.10

Chokepoints Can Be Superseded

The demise of the strategic value of chokepoints is revealed by looking at some traditional strategic chokepoints of the past. One of Fisher’s keys to the world, British control of the Straits of Dover, seemingly kept Hilter’s Kriegsmarine bottled-up in the North Sea, much as it had the Kaiserliche Marine three decades before. But Germany negated the British advantage by conquering France and establishing bases in Brittany, unfettered by the Straits of Dover. To be sure, the straits still impeded access to merchant shipping and warship transit to the German homeland, but control of the strategic strait did not mean control of the German U-boats. Chokepoints can be bypassed.

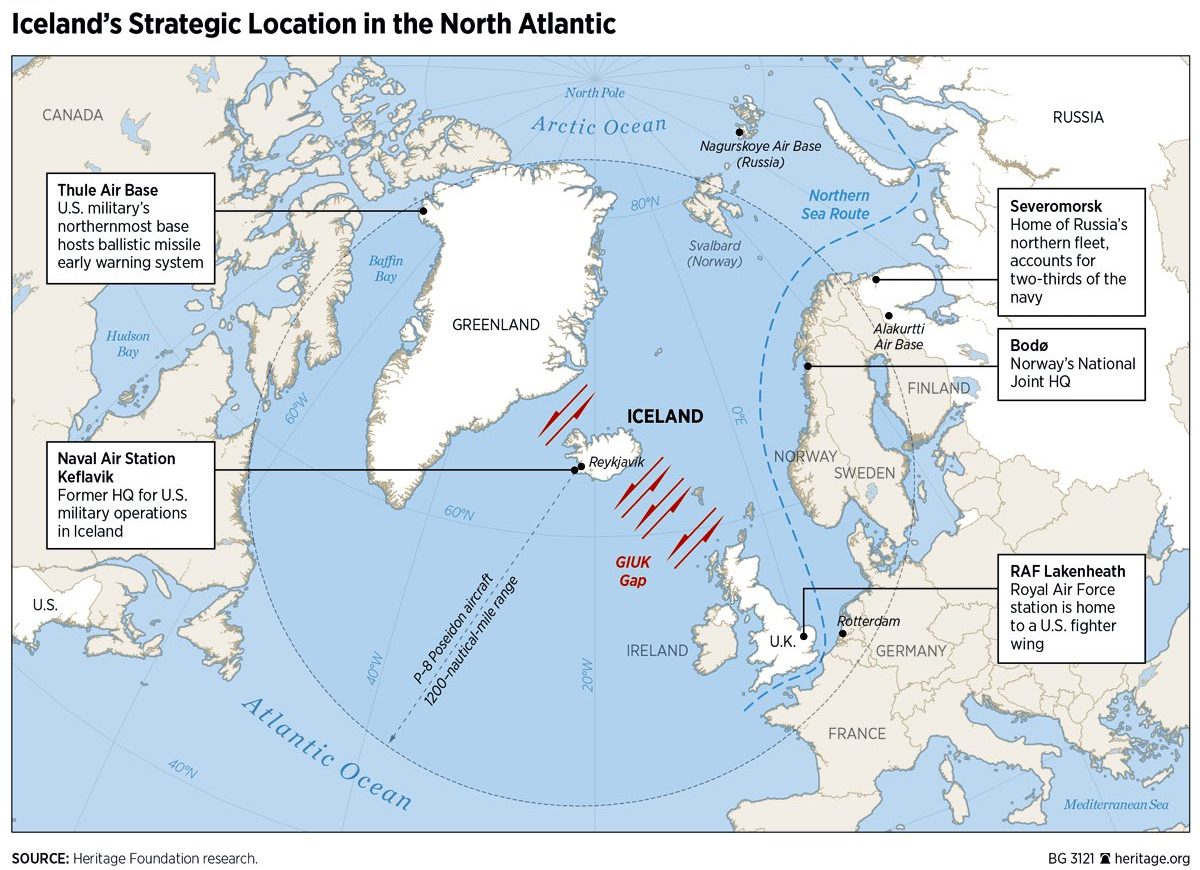

During the Cold War, the water between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom – the so-called GIUK Gap – was a strategic chokepoint because Soviet ballistic-missile submarines had to pass through that gap to threaten the United States. The later development of longer-range submarine-launched ballistic missiles meant the submarines could remain in the Arctic to launch these weapons, thus limiting the strategic value of the GIUK Gap as a chokepoint. Chokepoints can be outranged.

