The following is part of Dead Ends Week at CIMSEC, where we pick apart past experiments and initiatives in the hopes of learning something from those that just didn’t quite pan out. See the rest of the posts here.

Despite (or possibly, because of) Washington Naval Treaty cutbacks in the 20s and the Depression-induced budget troubles in the 30s, the U.S. Navy experienced quite a period of experimentation during the interwar decades. Without a doubt, the most glamorous example was the airship program, which featured yet another ship called Shenandoah, and culminated in the rigid airships USS Akron and USS Macon (ZRS-4 and ZRS-5).

But we are not here to talk about those, strictly speaking – we’re here to discuss their parasites. Parasite aircraft, that is. Akron and Macon were flying aircraft carriers, each carrying three or four scout aircraft to serve as the long-range eyes of the fleet below.

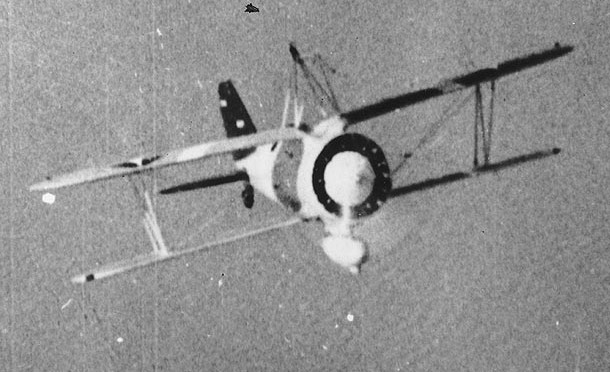

The Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk originated in a 1930 Navy requirement for a small carrier-based fighter. It ended up not performing too well in that role, but was retained in service as the only aircraft small enough to fit through the hanger doors of Akron, then under construction.

Here’s the dead end – the truly daring, truly paradigm-shifting dead end. How many planes have you ridden in that possessed some form of landing gear? I trust that it was every single one. So what do you do with a plane that takes off and “lands” via a hook above the fuselage? If you’re the Navy in the 1930s, you ditch the landing gear. No fixed gear, no retractable gear – simply no wheels at all. The Goodyear company would have been very fearful at the lost business, if they weren’t also the ones building the giant ships carrying the tire-less biplanes. All in all, probably a good deal for them.

But aircraft that never kissed ground were not long for this Earth. The Navy’s lighter-than-air fleet followed the general trend of rigid airships, in which they died violent deaths. Akron went down in a storm in the Atlantic (killing Rear Admiral William A. Moffett) in 1933, and Macon went down in the Pacific while operating out of Moffett Field just two years later. Sparrowhawks lost their niche and paradigms were brought back to normal.

Still, it is worth pondering the lesson of the Sparrowhawk. It took something that every single aircraft must have in some form or another, and just did away with it when the need disappeared. It didn’t end up working out – but it deserves to be admired.

Matt McLaughlin is a Navy Reserve lieutenant who doesn’t usually discuss parasites as frankly as he does here. His opinions do not represent the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense or his employer.