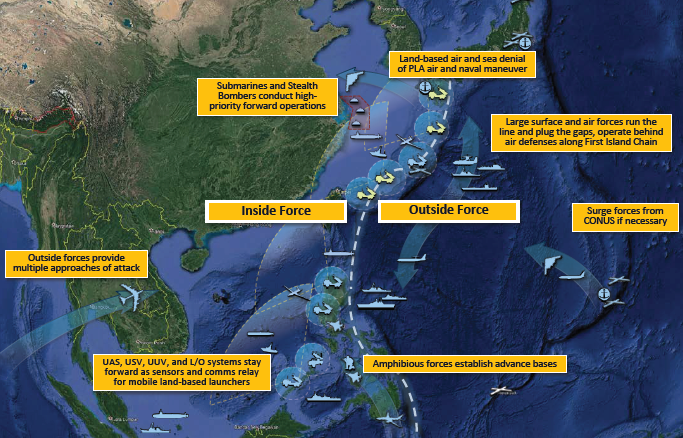

Today, a resurgent China lays claim to the South China Sea (SCS) as its own internal waters. As discussed above, the Strait of Malacca has traditionally been a key to control of the SCS and, therefore, strategically important for trade between Europe and Asia. But the Strait of Malacca is not the only access route to the SCS, which can also be accessed through the much larger Luzon Strait and numerous passages through the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagos. The PRC recognizes this and has adopted control mechanisms that do not depend on control of the chokepoints, but instead focuses on long-range anti-access, area-denial (A2/AD) weapons and redundant fortified islands within the SCS.11

China’s A2/AD strategy in the SCS is important for two reasons. First, the assumption that physical control of a chokepoint guarantees use of the chokepoint is invalid in the face of PRC A2/AD weapons and sensors. Although the United States and its partner states may possess the land on either side of the Strait of Malacca, and have sufficient naval forces to patrol the strait, the PRC could nonetheless prevent free transit of the Strait of Malacca using ASBM and long-range anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM). Furthermore, these long-range weapons based on the Chinese mainland or in the central SCS can contest the other straits leading into the SCS. Conversely, the reduced reliance of predictable trade routes for maritime traffic – both merchant and military – means they can easily bypass the Strait of Malacca if it were to be “controlled” by an opposing power.12 Chokepoints can be replaced.

Conclusion

The question then should not be “what are today’s strategic chokepoints?” but instead, “what are today’s strategic seas?” Control of chokepoints is only one of the ways to control a sea. Vego writes that there are two primary arenas of naval conflict: open ocean and narrow seas. While many characteristics differentiate the open ocean from the narrow sea, the predominant one is proximity to land.13 In narrow seas, the land influences many aspects of naval warfare, from the ability of naval vessels to maneuver to the threat from land-based weapons. As one moves further out to sea, maneuver space opens up and land-based threats dissipate, or so it would stand to reason.

The ability of naval forces to operate freely on the open ocean outside the threat of land-based weapons, whether missiles or aircraft, is greatly diminishing in the current threat environment. This, in turn, means an expansion of the areas previously considered narrow seas – even if not in all aspects. If the narrow seas have now broadened to cover a much higher portion of the world’s oceans, then the restrictive chokepoints once seen as strategic lose much of their relevance.

There may be operationally compelling reasons to control a chokepoint, but their strategic value is greatly diminished in an era of space-based sensors and proliferating long-range missiles. Control of a chokepoint no longer means the “keys to the world” as it did in Admiral Fisher’s day. Expending the time and force to control a chokepoint will likely not result in the strategic advantage sought, and worse, could fix forces to a geographic location when mobility is operationally necessary. The U.S. would be better served exercising more agile and dynamic mechanisms of strategic sea control and sea denial rather than focusing on the obsolete idea of strategic chokepoints.

Captain Jamie McGrath (ret.), retired from the U.S. Navy after 29 years as a nuclear-trained surface warfare officer. He now serves as a Deputy Commandant of Cadets at Virginia Tech and as an adjunct professor in the U.S. Naval War College’s College of Distance Education. Passionate about using history to inform today, his area of focus is U.S. naval history, 1919 to 1945, with emphasis on the interwar period. He holds a Bachelor’s in History from Virginia Tech, a Master’s in National Security and Strategic Studies from the U.S. Naval War College, and a Master’s in Military History from Norwich University.

References

1. Quoted in Milan Vego, Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice (Rutledge: London, 2016), 188.

2. Milan Vego, Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice (Rutledge: London, 2016), 2.

3. James Mattis, Summary of the 2018 National Military Strategy of the United States of America (US Department of Defense: Washington, DC, 2018), 1.

4. Ibid., 7.

5. Ibid.

6. Milan Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea: Theory and Practice (Rutledge: London, 2017), 1.

7. Vego, Sea Denial, 301.

8. Vego, Sea Control, 188-9.

9. Christopher J. McMahon, “Maritime Trade Warfare,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 70: No. 3 (Summer 2017), 29-34.

10. Ibid., 29-30.

11. Naval War College Professor James Holmes argues that considering PRC sea power, their entire military must be considered and not just the PLAN, see James Holmes, “Visualize Chinese Sea Power,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings (June 2018). https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018/june/visualize-chinese-sea-power

12. McMahon, “Maritime Trade Warfare,” 29-30.

13. Vego, Sea Control, 18-20.

Featured Image: August 6, 1988, Egypt: An aerial port bow view of the aircraft carrier USS FORRESTAL (CV 59) transiting the Suez canal. A formation of crewmen spells out”108″on the bow to signify that the ship has been at sea for 108 consecutive days. (Photo by PH2 Buckner, USN/U.S. National Archives)